MILTON BABBITT New World Records 80346

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BLACK, Pianist ROGER SESSIONS MIRIAM GIDEON

ROBERT BLACK, pianist Photo by Jane Hamborsky ROGER SESSIONS FIVE PIECES FOR PIANO (1974-75) ROGER SESSIONS (b. 1896, Brooklyn, New York) entered Harvard at the age of 14, and while there managed the footbal l team; he did graduate work with Horatio Parker at Yale. His subsequent studies, probably the most important to his development, were with Ernest Bloch. In his career as a composer and a teacher, Sessions has continued the 'great line' of European composers in its translation to the American musical community. Much of his early career was spent in Europe; after his return to this country, he profoundly influenced generations of students at Princeton, Berkeley and at Juilliard. The FIVE PIECES FOR PIANO were written in 1974 and 1975, thus coming between the cantata, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed , and the Ninth Symphony. In this ordered group, pieces I and V are linked by the slower tempo of their finely-worked counterpoint and their symmetrical forms and pro- cedures; II and IV share a brilliant agitato character and the scherzando, Ill, stands in the center. It was while writing piece IV, having completed the rest of the group, that Sessions heard of the death of a close friend and colleague. The brief tranquillo section which begins at the thirteenth bar marks this exact moment compositionally, and the entire group is inscribed "to the memory of Luigi Dallapiccola." - by Alan Fletcher MIRIAM GIDEON SONATA FOR PIANO (1977) MIRIAM GIDEON, born in Greeley, Colorado, has composed in all media. Her orchestral, chamber, and solo works have been performed and recorded in the U.S.A., Europe, and the Far East. -

Msm Camerata Nova

Saturday, March 6, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM JAMES LEE III A Narrow Pathway Traveled from Night Visions of Kippur (b. 1975) CHARLES WUORINEN New York Notes (1938–2020) (Fast) (Slow) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Chôros No. 7 (1887–1959) MAURICE RAVEL Introduction et Allegro (1875–1937) CAMERATA NOVA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA OBOE SAXOPHONE HARP Youjin Choi Sara Dudley Aaron Zhongyang Ling Minyoung Kwon New York, New York New York, New York Haettenschwiller Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Baltimore, Maryland VIOLIN 2 CELLO PERCUSSION PIANO Ally Cho Rei Otake CLARINET Arthur Seth Schultheis Melbourne, Australia Tokyo, Japan Ki-Deok Park Dhuique-Mayer Baltimore, Maryland Chicago, Illinois Champigny-Sur-Marne, France FLUTE Tarun Bellur Marcos Ruiz BASSOON Plano, Texas Miami, Florida Matthew Pauls Simi Valley, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

![Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6248/eric-dolphy-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-226248.webp)

Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Eric Dolphy Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu014006 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2014565637 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Eric Dolphy Collection Span Dates: 1939-1964 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1964) Call No.: ML31.D67 Creator: Dolphy, Eric Extent: Approximately 250 items ; 6 containers ; 5.0 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Eric Dolphy was an American jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and bass clarinetist. The collection consists of manuscript scores, sketches, parts, and lead sheets for works composed by Dolphy and others. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Dolphy, Eric--Manuscripts. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Works. Selections. Mingus, Charles, 1922-1979. Works. Selections. Schuller, Gunther. Works. Selections. Subjects Composers--United States. Jazz musicians--United States. Jazz--Lead sheets. Jazz. Music--Manuscripts--United States. Saxophonists--United States. Form/Genre Scores. Administrative Information Provenance Gift, James Newton, 2014. Accruals No further accruals are expected. Processing History The Eric Dolphy Collection was processed by Thomas Barrick in 2014. Thomas Barrick coded the finding aid for EAD format in October 2014. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Wuorinen Printable Program

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Celebrating Charles Wuorinen at 80 featuring Ensemble SIGNAL Brad Lubman, conductor Tuesday, April 24, 2018 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) iRidule Jacqueline Leclair, oboe soloist Spin 5 Olivia De Prato, violin soloist Intermission Megalith Eric Huebner, piano soloist PERSONNEL Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Music Director Paul Coleman, Sound Director Olivia De Prato, Violin Lauren Radnofsky, Cello Ken Thomson, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Adrián Sandí, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet David Friend, Piano 1 Oliver Hagen, Piano 2 Karl Larson, Piano 3 Georgia Mills, Piano 4 Matt Evans, Vibraphone, Piano Carson Moody, Marimba 1 Bill Solomon, Marimba 2 Amy Garapic, Marimba 3 Brad Lubman, Marimba Sarah Brailey, Voice 1 Mellissa Hughes, Voice 2 Kirsten Sollek, Voice 4 Charles Wuorinen In 1970 Wuorinen became the youngest composer at that time to win the Pulitzer Prize (for the electronic work Time's Encomium). The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way. Wuorinen has written more than 260 compositions to date. His most recent works include Sudden Changes for Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Exsultet (Praeconium Paschale) for Francisco Núñez and the Young People's Chorus of New York, a String Trio for the Goeyvaerts String Trio, and a duo for viola and percussion, Xenolith, for Lois Martin and Michael Truesdell. The premiere of of his opera on Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain was was a major cultural event worldwide. -

Washington State University Ninety-Second Annual Commencement

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY NINETY-SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT May 7, 1988 Appc,JrJncc of :,1 narnc on thh progr;.un i,r,; prcs"i.11nptivc evidence (Jf gr:,~du;,1tiun ancl gr:,ldu.:r.Hion houors .. bur if n1usr. no!. in ;u1y sense he n-·g~1rdcd :.i.s conclusive. Tl1c dip(oni;i {){" 1"l'lc un..i1 1 (::r:-iiry) !•;.igni:·d ;ind ~1c11Jc(] by ii:; proper i..>\\iccrs, reiT\~-lin,•~ ihc ()('fici;l.l tc·stirnuny of i 1·1e 1·ios-1;css!on of rh,-· c!cgrcc The Commencement Procession Order of Exercises Presiding-Dr. Samuel Smith, President Processional Candidates for Advanced Degrees Washington State University Wind Symphony Professor L. Keating Johnson, Conductor University Faculty Posting of the Colors Regents of the University Army ROTC Color Guard The National Anthem Honored Guests of the University Washington State University Wind Symphony Dr. Jane Wyss, Song Leader President of the University Invocation Reverend Graham Owen Hutchins Simpson United Methodist Church Introduction of Commencement Speaker Dr. Samuel Smith Commencement Address The Honorable Thomas S. Foley President's Faculty Excellence Awards Dr. Albert C. Yates Executive Vice President and Provost Instruction: Gerald L. Young Research: Linda L. Randall Public Service: Thomas L. Barton Festival March by Giacomo Puccini Washington State University Wind Symphony Bachelors Degrees Advanced Degrees Alma Mater The Assembly SPECIAL NOTE FOR PARENTS AND FRIENDS: Professional Recessional photographers will photograph all candidates as they receive their diploma covers from the deans at the all-university and Washington State University Wind Symphony college commencement ceremonies. A photo will be mailed to each graduate, and additional photos may be purchased at reasonable rates. -

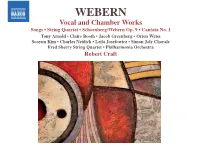

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance. -

Department of Music Programs 1983 - 1984 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 1984 Department of Music Programs 1983 - 1984 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1983 - 1984" (1984). School of Music: Performance Programs. 17. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/17 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATION WITH A CHRISTIAN PURPOSE Department of Music Programs 1983-1984 Olivet Hozarene College Kankakee, Illinois 60901 Telephone 815-939-5011 Olivet Nazarene College Artist Lecture Series presents GUEST RECITAL LOLA AUSTIN, P iano Fantasia in D Minor ...................................... W.A. Mozart (1756-1791) Andante Favori.................................... L. Van Beethoven (1770-1827) Sonata in C Major, Op. 5 3 ......................L. Van Beethoven "Waldstein" Movement 1. Allegro con brio Movement 2. Adagio Movement 3. Allegretto INTERMISSION Scherzo in B flat Minor Op. 3 1 ........................... F. Chopin (1810-1849) Nocturne in C sharp Minor Op. post ................... F. Chopin Three Etudes: A flat Major Op. 25, No. 1 ............. F. Chopin G. flat Major Op. 10, No. 5 C Minor Op. 25, No. 12 Fountains at the Villa d'este........................... Franz Liszt (1811-1886) L i t a n y .............................................. Schubert - Liszt Legende: St. Francis Walking on the Water ... -

Frank Mallory

Curriculum Vitae August 24, 2014 Frank B. Mallory W. Alton Jones Research Professor of Chemistry Bryn Mawr College, 101 N. Merion Avenue, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania 19010-2899 Phone: (610)-526-5105 Fax: (610)-526-5086 E-mail: [email protected] Undergraduate Education B.S. summa cum laude, Yale University, 1954 Chemistry major, mathematics minor Research with Professor Werner Bergmann Graduate Education Ph.D. California Institute of Technology, 1958 Chemistry major, physics minor, Dissertation research with Professor John D. Roberts Honors and Awards Phi Beta Kappa, Yale University, 1954 NSF Predoctoral Fellow, California Institute of Technology, 1954-1955 General Electric Company Fellow, California Institute of Technology, 1956-1957 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow, 1963-1964 Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow, 1964-1966 and 1966-1968 Bond Award of the American Oil Chemists' Society, 1970 NSF Senior Postdoctoral Fellow, 1970-1971 American Chemical Society Philadelphia Section Award for Distinguished Research, 1989 Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Foundation Award for Distinguished Teaching, 1992 Philadelphia Organic Chemists’ Club Award for Distinguished Research, 2000 Fellow of the Inter-American Photochemistry Society Award for Lifetime Achievements in and Contributions to the Photochemical Sciences, 2006 American Chemical Society Award as an ACS Fellow for contributions to science and the profession, 2014 Bryn Mawr College Appointments Assistant Professor of Chemistry, 1957-1963 Associate Professor of Chemistry, 1963-1969