Man and Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stamps of the Duchy of Modena

Philatelic Весом» Handbooks. No. 2. The Stamps of the Duchy of Modena AND THE Modenese Provinces. BY DR. EMILIO DIENA. P r ice f iv e Sh illin g s. Q ibfaňbtm £mået>wvst. PHILATELIC SECTION Philatelic Record Handbooks. No. 2. The Stamps of the Duchy of Modena AND THE Modenese Provinces. BY DR. EMILIO DIENA. P rice F iv e Sh illin g s. The Stamps OF THE Duchy of Modena AND THE MODENESE PROVINCES WITH THE Foreign Newspaper Tax Stamps of the Duchy BY Dr. EMILIO DIENA ~~r WITH SEVEN PLATES OF ILLUSTRATIONS emberit : PRINTED BY TRUSLOVE AND BRAY, LIMITED, WEST NORWOOD, S.E, L ů o ' N publishing an English version of the well- I known treatise on the Stamps of Modena by Dr. Emilio Diena, the proprietors of the Philatelic Record desire to express their sincere thanks to the author for his careful revision of the transla tion, as well as for sundry additions which do not appear in the original text. It is believed that the work now contains all information upon the subject available up to the present time. Manchester, November, 1905. PREFACE. OR some years I have wished to publish a treatise dealing specially with the stamps of Modena, based not onfy on the F decrees and postal regulations, but also upon an examination of the official documents and the registers of the Administration. At first the scarcity of information and afterwards the want of time to examine and arrange the material collected have prevented me from carrying out this scheme until the present time. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Y, Mat ?, ^-Triple Sheet

New YORK HERALD, SATURDAY, MAT ?, ^-TRIPLE SHEET. 3 - - .. i i more lethargy. But new that Ptodwont hu into Um dominions of whilst ihe Mne force end value m If H were In In the wWe* shall ala*-' hi considered it ebtifcbM, fcfc,vl« and (Siritibl* fr.t Ivnn, atton meat, Viatra, hoi not ..r immr Merely InioMM the fol'twtog urtldo, (be wh'iie in wiib ibo law* of tlu proved, by tbe regular and wtae eierdae of fraadmn, that Um of Um Awnnid present artlolo. riin'omtty ration m of and tor lieeoo u, uoa powtr retiming oomplinent. MU»Mth or «mh, 1M0, mi * »P»W1 h hfr owty of substitution all the other cutties of th .<iriur.it' to wlue.li are a* well a» it* Italian wormy sign »" ink Article »a. The prortaees ud Fnieigny, M,| "to moons ol this ibey Hu'Je-ded, » n>' atlad or io« ca of ovt u » Northern Italy, including Kitiguom nf dardlau »nc ;wr, of Bavoy to of P»r« abah be tntlnUiuid and regirdei m ab lM> military regwUtiMil aod the nup-mo chvge in..', i< viut. K.rope A iut> uut«j uf hi aOMMon the llaine o:' ell the territory tr^ northward of Ugine. said tieuty lie -de »tne wdb ibo bravest nut one of tin W..gt,»he h .* he Austrian 1 Itie Imnbirdo Vonitiu never laea.'rec.iin, to Uto of e on the two courts. referred to lire govern noma relative to '.be object* Of by provinces."alio 10 m more r , ut u is caone. -

Three Essays in Italian Economic History

Sapienza University of Rome Doctoral Thesis Three essays in italian economic history This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the european Phd program in Socio-economic and statistical studies Candidate Advisor Vitantonio Mariella Prof. Mauro Rota iii Declaration of Authorship I declare that this thesis titled Three essays in italian economic history and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that except where specific reference is made to the work of others, the contents of this dissertation are original and have not been submitted in whole or in part for consideration for any other degree or qualification in this, or any other university. This dissertation contains nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration with others, except as specified in the text and Acknowledgements. To my father v Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Mauro Rota for his precious guidance, mentorship and support, without whom the research would not have been possible. A special thank goes to Prof. David Chilosi, whose help made my Visiting experience particularly fruitful. I would also like to thank Francesco S.L, Francesco B., Paolo, Teresa, Lucrezia, Serena, Luigi and my cousins Peppone and Peppino. Without them my life would have been much sadder. My biggest thanks goes to my family for all the support shown me through this research experience. My most sincere gratitude goes to Costanza for her patience, support and love, who makes my life a wonderful adventure. And sorry for being even grumpier than normal whilst I wrote this thesis! All of you stimulated my mind to move beyond its limits. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

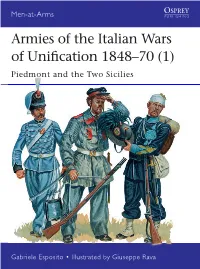

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

Postal Communications from the United Kingdom to Italy 1840 -1874

Postal Communications from the United Kingdom to Italy 1840 -1874 This exhibit addresses the postal communications between the United Kingdom and Italy, focusing on the complex historical period from 1840 to 1874. These dates saw the introduction Section 1 - Old States Frame of the first postage stamp (1840), the explosion of the industrial revolution in Britain, and the struggle of the Italian states to gain national unity after the Congress of Vienna. During this Chapter 1 - Kingdom of the Two Sicilies 1 time, new and much faster ways of communication (mostly the train and the steamship) co- Chapter 2 - Grand Duchy of Tuscany 1 existed with the remnants of old agreements, or in some cases the lack thereof, which allowed for the mail to be carried at different rates and through different routes and different countries. Chapter 3 - States of the Church & Rome 1 The result is a complex, fascinating array of rates and routes that this exhibit aims to describe. Chapter 4 - Duchies of Parma, Modena and Lucca 2 Chapter 5 - Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia 2 Chapter 6 - Kingdom of Sardinia 2 Section 2 – Kingdom of Italy Chapter 7 - New Nation: Countrywide Rates 3 Chapter 8 - New Challenges: Cholera 3 Chapter 9 - New Challenges: The Impact of War 3 The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) reshaped Europe Essential Bibliography 1. Jane and Michael Moubray: British Letter Mail to Overseas Destination 1840-1875. RPSL, London 2018 2. Lewis Geoffrey: The 1836 Anglo-French Postal Convention, The Royal Philatelic Society London, 2015. The first section covers rates and routes separately for each of the following major Old 3. -

Lucca & Tuscany

Lucca & Tuscany Lucca – October 1-2-3-4th 2020 2 Lucca: city of culture, arts and crafts We will celebrate our annual Big Party by paying tribute to two geniuses: Leonardo da Vinci and Giacomo Puccini ear Confrères and Con- With a city of such glorious his- Leonardo himself in a famous let- D soeurs, dear Friends, we are tory, we can only admire and pay ter of 1482, in which he states: “I infinitely grateful to the Friends tribute to the character and sen- have no rival in building bridges, of Lucca who give us the great sitivity of its inhabitants, tangible fortifications and catapults, and joy of being together again in an even through the impeccable or- also other secret tools that I don’t extraordinary place. A wonderful ganization of our meeting by the dare to describe on this page. My city, with a millenary histor: origi- members of the Bailliage of Lucca painting and my sculpture com- nally born as a Ligurian settlement, and by our confidential agency, pare with those of any other art- then Etruscan in the 5th century Clementson T.O. represented by ist. I excel in formulating riddles B.C, later a Roman city, then a Enrico and Monica Spalazzi to- and inventing knots. And I make Longobard Duchy, then passed gether with their staff. Not to for- cakes that have no equal”. under the Franks; constituted as a get the creativity and originality Leonardo’s exceptional inventions free Municipality since 1119, it re- of the exceptional centuries-old for cooking are known. -

1 the Founding of Arcetri Observatory in Florence

THE FOUNDING OF ARCETRI OBSERVATORY IN FLORENCE Simone Bianchi INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi, 5, 50125, Florence, Italy [email protected] Abstract: The first idea of establishing a public astronomical observatory in Florence, Capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, dates to the mid of the 18th century. Initially, the use of a low building on a high ground was proposed, and the hill of Arcetri suggested as a proper location. At the end of the century, the Florence Observatory - or Specola - was built instead on a tower at the same level as the city’s centre. As soon as astronomers started to use this observatory, they recognized all its flaws and struggled to search for a better location. Giovanni Battista Donati, director of the Specola of Florence from the eve of the Italian Unification in 1859, finally succeeded in creating a new observatory: first, he obtained funds from the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy to build an equatorial mount for the Amici 28-cm refractor, which could not be installed conveniently in the tower of the Specola; then, he went through the process of selecting a proper site, seeking funds and finally building Arcetri Observatory. Although Donati was a pioneer of spectroscopy and astrophysics, his intent was to establish a modern observatory for classical astronomy, as the Italian peninsula did not have a national observatory like those located in many foreign capitals – Florence was the capital of the Kingdom of Italy from 1865 to 1871. To promote the project, Donati made use of writings by one of the most authoritative European astronomers, Otto Wilhelm Struve. -

The Etruscans14-1-2020

The Etruscans Erodoto in the well-known Tales describes that in the XIII B.C. Atys, son of Manes, because of a serious famine in Lidia, in the Minor Asia, divided the population in two groups entrusting one with Tirreno in order that he could take them to a new fruitful land. Once they arrived in the north of Tiber these people took the name of Tirreni ( as per the name of the Prince that had took them there ). Besides Elianico, a Greek historian of Mitilene was convinced that the Lidi together with the nomad people of Pelasgi, were the settlers of the Etruria. Dionigi from Alicarnasso a Greek historian arrived in Rome was not in agreement with this opinion differently from Virgilio, as according to him the inhabitants of the Tuscia were a population of native origin said of the Rasenna. According to recent studies we know that in Etruria there were people coming from the Middle East as well as from the central Europe, dating from IX century B.C. with the development of what has been called the civilization Villanoviana. The land, that was settled between the VII and the VI century B.C., was the corner included between the two most important rivers of Central Italy, Arno and Tevere which was limited in the North by Liguri, and in the East by Umbri and Sabini and in the South by Latini. During this time called “Oriental time”, the exchange between Orient and Greece became rather substantial as besides of the goods there were also the handicrafts men coming with the new techniques like the lathe for the working of metals. -

The Etruscans Erodoto in the Well-Known Tales Describes That In

The Etruscans Erodoto in the well-known Tales describes that in the XIII B.C. Atys, son of Manes, because of a serious famine in Lidia, in the Minor Asia, divided the population in two groups entrusting one with Tirreno in order that he could take them to a new fruitful land. Once they arrived in the north of Tiber these people took the name of Tirreni ( as per the name of the Prince that had took them there ). Besides Elianico, a Greek historian of Mitilene was convinced that the Lidi together with the nomad people of Pelasgi, were the settlers of the Etruria. Dionigi from Alicarnasso a Greek historian arrived in Rome was not in agreement with this opinion differently from Virgilio, as according to him the inhabitants of the Tuscia were a population of native origin said of the Rasenna. According to recent studies we know that in Etruria there were people coming from the Middle East as well as from the central Europe, dating from IX century B.C. with the development of what has been called the civilization Villanoviana. The land, that was settled between the VII and the VI century B.C., was the corner included between the two most important rivers of Central Italy, Arno and Tevere which was limited in the North by Liguri, and in the East by Umbri and Sabini and in the South by Latini. During this time called “Oriental time”, the exchange between Orient and Greece became rather substantial as besides of the goods there were also the handicrafts men coming with the new techniques like the lathe for the working of metals. -

Coins of the Italian States) © Stephen Kuhl, March 2019

Monete Degli Stati Italiani (Coins of the Italian States) © Stephen Kuhl, March 2019 Ciao amici! Attendees of the February 2019 meeting of the Stephen James Central Savannah River Area Coin Club (SJCSRACC) were treated to an extra special educational program by member Walter Kubilius. Walt is renowned for his in-depth research and excellently built presentations, and his program Coins of the Italian States, 1760-1870 was no exception – it was interesting and professionally done! His program really piqued my interest in this period of Italian Kingdoms: history, so like any good numismatist I began researching to learn more. This article, which in general addresses the Lombardy-Venetia minor (copper and silver) coinage of the period, is a result of Sardinia The Papal States the research that followed and includes photos of some of The Two Sicilies the coinage Walt presented. If you find this subject interesting, there are many excellent sources of information Dukedoms: available on the internet, many more than the references listed at the end of this article. Grand Duchy of Tuscany Buona lettura! Duchy of Parma th Duchy of Modena and This article covers the evolution of coinage as the early 19 century Italian states are first Reggio conquered by the French and, after regaining independence, they transition from small Duchy of Lucca independent states to a unified country in the second half of the century. As can be expected, along the way there was significant political intrigue and many subjugations which changed the coins of the period. With respect to the political geography of the Italian Peninsula, it was comprised of four Kingdoms and four main Dukedoms (see sidebar and map) although this tended to flux as the imperial European powers waged their endless wars.