Remembering the Outlaw in Medieval England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

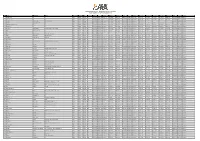

Outlaw Triathlon 2012 - Provisional Results: Version 4 Email Enquiries - [email protected]

OUTLAW TRIATHLON 2012 - PROVISIONAL RESULTS: VERSION 4 EMAIL ENQUIRIES - [email protected] POS NAME SURNAME CLUB RACE NO. GENDER CAT CAT POS. SWIM T1 BIKE SPLIT 1 BIKE SPLIT 2 BIKE SPLIT 3 BIKE T2 RUN SPLIT 1 RUN SPLIT 2 RUN SPLIT 3 RUN SPLIT 4 RUN SPLIT 5 RUN SPLIT 6 RUN FINISH NOTES 1 GI TRI CLUB 936 TEAM TEAM 1 00:57:09 00:01:06 00:26:14 02:35:55 03:31:17 04:28:33 00:00:17 00:21:44 01:39:31 01:17:59 01:39:31 02:18:32 02:42:00 03:23:07 08:50:14 Finished 2 THE SHERIFFS 977 TEAM TEAM 2 00:50:05 00:02:01 01:41:33 02:49:44 03:55:32 05:04:40 00:00:19 00:18:07 00:35:59 01:07:27 01:25:49 01:59:22 02:19:42 02:55:46 08:52:53 Finished 3 HARRY WILTSHIRE DRIVIN TO TRI 918 MALE 25/29 1 00:48:35 00:01:49 01:41:53 02:48:00 03:49:02 04:53:29 00:02:33 00:20:55 00:42:44 03:19:47 09:06:16 Finished 4 CHRIS GOODFELLOW 231 MALE 30/34 1 00:54:48 00:02:53 00:31:27 02:48:13 03:49:33 04:53:21 00:02:50 00:20:12 00:40:41 01:16:52 01:38:09 02:16:17 02:39:16 03:17:25 09:11:19 Finished 5 CANCER RESEARCH UK 929 TEAM TEAM 3 00:55:25 00:00:45 00:36:06 02:57:42 04:00:51 05:04:58 00:00:16 00:20:24 00:40:27 01:16:32 01:37:51 02:14:35 02:36:11 03:14:17 09:15:44 Finished 6 DAWN 2 934 TEAM TEAM 4 01:03:09 00:00:54 01:48:57 02:59:59 04:09:10 05:22:17 00:00:19 00:19:29 00:38:12 01:11:09 01:30:23 02:04:21 02:23:59 02:59:07 09:25:50 Finished 7 NATHAN BRADFORD CLIMB ON BIKES HEREFORD 205 MALE 30/34 2 00:59:28 00:02:00 00:32:17 02:56:08 03:58:13 05:02:49 00:02:02 00:21:26 00:42:11 01:19:17 01:40:12 02:18:22 02:41:09 03:19:39 09:26:01 Finished 8 JOHN WHITWORTH 304 MALE 30/34 -

Make We Merry More and Less

G MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS RAY MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature SELECTED AND INTRODUCED BY DOUGLAS GRAY EDITED BY JANE BLISS Conceived as a companion volume to the well-received Simple Forms: Essays on Medieval M English Popular Literature (2015), Make We Merry More and Less is a comprehensive anthology of popular medieval literature from the twel�h century onwards. Uniquely, the AKE book is divided by genre, allowing readers to make connec�ons between texts usually presented individually. W This anthology offers a frui�ul explora�on of the boundary between literary and popular culture, and showcases an impressive breadth of literature, including songs, drama, and E ballads. Familiar texts such as the visions of Margery Kempe and the Paston family le�ers M are featured alongside lesser-known works, o�en oral. This striking diversity extends to the language: the anthology includes Sco�sh literature and original transla�ons of La�n ERRY and French texts. The illumina�ng introduc�on offers essen�al informa�on that will enhance the reader’s enjoyment of the chosen texts. Each of the chapters is accompanied by a clear summary M explaining the par�cular delights of the literature selected and the ra�onale behind the choices made. An invaluable resource to gain an in-depth understanding of the culture ORE AND of the period, this is essen�al reading for any student or scholar of medieval English literature, and for anyone interested in folklore or popular material of the �me. -

The Outlaw Hero As Transgressor in Popular Culture

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/10 Andreas J. Haller 75 The Outlaw Hero as Transgressor in Popular Culture Review of Thomas Hahn, ed. Robin Hood in Popular Culture: Violence, Trans- gression, and Justice. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. A look at the anthology Robin Hood in Popu- All articles in the anthology but one (by Sherron lar Culture, edited by Thomas Hahn, can give Lux) describe Robin Hood or his companions as some valuable insights into the role and func- heroes or heroic or refer to their heroism. Nei- tions of the hero in popular culture. The subtitle ther can we fi nd an elaborate theory of the pop- Violence, Transgression, and Justice shows the ular hero, nor are the models of heroism and direction of the inquiry. As the editor points out, heroization through popular culture made ex- since popular culture since the Middle Ages has plicit. Still, we can trace those theories and mo- been playful and transgressive, outlaw heroes dels which implicitly refer to the discourse of the are amongst the most popular fi gures, as they heroic. Therefore, I will paraphrase these texts “are in a categorical way, transgressors” (Hahn and depict how they treat the hero, heroization, 1). And Robin Hood is the most popular of them and heroism and how this is linked to the idea of all. Certainly, the hero is a transgressor in gen- transgression in popular culture. eral, not only the outlaw and not only in popular culture. Transgressiveness is a characteristic Frank Abbot recalls his work as a scriptwriter for trait of many different kinds of heroes. -

Resource Guide the Adventures of Robin Hood

2019-2020 Theatre Season Heroes and Villains Blinn College Division of Visual/Performing Arts and Kinesiology Brenham Campus The Adventures of Robin Hood Resource Guide This resource guide serves as an educational starting point to understanding and enjoying Michele L. Vacca’s adaptation of The Adventures of Robin Hood. With this in mind, please note that the interpretations of the theatrical work may differ from the original source content. Performances November 21 & 22 7 p.m. November 23 & 24 2 p.m. Elementary School Preview Performances: November 21 & 22 10 a.m. & 1 p.m. Dr. W.W. O’Donnell Performing Arts Center Auditorium Brenham, Texas Tickets can be purchased in advance online at www.blinn.edu/BoxOffice, by calling 979-830-4024, or by emailing [email protected] Directed by Brad Nies Technical Theatre Direction by Kevin Patrick Costume, Makeup, and Hair Design by Jennifer Patrick KCACTF Entry The Adventures of Robin Hood is Blinn College-Brenham’s entry to the 2019 Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival. The aims of this national theater program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. Each production entered is eligible for a response by a KCACTF representative. Synopsis Based on the novel The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood by Howard Pyle, and adapted by Chicago playwright Michele L. Vacca, this play tells the story of a heroic outlaw who lives in Sherwood Forest and bestows generosity to the less fortunate. But when the nasty Sheriff of Nottingham forces the locals to pay unaffordable taxes, Robin fights against him by stealing from the rich so that he may give to the poor. -

The Chartist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’S Royston Gower; Or, the Days of King John (1838)

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 44 Article 8 Issue 2 Reworking Walter Scott 12-31-2019 The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838) Stephen Basdeo Richmond: the American International University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Basdeo, Stephen (2019) "The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838)," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 2, 72–81. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHARTIST ROBIN HOOD: THOMAS MILLER’S ROYSTON GOWER; OR, THE DAYS OF KING JOHN (1838) Stephen Basdeo Thomas Miller was born in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire in 1807, to a poor family and in his early youth worked as a ploughboy before becoming a shoemaker’s apprentice. He had a limited education, but his mother encouraged him to read on a daily basis.1 In his adult life, he became a professional author. He greatly admired Walter Scott, whom he referred to as “the immortal author of Waverley.”2 Indeed, such was his admiration that it was in emulation of Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) that Miller authored his own Robin Hood novel titled Royston Gower; or, The Days of King John, published in December 1838.3 Ivanhoe had a profound influence upon the Robin Hood legend. -

Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf

C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] ACTIVITIES C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] ROBIN HOOD 1. Who are these people? Explain who are the main characters of the story following the example: a) Richard the Lionheart: he was the king of England. He left to fight in the Crusades. b) Robin Hood: ____________________________________________________________ c) Marian: ____________________________________________________________ d) Prince John: ____________________________________________________________ e) The Sheriff: ____________________________________________________________ f) Guy of Gisborne: ____________________________________________________________ g) Richard of Verysdale: ____________________________________________________________ h) Little John: ____________________________________________________________ i) Friar Tuck: ____________________________________________________________ 2. Are these sentences true or false? Check it in the book and justify your answer: a) Prince John is a very good king to England. b) Richard leaves to fight in the Crusades because he doesn’t like being king. c) Robin and Marian want to marry. d) Little John is a very little man. e) The Sheriff wants to have Marian’s lands. f) Richard of Verysdale rents a boat that belongs to the Sheriff. C/ San Antonio, 22 21800 Moguer (Huelva) Robin Hood | Ángela Torronteras Moreno Telf. 959 371 677 [email protected] 3. Complete the sentences with the correct word from the box: a) Richard of Verysdale ___________that prince John was ___________Edward’s death. b) When prince John became king, he asked terrible Norman ___________to be his ___________. c) When Robin and Little John met in the middle of the ___________, Little John ___________Robin into the river. d) Guy of Gisborne ordered to ___________Much’s ___________. -

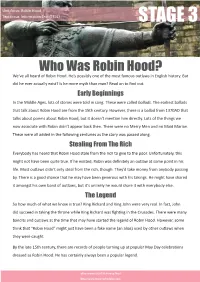

Robin Hood Text Focus: Information Text (750L) STAGE 3

Unit focus: Robin Hood Text focus: Information Text (750L) STAGE 3 Who Was Robin Hood? We’ve all heard of Robin Hood. He’s possibly one of the most famous outlaws in English history. But did he ever actually exist? Is he more myth than man? Read on to fi nd out. Early Beginnings In the Middle Ages, lots of stories were told in song. These were called ballads. The earliest ballads that talk about Robin Hood are from the 15th century. However, there is a ballad from 1370AD that talks about poems about Robin Hood, but it doesn’t menti on him directly. Lots of the things we now associate with Robin didn’t appear back then. There were no Merry Men and no Maid Marian. These were all added in the following centuries as the story was passed along. Stealing From The Rich Everybody has heard that Robin Hood stole from the rich to give to the poor. Unfortunately, this might not have been quite true. If he existed, Robin was defi nitely an outlaw at some point in his life. Most outlaws didn’t only steal from the rich, though. They’d take money from anybody passing by. There is a good chance that he may have been generous with his takings. He might have shared it amongst his own band of outlaws, but it’s unlikely he would share it with everybody else. The Legend So how much of what we know is true? King Richard and King John were very real. In fact, John did succeed in taking the throne while King Richard was fi ghti ng in the Crusades. -

Basdeo, S (2017) Robin Hood the Brute: Representations of the Outlaw in 18Th-Century Criminal Biography

Citation: Basdeo, S (2017) Robin Hood the Brute: Representations of the Outlaw in 18th-Century Criminal Biography. Law, Crime & History, 6 (2). pp. 54-70. ISSN 2045-9238 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/4514/ Document Version: Article (Published Version) Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Law, Crime and History (2016) 2 ROBIN HOOD THE BRUTE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE OUTLAW IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CRIMINAL BIOGRAPHY Stephen Basdeo1 Abstract Eighteenth century criminal biography is a topic that has been explored at length by both crime historians such as Andrea McKenzie and Richard Ward, as well as literary scholars such as Lincoln B. -

Frequency List

Ranking Frequency List 3501 1) 23903 (4.19%) 27) 3221 (0.564%) 53) 1589 (0.278%) 78) 1054 (0.185%) 103) 694 (0.122%) the is out we some 2) 20303 (3.56%) 28) 3201 (0.561%) 54) 1582 (0.277%) 79) 1046 (0.183%) 104) 689 (0.121%) And as down Nor mother 3) 12989 (2.27%) 29) 3008 (0.527%) 55) 1574 (0.276%) 80) 1019 (0.178%) 105) 685 (0.120%) to him What no here 4) 11511 (2.02%) 30) 2996 (0.525%) 56) 1560 (0.273%) 81) 1014 (0.178%) 106) 679 (0.119%) a will see bonny nae 5) 10028 (1.76%) 31) 2492 (0.436%) 57) 1545 (0.271%) 82) 1009 (0.177%) 107) 665 (0.116%) I Then If father take 6) 9557 (1.67%) 32) 2265 (0.397%) 58) 1509 (0.264%) 83) 989 (0.173%) 108) 662 (0.116%) he at man thy gae 7) 8855 (1.55%) 33) 2234 (0.391%) my with 59) 1482 (0.260%) 84) 984 (0.172%) 109) 660 (0.116%) I’ll never like 8) 6968 (1.22%) 34) 2224 (0.389%) in there 60) 1468 (0.257%) 85) 956 (0.167%) 110) 657 (0.115%) them are from 9) 6746 (1.18%) 35) 2215 (0.388%) green O lady 61) 1439 (0.252%) 86) 937 (0.164%) has men 111) 649 (0.114%) 10) 6260 (1.10%) 36) 2178 (0.381%) She’s her this 62) 1436 (0.251%) 87) 933 (0.163%) fair He’s 112) 646 (0.113%) 11) 6071 (1.06%) 37) 2112 (0.370%) yon that come 63) 1431 (0.251%) 88) 924 (0.162%) were dear 113) 644 (0.113%) 12) 5893 (1.03%) 38) 2092 (0.366%) been me by 64) 1374 (0.241%) 89) 912 (0.160%) now well 114) 623 (0.109%) 13) 5642 (0.988%) 39) 2011 (0.352%) It’s his wi 65) 1330 (0.233%) 90) 884 (0.155%) shall one 115) 622 (0.109%) 14) 5640 (0.988%) 40) 1896 (0.332%) get for all 66) 1326 (0.232%) 91) 869 (0.152%) gold so hand made 15) -

Teacher's Guide to the Core Classics Edition of Robin Hood

Teacher’s Guide to The Core Classics Edition of Robin Hood By Judy Gardner Copyright 2003 Core Knowledge Foundation This online edition is provided as a free resource for the benefit of Core Knowledge teachers and others using the Core Classics edition of Robin Hood. This edition is retold from Old Ballads by J. Walker McSpadden. Resale of these pages is strictly prohibited. Publisher’s Note We are happy to make available this Teacher’s Guide to the Core Classics version of Robin Hood and His Merry Outlaws prepared by Judy Gardner. We are presenting it and other guides in an electronic format so that they are accessible to as many teachers as possible. Core Knowledge does not endorse any one method of teaching a text; in fact we encourage the creativity involved in a diversity of approaches. At the same time, we want to help teachers share ideas about what works in the classroom. In this spirit we invite you to use any or all of the ways Judy Gardner has found to make this book enjoyable and understandable to fourth grade students. We hope that you find the background material, which is addressed specifically to teachers, useful preparation for teaching the book. We also hope that the vocabulary and grammar exercises designed for students will help you integrate the reading of literature with the development of skills in language arts. Most of all, we hope this guide helps to make Robin Hood a marvelous adventure in reading for both you and your students. 2 Contents Publisher’s Note ................................................................................................................... -

Local Legends, Places and Walks Within 2.5 Miles of Kings Clipstone

Robin of Sherwood "Lythe and listin, gentilmen, That be of frebore blode; I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode." -A Gest of Robyn Hode Local legends, places and walks within 2.5 miles of Kings Clipstone Includes maps of the local path network and Sherwood Pines Forest Park The Robin Hood legends may be just story telling, but they are still important historically because they were the popular culture of the late mediaeval period. In 1377 the first written reference was made to rhymes about Robin that already existed. Outlaws were just that, outside the law and its protection; they could be hunted by anyone. According to different versions Robin had been a yeoman, a knight and an earl before becoming an outlaw. Walter Bower, a chronicler in the early 1400’s, calls Robin a “cut-throat”. By the 1460’s Robin and his band are said to have “infested Sherwood and other law-abiding areas of England with continuous robberies.” In the early tales Robin's main targets were not the ruling classes, but figures of medieval corruption, like bishops, abbots and the sheriff. It was the mediaeval ‘May Games’ that turned Robin into a mythological figure. At the May Games, Robin was often portrayed as the King of the May or Summer King, leading the procession. King ‘Robin’ and his followers from the town or church would go to another community and collect money. Perhaps the church gave the money collected to the poor, giving rise to the tales of that Robin and his merry men robbing ‘from the rich to give to the poor’.