Nauss-Jade-MA-ENGL-August-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Pioneer Life: Two Replies to Mr. Davis

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS THE STUDY OF PIONEER LIFE: TWO REPLIES TO MR. DAVIS MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA, January 24, 1930 DEAR EDITOR: Having in my boyhood days experienced the life and trials of a pioneer upon the prairies of western Minnesota, I was much interested in reading in your last quarterly the criticism by Le Roy G. Davis of certain incidents and statements contained in Rolvaag's Giants in the Earth.^ I read this rather remarkable book with a great deal of interest — an interest much enhanced because of my own personal con tact with frontier life and because I recognized in the story a substantially correct picture of conditions and the social life prevailing in those far-flung stretches lying out beyond " where the West begins." Mr. Davis selects a few statements from the book (I presume the most extreme he could find) and sets out to prove that a false picture is painted by the author. My own impression and feeHng is that Rolvaag's picture is true in substance and practically so in detail. I will briefly go over the several objections made by Mr. Davis: I. Mr. Rolvaag states that "original settlers are agreed that there was neither bird nor insect life on the prairie, with the exception of mosquitoes, the first year that they came." Mr. Davis challenges this statement. If I remember rightly, mention was made in the story of the passing of ducks and geese. With that qualification, I believe the statement to be substantially correct. Before the advent of the settler the open prairie, far removed from rivers, lakes, and trees, was practically devoid of bird life. -

Aftermath : Seven Secrets of Wealth Preservation in the Coming Chaos / James Rickards

ALSO BY JAMES RICKARDS Currency Wars The Death of Money The New Case for Gold The Road to Ruin Portfolio/Penguin An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2019 by James Rickards Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rickards, James, author. Title: Aftermath : seven secrets of wealth preservation in the coming chaos / James Rickards. Description: New York : Portfolio/Penguin, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019010409 (print) | LCCN 2019012464 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735216952 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Investments. | Financial crises. | Finance—Forecasting. | Economic forecasting. Classification: LCC HG4521 (ebook) | LCC HG4521 .R5154 2019 (print) | DDC 332.024—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010409 Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone. While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. -

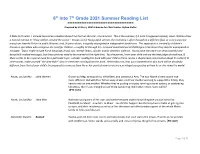

Rising Seventh Grade

6th into 7th Grade 2021 Summer Reading List ============================ Prepared by Liz Perry, SFWS Librarian for Class Teacher Alylssa Steller A Note to Parents: I include here some valuable advice from former librarian, Ann Grandin: This is the summer, if it hasn’t happened already, when children show a natural interest in “those shelves around the corner.” Known as the Young Adult section, the inventory is often housed on a different floor or a very separate area from Juvenile Fiction in public libraries, and, if space allows, is equally segregated in independent bookstores. This separation is created by children’s literature specialists who recognize the need for children – roughly 12 through 14 – to avoid moral and social challenges in literature they may be unprepared to navigate. Topics might include harsh language, drugs, sex, mental illness, suicide, and/or domestic violence. Young adult literature can send powerful and beautifully crafted messages, but these pictures need to be received at the right time. You the parent, know your child and are the best judge of readiness; if there seems to be a special need for a particular topic, consider reading the book with your child so there can be a shepherded conversation about its content; in other words, make yourself “the wise elder” who is sometimes missing from the book. Remember, too, that your interpretation of a book will be decidedly different from that of your child’s; be prepared to converse from his or her point of view to receive a privileged perspective on how he or she views the world. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Grown-up Meg, tomboyish Jo, timid Beth, and precocious Amy. -

Steph Scott ©2014 Adapting Snow White Today

Steph Scott ©2014 Adapting Snow White Today: Narrative and Gender Analysis in the Television Show Once Upon a Time Abstract: This paper examines the narrative in the first season of the ABC television show Once Upon a Time (2011-Present) and the fairytale Snow White (1857) with a particular focus on female gender representation. The reappearance of fairytales in popular media provides a unique opportunity to examine how values between two very different time periods have changed. Utilizing a narrative approach allows the research to show the merits and limitations across adapting from an old text to a television serial. Once Upon a Time offers a progressive rendition of the character Snow White by challenging both the traditional narrative and the television serial narrative. Snow White’s relationships with other characters are also expanded upon in the televised tale and surround her heroic acts, rather than her beauty, which changes the values presented in the television series. Methodology: In Once Upon a Time, throughout its narrative progression the traditional narrative is challenged. The first season’s episodes “Snow Falls,” “Heart is a Lonely Hunter,” “7:15AM,” “Heart of Darkness,” “The Stable Boy,” “An Apple Red as Blood,” and “A Land Without Magic” are given particular attention in this analysis because they pertain to Snow White’s fairytale. Robert Stam (2005) describes adaptation narrative analysis as considering “the ways in which adaptations add, eliminate, or condense characters” (p.34). With textual analysis of the first season of Once Upon a Time, these factors can be analyzed through Snow White’s relationships with other characters. -

Stories of Russian Life

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY Cornell University Library PG 3456.A15F31 Stories of Russian life, 3 1924 014 393 130 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924014393130 STORIES OF RUSSIAN LIFE STORIES OF RUSSIAN LIFE BY ANTON TCHEKOFF TRANSLATED FROM THE BtTSBIAN BT MARIAN FELL NEW YORK CHARLES SCEIBNER'S SONS 1914 -% r" 70 7 (> COFTBZGHT,A 1914, BT CHABLES SCBIBNER'S SONS Published May, 1914 CONTENTS FAOB 3 |. Qyeese4B^ed The Night befobe Easter 10 At Home 26 ''•^ ' Champagne *1 ^' The Malepactob ^0 Mtjbdeb Will OtTT 56 §3-' A" The Tbottsseau ' \&" ' The Decobation The Man in a Case 76 Little Jack ^' Dbeams ^ * ' The Death of an Official 118 Agatha ^^^ TheBbogab '^^^ Children 148 J^ The Tboublesome Guest 1^''' "^ Not Wanted ^^ "The RoBEEms l77 Fat 2°^ , . Lean and V vi CONTENTS PAPB On THE Wat 208 v/ The Head Gabdenek's Tale *3* -Hush! 240 t- WlTHOITT A TnUE 5-«» ^ In the Eavinb 252 STORIES OF RUSSIAN LIFE STORIES OF RUSSIAN LIFE OVERSEASONED ON arriving at Deadville Station, Gleb Smirnoff, the surveyor, found that the farm to which his business called him still lay some thirty or forty miles farther on. If the driver should be sober and the horses could stand up, the distance would be less than thirty miles; with a fuddled driver and old skates for horses, it might amount to fifty. "Will you tell me, please, where I can get some post-horses.'' " asked the surveyor of the station-master. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Europe the Way IT Once Was (And Still Is in Slovenia) a Tour Through Jerry Dunn’S New Favorite European Country Y (Story Begins on Page 37)

The BEST things in life are FREE Mineards’ Miscellany 27 Sep – 4 Oct 2012 Vol 18 Issue 39 Forbes’ list of 400 richest people in America replete with bevy of Montecito B’s; Salman Rushdie drops by the Lieffs, p. 6 The Voice of the Village S SINCE 1995 S THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 44 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 48 EuropE ThE Way IT oncE Was (and sTIll Is In slovEnIa) A tour through Jerry Dunn’s new favorite European country y (story begins on page 37) Let the Election Begin Village Beat No Business Like Show Business Endorsements pile up as November 6 nears; Montecito Fire Protection District candidate Jessica Hambright launches Santa Barbara our first: Abel Maldonado, p. 5 forum draws big crowd, p. 12 School for Performing Arts, p. 23 A MODERNIST COUNTRY RETREAT Ofered at $5,995,000 An architecturally significant Modernist-style country retreat on approximately 6.34 acres with ocean and mountain views, impeccably restored or rebuilt. The home features a beautiful living room, dining area, office, gourmet kitchen, a stunning master wing plus 3 family bedrooms and a 5th possible bedroom/gym/office in main house, and a 2-bedroom guest house, sprawling gardens, orchards, olives and Oaks. 22 Ocean Views Private Estate with Pool, Clay Court, Guest House, and Montecito Valley Views Offered at $6,950,000 DRE#00878065 BEACHFRONT ESTATES | OCEAN AND MOUNTAIN VIEW RETREATS | GARDEN COTTAGES ARCHITECT DESIGNED MASTERPIECES | DRAMATIC EUROPEAN STYLE VILLAS For additional information on these listings, and to search all currently available properties, please visit SUSAN BURNS www.susanburns.com 805.886.8822 Grand Italianate View Estate Offered at $19,500,000 Architect Designed for Views Offered at $10,500,000 33 1928 Santa Barbara Landmark French Villa Unbelievable city, yacht harbor & channel island views rom this updated 9,000+ sq. -

1 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 27, 2017 BC's Leo Awards Makes a Historic Move in Canada's Film & TV Industry for Acce

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 27, 2017 BC’s Leo Awards Makes a Historic Move in Canada’s Film & TV Industry for Accepting Gender-Fluid Performer in Both Male and Female Performance Categories Star of short film Limina gender-fluid eleven-year old Vancouver actor Ameko Eks Mass Carroll is being submitted into both Male and Female Performance categories for the Leo Awards. In a historic move, The Leo Awards, a Project of the Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences Foundation of British Columbia, has set a precedent in the Canadian Film and Television industry by accepting a gender-fluid performer’s request to be submitted into both Male and Female performance categories. "We are proud to join our colleagues at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in recognizing the importance of inclusivity when honouring artistic excellence" says Walter Daroshin, Chair of the Motion Picture Arts & Sciences Foundation of British Columbia and President of the Leo Awards.” Ameko Eks Mass Carroll, an eleven year-old Vancouver performer, stars in the short film entitled Limina, directed and produced by Vancouver-based filmmakers Florian Halbedl and Joshua M. Ferguson. Ameko plays gender- fluid protagonist, Alessandra, in Limina and also identifies as gender-fluid and uses he/him/his pronouns. Ameko identifies as a boy and other days as a girl and some days as neither. The filmmakers have submitted Ameko’s performance into both Male and Female Performance categories for the Leo Awards. Ameko says, “I would love to give the Leo Awards a ginormous thanks for making people under the trans umbrella feel more welcomed in the world. -

Educator's Guide

educator’s guide Curriculum connections D Fairytales D Fantasy D Fiction Ages 8 & up By Chris Colfer AT THE CORE: APPLYING students gather in groups (with students who all have different stories). Have students take turns telling the RESEARCH TO PRacTICE story they learned about. To help students stay focused and become aware of any misconceptions they might have Upon first glance, the movement in education toward had, use an anticipation guide. Students can fill out the development of a common set of standards and practices “Before Jigsaw” section showing what they thought before can make the creative teacher feel stifled and threatened. the exercise, and then they can fill out the “During/After If teachers are focused on meeting all of these standards, Jigsaw” section to show what they learned. (See Blackline how will there be time to include lessons that stretch Masters for an example of an anticipation guide to use students’ imaginations or foster their love for literature, with this lesson.) history, and the sciences? The truth is, if standards are truly going to improve student learning outcomes, then they must do all of these things. The ideas set forth in this MAKING CONNECTIONS guide are designed to address many of the Common Core standards in reading, writing, and social studies. They Allusion are designed to challenge students to examine, analyze, and critique arguments. They are focused on explicitly An allusion is a reference in a literary work to a person, teaching students to connect their learning and to develop place, or thing in history or another work of literature. -

BYTOMSKIE •A Ukazuje Się Od 1956R

977023929470903 > Z mandoliną Egzotyczne podróże Magdaleny Goik 9 770239 2947 nad przeręblą ZYCIE BYTOMSKIE •A Ukazuje się od 1956r. w Bytomiu i Radzionkowie • 3 (3107) • 16.01.2017 wydanie elektroniczne PL ISSN 0239-2941 • NR INDEKSU 385050 • ROK LXI • NAKŁAD: 9.000 (udokumentowany) dostępne na eprasa.pl Czytaj str. 12 Cena 2 zł (w tym 8% VAT) www.zyciebytomskie.pl Pijemy coraz więcej, choć nas coraz mniej Czytaj str. 2 Śnieżna górka z bytomskiego Rynku rozgrzała ogólnopolskie emocje 37-latek urządził w mieszkaniu plantację marihuany O G Ł O S Z E N I A ŻYCIE BYTOMSKIE' Zostań Opiekunką osób starszych w Niemczech OP EKUNKI partners ajB tntDJOB r-cKncD CENTER 32 395 88 83 w wersji elektronicznej www.ajpartners.pl na eprasa.pl Gwarantujemy bezpłatny kurs Języka niemieckiego 2 16.01.2017 Życie miasta Pijąc, często przesadzamy. W roku 2015 do bytomskiej izby Przepiliśmy 150 milionów złotych wytrzeźwień doprowadzono 6547 osób, a więc średnio niemal 18 Mamy problem. Pijemy mnóstwo alkoholu. Z roku na otworem placówki całodobowe. Bytomiem, kupując tam napoje każdego dnia. Gros z nich stanowi Przy takich możliwościach obrót wyskokowe. Ze wspomnianych 150 li mężczyźni - 5501. Kobiet w izbie rok coraz więcej. W roku 2015 na piwo, wino i wódkę wy musi być ogromny, a przynajmniej mln z hakiem ponad połowę prze zatrzymano 936, niestety byli też daliśmy przeszło 150 milionów złotych! Wielu spośród nas łatwiej go osiągnąć. Jak obliczono, znaczyliśmy na piwo, 13 mln na nieletni: 98 chłopców i 12 dziew w ciągu dwunastu miesięcy miesz napoje zawierające do 18 procent cząt. W ogóle we wspomnianym jest uzależnionych i ma z tego powodu ogromne problemy. -

Nicholas A. Virgilic 1092 Niagara Road Camden 4, New Jersey

Nicholas A. Virgilic 1092 Niagara Road Camden 4, New Jersey Two little girls spinning on stools} singing, Its tiny paws hold the child counting the same f ir e fly one acorn, and only one ever and over in this gnawing cold. The broken hoe handle \ before the old tree,,* that served as the scarecrow saplings in the wind and sun holds the hobo's cloth es• practice calligraphy. \ ■' .The old house's e ave s In the tw ilight fie ld - whiakering with icicles: a child counts the same firefly the Chinese laundry, over and o v e r ... In the twilight fie ld - innt a child counts the same firefjLy in the old stable - arain and again... the horse's leg twitches a fly A butterfly A white butterfly fanning a wilting flower bouncing on the ball diamond marking the base-line The summer heat: A butterfly a fluttering butterfly playing a melody on the base-liae fanning a flower The b a ll diamond; X \ a butterfly-melody The clouded sun; follows the base-line wiping the window she polishes her siaile My spring-cleaning neighbor These pampas plumes waving in the autumn wind, would a rake a tine broom Nicholas A* Virgilic 1092 Niagara Road Camden 4, New Jersey Heavy, summer day*** how does o The armies a scarecrows p ihe old muddy shoes and the rusty tackle box a hobo shouldering of my fishing youth. The armless scarecrow a hobo shoulders the hoe handle and a bundle of clothes. renting the roff of storm clouds Crisscrossing sunbeams renting the overcasts city sky lin e . -

Winter Weather Awareness Day 2010

Nebraska Winter Weather Awareness Day Winter Weather Awareness Day - November 4, 2010 With Fall upon the Great Plains, now is the time to focus attention to winter weather and the dangers it can pose to life and property. November 4th, 2010 has been declared as Winter Weather Awareness Day for the state of Nebraska. Each year, dozens of Americans die due to exposure to the cold. Winter weather accounts for vehicle accidents and fatalities, and results in fires due to dangerous use of heaters and other winter weather fatalities. Other hazards, such as hypothermia and frostbite, can lead to the loss of fingers and toes or cause permanent internal injuries and even death. The very young and the elderly are among those most vulnerable to the potentially harsh winter conditions. Recognizing the threats and knowing what to do when they occur could prevent the loss of extremities or save a life. A winter storm can last for several days and be accompanied by high winds, freezing rain or sleet, heavy snowfall and cold temperatures. People can be trapped at home or in a car with no utilities or assistance, and those who attempt to walk for help could find themselves in a deadly situation. The aftermath of a winter storm can have an impact on a community or region for days, weeks, or possibly months. Wind - Some winter storms have extremely strong winds which can create blizzard conditions with blinding, wind driven snow, drifting, and dangerous wind chills. These intense winds can bring down trees and poles, and can also cause damage to homes and other buildings.