The Conquest of Central Asia, 1780

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

'Great Game': the Russian Origins of the Second Anglo-Afghan

Beyond the ‘Great Game’: the Russian origins of the second Anglo-Afghan War* ALEXANDER MORRISON Department of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Abstract Drawing on published documents and research in Russian, Uzbek, British and Indian archives, this article explains how a hasty attempt by Russia to put pressure on the British in Central Asia unintentionally triggered the second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878 - 80. This conflict is usually interpreted within the framework of the so-called 'Great Game', which assumes that only the European 'Great Powers' had any agency in Central Asia, pursuing a coherent strategy with a clearly-defined set of goals and mutually-understood rules. The outbreak of the Second Anglo-Afghan war is usually seen as a deliberate attempt by the Russians to embroil the British disastrously in Afghan affairs, leading to the eventual installation of 'Abd al-Rahman Khan, hosted for many years by the Russians in Samarkand, on the Afghan throne. In fact the Russians did not foresee any of this. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s ascent to the Afghan throne owed nothing to Russian support, and everything to British desperation. What at first seems like a classic 'Great Game' episode was a tale of blundering and unintended consequences on both sides. Central Asian rulers were not merely passive bystanders who provided a picturesque backdrop for Anglo-Russian relations, but important actors in their own right. Introduction ‘How consistent and pertinacious is Russian policy! How vacillating and vague is our own!' Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1885.1 At the crossroads of Sary-Qul, near the village of Jam, at the south-western edge of the Zarafshan valley in Uzbekistan, there is an obelisk built of roughly-squared masonry, with a rusting cross embedded near the top. -

New Great Game and Limits of American Power

38 IPRI Journal XIV,New no.Great 1 (WinterGame and 2014): Limits 38 of- 65American Power New Great Game and Limits of American Power Air Cdre. (R) Naveed Khaliq Ansaree Abstract The „New Great Game‟ is the global rivalry between the US- NATO bloc and its allies and their Counter-Alliance Camp. In the grand strategic calculus of Russia-China-Pakistan- Afghanistan-India entanglement, the US Camp seems to be losing its strategic foothold, particularly in Eurasia. The US‟ „Pivot to Asia‟ may also suffer serious setbacks. The deals on Syria‟s chemical weapons and Iran‟s nuclear programme have brought the Middle East under a „Strategic Pause‟ but have also exposed the limits of American power. Afghanistan is on the tipping-point of proving or disproving to be the „graveyard of empires‟. The danger of Saudi Arabia becoming the victim of a fresh „Arab Spring‟ as well as destabilization of Pakistan has increased manifold. The US‟ latest offer for full-spectrum revival of strategic alliance could merely be a „Strategic Deception‟ for Pakistan. The US-Iran nuclear deal may also manifest into additional space for US strategy and lines of operations for Afghanistan-Pakistan. Iran and Syria could be re-visited in the next cycle. Strategic wisdom is hoped to prevail amongst regional stake-holders. Any strategic failure of the US strategy could further expose the limits of American power. The dynamics could roll the ball for a new balance of power; thus shrinking the area of US imperialism and opening up spaces for the manifestation of „Chi-Merica‟ (China- America) or a multi-polar world. -

Abashin, S.N., Arapov, D

Abashin, S.N., Arapov, D. Yu. & Bekmakhanova, N.E. (ed.) & authorial collective Tsentral’naya Aziya v Sostave Rossiiskoi Imperii (Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie) 2008 464 pp.; 8 Appendices pp.339-424; Bibliography pp.425-32; glossary pp.433-8, Index of names pp.439-45; ISBN 978-5-86793-571-9 This useful and significant book is the latest in the Series Okrainy Rossiiskoi Imperii (Historia Rossica) whose general editors are Alexei Miller, Anatoly Remnev & Alfred Rieber. The authorial collective of S. N. Abashin, D. Yu. Arapov, N. E. Bekmakhanova, O. V. Boronin, O. I. Brusina, A. Yu. Bykov, D. V. Vasiliev, A. Sh. Kadyrbaev, T. V. Kotyukov, P. P. Litvinov, N. B. Narbaev & Zh. S. Syzdykova includes some of the finest of the first post-Soviet generation of Russian-language scholars working on the Islamic regions of the Empire, although the sheer number who have contributed inevitably leads to unevenness of tone and occasional contradictions. This book is an important milestone in the development of what can tentatively be called ‘postcolonial’ (or at any rate post- Imperial) Russian historiography. It aims to be a standard work of reference on the place of Central Asia (which here includes the territory of modern Kazakhstan) within the Russian Empire, and in purely factual terms it largely succeeds: there is as yet no equivalent of this volume in English, not least because much recent western scholarship on Central Asia has perhaps concentrated too much on applying the latest theoretical innovations to the study of Russian Imperialism without first laying the sort of empirical foundations this book provides. -

Great Game to 9/11

Air Force Engaging the World Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland COVER Aerial view of a village in Farah Province, Afghanistan. Photo (2009) by MSst. Tracy L. DeMarco, USAF. Department of Defense. Great Game to 9/11 A Concise History of Afghanistan’s International Relations Michael R. Rouland Washington, D.C. 2014 ENGAGING THE WORLD The ENGAGING THE WORLD series focuses on U.S. involvement around the globe, primarily in the post-Cold War period. It includes peacekeeping and humanitarian missions as well as Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom—all missions in which the U.S. Air Force has been integrally involved. It will also document developments within the Air Force and the Department of Defense. GREAT GAME TO 9/11 GREAT GAME TO 9/11 was initially begun as an introduction for a larger work on U.S./coalition involvement in Afghanistan. It provides essential information for an understanding of how this isolated country has, over centuries, become a battleground for world powers. Although an overview, this study draws on primary- source material to present a detailed examination of U.S.-Afghan relations prior to Operation Enduring Freedom. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Cleared for public release. Contents INTRODUCTION The Razor’s Edge 1 ONE Origins of the Afghan State, the Great Game, and Afghan Nationalism 5 TWO Stasis and Modernization 15 THREE Early Relations with the United States 27 FOUR Afghanistan’s Soviet Shift and the U.S. -

When Everyone Is Dead the Great Game Is Finished

Peter John Brobst. The Future of the Great Game: Sir Olaf Caroe, India's Independence, and the Defense of Asia. Akron: University of Akron Press, 2005. xx + 199 pp. $39.99, cloth, ISBN 978-1-931968-10-2. Reviewed by Michael Silvestri Published on H-Albion (April, 2006) The "Great Game," Britain's struggle with Rus‐ Sir Olaf Caroe, "British India's leading geopo‐ sia for imperial supremacy in central Asia, seems litical thinker during the fnal years of the Raj" (p. at frst glance to belong to the age of the "New Im‐ xiv), came from a background that epitomized the perialism" of the late nineteenth century. First "official mind" of the British Empire. The son of a and foremost, it evokes the romantic--and fction‐ prominent architect, he was educated at Winches‐ al--exploits of Colonel Creighton, Mahbub Ali and, ter and Oxford (where he read classics) and saw of course, the title character of Rudyard Kipling's action on the Afghan frontier during the First Kim on India's Northwest frontier. In reality, the World War. Caroe enjoyed a distinguished career Great Game continued into the era of decoloniza‐ in the Indian Political Service, and served in the tion and the Cold War. In the closing years of the North-West Frontier (acquiring fuency in Pashto), British Raj, the Government of India wrestled Baluchistan and the Persian Gulf. In 1939 he took with the question of how Britain could continue charge of the External Affairs Department as for‐ to project influence in the region following a eign secretary to the Government of India. -

Nick Fielding

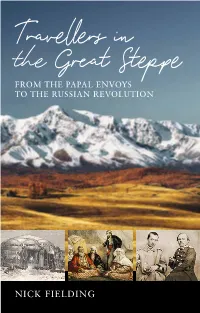

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Chronology of the Aral Sea Events from the 16Th to the 21St Century

Chronology of the Aral Sea Events from the 16th to the 21st Century Years General Events 16th century 1558 An English merchant and diplomat, Anthony Jenkinson, travels through Central Asia and observes the medieval desiccation of the Aral Sea. He writes that ‘‘the water that serveth all to country is drawn by ditches out of the river Oxus [old name for Amudarya] into the great destruction of the said river, for which it falleth not into the Caspian Sea as it gath done in times past, and in short time all land is like to be destroyed, and to become a wilderness foe want of water when the river Oxus shall fail.’’ A. Jenkinson crosses the Ustyurt and visits Khiva and Bukhara, preparing a map of Central Asia. 1573 ‘‘Turn’’ of the Amudarya from the Sarykamysh to the Aral; in other words, the rather regular flow of part of its waters into the Sarykamysh ceases, the waters from this time running only to the Aral. 17th century 1627 In the book, ‘‘Knigi, glagolemoy Bolshoy Chertezh’’ (‘‘the big sketch’’), the Aral Sea is named ‘‘The dark blue sea.’’ 1670 German geographer Johann Goman publishes the map ‘‘Imperium pereicum,’’ on which the Aral is represented as a small lake located 10 German miles from the northeastern margin of the Caspian Sea. 1697 On Remezov’s map of the Aral Sea (more Aral’sko), it is for the first time represented as an internal lake completely separated from the Caspian Sea and into which the Amundarya (Amu Darya, Oxus), the Syrt (Syr Darya, Yaksart), and many small rivers flow. -

“The Great Game” in Foreign Historiography

International Journal of Academic and Applied Research (IJAAR) ISSN: 2643-9603 Vol. 5 Issue 2, February - 2021, Pages: 51-56 “The Great Game” in foreign historiography Radjabov Ozodbek Aminboyevich National University of Uzbekistan Abstract: The second half of the nineteenth century was a critical period in British foreign policy for competition around the world, especially in Central Asia, and a significant turning point in the development of the confrontation between Britain and Russia in the region. The Crimean War of 1854-1856 and the Indian Uprising of 1857-185 had a profound effect on the state of international relations in the region, and the role of British authors in India's British Empire, Anglo-Russian rivalry, and the study of the aims and objectives of the British Empire in Central Asia. undadi. XIX The second half of the twentieth century was a period of formation of the "Big Game" political process in the context of growing competition between the two great powers Russia and Great Britain, which influenced the creation of political and historical works of British authors. Keywords: “Great game”, India, Russia, England, Ost-India, The Russo-Indian Question , Afghanistan I. Introduction. organizations began to study the history of the East and In 1857, the Great Sipahi Revolt against the British publish works of orientalists. In terms of the importance of Empire began in India. It can be said that this revolt posed a British colonial policy in the East, the Department of serious threat to the continuation of British rule in India. As Colonial History was established at Oxford University, and a result, the British government was forced to carry out a the Center for Oriental Studies was established at the series of reforms in India. -

The Legend of the Great Game

ELIE KEDOURIE MEMORIAL LECTURE The Legend of the Great Game MALCOLM YAPP School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London A PERSISTENT THEME IN THE WRITINGS of Elie Kedourie was his mistrust of large, seemingly attractive concepts or ideas, ideas which were lightly advanced and quietly incorporated into political or historical folklore without being subjected to the close and critical scrutiny which he rightly believed to be an obligation of statesman and historian alike. One such concept is that of the Great Game and it is my intention in this lecture to examine the historical ethnology of this famous phrase and to offer some comments on its significance and value. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan at Christmas 1979 gave the phrase a new lease of life. The association of Russia and Afghanistan was irresistible and the upheaval was pronounced to be another round in the Great Game, understood to be a contest for mastery in Central Asia which had begun in the early nineteenth century. We were regaled with some strange geography and some curious history. Pakistan’s Khyber Pass was awarded to Afghanistan, Dr Brydon rode inaccurately again and Roberts marched in the wrong direction at the wrong time. Subsequently, the term ‘the Great Game’ was applied to what was seen as a new contest between the USSR and the USA and to the struggle for control of oil resources in the region of the Caspian Sea.1 Read at the Academy 16 May 2000. 1 The Times, 26 Nov. 1999, 7 Feb. 2000; Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia (2000). -

Herat: the Key to India

Herat: The Key to India The Individual Fears and Plans that Shaped the Defense of India During the Great Game By Trevor Lawrence Borasio Defended April 6, 2018 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Lucy Chester, History Honors Council Representative: Dr. Matthew Gerber, History Outside Reader: Dr. Jennifer Fluri, Geography Borasio 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Key Individuals 4 Map of Persia and Afghanistan 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One: Growing Fears and Master Plans 19 Chapter Two: A Herat-Centered Forward Policy 33 Chapter Three: The Rise and Fall of Herat’s Importance 55 Chapter Four: The Panjdeh Crisis 76 Conclusion: Herat: From Obsession to Obscurity 95 Bibliography 107 Borasio 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to the University of Colorado History Department, who inspired me as an undeclared freshman to follow my passion and pursue a degree in History. The amazing faculty that I have had the honor to work with perpetually inspire me be a better historian. Thank you to Dr. Fred Anderson, whose two rules of history continue to push me to write better histories. Thank you to Dr. Matthew Gerber, for guiding me through this thesis and demonstrating how rewarding it can be to finish the process. Thank you to Dr. Jennifer Fluri in the Geography department for always being available to suggest another book and push my research further. Thank you to Dr. Lucy Chester, for inspiring my interest in British imperial history in Central Asia, editing countless drafts of this thesis, pushing me to unearth further stories, and being constantly encouraging. Thank you to Dr. Anne Lester and the Undergraduate Studies Committee for awarding me the Charles R. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process.