The Outlaw Hero As Transgressor in Popular Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

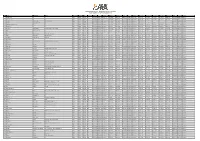

Outlaw Triathlon 2012 - Provisional Results: Version 4 Email Enquiries - [email protected]

OUTLAW TRIATHLON 2012 - PROVISIONAL RESULTS: VERSION 4 EMAIL ENQUIRIES - [email protected] POS NAME SURNAME CLUB RACE NO. GENDER CAT CAT POS. SWIM T1 BIKE SPLIT 1 BIKE SPLIT 2 BIKE SPLIT 3 BIKE T2 RUN SPLIT 1 RUN SPLIT 2 RUN SPLIT 3 RUN SPLIT 4 RUN SPLIT 5 RUN SPLIT 6 RUN FINISH NOTES 1 GI TRI CLUB 936 TEAM TEAM 1 00:57:09 00:01:06 00:26:14 02:35:55 03:31:17 04:28:33 00:00:17 00:21:44 01:39:31 01:17:59 01:39:31 02:18:32 02:42:00 03:23:07 08:50:14 Finished 2 THE SHERIFFS 977 TEAM TEAM 2 00:50:05 00:02:01 01:41:33 02:49:44 03:55:32 05:04:40 00:00:19 00:18:07 00:35:59 01:07:27 01:25:49 01:59:22 02:19:42 02:55:46 08:52:53 Finished 3 HARRY WILTSHIRE DRIVIN TO TRI 918 MALE 25/29 1 00:48:35 00:01:49 01:41:53 02:48:00 03:49:02 04:53:29 00:02:33 00:20:55 00:42:44 03:19:47 09:06:16 Finished 4 CHRIS GOODFELLOW 231 MALE 30/34 1 00:54:48 00:02:53 00:31:27 02:48:13 03:49:33 04:53:21 00:02:50 00:20:12 00:40:41 01:16:52 01:38:09 02:16:17 02:39:16 03:17:25 09:11:19 Finished 5 CANCER RESEARCH UK 929 TEAM TEAM 3 00:55:25 00:00:45 00:36:06 02:57:42 04:00:51 05:04:58 00:00:16 00:20:24 00:40:27 01:16:32 01:37:51 02:14:35 02:36:11 03:14:17 09:15:44 Finished 6 DAWN 2 934 TEAM TEAM 4 01:03:09 00:00:54 01:48:57 02:59:59 04:09:10 05:22:17 00:00:19 00:19:29 00:38:12 01:11:09 01:30:23 02:04:21 02:23:59 02:59:07 09:25:50 Finished 7 NATHAN BRADFORD CLIMB ON BIKES HEREFORD 205 MALE 30/34 2 00:59:28 00:02:00 00:32:17 02:56:08 03:58:13 05:02:49 00:02:02 00:21:26 00:42:11 01:19:17 01:40:12 02:18:22 02:41:09 03:19:39 09:26:01 Finished 8 JOHN WHITWORTH 304 MALE 30/34 -

March 2009 Newsletter

MARCH 2009 NEWSLETTER March Calendar of Events That's Science Fiction Tuesday March 3, 2009 7:00 pm - 9:00 pm Fantasy Gamers Group Hillsdale Public Library Saturday March 21, 2009 201.358.5072 2:30 pm - 7:30 pm Shadow of the Vampire (2000). Reality's Edge Game Store Seville Diner follows the movie - 289 Broadway, Westwood,NJ. Ridge Road North Arlington, NJ Suspense Central Explore the freaky world of HP Lovecraft's Cthulu mythos as writer, Monday March 9, 2009 gamer, and veteran GM BJ Pehush takes the reigns for a story of 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm gangland murders, strange beings, and terror beyond imagining as Borders @ Garden State Plaza we explore the town of Arkham. This game will use the 6th edition 201.712.1166 Call of Cthulu This month's selection is LAMB: The Gospel According to Bif, Chaosium rules (books available for order through New Moon Christs' Childhood Pal by Christopher Moore. Comics). Drawing A Crowd Themes of the Fantastic Wednesday March 11, 2009 Tuesday March 24, 2009 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm New Moon Comics New Moon Comics 973-81-COMIC or 973-812-6642 973-81-COMIC or 973-812-6642 Discussion group re: comic books. Topic discussion group www.newmooncomics.com. www.newmooncomics.com. Whispers from Beyond & Face the Fiction Modern Masters Saturday March 14, 2009 Friday March 27, 2009 7:00 pm - 8:00pm (Whispers From Beyond) 8:00pm - 10:00 pm 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm (Face The Fiction) Borders Ramsey Interstate Shopping Center Borders Ramsey Interstate Shopping Center 201.760.1967 201.760.1967 This month we discuss Christopher Moore's Bloodsucking This month's guest is bestselling horror writer, L.A. -

Volume 1, Issue 1 2017 ROBIN HOOD and the FOREST LAWS

Te Bulletin of the International Association for Robin Hood Studies Volume 1, Issue 1 2017 ROBIN HOOD AND THE FOREST LAWS Stephen Knight The University of Melbourne The routine opening for a Robin Hood film or novel shows a peasant being harassed for breaking the forest laws by the brutal, and usually Norman, authorities. Robin, noble in both social and behavioral senses, protects the peasant, and offends the authorities. So the hero takes to the forest with the faithful peasant for a life of manly companionship and liberal resistance, at least until King Richard returns and reinstates Robin for his loyalty to true values, social and royal, which are somehow congruent with his forest freedom. The story makes us moderns feel those values are age-old. But this is not the case. The modern default opening is not part of the early tradition. Its source appears to be the very well-known and influential Robin Hood and his Merry Men by Henry Gilbert (1912). The apparent lack of interest in the forest laws theme in the early ballads might simply be taken as reality: Barbara A. Hanawalt sees a strong fit between the early Robin Hood poems and contemporary outlaw actuality. Her detailed analysis of what outlaws actually did against the law indicates that robbery and assault were normal and that breach of the forest laws was never an issue.1 The forest laws themselves are certainly medieval.2 They were famously imposed by the Norman kings, they harassed ordinary people, stopping them using the forests for their animals and as a source for food and timber, and Sherwood was one of the most aggressively policed forests—but this did not cross into the early Robin Hood materials. -

Wartrace Regulators

WARTRACE REGULATORS THE REGULATOR RECKONING 2017 Posse Assignments Main Match Dates: 10/12/2017 As of: 10/5/2017 Posse: 1 70529 Dobber TN Classic Cowboy 47357 Double Eagle Dave TN Silver Senior Duelist 27309 J.M. Brown NC Senior Duelist 1532 Joe West GA Frontiersman 101057 Lucky 13 OH Silver Senior 73292 Mortimer Smith TN Steam Punk 97693 Mustang Lewis TN Buckaroo 100294 News Carver AL Senior Duelist 42162 Noose KY Classic Cowboy 31751 Ocoee Red TN Silver Senior Posse Marshal 37992 Phiren Smoke IL Outlaw 106279 Pickpocket Kate TN Ladies Wrangler 96680 Scarlett Darlin' SC Ladies Gunfighter 76595 Sudden Sam TN Silver Senior Duelist 27625 T-Bone Angus TN B Western 5824 The Arizona Ranger MS Cattle Baron 60364 Tin Pot TN Elder Statesman Duelist 96324 Tyrel Cody TN Frontier Cartridge Gunfighter Total shooters on posse: 18 Posse: 1 WARTRACE REGULATORS THE REGULATOR RECKONING 2017 Posse Assignments Main Match Dates: 10/12/2017 As of: 10/5/2017 Posse: 2 52250 Bill Carson TN Frontier Cartridge Duelist 92634 Blackjack Lee AL B Western 104733 Boxx Carr Kid TN Young Guns Boy 31321 Captain Grouch KY Elder Statesman Duelist 103386 Cool Hand Stan TN Wrangler 94239 Dead Lee Shooter AL Gunfighter 55920 Deuce McCall TN Classic Cowboy 99358 Dr Slick TN Classic Cowgirl 20382 Georgia Slick TN Frontiersman 94206 Hot Lead Lefty TN Elder Statesman 69780 Perfecto Vaquera KY B Western Ladies 52251 Prestidigitator FL Cowboy 69779 Shaddai Vaquero KY Classic Cowboy Posse Marshal 77967 Slick's Sharp Shooter TN Cowgirl 97324 Tennessee Whiskers TN Classic Cowboy 32784 -

Treacherous 'Saracens' and Integrated Muslims

TREACHEROUS ‘SARACENS’ AND INTEGRATED MUSLIMS: THE ISLAMIC OUTLAW IN ROBIN HOOD’S BAND AND THE RE-IMAGINING OF ENGLISH IDENTITY, 1800 TO THE PRESENT 1 ERIC MARTONE Stony Brook University [email protected] 53 In a recent Associated Press article on the impending decay of Sherwood Forest, a director of the conservancy forestry commission remarked, “If you ask someone to think of something typically English or British, they think of the Sherwood Forest and Robin Hood… They are part of our national identity” (Schuman 2007: 1). As this quote suggests, Robin Hood has become an integral component of what it means to be English. Yet the solidification of Robin Hood as a national symbol only dates from the 19 th century. The Robin Hood legend is an evolving narrative. Each generation has been free to appropriate Robin Hood for its own purposes and to graft elements of its contemporary society onto Robin’s medieval world. In this process, modern society has re-imagined the past to suit various needs. One of the needs for which Robin Hood has been re-imagined during late modern history has been the refashioning of English identity. What it means to be English has not been static, but rather in a constant state of revision during the past two centuries. Therefore, Robin Hood has been adjusted accordingly. Fictional narratives erase the incongruities through which national identity was formed into a linear and seemingly inevitable progression, thereby fashioning modern national consciousness. As social scientist Etiénne Balibar argues, the “formation of the nation thus appears as the fulfillment of a ‘project’ stretching over centuries, in which there are different stages and moments of coming to self-awareness” (1991: 86). -

Resource Guide the Adventures of Robin Hood

2019-2020 Theatre Season Heroes and Villains Blinn College Division of Visual/Performing Arts and Kinesiology Brenham Campus The Adventures of Robin Hood Resource Guide This resource guide serves as an educational starting point to understanding and enjoying Michele L. Vacca’s adaptation of The Adventures of Robin Hood. With this in mind, please note that the interpretations of the theatrical work may differ from the original source content. Performances November 21 & 22 7 p.m. November 23 & 24 2 p.m. Elementary School Preview Performances: November 21 & 22 10 a.m. & 1 p.m. Dr. W.W. O’Donnell Performing Arts Center Auditorium Brenham, Texas Tickets can be purchased in advance online at www.blinn.edu/BoxOffice, by calling 979-830-4024, or by emailing [email protected] Directed by Brad Nies Technical Theatre Direction by Kevin Patrick Costume, Makeup, and Hair Design by Jennifer Patrick KCACTF Entry The Adventures of Robin Hood is Blinn College-Brenham’s entry to the 2019 Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival. The aims of this national theater program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. Each production entered is eligible for a response by a KCACTF representative. Synopsis Based on the novel The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood by Howard Pyle, and adapted by Chicago playwright Michele L. Vacca, this play tells the story of a heroic outlaw who lives in Sherwood Forest and bestows generosity to the less fortunate. But when the nasty Sheriff of Nottingham forces the locals to pay unaffordable taxes, Robin fights against him by stealing from the rich so that he may give to the poor. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

The Chartist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’S Royston Gower; Or, the Days of King John (1838)

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 44 Article 8 Issue 2 Reworking Walter Scott 12-31-2019 The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838) Stephen Basdeo Richmond: the American International University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Basdeo, Stephen (2019) "The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838)," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 2, 72–81. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHARTIST ROBIN HOOD: THOMAS MILLER’S ROYSTON GOWER; OR, THE DAYS OF KING JOHN (1838) Stephen Basdeo Thomas Miller was born in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire in 1807, to a poor family and in his early youth worked as a ploughboy before becoming a shoemaker’s apprentice. He had a limited education, but his mother encouraged him to read on a daily basis.1 In his adult life, he became a professional author. He greatly admired Walter Scott, whom he referred to as “the immortal author of Waverley.”2 Indeed, such was his admiration that it was in emulation of Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) that Miller authored his own Robin Hood novel titled Royston Gower; or, The Days of King John, published in December 1838.3 Ivanhoe had a profound influence upon the Robin Hood legend. -

Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf

C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] ACTIVITIES C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] ROBIN HOOD 1. Who are these people? Explain who are the main characters of the story following the example: a) Richard the Lionheart: he was the king of England. He left to fight in the Crusades. b) Robin Hood: ____________________________________________________________ c) Marian: ____________________________________________________________ d) Prince John: ____________________________________________________________ e) The Sheriff: ____________________________________________________________ f) Guy of Gisborne: ____________________________________________________________ g) Richard of Verysdale: ____________________________________________________________ h) Little John: ____________________________________________________________ i) Friar Tuck: ____________________________________________________________ 2. Are these sentences true or false? Check it in the book and justify your answer: a) Prince John is a very good king to England. b) Richard leaves to fight in the Crusades because he doesn’t like being king. c) Robin and Marian want to marry. d) Little John is a very little man. e) The Sheriff wants to have Marian’s lands. f) Richard of Verysdale rents a boat that belongs to the Sheriff. C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] 3. Complete the sentences with the correct word from the box: a) Richard of Verysdale ___________that prince John was ___________Edward’s death. b) When prince John became king, he asked terrible Norman ___________to be his ___________. c) When Robin and Little John met in the middle of the ___________, Little John ___________Robin into the river. d) Guy of Gisborne ordered to ___________Much’s ___________. -

Remembering the Outlaw in Medieval England

Remembering the Outlaw in Medieval England The emergence of the Robin Hood legend Charles Robert Kos, B.Sc. (Melb), B.A. (Hons). Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Monash University, Australia. July 2014 Under the Copyright Act 1968, this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted from it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. I certify that I have made all reasonable efforts to secure copyright permissions for third- party content included in this thesis and have not knowingly added copyright content to my work without the owner's permission. Table of Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................... v Statement .................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... ix Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. xi Introduction .............................................................................................................. -

The Role of Trickster Humor in Social Evolution William Gearty Murtha

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2013 The Role Of Trickster Humor In Social Evolution William Gearty Murtha Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Murtha, William Gearty, "The Role Of Trickster Humor In Social Evolution" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 1578. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1578 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF TRICKSTER HUMOR IN SOCIAL EVOLUTION by William Gearty Murtha Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2013 PERMISSION Title The Role of Trickster Humor in Social Evolution Department English Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in his absence, by the Chairperson of the department or his dean of the Graduate School. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this thesis or part thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission.