The Curious Institution of Mobile Home Rent Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Home - Wikipedia

9/10/2020 Mobile home - Wikipedia Mobile home A mobile home (also trailer, trailer home, house trailer, static caravan, residential caravan or simply caravan) is a prefabricated structure, built in a factory on a permanently attached chassis before being transported to site (either by being towed or on a trailer). Used as permanent homes, or for holiday or temporary accommodation, they are left often permanently or semi- permanently in one place, but can be moved, and may be required to move from time to time for legal reasons. Mobile homes share the same historic origins as travel trailers, but today the two are very different in size and furnishings, with travel Typical mobile home from the late 1960s and early 1970s: 12 by 60 trailers being used primarily as temporary or vacation homes. feet (3.6 × 18.3 m) Behind the cosmetic work fitted at installation to hide the base, there are strong trailer frames, axles, wheels, and tow-hitches. Contents History Manufactured home Construction and sizes Regulations 1958 photo of Zimmer trailer in a United States trailer park in Tampa Florida, this Cleveland, Mississippi area is now a gated community with North Carolina new houses Mobile home parks By country United Kingdom Israel Difference from modular homes Gallery See also References Further reading External links History https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobile_home 1/10 9/10/2020 Mobile home - Wikipedia In the United States, this form of housing goes back to the early years of cars and motorized highway travel.[1] It was derived from the travel trailer (often referred to during the early years as "house trailers" or "trailer coaches"), a small unit with wheels attached permanently, often used for camping or extended travel. -

Mobile Home and Manufactured Housing Parks

CHAPTER XI. MOBILE HOME AND MANUFACTURED HOUSING PARKS Article 1. Mobile Home and Manufactured Housing Parks ______________________________________________________________ ARTICLE 1. MOBILE HOME AND MANUFACTURED HOUSING PARKS 11-101 DEFINITIONS. As used in this Chapter: (A) Manufactured Home means a structure which: (1) Is transportable in one or more sections which, in the traveling mode, is 8 body feet or more in width or 40 body feet or more in length, or, when erected on site, is 320 or more square feet, and which is built on a permanent chassis and designed to be used as a dwelling, with or without permanent foundation, when connected to the required utilities, and includes plumbing, heating, air conditioning and electrical systems contained therein; and (2) Is subject to the federal manufactured home construction and safety standards established pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Section 5403. (B) Mobile Home means a structure which: (1) Is transportable in one or more sections which, in the traveling mode, is 8 body feet or more in width or 28 body feet or more in length, and is built on a permanent chassis and designed to be used as a dwelling, with or without a permanent foundation, when connected to the required utilities, and includes the plumbing, heating, air conditioning and electrical systems contained therein; and (2) Is not subject to the federal manufactured home construction and safety standards established pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Section 5403. (C) Manufactured Home and Mobile Home Park or Park means any lot upon which are located one or more manufactured homes or mobile homes, occupied for dwelling purposes, regardless of whether or not a charge is made for each accommodation. -

Challenges Faced by Mobile Home Owners

Mobile homes are an important source of housing for older Americans. As the cost of housing has increased, mobile homes present a seemingly affordable alternative to elders in need of housing. Approximately 41% of mobile homes occupied as a primary residence are owned or rented by persons age 50 or older. Compared to owners of conventional single-family housing, a much higher proportion of mobile home owners over age 50 are low-income. Mobile homes are popular with older Americans because they are usually more affordable than conventional homes. The cost of a mobile home may be up to a third less than a similar home built on site. The homes are built in a factory, and then transported to the site where they will be installed. Once delivered, the home is anchored to the site. Despite their name, the homes are not very mobile as dismantling them and moving them can be difficult and expensive. Mobile homes are also known as manufactured homes. The term manufactured home is also sometimes used to describe modular homes. The regulation of the modular home industry differs significantly from the regulation of mobile homes. Challenges Faced by Mobile Home Owners Despite the popularity of mobile homes, owners face a wide range of problems. Consumers can run into trouble with the financing, the set-up, and the quality of the construction of mobile homes. Many have problems obtaining service under warranty. Mobile home owners who rent the land on which the home is placed confront additional challenges. The most common problems mobile home owners face generally fall into one of four categories. -

Manufactured Housing

Manufactured Housing By Doug Ryan, Senior Director of home in 2017 was $71,900 (excluding land Affordable Homeownership, Prosperity costs); much less compared to an average Now of $293,727 for a newly constructed single- family home and approximately $184, 647 anufactured homes are an often for an existing site-built home (see the U.S. overlooked and maligned component Census Bureau’s Manufactured Homes Survey and of our nation’s housing stock, but these Characteristics of New Housing, along with the Mhomes are an important source of housing for National Association of Realtors’ Median Sales millions of Americans, especially those with low Price of Existing Homes). Manufactured homes incomes and in rural areas. Although the physical cost about half of what site-built homes cost per quality of manufactured housing continues to square foot, though transportation and onsite progress, the basic delivery system of how these work slightly increase the final costs. Even homes are sold, financed, and managed is still in though the purchase price of manufactured need of improvement to ensure that they are a homes can be relatively affordable, financing viable and quality source of affordable housing. them may not. The majority of manufactured homes are still financed with personal property, ISSUE SUMMARY or Chattel loans (see the Consumer Financial There are approximately 6.7 million occupied Protection Bureau’s Manufactured Housing manufactured homes in the U.S., comprising Consumer-Finance in the United States). With about 6% of the nation’s housing stock. More shorter terms and higher interest rates, personal than half of all manufactured homes are property loans are generally less beneficial located in rural areas around the country. -

Community in Property: Lessons from Tiny Homes Villages

COMMUNITY IN PROPERTY: LESSONS FROM TINY HOMES VILLAGES Lisa T. Alexander* The evolving role of community in property law remains undertheorized. While legal scholars have analyzed the commons, common interest communities, and aspects of the sharing economy, the recent rise of intentional co-housing communities remains relatively understudied. This Article provides a case study of tiny homes villages for the homeless and unhoused, as examples of communities that highlight the growing importance of flexibility and community in contemporary property law. These communities develop new housing tenures and property relationships that challenge the predominance of individualized, exclusionary, long-term, fee simple-ownership in contemporary property law. The villages, therefore, demonstrate property theories that challenge the hegemony of ownership in property law, such as progressive property theory, property as personhood theory, access versus ownership theories, stewardship, and urban commons theories in action. The property forms and relationships these villages create not only ameliorate homelessness, but also illustrate how communal relationships can provide more stability than ownership during times of uncertainty. Due to increasing natural disasters and other unpredictable phenomena, municipalities may find these property forms adaptable and, therefore, useful in mitigating increasing housing insecurity and instability. This case study also provides examples of successful stakeholder collaboration between groups that often conflict in urban redevelopment. These insights reveal a new role for community in property law, and are instructive for American governance and property law and theory. *Copyright © 2019 by Lisa T. Alexander, Professor of Law, Texas A&M University School of Law, with Joint Appointment in Texas A&M University’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning. -

A Resource at Risk: the Twin Cities Manufactured Housing in 2015

METROSTATS Exploring regional issues that matter June 2016 A Resource At Risk: The Twin Cities Region's Manufactured Housing in 2015 Key findings Manufactured homes—factory-made dwelling units built on permanent chassis (transportable frames)—made up 1.3% of all housing units in the Twin Cities region in 2015. Manufactured housing is an important and often overlooked affordable housing asset in the Twin Cities region: nearly 39,000 residents, most of whom have low incomes, live in manufactures homes in the region's manufactured home parks. Every year since 1975 we have surveyed manufactured home parks in the Twin Cities region to develop data on the number of spaces (pads), the number of manufactured homes, and the parks' occupancy trends. This Metro- Stats uses our survey and federal data sources to provide a snapshot of manufactured housing in the Twin Cities region today and the development trends that may affect its future. Our How many Twin Cities residents live Are development trends affecting How do manufactured home parks focus in manufactured home parks? manufactured home parks in the expand housing options? region? Our In 2015, nearly 39,000 residents lived Over the past 25 years, the region has Manufactured housing is an affordable findings in manufactured home parks across seen a steady loss of manufactured option for low-income residents and the Twin Cities region, about as many home parks: no new parks have been enables homeownership for economi- people as live in the City of Maple- built since 1991, but 10 have closed cally disadvantaged families. wood. in this period. -

Landlord and Tenant Chapter 953 Regulation of Mobile

MRS Title 10, Chapter 953. REGULATION OF MOBILE HOME PARKS; LANDLORD AND TENANT CHAPTER 953 REGULATION OF MOBILE HOME PARKS; LANDLORD AND TENANT §9091. Definitions As used in this chapter, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the following meanings. [PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §2 and Pt (AMD).] 1. Mobile home. "Mobile home" means a structure, transportable in one or more sections, which: A. Is 8 body feet or more in width and 32 body feet or more in length; [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §1 and Pt (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] B. Is built on a permanent chassis; [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §1 and Pt (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] C. Is designed to be used as a dwelling with or without a permanent foundation when connected to the required utilities; and [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §1 and Pt (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] D. Includes the plumbing, heating, air- conditioning and electrical systems contained in the structure. [PL 1987, c. 737, Pt. C, §1 and Pt (NEW); PL 1989, c. 6 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 9, §2 (AMD); PL 1989, c. 104, Pt. C, §§8, 10 (AMD).] [PL 1987, c. -

Manufactured Housing Communities Understanding the Conditions, Challenges, and Opportunities

An Assessment of Central Virginia’s Manufactured Housing Communities Understanding the Conditions, Challenges, and Opportunities November 2016 Prepared for project:HOMES An Assessment of Central Virginia’s Manufactured Housing Communities An Assessment of Central Virginia’s Manufactured Housing Communities Contents Introduction 1. Introduction n The Origins of This Report 1 n project:HOMES and the Mobile Home Park Coalition n Report Outline n History and Terminology The Origins of This Report n A Note on Nomenclature n the summer of 2014, local news outlets began covering the deteriorating 2. Regional Profile of Manufactured Home Residents conditions within one of the City of Richmond’s most overlooked communities: n Study Area Rudd’s Trailer Park. Situated along Jefferson Davis Highway in South Richmond, n Socio-Economic Characteristics of Central Virginia’s Manufactured Housing I Rudd’s garnered increasing attention after City inspectors initiated a code enforcement campaign that left many of the park’s mobile home units in serious 3. Regional Mobile Home Park Survey violation, or in some cases, outright condemned. n Field Survey Rationale and Methodology n Summary of Results Although the inadequate and often hazardous conditions of the older n Analysis of Trends mobile homes in Rudd’s were indisputable, community advocates raised concerns n Park Typologies about the now uncertain future for the park’s primarily low-income, Latino population. Unable to afford the necessary improvements to their homes, many of 4. Policy Analysis these families faced eviction and sudden homelessness. Rudd’s Trailer Park in the City of Richmond n Federal and Virginia Regulations The ongoing situation at Rudd’s revealed a troublesome disparity between n Financing and Assessment n Local Zoning and Land Use the demand for affordable housing and the need for safe, stable housing. -

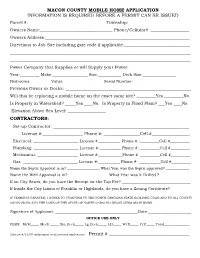

Mobile Home Application Information Is Required Before a Permit Can Be Issued

MACON COUNTY MOBILE HOME APPLICATION INFORMATION IS REQUIRED BEFORE A PERMIT CAN BE ISSUED Parcel #:_____________________________________Township:_____________________________ Owners Name:__________________________________ Phone/Cellular# :__________________ Owners Address:____________________________________________________________________ Directions to Job Site including gate code if applicable:_______________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ Power Company that Supplies or will Supply your Power: ____________________________ Year:__________ Make:__________________ Size:____________ Deck Size:_________________ Bedrooms: __________Value:____________________ Serial Number: _________________________ Previous Owner or Dealer: ___________________________________________________________ Will this be replacing a mobile home on the exact same site? _________Yes _________No Is Property in Watershed? _____Yes ____No. Is Property in Flood Plain? ___Yes ____No Elevation Above Sea Level: __________________ CONTRACTORS: Set-up Contractor: ________________________________________________________________ License #:___________________ Phone #: _________________Cell #__________________ Electrical: _______________________ License #:___________ Phone #: __________Cell #__________ Plumbing: _______________________ License #:___________ Phone #: __________Cell #__________ Mechanical: _____________________ -

The Florida Mobile Home Act, Is a Chapter of Law That Governs the Rental Or Leasing of Mobile Home Lots in the State of Florida

Department of Business CHAPTER 723 and FLORIDA STATUTES Professional Regulation THE FLORIDA MOBILE HOME ACT Division of Florida Condominiums, Timeshares, And and Chapters 61B-29 through 33 and 35, Mobile Homes Florida Administrative Code 2601 Blair Stone Rd Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1030 Includes laws enacted through the 2016 Legislative Session NOTICE TO RECIPIENT Chapter 723 of the Florida Statutes, also known as the Florida Mobile Home Act, is a chapter of law that governs the rental or leasing of mobile home lots in the State of Florida. The Florida Mobile Home Act should be read in conjunction with Chapters 61B- 29 through 33, and 35, Florida Administrative Code. These administrative rules are promulgated by the Division of Florida Condominiums, Timeshares, and Mobile Homes to interpret, enforce, and implement Chapter 723, Florida Statutes. Due to periodic changes to the statute and administrative rules, readers should inquire periodically to ensure that they are referring to the most recently revised copy. Division of Florida Condominiums, Timeshares, and Mobile Homes 2601 Blair Stone Road Tallahassee, FL 32399-1030 (850) 488-1122 This publication was undertaken expressly for the convenience of those who frequently refer to the Florida Statutes and Florida Administrative Code, and is not in any way intended to be an official published version of these laws and rules. F.S. 2016 MOBILE HOME PARK LOT TENANCIES Ch. 723 CHAPTER 723 MOBILE HOME PARK LOT TENANCIES 723.001 Short title. 723.056 Enforcement of right of assembly and right 723.002 Application of chapter. to hear outside speakers. 723.003 Definitions. 723.058 Restrictions on sale of mobile homes. -

Manufactured Housing As a Community-And Asset-Building Strategy

An Examination of Manufactured Housing as a Community-and Asset-Building Strategy Report to the Ford Foundation An Examination of Manufactured Housing as a Community- and Asset-Building Strategy Report to the Ford Foundation by Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation In collaboration with the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University William Apgar, Joint Center for Housing Studies Allegra Calder, Joint Center for Housing Studies Michael Collins, Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation Mark Duda, Joint Center for Housing Studies September 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT OF FINDINGS . i IV. MODEL COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES . 20 INTRODUCTION . 1 Replacement of Aging Manufactured Units . 20 Better Housing for Tompkins County . 20 I. MANUFACTURED HOUSING CONTINUES North Country Affordable Housing . 20 TO EVOLVE . 2 Rehabilitation of Aging Manufactured Units . 21 What is “Manufactured Housing”? . 2 Colorado Rural Housing Development Manufactured Housing’s Role in Housing Corporation . 21 Markets . 3 Cooperative Park Ownership . 21 The Organization of the Manufactured-Housing The New Hampshire Community Loan Fund . 22 Industry . 3 Developing Affordable Housing with Manufacturing and Transport . 4 Manufactured Units . 23 Retail Sales and Finance . 4 Noji Gardens . 23 Installation . 5 Barrington Project . 24 Placement . 5 Characteristics of the Manufactured-Housing V. OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES FOR Stock . 5 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT . 25 Geographic Distribution . 5 Industry Advocates . 25 Land-Use Restrictions . 6 Skeptics . 26 Improving Quality and Design . 7 Antagonists . 26 Land Tenure and Appreciation . 7 Role for Community-Development Entities . 26 Affordable Rental Housing . 9 Persistent Issues of Concern . 27 Changing Demographic Characteristics of Finance . 27 Manufactured-Home Owners . 9 Repossessions . 27 Household Income . 9 Retailers . 27 Age Structure . -

Accessing Public Resources for Homes and Communities

MANUFACTURED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE Accessing Public Resources for Homes and Communities BACKGROUND Each year millions of Americans realize the dream of home ownership with the purchase of a Table of Contents manufactured home. The low cost and good quality Federal Resources for Homes 2 of today’s manufactured homes lowers barriers to ownership for many consumers who cannot afford Formula or Block Grants 3 site-built homes. For these reasons, manufactured Project-based Grants 6 housing is now a significent source of unsubsidized affordable housing in the nation. The homes are Loan & Loan Guarantee Programs 7 an especially important source of housing in rural areas where distance and other logistical challenges State Resources for Homes 9 make it expensive to build new homes. Public Resources for Communities 10 Financing Challenges Facing Manufactured Conclusion & Recommendations 14 Housing Appendix A: Selected State Programs 18 Despite the popularity of manufactured homes, consumers struggle to find fair and affordable Appendix B: Additional Housing Resources 26 financing. A limited pool of lenders offers loans on manufactured homes. Given the nature of manufactured homes, most offer personal property loans with comparatively higher interest rates, shorter loan terms and fewer consumer protections than the conventional mortgage loans offered on site-built homes. Conventional financing, if available, is often limited to those who install their homes on permanent foundations on land they own. Moreover, consumers who place their home in land-lease communities, even those who own the land cooperatively, are at a distinct disadvantage to traditional homebuyers when seeking financing. Similarly, affordable housing developers must struggle to find financing when planning manufactured housing projects.