Thesis Hum 2020 Abrahams Ayesha.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutton Or Chicken Akhni

MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI In a pot braise a large onion with oil (if using mutton) if chicken little oil n ghee till pale pink. Add in 1 teaspoon whole jeera seeds 4 whole black peppercorns 4 whole elachi pods 3 pieces cinnamon sticks 4 whole cloves 3 sliced green chillies Braise till golden brown. Then add in your meat or chicken. Add: 1 tablespoon of ginger and garlic paste 1 ½ teaspoon salt ±1 ½ teaspoon turmeric 1 teaspoon of red chilies paste STIR WELL Braise for a few minutes. Add some water and let cook till meat is tender. When meat is tender and water is almost dry add the other masalas: ± 2 tablespoons chili powder 2 teaspoons dhana /jeero powder 1 teaspoon crushed chillie powder some peas Braise nicely for few minutes then add in 1 grated tomato. Cook a few minutes. add 2 tbsp plain yogurt Add 6 cups boiling water and add in potatoes about 5 cut in pieces. Let boil for a few min so potatoes start getting soft. Lower heat a bit. Add 3 cups pre soaked basmati rice and add to pot. Add some salt for taste. Add in some chopped dhania and mint and about half teaspoon garam masala powder. Let boil for a few minutes till rice starts cooking. Stir also so well so that rice doesn’t stick to the bottom. When rice is boiling nicely and water is almost drying but there must be some water then put in oven and steam for about 30 to 40 minutes at 180°C. -

Restaurant Menu

Authentic Indian Cuisine STARTERS - MIXED STARTERS - SEAFOOD Mixed Kebab ......................................... £4.95 Prawn Cocktail ..................................... £3.95 Vegetable Platter (for two) ........................ £7.95 Prawn Puree .......................................... £4.95 Tikka Platter (for two) ............................... £8.95 Deep fried unleavened bread with prawn stuffing Sword Fish Tikka ................................... £5.95 STARTERS - VEGETABLE Stuffed Prawn Pepper ........................... £5.95 Onion Bhaji Deep fried spiced onion cutlets ......... £3.50 King Prawn Puree .................................. £5.95 Vegetable Samosa Deep fried pasties ........... £3.50 Deep fried unleavened bread with king prawn stuffing Aloo Chat Pieces of potato cooked in sour sauce ..... £3.50 King Prawn Garlic ................................. £5.95 Chilli Mushrooms .................................. £3.50 King prawn in garlic and butter Garlic Mushrooms ................................ £3.50 King Prawn Butterfly ............................. £5.95 Paneer Tikka ......................................... £3.75 King Prawns Shashlick BAZZAR special........ £5.95 Indian cheese marinated with spices and herbs Chana Paneer ........................................ £4.50 TANDOORI SPECIALITIES Channa puree ........................................ £4.50 These dishes are marinated with spices and then grilled in a special tandoor and served with salad Paneer Shashlick .................................. £4.50 Indian cheese -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

An Historical Analysis of Awankaru Sounds with a New'perspective

An historical analysis of Awankaru Sounds with a new'perspective Thorough investigation into Indo-Aryan, Arabic-Persian and European elements. New theories, bold assertions, interesting suggestions. + H/1RDEV BAHRI Publishers BHARA*IS?RESS PRAKASHAN, DARBHANOA ROAD, ALLAHABAD—2. B^ffg |MM } (INDIA). $ ol e^ Distributors ¥ lLOKBHAifATif 15A—Mahatma Gandhi | margj I'MM 1_ J I Allahabad—1 Rsl^O. Prof Dr. H Pri D"^namSrnghSbab V.G *05. Sector 16 SikhiscD t-'tattdi<tarh \ ] la! [With special reference to Awankari] HARDEV BAHRI M.A., M.O.L., PH.D., D.LITT., SHASTRI * r ALLAHABAD EHflRflTI PRESS PUBLICATIONS DARBHANGA ROAD. Copyright, 1962 ^ Lahndi Phonology [Part II of the Thesis approved by the Punjab University, Lahore*. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1944]' Sole Distributors: LOKBHARATI 15-A, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, Allahabad—1. PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE BHARATI PRESS, DARBHANGA ROAD 'ALLAHABAD—2, i CONTENTS CONTENTS A WORD • iv CHART OF PHONETIC SYMBOLS AND PRONUNCIATION LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED vii INTRODUCTION ? ' ;" ix PHONOLOGY OF I-A. ELEMENT I* Preservations * ' II. Extinctions 13 III. Modifications IV# General^ Problems in Modifications 15$ V. Phonetic Semantic Modifications VI. Extensions (including History of Final Sounds) • VII. Onomatopoetic Formations 101 VIII. Agents of Change 11? '.]"•' IX. Possibilities (including Obscurities & Deshis of the Dialect) 14a : PHONOLOGY OF FOREIGN ELEMENT i X. Persian Element 155 XI. English Element 193 BIBLIOGRAPHY ' 209 INDEX OF LAHNDI WORDS AND SOUNDS 212 INDEX OF SOURCE SOUNDS 234 > INDEX OF SUBJECTS 237 # A WORD The present work is a part of the thesis submitted to the Punjab University, Lahore, in 1941 ^and approved for the degree -of Doctor of Philosophy in the Oriental Faculty. -

Opinions Cape Coral Breeze

WEEKEND EDITION POST COMMENTS AT CAPE-CORAL-DAILY-BREEZE.COM Inside PARADE Waiting • Sunday With Kelly Clarkson game Inside today’s Breeze: Wet weather douses Cape Coral Vote 2011: • American football games; Baker Stories: postponed to Saturday Candidate question of the Week A Chance Encounter, A Inside Lasting Bond cape-coral-daily-breeze.com cape-coral-daily- breeze.com CAPE CORAL BREEZE Vol. 50, No. 130 Saturday, October 29, 2011 50 Cents AT A GLANCE Calusa Blueway Paddling Festival opens Thursday the Calusa Blueway paddling trail. up paddling topics. The speakers will ‘Top 20’event an international draw The site provides ample parking talk about how to fish, how to buy and a nice beach area for the demos your first board, along with providing By MEGHAN McCOY lot of things this year. and classes. demos on the boards, Clayton said. [email protected] “It is the first time we have had a Activities will include the instruc- The festival will kick off with a The sixth annual Calusa Blueway consolidated spot where people can tional classes to be offered by certi- free photo reception event on Nov. 2 Paddling Festival — one of the go several days in a row ... kind of a fied paddling and kayak instructors at Rutenberg Park in Fort Myers at Southeast Tourism Society’s top 20 festival atmosphere,” she said. and demonstrations for those interest- 6:30 p.m. The photo session will events for 2011 — will take place That central location is Sanibel ed in learning about the latest and provide a little emphasis on how to Nov. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT to the FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE on PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996)

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT TO THE FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996) Prepared by: M. Sujayef Ullah Chowdhury Dhaka, April 1995 BANGLADESH country report 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the FAO International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources, Leipzig, Germany, 17-23 June 1996. The Report is being made available by FAO as requested by the International Technical Conference. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any option whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. BANGLADESH country report 3 Table of contents FOREWORD 5 PREFACE 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO BANGLADESH AND ITS AGRICULTURE 10 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.1 FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.2 MEDICINAL PLANTS 22 2.3 OTHER WILD SPECIES AND WILD RELATIVES OF CROP PLANTS 22 2.4 LANDRACES (“FARMERS’ VARIETIES”) AND OLD CULTIVARS 22 CHAPTER 3 NATIONAL CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 29 3.1 IN SITU CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 30 3.2 EX SITU COLLECTIONS -

NHC Menu February 20

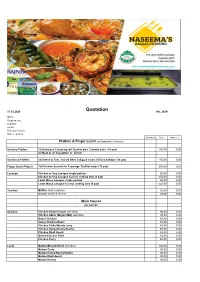

03 02 2020 Quotation No. 2020- Name Request no. Contact email Delivery Venue Date required Quantity Price Amount Platters & Finger Lunch (in Disposable Container) Savoury Platters 12xSamoosa 12xspring roll 12xmini pies 12xmeat balls (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 All Meat or all Veg option or all mix Sandwich Platters 3xCheese & Tom, 3xCold Beef, 3xEgg & salad, 3xTuna & Mayo (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 Finger lunch Platters 12xChicken drumsticks 12xwings 12xfillet strips (10 pax) 550,00 0,00 Lasange Chicken or Veg Lasagne single portion 60,00 0,00 Chicken or Veg Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 450,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne single portion 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 520,00 0,00 Tea time Muffins butter and jam 25,00 0,00 Scones butter & cheese 25,00 0,00 Main Course per person Chicken Chicken Biryani (layer) with dhay 80,00 0,00 Chicken Akhni (Biryani Mix) with dhay 70,00 0,00 Butter Chicken 65,00 0,00 Saucy Chicken Roast 65,00 0,00 Chicken Tikka Masala curry 65,00 0,00 Chicken Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 65,00 0,00 Chicken Dhall Gosht 65,00 0,00 Grilled Chicken Fillet 65,00 0,00 Chicken Curry 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mutton Biryani/Akhni with dhay 100,00 0,00 Mutton Curry 90,00 0,00 Mutton Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 90,00 0,00 Mutton Dhall Gosht 90,00 0,00 Mutton Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Grilled Masala Steak 90,00 0,00 Grilled T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Saucy Pepper Steak 90,00 0,00 Salt & Pepper Grilled Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Beef Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Korma/Kariha/Kaliya 90,00 0,00 Vegetable Vegetable Biryani/Akhni -

Released on 03 May 2012 STAR GROUP LTD. Page 1

Released On 03 May 2012 STAR GROUP LTD. Page 1 FOX Movies Premium PROGRAMME SCHEDULE FOR JUNE Friday, 01/06/2012 00:45 JONESES, THE (16)<2010> 02:25 PROM (PG)<2011> 04:10 OPEN SEASON (PG)<2006> 05:40 FAR FROM HOME: THE ADVENTURES OF YELLOW DOG (PG)<1995> 07:05 HAUNTED CHANGI (15)<2010> 08:30 RED WATER (15)<2003> 10:05 ROBOTS (PG)<2005> 11:40 LINCOLN LAWYER (15)<2011> 13:40 UNSTOPPABLE (12)<2010> 15:20 JONESES, THE (16)<2010> 17:00 FAR FROM HOME: THE ADVENTURES OF YELLOW DOG (PG)<1995> 18:25 BIG MOMMAS: LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON (15)<2010> 20:15 ONCE UPON A TIME S1 Ep4 The Price Of Gold(TBA)<2011> 21:00 HOMELAND S1 Ep9 CROSSFIRE(16)<2011> 22:00 RESIDENT, THE (15)<2011> 23:35 LINCOLN LAWYER (15)<2011> STAR GROUP LTD. Page 2 FOX Movies Premium PROGRAMME SCHEDULE FOR JUNE Saturday, 02/06/2012 01:35 REBOUND, THE (15)<2009> 03:10 ALIEN HUNTER (15)<2003> 04:45 ANACONDAS: THE HUNT FOR THE BLOOD ORCHID (15)<2004> 06:25 RESIDENT, THE (15)<2011> 08:00 FEW GOOD MEN, A (15)<1992> 10:20 SO I MARRIED AN AXE MURDERER (15)<1993> 11:55 DATE NIGHT (15)<2010> 13:25 ONCE UPON A TIME S1 Ep4 The Price Of Gold(TBA)<2011> 14:15 HOMELAND S1 Ep9 CROSSFIRE(16)<2011> 15:15 MADE OF HONOR (15)<2008> 17:00 MASK OF ZORRO, THE (15)<1998> 19:20 UNSTOPPABLE (12)<2010> 21:00 TREASURE ISLAND (PART 1 OF 2) (TBA)<2011> 23:35 TALLADEGA NIGHTS: THE BALLAD OF RICKY BOBBY (16)<2006> STAR GROUP LTD. -

About.Cherry.2012.Bluray.1080P

407 Dark Flight (2012) A Hijacking (2012) A.C.A.B All Cops Are Bastards (2012) About.Cherry.2012.BluRay.1080p.DTS.x264-CHD Aladdin and the Death Lamp (2012) All Superheroes Must Die (2012)' Allegiance (2012) Asterix And Obelix (2012) Back to the Sea (2012) Barricade (2012) Battleground (2012) Bidadari.Bidadari.Surga.2012 Bila (2012) Black’s Game (2012) Blood Money (2012)' Branded (2012) Chasing Mavericks (2012) Cirque du Soleil Worlds Away (2012) Company Of Heroes (2013) Cosmopolis (2012) Crawlspace (2012) Dabangg 2 (2012) Dark Shadows (2012) Dendam Sundel Bolong 2(011) Dendam.Dari.Kuburan.2012 Eden (2012) El Gringo (2012) Enak Sama Enak (2012) Extracted (2012) Fetih 1453 (2012) Girls Against Boys (2012) Hantu Tanah Kusir ( 2010 ) Hantu.Budeg.2012 Hitchcock (2012) Identity Thief (2013) Journey to the West- Conquering the Demons (2013) Jurassic Attack (2013) Kafan Sundel Bolong (2012) Kill for Me (2013) Killing Them Softly (2012) Lake Placid The Final Chapter (2012) Last Dance (2012) Les Miserables (2012) Life of Pi (2012) Lincoln (2012) Love Fiction (2012) Mafia (2011) Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola (2013) Motorway (2012) Paperman (2012) Partysaurus Rex (2012) Pitch Perfect (2012) Project X (2012) Rebelle (2012) Red Dawn (2012) Redd Inc (2012)' Riddle (2013) Rise Of The Guardians (2012) Smashed (2012) Spiders (2013) Starship Troopers Invasion (2012) Straight As (2013)' Super Man VS the Elite (2012) Tad The Lost Explorer (2012) The Factory (2012) The Hobbit An Unexpected Journey (2012) The Impossible (2012) The Marine 3 Homefront (2013) Tower -

Celebrating Israel's 70Th Annual Meeting Religious School Changes Selecting Summer Camp

TEMPLE BETH EL OF BOCA RATON MAY/JUNE 2018 | IYYAR/SIVAN/TAMUZ 5778 ANNUAL MEETINGpage 7 CELEBRATING ISRAEL’Spages 70TH 12-17 RELIGIOUS SCHOOL CHANGESpage 22 EHUD BARAK TEMPLE BETH EL HOSTS THE FORMER ISRAELI PRIME MINISTER page 5 SELECTING SUMMER CAMPpage 20 2 THE CHRONICLE | tbeboca.org If You Will It, BY RABBI DAN LEVIN It Is No Dream [email protected] May 14, 1948. That day of Israel’s is an extraordinary document. It birth encapsulates so much of Israel promises that Israel “will be open itself. It marked the realization of for Jewish immigration and for the a two-thousand year old dream to Ingathering of the Exiles; it will foster reestablish our home in the land of the development of the country for Israel. It prompted an existential the benefit of all its inhabitants; it threat from the new state’s Arab will be based on freedom, justice and residents and neighbors. It required peace as envisaged by the prophets of delicate and strong diplomacy to Israel; it will ensure complete equality placate allies. And the declaration of social and political rights to all its itself needed to take place on Friday inhabitants irrespective of religion, afternoon, hours before the mandate race or sex; it will guarantee freedom was officially terminated, because it of religion, conscience, language, could not take place on Shabbat. education and culture; it will safeguard As we celebrate the 70th anniversary the Holy Places of all religions…” It is of the birth of the State of Israel, we amazing how this tiny democracy, in the ancient stones of Jerusalem has see that how Israel balances all these so short a time, has done so much to grown a vibrant and multi-cultural challenges is the story of Israel itself. -

BIRYANI DISHES ENGLISH DISHES Biryani, Traditionally Known As Akhni (In Bangladesh), Is an Aromatic Pilau-Style Dish with Meat, Vegetables Or Seafood

BIRYANI DISHES ENGLISH DISHES Biryani, traditionally known as Akhni (in Bangladesh), is an aromatic pilau-style dish with meat, vegetables or seafood. Sirloin Steak ................................................................... 14.95 Originating from the Mughal cuisine of the 16th-19th centuries, it was a Served with fried onions and mushrooms, festive dish, costly to prepare and eaten mainly in the royal courts. hand cut chunky chips and salad. Chicken / Vegetable ........................................................9.95 Fish Bites and Chips......................................... 5.95 8.95 Chicken Tikka / Lamb...................................................10.95 Omelette and Chips.......................................... 5.95 8.95 A choice of chicken, mushroom, cheese or vegetable Prawn ......................................................................................10.95 served with chips and salad. King Prawn........................................................................... 13.95 Chicken Nuggets and Chips ........................ 5.95 8.95 The Spiced Mango Royal Mixed Biryani............. 14.95 Scampi and Chips.............................................. 5.95 8.95 SUNDRIES VEGETARIAN DISHES Steamed Basmati Rice .................................................... 2.25 Most of our Vegetarian dishes can be prepared to strict Vegan standards. Please inform a member of our waiting sta. Pilau Rice.................................................................................2.40 Coconut Rice........................................................................