Native Americans and the Western: a History of Oppression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Wartrace Regulators

WARTRACE REGULATORS THE REGULATOR RECKONING 2017 Posse Assignments Main Match Dates: 10/12/2017 As of: 10/5/2017 Posse: 1 70529 Dobber TN Classic Cowboy 47357 Double Eagle Dave TN Silver Senior Duelist 27309 J.M. Brown NC Senior Duelist 1532 Joe West GA Frontiersman 101057 Lucky 13 OH Silver Senior 73292 Mortimer Smith TN Steam Punk 97693 Mustang Lewis TN Buckaroo 100294 News Carver AL Senior Duelist 42162 Noose KY Classic Cowboy 31751 Ocoee Red TN Silver Senior Posse Marshal 37992 Phiren Smoke IL Outlaw 106279 Pickpocket Kate TN Ladies Wrangler 96680 Scarlett Darlin' SC Ladies Gunfighter 76595 Sudden Sam TN Silver Senior Duelist 27625 T-Bone Angus TN B Western 5824 The Arizona Ranger MS Cattle Baron 60364 Tin Pot TN Elder Statesman Duelist 96324 Tyrel Cody TN Frontier Cartridge Gunfighter Total shooters on posse: 18 Posse: 1 WARTRACE REGULATORS THE REGULATOR RECKONING 2017 Posse Assignments Main Match Dates: 10/12/2017 As of: 10/5/2017 Posse: 2 52250 Bill Carson TN Frontier Cartridge Duelist 92634 Blackjack Lee AL B Western 104733 Boxx Carr Kid TN Young Guns Boy 31321 Captain Grouch KY Elder Statesman Duelist 103386 Cool Hand Stan TN Wrangler 94239 Dead Lee Shooter AL Gunfighter 55920 Deuce McCall TN Classic Cowboy 99358 Dr Slick TN Classic Cowgirl 20382 Georgia Slick TN Frontiersman 94206 Hot Lead Lefty TN Elder Statesman 69780 Perfecto Vaquera KY B Western Ladies 52251 Prestidigitator FL Cowboy 69779 Shaddai Vaquero KY Classic Cowboy Posse Marshal 77967 Slick's Sharp Shooter TN Cowgirl 97324 Tennessee Whiskers TN Classic Cowboy 32784 -

The Outlaw Hero As Transgressor in Popular Culture

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/10 Andreas J. Haller 75 The Outlaw Hero as Transgressor in Popular Culture Review of Thomas Hahn, ed. Robin Hood in Popular Culture: Violence, Trans- gression, and Justice. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. A look at the anthology Robin Hood in Popu- All articles in the anthology but one (by Sherron lar Culture, edited by Thomas Hahn, can give Lux) describe Robin Hood or his companions as some valuable insights into the role and func- heroes or heroic or refer to their heroism. Nei- tions of the hero in popular culture. The subtitle ther can we fi nd an elaborate theory of the pop- Violence, Transgression, and Justice shows the ular hero, nor are the models of heroism and direction of the inquiry. As the editor points out, heroization through popular culture made ex- since popular culture since the Middle Ages has plicit. Still, we can trace those theories and mo- been playful and transgressive, outlaw heroes dels which implicitly refer to the discourse of the are amongst the most popular fi gures, as they heroic. Therefore, I will paraphrase these texts “are in a categorical way, transgressors” (Hahn and depict how they treat the hero, heroization, 1). And Robin Hood is the most popular of them and heroism and how this is linked to the idea of all. Certainly, the hero is a transgressor in gen- transgression in popular culture. eral, not only the outlaw and not only in popular culture. Transgressiveness is a characteristic Frank Abbot recalls his work as a scriptwriter for trait of many different kinds of heroes. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl. -

{PDF EPUB} the Elephants by Georges Blond the Elephants by Georges Blond

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Elephants by Georges Blond The Elephants by Georges Blond. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6607bc654d604edf • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Sondra Locke: a charismatic performer defined by a toxic relationship with Clint Eastwood. S ondra Locke was an actor, producer, director and talented singer. But it was her destiny to be linked forever with Clint Eastwood, whose partner she was from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s. She was a sexy, charismatic performer with a tough, lean look who starred alongside Eastwood in hit movies like The Outlaw Josey Wales, The Gauntlet, Every Which Way But Loose (in which she sang her own songs — also for the sequel Any Which Way You Can) and Bronco Billy. But the pair became trapped in one of the most notoriously toxic relationships in Hollywood history, an ugly, messy and abusive overlap of the personal and professional — a case of love gone sour and mentorship gone terribly wrong. -

'Pale Rider' Is Clint Eastwood's First Western Film Since He Starred in and Directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976

'Pale Rider' is Clint Eastwood's first Western film since he starred in and directed "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in 1976. Eastwood plays a nameless stranger who rides into the gold rush town of LaHood, California and comes to the aid of a group of independent gold prospectors who are being threatened by the LaHood mining corporation. The independent miners hold claims to a region called Carbon Canyon, the last of the potentially ore-laden areas in the county. Coy LaHood wants to dredge Carbon Canyon and needs the independent miners out LaHood hires the county marshal, a gunman named Stockburn with six deputies, to get the job done. What neither LaHood nor Stockburn could possibly have taken into consideration is the appearance of the enigmatic horseman and the fate awaiting them. This study guide attempts to place 'Pale Rider' within the Western genre and also within the canon of Eastwood's films. We would suggest that the work on Film genre and advertising are completed before students see 'Pale Rider'. FILM GENRE The word "genre" might well be unfamiliar to you. It is a French word which means "type" and so when we talk of film genre we mean type of film. The western is one particular genre which we will be looking at in detail in this study guide. What other types of genre are there in film? Horror is one. Task One Write a list of all the different film genres that you can think of. When you have done this, try to write a list of genres that you might find in literature. -

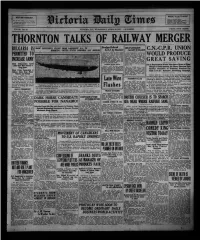

Thornton Talks of Railway Merger

WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT WEATHER FORECAST Coliseum—“Locked Doom." For 3C hours radio# 5 p.m., Thursday: Columbia—-•‘The Covered Wagon.” OomUiten Chance*” Victoria and Vtchiltr—Partly cloudy Playhouse—“Aad This I» London.- and eool, with ahawara. 4 — Capitol—“Gerald Cranston'» Lady.* == = VOL. 66 NO. 96 VICTORIA, B.C., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 22,1925 —16 PAGES. PRICE FIVE CENTS THORNTON TALKS OF RAILWAY MERGER Dredges Ordered MADE SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT FROM LAKEHURST, NJ., TO GREAT STURGEON BULGARIA IS BERMUDA; UNITED SÎATES DIRIGIBLE LOS ANGELES In VS. by Russians CAUGHT IN FRASER C.N.-C.P.R. UNION New York. April 21.—Fire repre New Westminster. April 22.—A sentatives of the Russian Soviet sturgeon, said to be one of the PERMITTED TO mining end machine construction largest ever caught In British Co WOULD PRODUCE Industries sailed for home to-day lumbia water*, wa* brought Into w after having placed an order for five thl* city yesterday. The fish, electric dredges with the Yuba weighing 1,015 pound* and Manufacturing Company of San measuring 12 feet « Inches In EREASEARMY :-/*■> Francisco. The machines, which will length, was caught by Patrick Ed GREAT SAVING jBy be valued at $1.200.000, will be used ward*. a fisherman, late Monday w In the ural platinum fields. night In a salmon gill net In the Allied Ambassadors Agree Fraser River a few miles below MISSION BOARD MEETS Mission City. Cut in Expenditures Would Take Care of Some of Fixed 7,000 More Men Needed to Toronto. April 22—The Foreign1 Charges of Both Systems, Sir Henry Thornton Tell» Keep Order Missions Board of the Presbyterian Men In Victoria with a long Church in Canada Is In session hero acquaintance with fishing say Railway Committee of Commons; President Up * -4i for what will be the last gathering of that twenty-five or thirty years Strict Press Censorship in the board before the consummation ago sturgeon weighing as much holds C. -

Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2021 Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979 Billy Loper Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Loper, Billy, "Paradoxes of the Heart and Mind: Three Case Studies in White Identity, Southern Reality, and the Silenced Memories of Mississippi Confederate Dissent, 1860-1979" (2021). Master's Theses. 825. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/825 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADOXES OF THE HEART AND MIND: THREE CASE STUDIES IN WHITE IDENTITY, SOUTHERN REALITY, AND THE SILENCED MEMORIES OF MISSISSIPPI CONFEDERATE DISSENT, 1860-1979 by Billy Don Loper A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Humanities at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Susannah J. Ural, Committee Chair Andrew P. Haley Rebecca Tuuri August 2021 COPYRIGHT BY Billy Don Loper 2021 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This thesis is meant to advance scholars understanding of the processes by which various groups silenced the memory of Civil War white dissent in Mississippi. -

Vaya Con Dios, Kemosabe: the Multilingual Space of Westerns from 1945 to 1976

https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7968.2020v40n2p282 VAYA CON DIOS, KEMOSABE: THE MULTILINGUAL SPACE OF WESTERNS FROM 1945 TO 1976 William F. Hanes1 1Pesquisador Autônomo, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Abstract: Since the mythic space of the Western helped shape how Americans view themselves, as well as how the world has viewed them, the characterization of Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo interaction warrants closer scrutiny. For a corpus with substantial diachrony, every Western in the National Registry of Films produced between the end of the Second World War and the American Bicentennial (1945-1976), i.e. the cultural apex of the genre, was assessed for the presence of foreign language and interpretation, the relationship between English and social power, and change over time. The analysis showed that although English was universally the language of power, and that the social status of characters could be measured by their fluency, there was a significant presence of foreign language, principally Spanish (63% of the films), with some form of interpretation occurring in half the films. Questions of cultural identity were associated with multilingualism and, although no diachronic pattern could be found in the distribution of foreign language, protagonism for Hispanics and Native Americans did grow over time. A spectrum of narrative/cinematic approaches to foreign language was determined that could be useful for further research on the presentation of foreigners and their language in the dramatic arts. Keywords: Westerns, Hollywood, Multilingualism, Cold War, Revisionism VAYA CON DIOS, KEMOSABE: O ESPAÇO MULTILINGUE DE FAROESTES AMERICANOS DE 1945 A 1976 Resumo: Considerando-se que o espaço mítico do Faroeste ajudou a dar forma ao modo como os norte-americanos veem a si mesmos, e também Esta obra utiliza uma licença Creative Commons CC BY: https://creativecommons.org/lice William F. -

The Role of Trickster Humor in Social Evolution William Gearty Murtha

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2013 The Role Of Trickster Humor In Social Evolution William Gearty Murtha Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Murtha, William Gearty, "The Role Of Trickster Humor In Social Evolution" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 1578. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1578 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF TRICKSTER HUMOR IN SOCIAL EVOLUTION by William Gearty Murtha Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2013 PERMISSION Title The Role of Trickster Humor in Social Evolution Department English Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in his absence, by the Chairperson of the department or his dean of the Graduate School. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this thesis or part thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Radar, Bikini Run Slated at Bent's Camp Feb. 14

NORTH WOODS TRADER Saturday, Feb. 14, 2015 Page 2 FEATURED RESTAURANT LODGE RESTAURANT On the Famous Cisco Chain of Lakes Radar, bikini run slated Bloody Mary Bar every Saturday and Sunday at Bent’s Camp Feb. 14 Nightly specials including Old-Fashioned Chicken Dinner • Prime Rib • Broasted Chicken Ribs & Wings • Homemade Pizzas This week’s featured Our House Specialty: Canadian Walleye served 7 different ways establishment is Bent’s Famous Friday Fish Fry & Fresh Salad Bar on Fridays! Camp Lodge Restaurant, located on the Cisco Chain of OPEN 6 DAYS A WEEK 11 A.M. TO CLOSE ~ CLOSED TUESDAYS Lakes in Land O’ Lakes. www.bents-camp.com The annual Radar Run (715) 547-3487 benefitting the Frosty Snow- 6882 Helen Creek Rd., 10 miles west of Land O’ Lakes on Cty. B mobile Club of Land O’ Lakes is set Saturday, Feb. 14, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. The bikini run will take place at Bent’s Camp at 3 p.m. Live music with Taylor Davis will begin at 4 p.m. There also will be an outdoor ice bar, food, raffles and more. Bent’s Camp, established in 1896, features cabin rentals, a bait shop, gift shop and a lodge restaurant with a full bar. Amy and Craig Kusick bought the business in April of 2011 with the goal of mak- ing Bent’s Camp a great place to visit year after year. Located on the Cisco Chain of Lakes, Bent’s Lake, a bar and restaurant, cabin rentals, bait The restaurant was built Camp offers impressive views of Mamie shop and gift shop.