MOBILE HOME on the RANGE: MANUFACTURING RUIN and RESPECT in an AMERICAN ZONE of ABANDONMENT by ALLISON BETH FORMANACK B.A., Univ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

A Review of Oregon's Manufactured Housing Policies

A REVIEW OF OREGON’S MANUFACTURED HOUSING POLICIES Katie Bewley Oregon State University AEC 406, Fall 2018 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................1 Project Statement and Approach ...............................................................................................................................2 Background .................................................................................................................................................................3 Community Attitudes Toward Manufactured Home Parks ....................................................................................3 Demographics of Manufactured Housing Use .......................................................................................................5 History of Manufactured Housing Policy ................................................................................................................6 Manufactured Housing and Policy in Oregon ............................................................................................................8 Case Study: Bend, Oregon ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Bend’s Manufactured Housing Policies ............................................................................................................... 11 Outcomes and Projections -

Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 66–75 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2391 Article “Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks Margarethe Kusenbach Department of Sociology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 1 August 2019 | Accepted: 4 October 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract In the United States, residents of mobile homes and mobile home communities are faced with cultural stigmatization regarding their places of living. While common, the “trailer trash” stigma, an example of both housing and neighbor- hood/territorial stigma, has been understudied in contemporary research. Through a range of discursive strategies, many subgroups within this larger population manage to successfully distance themselves from the stigma and thereby render it inconsequential (Kusenbach, 2009). But what about those residents—typically white, poor, and occasionally lacking in stability—who do not have the necessary resources to accomplish this? This article examines three typical responses by low-income mobile home residents—here called resisting, downplaying, and perpetuating—leading to different outcomes regarding residents’ sense of community belonging. The article is based on the analysis of over 150 qualitative interviews with mobile home park residents conducted in West Central Florida between 2005 and 2010. Keywords belonging; Florida; housing; identity; mobile homes; stigmatization; territorial stigma Issue This article is part of the issue “New Research on Housing and Territorial Stigma” edited by Margarethe Kusenbach (University of South Florida, USA) and Peer Smets (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands). © 2020 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

Racism and Discrimination As Risk Factors for Toxic Stress

Racism and Discrimination as Risk Factors for Toxic Stress April 28, 2021 ACEs Aware Mission To change and save lives by helping providers understand the importance of screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences and training providers to respond with trauma-informed care to mitigate the health impacts of toxic stress. 2 Agenda 1. Discuss social and environmental factors that lead to health disparities, as well as the impacts of racism and discrimination on public health across communities 2. Broadly discuss the role of racism and discrimination as risk factors for toxic stress and ACE Associated Health Conditions 3. Make the case to providers that implementing Trauma-Informed Care principles and ACE screening can help them promote health equity as part of supporting the health and wellbeing of their patients 3 Presenters Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH Chief Health Equity Officer, SVP, American Medical Association Ray Bignall, MD, FAAP, FASN Director, Kidney Health Advocacy & Community Engagement, Nationwide Children’s Hospital; Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine Roy Wade, MD, PhD, MPH Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania, Division of General Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia 4 Operationalizing Racial Justice Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH Chief Health Equity Officer, SVP American Medical Association Land and Labor Acknowledgement We acknowledge that we are all living off the stolen ancestral lands of Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. We acknowledge the extraction of brilliance, energy and life for labor forced upon people of African descent for more than 400 years. We celebrate the resilience and strength that all Indigenous people and descendants of Africa have shown in this country and worldwide. -

Fresno-Commission-Fo

“If you are working on a problem you can solve in your lifetime, you’re thinking too small.” Wes Jackson I have been blessed to spend time with some of our nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders— truly extraordinary people. When I listen to them tell their stories about how hard they fought to combat the issues of their day, how long it took them, and the fact that they never stopped fighting, it grounds me. Those extraordinary people worked at what they knew they would never finish in their lifetimes. I have come to understand that the historical arc of this country always bends toward progress. It doesn’t come without a fight, and it doesn’t come in a single lifetime. It is the job of each generation of leaders to run the race with truth, honor, and integrity, then hand the baton to the next generation to continue the fight. That is what our foremothers and forefathers did. It is what we must do, for we are at that moment in history yet again. We have been passed the baton, and our job is to stretch this work as far as we can and run as hard as we can, to then hand it off to the next generation because we can see their outstretched hands. This project has been deeply emotional for me. It brought me back to my youthful days in Los Angeles when I would be constantly harassed, handcuffed, searched at gunpoint - all illegal, but I don’t know that then. I can still feel the terror I felt every time I saw a police cruiser. -

Trailer Park Residents: Are They Worthy of Society's Respect Steve Anderson

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2017 Trailer Park Residents: Are They Worthy Of Society's Respect Steve Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Anderson, Steve, "Trailer Park Residents: Are They orW thy Of Society's Respect" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2095. https://commons.und.edu/theses/2095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRAILER PARK RESIDENTS: ARE THEY WORTHY OF SOCIETY’S RESPECT? By Steven Thomas Anderson Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 2015 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts May 2017 i Copyright 2017 Steven Thomas Anderson ii This thesis, submitted by Steven Thomas Anderson, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom this work has been done and is hereby approved. Clifford Staples Krista Lynn Minnotte Elizabeth Legerski This thesis is being submitted by the appointed advisory committee as having met all of the requirement of the School of Graduate Studies at the University of North Dakota and is hereby approved. Grant McGimpsey Dean of the School of Graduate Studies Date iii PERMISSION Title Trailer Park Residents: Are They Worthy of Society’s Respect? Department Sociology Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this university shall make it freely available for inspection. -

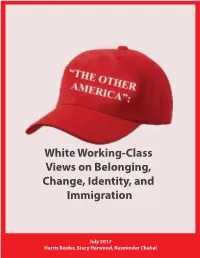

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration

White Working-Class Views on Belonging, Change, Identity, and Immigration July 2017 Harris Beider, Stacy Harwood, Kusminder Chahal Acknowledgments We thank all research participants for your enthusiastic participation in this project. We owe much gratitude to our two fabulous research assistants, Rachael Wilson and Erika McLitus from the University of Illinois, who helped us code all the transcripts, and to Efadul Huq, also from the University of Illinois, for the design and layout of the final report. Thank you to Open Society Foundations, US Programs for funding this study. About the Authors Harris Beider is Professor in Community Cohesion at Coventry University and a Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Stacy Anne Harwood is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban & Regional Planning at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Kusminder Chahal is a Research Associate for the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University. For more information Contact Dr. Harris Beider Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations Coventry University, Priory Street Coventry, UK, CV1 5FB email: [email protected] Dr. Stacy Anne Harwood Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 111 Temple Buell Hall, 611 E. Lorado Taft Drive Champaign, IL, USA, 61820 email: [email protected] How to Cite this Report Beider, H., Harwood, S., & Chahal, K. (2017). “The Other America”: White working-class views on belonging, change, identity, and immigration. Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University, UK. ISBN: 978-1-84600-077-5 Photography credits: except when noted all photographs were taken by the authors of this report. -

Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 10 December 2007 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation López, A. (2017). Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/ 10.31390/taboo.11.1.10 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterAntonio López 2007 73 Borat in an Age of Postironic Deconstruction Antonio López The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them. ... To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies—all this is indispensably necessary. Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth. —George Orwell, 19841 I will speak to you in plain, simple English. And that brings us to tonight’s word: ‘truthiness.’ Now I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s are gonna say, ‘hey, that’s not really a word.’ Well, anyone who knows me knows I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. -

Dignity Takings and Dehumanization: a Social Neuroscience Perspective

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 92 Issue 3 Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration Article 4 3-6-2018 Dignity Takings and Dehumanization: A Social Neuroscience Perspective Lasana T. Harris University College London Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lasana T. Harris, Dignity Takings and Dehumanization: A Social Neuroscience Perspective, 92 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 725 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol92/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIGNITY TAKINGS AND DEHUMANIZATION: A SOCIAL NEUROSCIENCE PERSPECTIVE LASANA T. HARRIS* I. INTRODUCTION Legal systems blend social cognition—inferences about the minds of others—with the social context.1 This is accomplished primarily through defining group boundaries. Specifically, legal systems dictate which people are governed within their jurisdiction. These people can all be considered part of the ingroup that the legal system represents. In fact, legal systems were created to facilitate people living together in large groups.2 This social contract requires people to be subject to the laws of their respective local, state, national, and international groups. Therefore, despite Rousseau’s theorizing of legal systems being created for all humanity, people governed by legal systems are assumed to belong to the relevant ingroup, however such a group is defined. -

Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990S Literary and Pop Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2018 Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture Eli W. Bromberg University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bromberg, Eli W., "Sex and Difference in the Jewish American Family: Incest Narratives in 1990s Literary and Pop Culture" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1156. https://doi.org/10.7275/11176350.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1156 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by ELI WOLF BROMBERG Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2018 Department of English Concentration: American Studies © Copyright by Eli Bromberg 2018 All Rights Reserved SEX AND DIFFERENCE IN THE JEWISH AMERICAN FAMILY: INCEST NARRATIVES IN 1990S LITERARY AND POP CULTURE A Dissertation Presented By ELI W. BROMBERG -

Sounds Gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH KEN BURNS AND HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. SUBJECT: RACE IN AMERICA MODERATOR: THOMAS BURR, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: THE PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MARCH 14, 2016 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THOMAS BURR: (Sounds gavel.) Welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Thomas Burr. I'm the Washington correspondent for the Salt Lake Tribune, and the 109th President of the National Press Club. Our guests today are documentarian Ken Burns and Harvard Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. I would like to welcome our C-SPAN and Public Radio audiences. And I want to remind you, you can follow the action on Twitter using the hashtag NPClive. That's NPClive. Now it’s time to introduce our head table guests. I'd ask that each of you stand briefly as your name is announced. Please hold your applause until I have finished introducing the entire table. From your right, Michael Fletcher, senior writer for ESPN’s “The Undefeated,” and the moderator of today’s luncheon. Bruce Johnson, anchor at WUSA, Channel 9; Jeff Ballou, Vice President of the National Press Club and news editor at Al Jazeera English; Sharon Rockefeller, a guest of our speakers and President and CEO of WETA; Elisabeth Bumiller, Washington bureau chief of the New York Times. -

Private Equity Giants Converge on Manufactured Homes

PRIVATE EQUITY GIANTS CONVERGE ON MANUFACTURED MASSIVE INVESTORS PILE INTO US MANUFACTURED HOME COMMUNITIES Within the last few years, some of the largest private equity firms, HOMES real estate investment firms, and institutional investors in the How private equity is manufacturing world have made investments in manufactured home communi - ties in the United States, a highly fragmented industry that has homelessness & communities are fighting back been one of the last sectors of housing in the United States that has remained affordable for residents. February 2019 In 2016, the $360 billion sovereign wealth fund for the Govern - ment of Singapore (GIC) and the $56 billion Pennsylvania Public KEY POINTS School Employees Retirement System, a pension fund for teachers and other school employees in the Pennsylvania, bought a I Within the last few years, some of the largest private equity majority stake in Yes! Communities, one of the largest owners of firms, real estate investment firms, and institutional investors manufactured home communities in the US with 44,600 home in the world have made investments in manufactured home sites. Yes! Communities has since grown to 54,000 home sites by communities in the US. buying up additional manufactured home communities. 1 I Manufactured home communities provide affordable homes for In 2017, private equity firm Apollo Global management, with $270 millions of residents and are one of the last sectors of affordable billion in overall assets, bought Inspire Communities, a manufac - housing in the United States. Across the country, they are home tured home community operator with 13,000 home sites. 2 to seniors on fixed incomes, low-income families, immigrants, Continued on page 3 people with disabilities, veterans, and others in need of low-cost housing.