Trailer Park Boys, Adorno, and Trash Aesthetics a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pour Travelers: Dela... Where? - Part 2

The Pour Travelers: Dela...where? - Part 1 More Create Blog Sign In The Pour Travelers The Pour Travelers follows two craft beer enthusiasts and their monkey on excursions throughout their home state of PA as well as vacations to beer destinations across the country and beyond. Pages Friday, January 10, 2020 The Pour Travelers Ffej's Band Performance Dela...where? - Part 1 Schedule Looks like we're coming out of the gate swinging as we commence with 2020! The first weekend of the year, and we're already headed down the ol' Pour Travelers About Me trail. After a quick three-day detox from a beer-and-liquor-soaked New Year's Eve ffejherb (and Brewslut's birthday party), we're back at it, doin' what we do. We had originally planned to check out some new places in Philadelphia on this particular weekend, The skinny: Born March 26, but we decided to switch gears and try Delaware on for size. Despite being one of 1974 in Shamokin, PA. the nation's smallest states and next door neighbors to PA, we hadn't spent much Graduated from Shamokin time in "The First State." Save for a few visits to the Dogfish Head brewpub in Area High School in 1992. Graduated from Penn State Rehoboth Beach, Delaware was largely uncharted waters for us Pour Travelers. So it in 1996. Married my best was settled. We were off to Delaware. friend, Brandi, in 1999. Played in a zillion different I got up bright and early on Saturday morning after a good night's sleep and prepared bands (most notably Solar a healthy breakfast of scrambled eggs, home fries, and turkey bacon. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Student Bankruptcy Mystery

THE I SSUE The university of Winnipeg student weekly 202006/03/02 VOLUME 60 INSIDE 02 News 06 Comments 10 Diversions 12 Features uniter.ca 13 Arts & Culture » 19 Listings 22 Sports ON THE WEB [email protected] » E-MAIL SSUE 20 I VOL. 60 2006 02, H C R A M RESTORE THE ‘4’! 02 UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG STUDENTS PROTEST AGAINST TUITION FEE INCREASES STUDENT BANKRUPTCY 12 THE PROCESS, THE CONSEQUENCES, AND THE REALITY OF CLAIMING BANKRUPTCY INNIPEG STUDENTINNIPEG WEEKLY W MYSTERY, CONTRADICTION, AMBIGUITY 13 ORIGAMI AND PHOTO MONTAGES DAZZLE CROWD AT PLUG IN BISON COOK-OFF 22 Wesmen women’s b-ball team defeaT BISONS, ADVANCE TO FINAL FOUR HE UNIVERSITY OF T ♼ March 2, 2006 The Uniter contact: [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR: LEIGHTON KLASSEN NEWS EDITOR: DEREK LESCHASIN 02 NEWS E-MAIL: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] UNITER STAFF Day of Action Challenges the Feds to Ante Up WHITNEY LIGHT PHOTO: VIVIAN BELLIC Managing Editor » Jo Snyder BEAT REPORTER 01 [email protected] 02 Business Coordinator & Offi ce Manager » James D. Patterson [email protected] “ estore the 4!” was the chant NEWS PRODUCTION EDITOR » that carried through the 03 Derek Leschasin [email protected] R2006 Day of Action protest against tuition fee increases, held 04 SENIOR EDITOR » Leighton Klassen [email protected] Tuesday, Feb. 21 at the U of W Quad. Despite brisk temperatures, 50 to 60 05 BEAT REPORTER » Whitney Light [email protected] students and some faculty gathered BEAT REPORTER » Alan MacKenzie for dodge ball, a BBQ, and to urge 06 [email protected] the federal government to action on A HANDFUL OF STUDENTS RALLY IN THE QUAD TO SUPPORT THE TUITION FREEZE FEBRUARY 21. -

Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 66–75 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2391 Article “Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks Margarethe Kusenbach Department of Sociology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 1 August 2019 | Accepted: 4 October 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract In the United States, residents of mobile homes and mobile home communities are faced with cultural stigmatization regarding their places of living. While common, the “trailer trash” stigma, an example of both housing and neighbor- hood/territorial stigma, has been understudied in contemporary research. Through a range of discursive strategies, many subgroups within this larger population manage to successfully distance themselves from the stigma and thereby render it inconsequential (Kusenbach, 2009). But what about those residents—typically white, poor, and occasionally lacking in stability—who do not have the necessary resources to accomplish this? This article examines three typical responses by low-income mobile home residents—here called resisting, downplaying, and perpetuating—leading to different outcomes regarding residents’ sense of community belonging. The article is based on the analysis of over 150 qualitative interviews with mobile home park residents conducted in West Central Florida between 2005 and 2010. Keywords belonging; Florida; housing; identity; mobile homes; stigmatization; territorial stigma Issue This article is part of the issue “New Research on Housing and Territorial Stigma” edited by Margarethe Kusenbach (University of South Florida, USA) and Peer Smets (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands). © 2020 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration July 2017 Harris Beider, Stacy Harwood, Kusminder Chahal Acknowledgments We thank all research participants for your enthusiastic participation in this project. We owe much gratitude to our two fabulous research assistants, Rachael Wilson and Erika McLitus from the University of Illinois, who helped us code all the transcripts, and to Efadul Huq, also from the University of Illinois, for the design and layout of the final report. Thank you to Open Society Foundations, US Programs for funding this study. About the Authors Harris Beider is Professor in Community Cohesion at Coventry University and a Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Stacy Anne Harwood is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Kusminder Chahal is a Research Associate for the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. For more information Contact Dr. Harris Beider Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations Coventry University, Priory Street Coventry, UK, CV1 5FB email: [email protected] Dr. Stacy Anne Harwood Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 111 Temple Buell Hall, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive Champaign, IL, USA, 61820 email: [email protected] How to Cite this Report Beider, H., Harwood, S., & Chahal, K. (2017). “The Other America”: White working-class views on belonging, change, identity, and immigration. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University, UK. ISBN: 978-1-84600-077-5 Photography credits: except when noted all photographs were taken by the authors of this report. -

Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 10 December 2007 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation López, A. (2017). Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/ 10.31390/taboo.11.1.10 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterAntonio López 2007 73 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them. ... To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies—all this is indispensably necessary. Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth. —George Orwell, 19841 I will speak to you in plain, simple English. And that brings us to tonight’s word: ‘truthiness.’ Now I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s are gonna say, ‘hey, that’s not really a word.’ Well, anyone who knows me knows I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. -

Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990S Literary and Pop Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2018 Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture Eli W. Bromberg University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bromberg, Eli W., "Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1156. https://doi.org/10.7275/11176350.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1156 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by ELI WOLF BROMBERG Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2018 Department of English Concentration: American Studies © Copyright by Eli Bromberg 2018 All Rights Reserved SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented By ELI W. BROMBERG -

Parrot Analytics

The Global Television Demand Report Q2 2019 Copyright © 2019 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. The Global Television Demand Report Global SVOD platform demand share, digital original series popularity and genre demand share trends in Q2 2019 Copyright © 2019 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. | Demand Expressions®: The total audience demand being expressed for a title, within a country, on any platform. The Global Television Demand Report Q2 2019 Copyright © 2019 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Executive Summary April – June, 2019 • In the second quarter of 2019 Netflix remains the clear global market- leading platform based on demand for original productions. • The service has captured 62.6% of all demand for digital original series in over 100 markets analysed for this report, down 3.1% from its Q1 result of 64.6%. • We speculate that Netflix’s global demand share trend will likely reverse in the third quarter due to the global impact of Stranger Things season 3. • The number of competitors offering original series is growing and this is being reflected in the fragmentation of consumer attention: 10.3% of the global share of demand is for originals from smaller, specialist and local SVODs. This is 2.5% more than in the first quarter of 2019. • In the action/adventure genre of four markets, DC Universe Originals have more demand share than Netflix Originals. However, Netflix Originals still dominate the important drama genre. • This quarter’s most demanded subgenre is sci-fi drama, which was the largest subgenre in five markets. Superhero series was a clear second for markets in this report, with crime drama and comedy drama also in Stranger Things Lucifer Star Trek: Discovery Black Mirror demand across all ten markets. -

The Trailer Park Boys “Still Drunk, High and Unemployed Tour” Brings the Streaming Comedy Show to Parker Playhouse

October 12, 2016 Media Contact: Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954-776-1999 ext. 225 Jan Goodheart, Broward Center 954-765-5814 THE TRAILER PARK BOYS “STILL DRUNK, HIGH AND UNEMPLOYED TOUR” BRINGS THE STREAMING COMEDY SHOW TO PARKER PLAYHOUSE FORT LAUDERDALE – In a night of zany comedy about the misadventures of the residents living in Nova Scotia’s Sunnyvale Trailer Park, the streaming TV cult hit Trailer Park Boys comes to Parker Playhouse on Saturday, October 29 at 7:30 p.m. Friends and frequent felons Ricky, Julian and Bubbles share their ridiculous schemes, screw ups and running jokes — from their foul-mouthed, stoned and often drunk perspectives — in a hilarious live show intended for mature audiences. The “Still Drunk, High and Unemployed Tour,” finds the Trailer Park Boys having answered to the law in the “Community Service Variety Show” preaching the dangers of substance abuse to avoid jail time. The crew is now on the road without parole officers and Bubbles tries to create a new career for himself in the movie industry, Julian puts his latest money-making scams into action and Ricky has an idea that can “change the world!” Trailer Park Boys are Canada's most beloved miscreants from a small town in Nova Scotia, Canada. Robb Wells (Ricky), John Paul Tremblay (Julian) and Bubbles (Mike Smith) have created loyal and loveable characters on their television series and their message has spread globally. Trailer Park Boys began as a short film starring Tremblay and Wells, which debuted to rave reviews at the 1999 Atlantic Film Festival. -

Sounds Gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH KEN BURNS AND HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. SUBJECT: RACE IN AMERICA MODERATOR: THOMAS BURR, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: THE PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2016 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THOMAS BURR: (Sounds gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Thomas Burr. I'm the Washington correspondent for the Salt Lake Tribune, and the 109th President of the National Press Club. Our guests today are documentarian Ken Burns and Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. I would like to welcome our C-SPAN and Public Radio audiences. And I want to remind you, you can follow the action on Twitter using the hashtag NPClive. That's NPClive. Now it’s time to introduce our head table guests. I'd ask that each of you stand briefly as your name is announced. Please hold your applause until I have finished introducing the entire table. From your right, Michael Fletcher, senior writer for ESPN’s “The Undefeated,” and the moderator of today’s luncheon. Bruce Johnson, anchor at WUSA, Channel 9; Jeff Ballou, Vice President of the National Press Club and news editor at Al Jazeera English; Sharon Rockefeller, a guest of our speakers and President and CEO of WETA; Elisabeth Bumiller, Washington bureau chief of the New York Times. -

The Other America: White Working Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity and Immigration

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration July 2017 Harris Beider, Stacy Harwood, Kusminder Chahal Acknowledgments We thank all research participants for your enthusiastic participation in this project. We owe much gratitude to our two fabulous research assistants, Rachael Wilson and Erika McLitus from the University of Illinois, who helped us code all the transcripts, and to Efadul Huq, also from the University of Illinois, for the design and layout of the final report. Thank you to Open Society Foundations, US Programs for funding this study. About the Authors Harris Beider is Professor in Community Cohesion at Coventry University and a Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Stacy Anne Harwood is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Kusminder Chahal is a Research Associate for the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. For more information Contact Dr. Harris Beider Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations Coventry University, Priory Street Coventry, UK, CV1 5FB email: [email protected] Dr. Stacy Anne Harwood Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 111 Temple Buell Hall, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive Champaign, IL, USA, 61820 email: [email protected] How to Cite this Report Beider, H., Harwood, S., & Chahal, K. (2017). “The Other America”: White working-class views on belonging, change, identity, and immigration. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University, UK. ISBN: 978-1-84600-078-2 Photography credits: except when noted all photographs were taken by the authors of this report. -

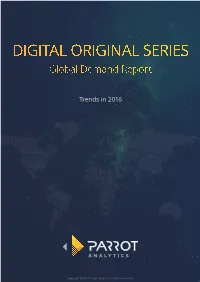

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report Trends in 2016 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Trends in 2016 Executive Summary } This year saw the release of several new, popular digital } The release of popular titles such as The Grand Tour originals. Three first-season titles — Stranger Things, and The Man in the High Castle caused demand Marvel’s Luke Cage, and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the for Amazon Video to grow by over six times in some Life — had the highest peak demand in 2016 in seven markets, such as the UK, Sweden, and Japan, in Q4 of out of the ten markets. All three ranked within the 2016, illustrating the importance of hit titles for SVOD top ten titles by peak demand in nine out of the ten platforms. markets. } Drama series had the most total demand over the } As a percentage of all demand for digital original series year in these markets, indicating both the number and this year, Netflix had the highest share in Brazil and popularity of titles in this genre. third-highest share in Mexico, suggesting that the other platforms have yet to appeal to Latin American } However, some markets had preferences for other markets. genres. Science fiction was especially popular in Brazil, while France, Mexico, and Sweden had strong } Non-Netflix platforms had the highest share in Japan, demand for comedy-dramas. where Hulu and Amazon Video (as well as Netflix) have been available since 2015. Digital Original Series with Highest Peak Demand in 2016 Orange Is Marvels Stranger Things Gilmore Girls Club De Cuervos The New Black Luke Cage United Kingdom France United States Germany Mexico Brazil Sweden Russia Australia Japan 2 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics.