Foundation Stones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

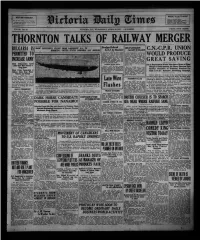

Thornton Talks of Railway Merger

WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT WEATHER FORECAST Coliseum—“Locked Doom." For 3C hours radio# 5 p.m., Thursday: Columbia—-•‘The Covered Wagon.” OomUiten Chance*” Victoria and Vtchiltr—Partly cloudy Playhouse—“Aad This I» London.- and eool, with ahawara. 4 — Capitol—“Gerald Cranston'» Lady.* == = VOL. 66 NO. 96 VICTORIA, B.C., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 22,1925 —16 PAGES. PRICE FIVE CENTS THORNTON TALKS OF RAILWAY MERGER Dredges Ordered MADE SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT FROM LAKEHURST, NJ., TO GREAT STURGEON BULGARIA IS BERMUDA; UNITED SÎATES DIRIGIBLE LOS ANGELES In VS. by Russians CAUGHT IN FRASER C.N.-C.P.R. UNION New York. April 21.—Fire repre New Westminster. April 22.—A sentatives of the Russian Soviet sturgeon, said to be one of the PERMITTED TO mining end machine construction largest ever caught In British Co WOULD PRODUCE Industries sailed for home to-day lumbia water*, wa* brought Into w after having placed an order for five thl* city yesterday. The fish, electric dredges with the Yuba weighing 1,015 pound* and Manufacturing Company of San measuring 12 feet « Inches In EREASEARMY :-/*■> Francisco. The machines, which will length, was caught by Patrick Ed GREAT SAVING jBy be valued at $1.200.000, will be used ward*. a fisherman, late Monday w In the ural platinum fields. night In a salmon gill net In the Allied Ambassadors Agree Fraser River a few miles below MISSION BOARD MEETS Mission City. Cut in Expenditures Would Take Care of Some of Fixed 7,000 More Men Needed to Toronto. April 22—The Foreign1 Charges of Both Systems, Sir Henry Thornton Tell» Keep Order Missions Board of the Presbyterian Men In Victoria with a long Church in Canada Is In session hero acquaintance with fishing say Railway Committee of Commons; President Up * -4i for what will be the last gathering of that twenty-five or thirty years Strict Press Censorship in the board before the consummation ago sturgeon weighing as much holds C. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Experiment in the Film

sh. eitedbyM&l MANVOX EXPERIMENT IN THE FILM edited by Roger Manveil In all walks of life experiment precedes and paves the way for practical and widespread development. The Film is no exception, yet although it must be considered one of the most popular forms of entertainment, very little is known by the general public about its experimental side. This book is a collec- tion of essays by the leading experts of all countries on the subject, and it is designed to give a picture of the growth and development of experiment in the Film. Dr. Roger Manvell, author of the Penguin book Film, has edited the collection and contributed a general appreciation. Jacket design by William Henry 15s. Od. net K 37417 NilesBlvd S532n 510-494-1411 Fremont CA 94536 www.nilesfilminiiseuin.org Scanned from the collections of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum Coordinated by the Media History Digital Library www.mediahistoryproject.org Funded by a donation from Jeff Joseph EDITED BY ROGER MANVELL THE GREY WALLS PRESS LTD First published in 1949 by the Grey Walls Press Limited 7 Crown Passage, Pall Mall, London S.W.I Printed in Great Britain by Balding & Mansell Limited London All rights reserved AUSTRALIA The Invincible Press Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide NEW ZEALAND The Invincible Press, Wellington SOUTH AFRICA M. Darling (Pty.) Ltd., Capetown EDITOR'S FOREWORD The aim of this book is quite simply to gather together the views of a number of people, prominent either in the field of film-making or film-criticism or in both, on the contribution of their country to the experimental development of the film. -

Autobiography of Lee De Forest

Father of Radio THE autobiography OF Lee de Forest r9fo WilcoxFollett Co. CHICAGO EDITORS: Linton J. Keith Arthur Brogue DESIGNER: Stanford W. Williamson COPYRIGHT, 1950, BY Wilcox & Follett Co. Chicago, Ill. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of the text may be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher, except brief quotations used in con- nection with reviews in magazines or newspapers. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Father of Radio I Dedication To my old comrades and associates in the forgotten days of Wireless -to my eager assistants in the early years of the Audion and of Radio- broadcasting-to the multitudes of young men and women who loved, as I have loved, the long night hours of listening to distant signals and far-off voices-to the keen engineers who hastened to grasp the new elec- tronic tools I laid before them, creating therewith a vast new universe- to the United States Navy, which was always prompt to use my new wireless and radio devices, whose operators heard my first radiobroadcast, and whose Admirals never failed to give me welcome encouragement when it was most sorely needed-to the United States Signal Corps, whose Chiefs and Officers have from the beginning continued to be friend and guide-to the Bell Laboratories engineers who first saw the worth of the Audion amplifier-to the radio announcers who must speak what is writ- ten though their hearts be not always therein-to the brilliant pioneers in our latest miracle of Television-to the partner of my earliest wireless ex- periments, E. -

LEST WE FORGET a Short History of Early Grand Valley, Colorado

LEST WE FORGET A short history of early Grand Valley, Colorado, originally called Parachute, Colorado. By Ewne 1JuJtJr.an:t MuJr.Jta.y First Edition Sk.e.tc.h.u by Connie Ann MuJr.Jta.Ij Copyright 1973 Printed by Quahada, Inc. All rights reserved Grand Junction, Colorado U.S.A. by Erlene Durrant Mlrray Chap1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Dedicated to The Parachute Pioneers o f • y\.1..1' VV'..r )1 Table of Contents Chapter Page • I Introduction to Parachute 1 2 Parachute Creek 7 3 Battlement Mesa 19 4 Wallace Creek 31 5 Morrisania Mesa 41 6 Rulison and Holmes Mesa 57 7 The Rai I road 66 8 Land, Water, &Range Rights 75 9 Schools 89 10 Churches 93 11 Firsts 101 12 Early Recreation 117 13 Crimes and Disasters 125 14 Mineral Wealth 141 15 Postscript 149 • • PREFACE This history is a project sponsored by and the product of the combined efforts of the members of the Home Culture Club of Grand Valley, organized in 1894, the oldest study and literary club in Garfield County. The members have generously contributed their time, memories, material and skills to this project; and I, a member of the club, have been privileged to do the research and assemble the facts and items I felt would be of general interest. I wish to thank the club for their confidence in me. It has been a wonderfully rewarding experience. The Home Culture Club and I wish to thank the pioneers them selves an~eir sons and daughters as well as the many others who so graciously have shared with us their memories of experiences and events related to them over the years. -

The Covered Wagon

The Covered Wagon US : 1923 : dir. James Cruze : Paramount Silent : 103 min† prod: : scr: Jack Cunningham : dir.ph.: Karl Brown Johnny Fox ………….………………………………………………………………………………… Lois Wilson; J. Warren Kerrigan; Ernest Torrence; Charles Ogle; Ethel Wales; Alan Hale Jr; Tully Marshall; Guy Oliver; Tim McCoy Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω Copy on VHS Last Viewed 2339a 3½ 10 2 1,667 - - - - - No unseen [† calculated at sound rate - 24 frames per second] Johnny Fox, centre, squares up to ornery Ernest Torrence. Charles Ogle and Alan Hale look on. Source: Silent Movies: A Picture Quiz Book Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide Speelfilm Encyclopedie review: 1996 review: “The first great Western epic cost around “Slow-paced silent forerunner of Western epics, $750,000, and the profit was about four following a wagon train as it combats indians million! The Western showed its power and and the elements; beautifully photographed, the genre began to be taken seriously. Jack but rather tame today. **½ ” Cunningham wrote the screenplay from the novel by Emerson Hough. The film revolves around the trek to California by two caravans California hills contained the glittering metal and their ordeals en route, such as indian that was to be a tremendous lure in 1849. attacks. The relationship between Wilson and Kerrigan is also shown. Hale wants Wilson too, This particular wagon train, which has some and tries to put Kerrigan out of the running in 300 vehicles, starts for Oregon. Through it all a a dirty way. Through this Wilson sees his true very pretty and simple love tale runs, as well as nature, and Kerrigan wins her over. -

Mam-XII Abstracts and Bios

Cleveland State University, School of Music International Musicological Society 12th Meeting of the IMS Study Group “Music and Media” Pre-Existing Music in Screen Media: Problems, Questions, Challenges Thursday, 10 June 2021 9:00–9:15 AM* Opening Remarks (CSU) w Professor Allyson L. Robichaud, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, CSU w Professor Emile Wennekes, Utrecht University, Chair of the Music and Media Study Group of the International Musicological Society 9:15–10:45 AM Panel 1: Redefining the Use of Pre-Existing Music through Bricolage (CSU) Chair: Emile Wennekes w Giorgio Biancorosso: “The Filmmaker as Music Bricoleur” Abstract: Whether as citation, hommage or allusion, the existing literature on film soundtracks examines the use of pre-existing music as a function of intertextuality. Spurred by the renewed interest surrounding the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, I propose that we rethink of at least certain soundtracks as a form of 'musical bricolage' instead. By combining already-existing music to striking imagery and novel dramatic situations, the filmmaker overwrites familiar associations and encourages new listening habits (above and beyond the circumstances of film listenership per se). To bear this out, I examine the musical nexus at the heart of the cinema of the Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar Wai. In crafting and subsequently marketing the soundtracks to his films, Wong channels a lifetime of chancing upon, listening to and collecting music in the commercial and artistic entrepôt of Hong Kong. Key to his musical borrowings are unobstructed access to global media, the circumstances of his films' production and reception, and penchant for 'poaching' music from other films (ranging from old Chinese melodramas to European art films). -

List of 7200 Lost US Silent Feature Films 1912-29

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 12/29/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – approximately 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) -

The Blue Book of Non-Theatrical Films

fit &/ue Sooii 7M Scanned from the collections of The Library of Congress AUDIO-VISUAL CONSERVATION at Vu- LIBRARY of CONGRESS mi Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation www. loc.gov/avconservation Motion Picture and Television Reading Room www.loc.gov/rr/mopic Recorded Sound Reference Center www.loc.gov/rr/record 100(W0NE (SEVENTH EDITION) JheBlueBook Tlondheatrical — 3ilmj THE EDUCATIONAL SCREEN CHICAGO NEWyORK. The Educational Screen, Inc. DIRECTORATE Herbert E. Slaught, President, Dudley Grant Hays, Chicago The University of Chicago. Schools. Stanley R. Greene, New York Frederick J. Lane, Treasurer, City. Chicago Schools. William R. Duffey, College of St. Thomas, St. Paul. Joseph J. Weber, Valparaiso Uni- Nelson L. Greene, Secretary and versity. Editor, Chicago. EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD A. W. Abrams, N. Y. State De- Dudley Grant Hays, Assistant partment of Education. Sup't. of Schools, Chicago. Richard Burton, University of Minnesota. P. Dean MoClusky, Scarborough Carlos E. Cummings, Buffalo So- School. ciety of Natural Sciences. Prank N. Freeman, The Univer- Rowland Rogers, Columbia Uni- sity of Chicago. versity. STAFF Nelson L. Greene, Editor, Marion F. Lanphier Evelyn J. Baker F. Dean MoClusky Marie E. Goodenough Stella Evelyn Myers Josephine F. Hoffman Marguerite Orndorff Publications of The Educational Screen The Educational Screen, (including Moving Picture Age and Visual Educa- I tion) now the only magazine in the field of visual education. Published j every month except July and August. Subscription price, $2.00 a year S ($3.00 for two years). In Canada, $2.50 ($4.00 for two years). Foreign J countries, $3.00 ($5.00 for two years). -

Native Americans and the Western: a History of Oppression

Global Tides Volume 13 Article 4 2019 Native Americans and the Western: A History of Oppression Haidyn Harvey Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/globaltides Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Harvey, Haidyn (2019) "Native Americans and the Western: A History of Oppression," Global Tides: Vol. 13 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/globaltides/vol13/iss1/4 This Humanities is brought to you for free and open access by the Seaver College at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global Tides by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Harvey: Native Americans and The Western: A History of Oppression 1 Native Americans and the Western: A History of Oppression by Haidyn Harvey The Western––it’s as American as apple pie. It’s a genre of nostalgia, adventure and the romanticized past. Always situated on the wide expanses and dusty horizons west of the Mississippi river, Westerns center around the do-it-yourself kind of justice carried out by bounty hunters, cowboys and even the lonely outlaw. The genre tells stories of the bravery and grit required to survive in the wild and uncivilized world just out of reach of the lawmakers back east. Most importantly, the Western is a genre of fear: fear of death, fear of the land and fear of fellow man. These overarching themes of paranoia coupled with expansive backdrops and historical settings make the Western the perfect canvas to explore race relations in America, both in the past and present. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 4, No. 1

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 4· NUMBER 1 SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE FAMILY AND CINEMA Editor's Note I Families, Film Genres, and Technological Environments 6 ANDREW ROSS Sons at the Brink of Manhood: Utopian Moments in Male Subjectivity 27 BILL NICHOLS The Role of Marriage in the Films of Yasujiro Ozu 44 KATHE GEIST Family, Education, and Postmodern Society: Yoshimitsu Morita's The Family Game 53 KEIKO I. McDONALD Was Tolstoy Right? Family Life and the Philippine Cinema ROBERT SILBERMAN Symbolic Representation and Symbolic Violence: Chinese Family Melodrama of the Early I980s 79 MA NING Fate and the Family Sedan II3 MEAGHAN MORRIS Domestic Scenes I35 PATRICIA MELLEN CAMP Book Review I68 DECEMBER 1989 The East-West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Editor's Note T HE CELEBRATED dramatist Eugene O'Neill once said that all drama takes place within the family. This is absolutely right; we can even expand this claim to include all forms of narrative. Fairy tales, ballads, the Bible, epics, the works of Sophocles and Shakespeare, soap operas, and the nov els of Tolstoy and Dickens in one way or another deal with the problems, tensions, and privations associated with the family. -

Microsoft Outlook

Robert Shields From: Jeff Rapsis <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, May 10, 2021 5:38 AM To: silentfilmmusic Subject: Saddle up and rediscover the Western with Town Hall Theatre summer silent film series Attachments: hells_hinges.jpg; salomy_jane.jpg; covered_wagon.jpg; go_west.jpg MONDAY, MAY 10, 2021 / FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jeff Rapsis • (603) 236-9237 • [email protected] Saddle up and rediscover the old West with Town Hall Theatre summer silent film series Roots of the Western revealed in a dozen rip-roaring and rarely screened silent features, all shown with live music WILTON, N.H.—It's a genre as old as the movies. It's the Western, and its origins will be explored in a summer-long series of rarely screened silent films at the Town Hall Theatre in Wilton, N.H. The series, which includes seven programs and a dozen movies, runs from early June through late August. The screenings are free to the public; a donation of $10 per person is suggested to support the Town Hall Theatre's silent film series. All programs will feature live music by silent film accompanist Jeff Rapsis. "Many of these films are over 100 years old, and so they're not far removed from the 'Old West' depicted in them," Rapsis said. The series ranges from big budget Hollywood epics such as 'The Covered Wagon'—the top grossing film of 1923—to obscure fare such as 'Salomy Jane' (1914), an early feature and the sole surviving film of the California Motion Picture Corp. Along the way, audiences will sample the stern morality of William S.