Redalyc.CENTRAL ASIA: the BENDS of HISTORY AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Style Template and Guidelines for AIC2007 Proceedings

e-ISSN : 2620 3502 International Journal on Integrated Education p-ISSN : 2615 3785 Bilingualism As A Main Communication Factor For Integration Among Nations In Transoxiana, Modern Uzbekistan Dilnoza Sharipova1, Nargiza Xushboqova2, Mavjuda Eshpo’latova3, Mukhabbat Toshmurodova4, Dilfuza Shakirova5, Dildora Toshova6 1Department of Interfaculty Foreign Languages, Bukhara State University, [email protected] 2British School of Tashkent, Tashkent city 3Secondary School 2, Gijduvan, Bukhara region 4Department of English Language, Tashkent State University of Economics 5Department of English Language, Tashkent State University of Economics 6Secondary School 56, Gijduvan, Bukhara region ABSTRACT As we learn the history of language the national language requires understanding of the terms of fluent and linguistic methodology. Every language is primarily a historical necessity which changes the communication system. This information system is regulated or naturally will be developing by ages. Historically changes in Transoxiana region, modern Uzbekistan influenced in different forms and styles. In this paper work authors studied historical reformation of languages in this region. By centuries formation of the languages and their affect to the local communication and literature are studied. Moreover, authors clarified development of the Turkic language in Transoxiana and current reforms in education system which directed knowledge’s recognized internationally. Keywords: Transoxiana, language, bilingualism, tribes, Turkic, civilization era, Uzbek, international relations, reforms . 1. INTRODUCTION Language is a great social phenomenon, which has a great importance in the honor of every nation and country serves for its historical well-being and universal progress, consolidation of the country and self-awareness. It was said that the language is a great treasure that embodies the history, cultural heritage, lifestyle, traditions and traditions of the nation, its own language and its development represent the spiritual essence of the nation. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

INNER ASIAN WAYS of WARFARE in HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Nicola Di Cosmo the Military Side Of

INTRODUCTION: INNER ASIAN WAYS OF WARFARE IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Nicola Di Cosmo The military side of the "expansion of Europe" has been closely associated, especially in the writings of historians such as Geoffrey Parker, with the technological and tactical transformation of the European battlefields and fortifications known as the "military rev olution." Mastery of sophisticated weapons gave Europe's armies a distinct advantage that allowed them to prevail-by and large-in military confrontations against extra-European societies, perhaps slowly and accidentally at first, but rather effectively and purposefully from at least the late eighteenth century onward. Only certain areas of the world were not penetrated or dominated quite as effectively, and these are the areas identified by Halford J. Mackinder, the influential geographer, politician, and military theoretician, as the "heartland" of Eurasia, defined as the "pivot of history."' The heartland was inac cessible to sea-power, and yet could be easily crossed, in antiquity, by horsemen and camelmen, and later on by the railways. Mackinder recognized the historical role played by the steppes of Central Asia in military terms, and regarded Russia as the successor to the Mongols, that is, a power endowed with the same advantages and limitations as the great Eurasian empires created by the Inner Asian nomads. If, according to "pivot" theory, the larger currents of world history especially military history-have revolved for ages around the heart land of Eurasia (or Central Eurasia, or even Inner Eurasia),2 one can also say that the geopolitical rationale of this theory is not negated 1 An abridged version of Mackinder's theory has been recently reprinted in a voluminous anthology of military history: Gerard Chaliand, 1he Art ef War in World History, pp. -

Inner Asia Brill.Com/Inas

Inner Asia brill.com/inas Instructions for Authors Scope Published bi-annually by Global Oriental for the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit (MIASU) at the University of Cambridge, Inner Asia (INAS) is a peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary journal with emphasis on the social sciences, humanities and cultural studies. First published in 1999, Inner Asia is currently one of the very few research-orientated publications in the world in which scholars can address the contemporary and historical problems of the region. Ethical and Legal Conditions The publication of a manuscript in a peer-reviewed work is expected to follow standards of ethical behavior for all parties involved in the act of publishing: authors, editors, and reviewers. Authors, editors, and reviewers should thoroughly acquaint themselves with Brill’s publication ethics, which may be downloaded here: brill.com/page/ethics/publication-ethics-cope-compliance. Submission For further information, contact: Libby Peachey, Managing Editor MIASU, the Mond Building Free School Lane Cambridge CB2 3RF, UK E-mail: [email protected] http://www.innerasiaresearch.org Submission Requirements Language Please use UK English spelling (including -ise/-ising rather than -ize/-izing) and double-check all non- English words. Spelling should be consistent throughout. Font If you use a special font, please send us a copy of the font too. Punctuation Use only one space after a full stop. When an abbreviated word comes at the end of a sentence, there is only one full stop: Last revised on 17 December 2019 page 1 of 6 Inner Asia brill.com/inas Instructions for Authors … in the European countries, France, Italy, etc. -

Impaginato Ocnus 19.Indd

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM - UNIVERSITÀ DI BOLOGNA OCNUS Quaderni della Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Archeologici 19 2011 ESTRATTO Direttore Responsabile Sandro De Maria Comitato Scientifico Sandro De Maria Raffaella Farioli Campanati Richard Hodges Sergio Pernigotti Giuseppe Sassatelli Stephan Steingräber Editore e abbonamenti Ante Quem soc. coop. Via San Petronio Vecchio 6, 40125 Bologna tel. e fax + 39 051 4211109 www.antequem.it Redazione Enrico Gallì Collaborazione alla redazione Simone Rambaldi Abbonamento € 40,00 Richiesta di cambi Dipartimento di Archeologia Piazza San Giovanni in Monte 2, 40124 Bologna tel. +39 051 2097700; fax +39 051 2097802 Le sigle utilizzate per i titoli dei periodici sono quelle indicate nella «Archäologische Bibliographie» edita a cura del Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Autorizzazione tribunale di Bologna n. 6803 del 17.4.1988 Senza adeguata autorizzazione scritta, è vietata la riproduzione della presente opera e di ogni sua parte, anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, compresa la fotocopia, anche ad uso interno o didattico. ISSN 1122-6315 ISBN 978-88-7849-063-5 © 2011 Ante Quem soc. coop. INDICE Presentazione di Sandro De Maria 7 ARTICOLI Questioni di metodo Antonio Curci, Alberto Urcia L’uso del rilievo stereofotogrammetrico per lo studio dell’arte rupestre nell’ambito dell’Aswan Kom Ombo Archaeological Project (Egitto) 9 Pier Luigi Dall’aglio, Carlotta Franceschelli Pianificazione e gestione del territorio: concetti attuali per realtà antiche 23 Culture della Grecia, dell’etruria e di roma Claudio Calastri Ricerche topografiche ad Albinia (Grosseto) 41 Maria Raffaella Ciuccarelli, Laura Cerri, Vanessa Lani, Erika Valli Un nuovo complesso produttivo di età romana a Pesaro 51 Pier Luigi Dall’aglio, Giuseppe Marchetti, Luisa Pellegrini, Kevin Ferrari Relazioni tra urbanistica e geomorfologia nel settore centrale della pianura padana 61 Giuliano de Marinis, Claudia Nannelli Un “quadrivio gromatico” nella piana di Sesto Fiorentino 87 Enrico Giorgi, Julian Bogdani I siti d’altura nel territorio di Phoinike. -

A Case Study of an Early Islamic City in Transoxiana: Excavations at the Medieval

A Case Study of an Early Islamic city in Transoxiana: Excavations at the Medieval Citadel in Taraz, Kazakhstan Giles Dawkes and Gaygysyz Jorayev Centre for Applied Archaeology, UCL Institute of Archaeology Word Count: c. 4,700 Correspondence to: Giles Dawkes Centre for Applied Archaeology Units 1 and 2 2 Chapel Place Portslade East Sussex BN41 1DR 01273 426830 [email protected] [email protected] 1 This report presents a summary of the 2011 and 2012 excavations of the joint UK-Kazakhstani excavations in the medieval citadel of Taraz. The city of Taraz, located near the southern border with Uzbekistan, is one of the most significant historic settlements in Kazakhstan, and the investigations in the central market place have started to reveal the composition of the medieval city. Despite frequent mentions in Arabic and Chinese written sources, the form and evolution of this important Silk Road city remains poorly understood. These excavations, which identified a series of buildings including a bathhouse and a fire shrine, are the first for almost 50 years and include the first C14 radiocarbon date from the city. In addition, this is one of the first detailed accounts in English of an urban excavation in Kazakhstan. KEYWORDS: Kazakhstan, Early Islamic, Bathhouse, Fire Shrine, Urbanisation 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION This report presents a summary of the 2011 and 2012 excavations of the joint UK-Kazakhstani excavations in the medieval citadel of Taraz. The excavations were undertaken by two commercial archaeology companies, Archeological Expertise (Kazakhstan) and the Centre for Applied Archaeology (CAA), the contracting division of University College London (UCL) UK. -

Central Asia After Fifteen Years of Transition:Growth, Regional

Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No. 3 Central Asia after Fifteen Years of Transition: Growth, Regional Cooperation, and Policy Choices by Malcolm Dowling and Ganeshan Wignaraja July 2006 Office of Regional Economic Integration The ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration focuses on topics relating to regional cooperation and integration in the areas of infrastructure and software, trade and investment, money and finance, and regional public goods. The Series is a quick-disseminating, informal publication that seeks to provide information, generate discussion, and elicit comments. Working papers published under this Series may subsequently be published elsewhere. Key words: growth, economic reform, regional cooperation, industrial competitiveness, Central Asia, transitional economies. JEL Classifications: F15, P20, N10, O40 . Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. 2 Central Asia after Fifteen Years of Transition: Growth, Regional Cooperation, and Policy Choices Malcolm Dowling Singapore Management University, Singapore e-mail: [email protected] Ganeshan Wignaraja Office of Regional Economic Integration, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines Tel: 63 2 632 6116 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents a coherent and systematic analysis of the collapse and subsequent revival of the Central Asian Republics (CARs) since 1990. -

The Silk Road in World History

The Silk Road in World History The New Oxford World History The Silk Road in World History Xinru Liu 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Liu, Xinru. The Silk Road in world history / Xinru Liu. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8; ISBN 978-0-19-533810-2 (pbk.) 1. Silk Road—History. 2. Silk Road—Civilization. 3. Eurasia—Commerce—History. 4. Trade routes—Eurasia—History. 5. Cultural relations. I. Title. DS33.1.L58 2010 950.1—dc22 2009051139 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Frontispiece: In the golden days of the Silk Road, members of the elite in China were buried with ceramic camels for carrying goods across the desert, hoping to enjoy luxuries from afar even in the other world. -

Abashin, S.N., Arapov, D

Abashin, S.N., Arapov, D. Yu. & Bekmakhanova, N.E. (ed.) & authorial collective Tsentral’naya Aziya v Sostave Rossiiskoi Imperii (Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie) 2008 464 pp.; 8 Appendices pp.339-424; Bibliography pp.425-32; glossary pp.433-8, Index of names pp.439-45; ISBN 978-5-86793-571-9 This useful and significant book is the latest in the Series Okrainy Rossiiskoi Imperii (Historia Rossica) whose general editors are Alexei Miller, Anatoly Remnev & Alfred Rieber. The authorial collective of S. N. Abashin, D. Yu. Arapov, N. E. Bekmakhanova, O. V. Boronin, O. I. Brusina, A. Yu. Bykov, D. V. Vasiliev, A. Sh. Kadyrbaev, T. V. Kotyukov, P. P. Litvinov, N. B. Narbaev & Zh. S. Syzdykova includes some of the finest of the first post-Soviet generation of Russian-language scholars working on the Islamic regions of the Empire, although the sheer number who have contributed inevitably leads to unevenness of tone and occasional contradictions. This book is an important milestone in the development of what can tentatively be called ‘postcolonial’ (or at any rate post- Imperial) Russian historiography. It aims to be a standard work of reference on the place of Central Asia (which here includes the territory of modern Kazakhstan) within the Russian Empire, and in purely factual terms it largely succeeds: there is as yet no equivalent of this volume in English, not least because much recent western scholarship on Central Asia has perhaps concentrated too much on applying the latest theoretical innovations to the study of Russian Imperialism without first laying the sort of empirical foundations this book provides. -

The Conquest of Central Asia, 1780

Introduction: Killing the 'Cotton Canard' and getting rid of the 'Great Game'. Rewriting the Russian conquest of Central Asia, 1814 – 1895 Alexander Morrison Nazarbayev University [email protected] ‘Они забыли дни тоски, Ночные возгласы: «К оружью», Унылые солончаки И поступь мерную верблюжью’ ‘They have forgotten days of melancholy, Forgot the night-time call ‘To arms’! Forgot the dismal salty steppe And the camel’s measured tread.’ Nikolai Gumilev Turkestanskie Generaly (1911) Russia’s expansion southwards across the Kazakh steppe into the riverine oases of Turkestan was one of the nineteenth century’s most rapid and dramatic examples of imperial conquest. With its main phases sandwiched between the British annexation of the Indian subcontinent between 1757 and 1849, and the ‘Scramble for Africa’ initiated by the British occupation of Egypt in 1881-2, roughly contemporaneous with the French conquest of Algeria, it has never been granted the same degree of historical attention as any of these. In general, as Dominic Lieven has observed (2006 I, 3), studies of the foreign policy of the Russian empire are few and far between, and those which exist tend to take a rather grand, sweeping view of events rather than examining particular episodes in detail (Fuller 1998; LeDonne 1997 & 2004). Whilst there are both classic and recent explorations of the ‘Eastern Question’ and the Russian conquest of the Caucasus (Anderson 1966; Bitis 2006; Baddeley 1908; Gammer 1994), and detailed studies in English of Russian expansion in the Far East (Quested 1968; Bassin 1999; Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2001), the principal phases of the Russian conquest of Central Asia remain neglected and misunderstood. -

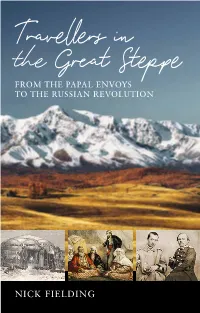

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Chronology of the Aral Sea Events from the 16Th to the 21St Century

Chronology of the Aral Sea Events from the 16th to the 21st Century Years General Events 16th century 1558 An English merchant and diplomat, Anthony Jenkinson, travels through Central Asia and observes the medieval desiccation of the Aral Sea. He writes that ‘‘the water that serveth all to country is drawn by ditches out of the river Oxus [old name for Amudarya] into the great destruction of the said river, for which it falleth not into the Caspian Sea as it gath done in times past, and in short time all land is like to be destroyed, and to become a wilderness foe want of water when the river Oxus shall fail.’’ A. Jenkinson crosses the Ustyurt and visits Khiva and Bukhara, preparing a map of Central Asia. 1573 ‘‘Turn’’ of the Amudarya from the Sarykamysh to the Aral; in other words, the rather regular flow of part of its waters into the Sarykamysh ceases, the waters from this time running only to the Aral. 17th century 1627 In the book, ‘‘Knigi, glagolemoy Bolshoy Chertezh’’ (‘‘the big sketch’’), the Aral Sea is named ‘‘The dark blue sea.’’ 1670 German geographer Johann Goman publishes the map ‘‘Imperium pereicum,’’ on which the Aral is represented as a small lake located 10 German miles from the northeastern margin of the Caspian Sea. 1697 On Remezov’s map of the Aral Sea (more Aral’sko), it is for the first time represented as an internal lake completely separated from the Caspian Sea and into which the Amundarya (Amu Darya, Oxus), the Syrt (Syr Darya, Yaksart), and many small rivers flow.