Introduction in the United States Today the Mention of Trailers and Mobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 66–75 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2391 Article “Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks Margarethe Kusenbach Department of Sociology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 1 August 2019 | Accepted: 4 October 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract In the United States, residents of mobile homes and mobile home communities are faced with cultural stigmatization regarding their places of living. While common, the “trailer trash” stigma, an example of both housing and neighbor- hood/territorial stigma, has been understudied in contemporary research. Through a range of discursive strategies, many subgroups within this larger population manage to successfully distance themselves from the stigma and thereby render it inconsequential (Kusenbach, 2009). But what about those residents—typically white, poor, and occasionally lacking in stability—who do not have the necessary resources to accomplish this? This article examines three typical responses by low-income mobile home residents—here called resisting, downplaying, and perpetuating—leading to different outcomes regarding residents’ sense of community belonging. The article is based on the analysis of over 150 qualitative interviews with mobile home park residents conducted in West Central Florida between 2005 and 2010. Keywords belonging; Florida; housing; identity; mobile homes; stigmatization; territorial stigma Issue This article is part of the issue “New Research on Housing and Territorial Stigma” edited by Margarethe Kusenbach (University of South Florida, USA) and Peer Smets (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands). © 2020 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

Mobile Home - Wikipedia

9/10/2020 Mobile home - Wikipedia Mobile home A mobile home (also trailer, trailer home, house trailer, static caravan, residential caravan or simply caravan) is a prefabricated structure, built in a factory on a permanently attached chassis before being transported to site (either by being towed or on a trailer). Used as permanent homes, or for holiday or temporary accommodation, they are left often permanently or semi- permanently in one place, but can be moved, and may be required to move from time to time for legal reasons. Mobile homes share the same historic origins as travel trailers, but today the two are very different in size and furnishings, with travel Typical mobile home from the late 1960s and early 1970s: 12 by 60 trailers being used primarily as temporary or vacation homes. feet (3.6 × 18.3 m) Behind the cosmetic work fitted at installation to hide the base, there are strong trailer frames, axles, wheels, and tow-hitches. Contents History Manufactured home Construction and sizes Regulations 1958 photo of Zimmer trailer in a United States trailer park in Tampa Florida, this Cleveland, Mississippi area is now a gated community with North Carolina new houses Mobile home parks By country United Kingdom Israel Difference from modular homes Gallery See also References Further reading External links History https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobile_home 1/10 9/10/2020 Mobile home - Wikipedia In the United States, this form of housing goes back to the early years of cars and motorized highway travel.[1] It was derived from the travel trailer (often referred to during the early years as "house trailers" or "trailer coaches"), a small unit with wheels attached permanently, often used for camping or extended travel. -

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration July 2017 Harris Beider, Stacy Harwood, Kusminder Chahal Acknowledgments We thank all research participants for your enthusiastic participation in this project. We owe much gratitude to our two fabulous research assistants, Rachael Wilson and Erika McLitus from the University of Illinois, who helped us code all the transcripts, and to Efadul Huq, also from the University of Illinois, for the design and layout of the final report. Thank you to Open Society Foundations, US Programs for funding this study. About the Authors Harris Beider is Professor in Community Cohesion at Coventry University and a Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Stacy Anne Harwood is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Kusminder Chahal is a Research Associate for the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. For more information Contact Dr. Harris Beider Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations Coventry University, Priory Street Coventry, UK, CV1 5FB email: [email protected] Dr. Stacy Anne Harwood Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 111 Temple Buell Hall, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive Champaign, IL, USA, 61820 email: [email protected] How to Cite this Report Beider, H., Harwood, S., & Chahal, K. (2017). “The Other America”: White working-class views on belonging, change, identity, and immigration. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University, UK. ISBN: 978-1-84600-077-5 Photography credits: except when noted all photographs were taken by the authors of this report. -

Mobile Home and Manufactured Housing Parks

CHAPTER XI. MOBILE HOME AND MANUFACTURED HOUSING PARKS Article 1. Mobile Home and Manufactured Housing Parks ______________________________________________________________ ARTICLE 1. MOBILE HOME AND MANUFACTURED HOUSING PARKS 11-101 DEFINITIONS. As used in this Chapter: (A) Manufactured Home means a structure which: (1) Is transportable in one or more sections which, in the traveling mode, is 8 body feet or more in width or 40 body feet or more in length, or, when erected on site, is 320 or more square feet, and which is built on a permanent chassis and designed to be used as a dwelling, with or without permanent foundation, when connected to the required utilities, and includes plumbing, heating, air conditioning and electrical systems contained therein; and (2) Is subject to the federal manufactured home construction and safety standards established pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Section 5403. (B) Mobile Home means a structure which: (1) Is transportable in one or more sections which, in the traveling mode, is 8 body feet or more in width or 28 body feet or more in length, and is built on a permanent chassis and designed to be used as a dwelling, with or without a permanent foundation, when connected to the required utilities, and includes the plumbing, heating, air conditioning and electrical systems contained therein; and (2) Is not subject to the federal manufactured home construction and safety standards established pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Section 5403. (C) Manufactured Home and Mobile Home Park or Park means any lot upon which are located one or more manufactured homes or mobile homes, occupied for dwelling purposes, regardless of whether or not a charge is made for each accommodation. -

Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 10 December 2007 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation López, A. (2017). Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/ 10.31390/taboo.11.1.10 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterAntonio López 2007 73 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them. ... To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies—all this is indispensably necessary. Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth. —George Orwell, 19841 I will speak to you in plain, simple English. And that brings us to tonight’s word: ‘truthiness.’ Now I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s are gonna say, ‘hey, that’s not really a word.’ Well, anyone who knows me knows I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. -

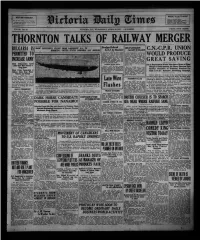

Thornton Talks of Railway Merger

WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT WEATHER FORECAST Coliseum—“Locked Doom." For 3C hours radio# 5 p.m., Thursday: Columbia—-•‘The Covered Wagon.” OomUiten Chance*” Victoria and Vtchiltr—Partly cloudy Playhouse—“Aad This I» London.- and eool, with ahawara. 4 — Capitol—“Gerald Cranston'» Lady.* == = VOL. 66 NO. 96 VICTORIA, B.C., WEDNESDAY, APRIL 22,1925 —16 PAGES. PRICE FIVE CENTS THORNTON TALKS OF RAILWAY MERGER Dredges Ordered MADE SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT FROM LAKEHURST, NJ., TO GREAT STURGEON BULGARIA IS BERMUDA; UNITED SÎATES DIRIGIBLE LOS ANGELES In VS. by Russians CAUGHT IN FRASER C.N.-C.P.R. UNION New York. April 21.—Fire repre New Westminster. April 22.—A sentatives of the Russian Soviet sturgeon, said to be one of the PERMITTED TO mining end machine construction largest ever caught In British Co WOULD PRODUCE Industries sailed for home to-day lumbia water*, wa* brought Into w after having placed an order for five thl* city yesterday. The fish, electric dredges with the Yuba weighing 1,015 pound* and Manufacturing Company of San measuring 12 feet « Inches In EREASEARMY :-/*■> Francisco. The machines, which will length, was caught by Patrick Ed GREAT SAVING jBy be valued at $1.200.000, will be used ward*. a fisherman, late Monday w In the ural platinum fields. night In a salmon gill net In the Allied Ambassadors Agree Fraser River a few miles below MISSION BOARD MEETS Mission City. Cut in Expenditures Would Take Care of Some of Fixed 7,000 More Men Needed to Toronto. April 22—The Foreign1 Charges of Both Systems, Sir Henry Thornton Tell» Keep Order Missions Board of the Presbyterian Men In Victoria with a long Church in Canada Is In session hero acquaintance with fishing say Railway Committee of Commons; President Up * -4i for what will be the last gathering of that twenty-five or thirty years Strict Press Censorship in the board before the consummation ago sturgeon weighing as much holds C. -

Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990S Literary and Pop Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2018 Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture Eli W. Bromberg University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bromberg, Eli W., "Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1156. https://doi.org/10.7275/11176350.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1156 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by ELI WOLF BROMBERG Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2018 Department of English Concentration: American Studies © Copyright by Eli Bromberg 2018 All Rights Reserved SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented By ELI W. BROMBERG -

Challenges Faced by Mobile Home Owners

Mobile homes are an important source of housing for older Americans. As the cost of housing has increased, mobile homes present a seemingly affordable alternative to elders in need of housing. Approximately 41% of mobile homes occupied as a primary residence are owned or rented by persons age 50 or older. Compared to owners of conventional single-family housing, a much higher proportion of mobile home owners over age 50 are low-income. Mobile homes are popular with older Americans because they are usually more affordable than conventional homes. The cost of a mobile home may be up to a third less than a similar home built on site. The homes are built in a factory, and then transported to the site where they will be installed. Once delivered, the home is anchored to the site. Despite their name, the homes are not very mobile as dismantling them and moving them can be difficult and expensive. Mobile homes are also known as manufactured homes. The term manufactured home is also sometimes used to describe modular homes. The regulation of the modular home industry differs significantly from the regulation of mobile homes. Challenges Faced by Mobile Home Owners Despite the popularity of mobile homes, owners face a wide range of problems. Consumers can run into trouble with the financing, the set-up, and the quality of the construction of mobile homes. Many have problems obtaining service under warranty. Mobile home owners who rent the land on which the home is placed confront additional challenges. The most common problems mobile home owners face generally fall into one of four categories. -

Sounds Gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH KEN BURNS AND HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. SUBJECT: RACE IN AMERICA MODERATOR: THOMAS BURR, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: THE PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2016 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THOMAS BURR: (Sounds gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Thomas Burr. I'm the Washington correspondent for the Salt Lake Tribune, and the 109th President of the National Press Club. Our guests today are documentarian Ken Burns and Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. I would like to welcome our C-SPAN and Public Radio audiences. And I want to remind you, you can follow the action on Twitter using the hashtag NPClive. That's NPClive. Now it’s time to introduce our head table guests. I'd ask that each of you stand briefly as your name is announced. Please hold your applause until I have finished introducing the entire table. From your right, Michael Fletcher, senior writer for ESPN’s “The Undefeated,” and the moderator of today’s luncheon. Bruce Johnson, anchor at WUSA, Channel 9; Jeff Ballou, Vice President of the National Press Club and news editor at Al Jazeera English; Sharon Rockefeller, a guest of our speakers and President and CEO of WETA; Elisabeth Bumiller, Washington bureau chief of the New York Times. -

Manufactured Housing

Manufactured Housing By Doug Ryan, Senior Director of home in 2017 was $71,900 (excluding land Affordable Homeownership, Prosperity costs); much less compared to an average Now of $293,727 for a newly constructed single- family home and approximately $184, 647 anufactured homes are an often for an existing site-built home (see the U.S. overlooked and maligned component Census Bureau’s Manufactured Homes Survey and of our nation’s housing stock, but these Characteristics of New Housing, along with the Mhomes are an important source of housing for National Association of Realtors’ Median Sales millions of Americans, especially those with low Price of Existing Homes). Manufactured homes incomes and in rural areas. Although the physical cost about half of what site-built homes cost per quality of manufactured housing continues to square foot, though transportation and onsite progress, the basic delivery system of how these work slightly increase the final costs. Even homes are sold, financed, and managed is still in though the purchase price of manufactured need of improvement to ensure that they are a homes can be relatively affordable, financing viable and quality source of affordable housing. them may not. The majority of manufactured homes are still financed with personal property, ISSUE SUMMARY or Chattel loans (see the Consumer Financial There are approximately 6.7 million occupied Protection Bureau’s Manufactured Housing manufactured homes in the U.S., comprising Consumer-Finance in the United States). With about 6% of the nation’s housing stock. More shorter terms and higher interest rates, personal than half of all manufactured homes are property loans are generally less beneficial located in rural areas around the country. -

Community in Property: Lessons from Tiny Homes Villages

COMMUNITY IN PROPERTY: LESSONS FROM TINY HOMES VILLAGES Lisa T. Alexander* The evolving role of community in property law remains undertheorized. While legal scholars have analyzed the commons, common interest communities, and aspects of the sharing economy, the recent rise of intentional co-housing communities remains relatively understudied. This Article provides a case study of tiny homes villages for the homeless and unhoused, as examples of communities that highlight the growing importance of flexibility and community in contemporary property law. These communities develop new housing tenures and property relationships that challenge the predominance of individualized, exclusionary, long-term, fee simple-ownership in contemporary property law. The villages, therefore, demonstrate property theories that challenge the hegemony of ownership in property law, such as progressive property theory, property as personhood theory, access versus ownership theories, stewardship, and urban commons theories in action. The property forms and relationships these villages create not only ameliorate homelessness, but also illustrate how communal relationships can provide more stability than ownership during times of uncertainty. Due to increasing natural disasters and other unpredictable phenomena, municipalities may find these property forms adaptable and, therefore, useful in mitigating increasing housing insecurity and instability. This case study also provides examples of successful stakeholder collaboration between groups that often conflict in urban redevelopment. These insights reveal a new role for community in property law, and are instructive for American governance and property law and theory. *Copyright © 2019 by Lisa T. Alexander, Professor of Law, Texas A&M University School of Law, with Joint Appointment in Texas A&M University’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning. -

A Resource at Risk: the Twin Cities Manufactured Housing in 2015

METROSTATS Exploring regional issues that matter June 2016 A Resource At Risk: The Twin Cities Region's Manufactured Housing in 2015 Key findings Manufactured homes—factory-made dwelling units built on permanent chassis (transportable frames)—made up 1.3% of all housing units in the Twin Cities region in 2015. Manufactured housing is an important and often overlooked affordable housing asset in the Twin Cities region: nearly 39,000 residents, most of whom have low incomes, live in manufactures homes in the region's manufactured home parks. Every year since 1975 we have surveyed manufactured home parks in the Twin Cities region to develop data on the number of spaces (pads), the number of manufactured homes, and the parks' occupancy trends. This Metro- Stats uses our survey and federal data sources to provide a snapshot of manufactured housing in the Twin Cities region today and the development trends that may affect its future. Our How many Twin Cities residents live Are development trends affecting How do manufactured home parks focus in manufactured home parks? manufactured home parks in the expand housing options? region? Our In 2015, nearly 39,000 residents lived Over the past 25 years, the region has Manufactured housing is an affordable findings in manufactured home parks across seen a steady loss of manufactured option for low-income residents and the Twin Cities region, about as many home parks: no new parks have been enables homeownership for economi- people as live in the City of Maple- built since 1991, but 10 have closed cally disadvantaged families. wood. in this period.