Cecilia Fe L Sta Maria1 Monumentalizing the Urban and Concealing the Rural/Coastal a Spatial Reading of Matnog, Sorsogon, Philip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

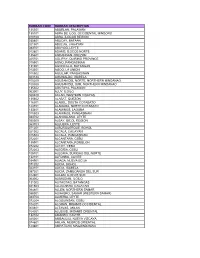

Municipality Name of Operator Name of Outlet Address 1 Bacon Jovic Sarmiento IBSP Market Site, Bacon Dist., Sorsogon City 2 Baco

NATIONAL FOOD AUTHORITY Province of Sorsogon Cabid-an, Sorsogon City MASTERLIST OF ACCREDITED RETAILERS As of January, 2017 Municipality Name of Operator Name of Outlet Address 1 Bacon Jovic Sarmiento IBSP Market Site, Bacon Dist., Sorsogon City 2 Bacon Narciso Ariate IBSP Public Market, Bacon Dist., Sorsogon City 3 Bacon Simeon Guemo IBSP Market Site, Bacon Dist., Sorsogon City 4 Barcelona Pinkee P. Galias IBSP Market Site, Barcelona, Sorsogon 5 Barcelona Romelito Diaz IBSP Poblacion,Barcelona, Sorsogon 6 Barcelona Violeta Galias IBSP Public Market, Barcelona, Sorsogon 7 Bulusan Maria Agnes D. Fulo IBSP Public Market, Bulusan, Sorsogon 8 Bulusan Antonio F. Frando IBSP Public Market, Bulusan, Sorsogon 9 Bulan Amalia Jaofrancia IBSP Zone 6, Bulan, Sorsogon 10 Bulan BUFAFIDECO IBSP Public Market, Bulan, Sorsogon 11 Bulan Januaria Hilario IBSP Public Market, Bulan, Sorsogon 12 Bulan Merly dela Paz IBSP San Francisco, Bulan, Sorsogon 13 Bulan Vicky Tee IBSP Public Market, Bulan, Sorsogon 14 Casiguran Aurora Garcia IBSP Public Market, Casiguran, Sorsogon 15 Castilla Cris Mendoza IBSP Pob,Satellite Market, Castilla, Sorsogon 16 Castilla Jocelyn Agarap IBSP Cumadcad, Castilla, Sorsogon 17 Donsol Marites Abitria IBSP Public Market, Donsol, Sorsogon 18 Donsol Berzelisa Diaz IBSP Public Market, Donsol, Sorsogon 19 Gubat Jaime Pura IBSP Public Market, Gubat, Sorsogon 20 Gubat Leo Lelis IBSP Public Market, Gubat, Sorsogon 21 Gubat Estela Enguerra IBSP Public Market, Gubat, Sorsogon 22 Gubat Consolacion E. Estipona IBSP Public Market, Gubat, Sorsogon -

Uimersity Mcrofihns International

Uimersity Mcrofihns International 1.0 |:B litt 131 2.2 l.l A 1.25 1.4 1.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIAL 1010a (ANSI and ISO TEST CHART No. 2) University Microfilms Inc. 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right In equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page Is also filmed as one exposure and Is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or In black and white paper format. * 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarify on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available In black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. -

Entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility at 4:00PM on November 30, 2019

Situation Report No. 1 02 December 2019 TYPHOON TISOY Introduction Typhoon Tisoy (Kammuri) entered the Philippine area of responsibility at 4:00PM on November 30, 2019. Based on the December 2, 2019 4 pm weather advisory issued by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAG-ASA), the eye of Typhoon "TISOY" was located at 155 km East of Juban, Sorsogon. Moving at 15 kilometers per hour, it is expected to make landfall in Sorsogon, Albay, Catanduanes, and Camarines Sur between 5 pm to 8 pm tonight (December 2). Storm Warning number 3 has been issued for the whole of Bicol Region, Romblon and portions of Quezon Province. Similarly, storm surge warnings have been issued to the coastal areas of Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes, Quezon and Samar, with surge possibly reaching up to 3 meters high. Typhoon Track from PAG-ASA A view from the rooftop of Educo Central office in as Typhoon Tisoy (Kammuri) approaches the region. Government response: Since December 1, local government units in the Bicol region has initiated preemptive evacuation on identified low lying and flood prone areas. The Department of Education has ordered the supesnsion of classes in both private and As of 12 noon of today, Educo and DSWD Region 5 has initially recorded 7,450 displaced families (29,493 individuals) due to the pre-emptive evacuation. 1 Situation Report No. 1 02 December 2019 Displaced Persons Inside Evacuation Outside Evacuation Centers Centers Families Individuals Families Individuals 7226 28680 224 963 Camarines Norte Vinzons 896 3181 Basud 47 152 Mercedes 57 241 Total 1000 3574 Camarines Sur Del Gallego 50 255 Minalabac 5 27 Calbanga 379 1168 Magaraw 24 113 Caramoan 509 2222 Saganay 11 55 Tinambac 402 1917 Baao 93 462 Buhi 184 775 Total 1564 6532 93 462 Catanduanes Baras 242 1190 San Miguel 15 70 Pandan 3 11 San Anders 40 141 Virac 668 3245 Caramoran 582 2899 1510 7415 40 141 Albay Guinubatan 1211 4619 91 360 Oas 50 225 Total 1261 4844 91 360 2 Situation Report No. -

A Political Economy Analysis of the Bicol Region

fi ABC+: Advancing Basic Education in the Philippines A POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS OF THE BICOL REGION Final Report Ateneo Social Science Research Center September 30, 2020 ABC+ Advancing Basic Education in the Philippines A Political Economy Analysis of the Bicol Region Ateneo Social Science Research Center Final Report | September 30, 2020 Published by: Ateneo de Naga University - Ateneo Social Science Research Center Author/ Project lead: Marlyn Lee-Tejada Co-author: Frances Michelle C. Nubla Research Associate: Mary Grace Joyce Alis-Besenio Research Assistants: Jesabe S.J. Agor and Jenly P. Balaquiao The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government, the Department of Education, the RTI International, and The Asia Foundation. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 6 Sampling Design .............................................................................................................. 6 Data Collection -

31 October 2020

31 October 2020 At 5:00 AM, TY "ROLLY" maintains its strength as it moves closer towards Bicol Region. The eye of Typhoon "ROLLY" was located based on all available data at 655 km East Northeast of Virac, Catanduanes. TCWS No. 2 was raised over Catanduanes, the eastern portion of Camarines Sur, Albay, and Sorsogon. While TCWS No.1 was raised over Camarines Norte, the rest of Camarines Sur, Masbate including Ticao and Burias Islands, Quezon including Polillo Islands, Rizal, Laguna, Cavite, Batangas, Marinduque, Romblon, Occidental Mindoro including Lubang Island, Oriental Mindoro, Metro Manila, Bulacan, Pampanga, Bataan, Zambales, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, Pangasinan, Benguet, Ifugao, Nueva Vizcaya, Quirino, and the southern portion of Isabela, Northern Samar, the northern portion of Samar, the northern portion of Eastern Samar, and the northern portion of Biliran. At 7:00 PM, the eye of TY "ROLLY" was located based on all available data at 280 km East Northeast of Virac, Catanduanes. "ROLLY" maintains its strength as it threatens Bicol Region. The center of the eye of the typhoon is likely to make landfall over Catanduanes early morning of 01 November 2020, then it will pass over mainland Camarines Provinces tomorrow morning, and over mainland Quezon tomorrow afternoon. At 10:00 PM, the eye of TY "ROLLY" was located based on all available data including those from Virac and Daet Doppler Weather Radars at 185 km East of Virac, Catanduanes. Bicol Region is now under serious threat as TY "ROLLY" continues to move closer towards Catanduanes. Violent winds and intense to torrential rainfall associated with the inner rainband-eyewall region will be experienced over (1) Catanduanes tonight through morning; (2) Camarines Provinces and the northern portion of Albay including Rapu-Rapu Islands tomorrow early morning through afternoon. -

Agrarian Reform Communities Project II

Environment and Social Safeguards Monitoring Report 2009 - 2017 Project Number: 37749-013 Loan 2465/Loan 8238(OFID) May 2019 Philippines: Agrarian Reform Communities Project II Prepared by ARCP II – NPCO for the Asian Development Bank This report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and neither the ADB nor the Government shall be held liable for its contents. ABBREVIATIONS/GLOSSARY ARC Agrarian Reform Communities ARC Clusters Agrarian Reform Community Clusters ARCP II Second Agrarian Reform Communities Project CNC Certificate of Non-Coverage CNO Certificate of Non-Overlap CP Certification Precondition DAR Department of Agrarian Reform ECC Environmental Clearance Certificate EMB Environmental Management Bureau GOP Government of the Philippines IP Indigenous Peoples LGU Local Government Unit NCIP National Commission on Indigenous Peoples NSAC National Subproject Approval Committee (composed of representatives (Assistant Secretary/Director level) from Department of Agriculture(DA)/National Irrigation Administration(NIA); NCIP, Department of Environment & Natural Resources (DENR)/Environment & Management Bureau (EMB); Department of Public Works & Highways (DPWH); Dept of Budget & Management (DBM) , Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) ; Department of Finance (DOF)/Bureau of Local Government Funds(BLGF) and Municipal Development Funds Office (MDFO) and National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) NGALGU National Government Assistance to Local Government Unit PAPs Project Affected Persons RSAC Regional Subproject Approval Committee (composed of Regional representatives of the DAR, DA, DPWH, DENR, NCIP and NEDA) This environmental and social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

Citizen's Charter

PORT MANAGEMENT OFFICE BICOL CCIITTIIZZEENN’’SS CCHHAARRTTEERR PMO BICOL, April 2017 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I PPA - PMO BICOL CITIZEN’S CHAPTER 1 II Background Information about the Philippine Ports Authority (PPA) 2 Vision, Mission, Mandate, Corporate Values, Objectives and Functions 3-6 III PPA Pledge of Performance 7 IV PPA Wide Telephone Directory 8 V Scope /Coverage and Definition of Terms 9-10 VI General Information About the PMO Bicol Ports Port Profiles, Geographical Locations, Port Facilities (Vertical and Horizontal) 11-21 VII PMO Bicol Redress and Feedback Mechanism with Directory for Complaints 22-23 VIII List of Frontline Services of PMO Bicol Ports 24-25 IX Documentary Requirements and Step by Step Procedure to Obtain a Particular Service including OPR and Maximum Time to Conclude the Process 26-67 X Feedback Form (Pananaw o Puna) [in Filipino] Annex “A” Customer Feedback Form [in English] Annex “B” PMO Bicol Telephone Directory Annex “C” “Seguridad sa Puerto, i-Text mo” Annex “D” PMO BICOL, April 2017 Page 2 THE PHILIPPINE PORTS AUTHORITY ( PPA ) A. Background Information PPA was created through Presidential Decree (PD) No. 505, otherwise known as the “Philippine Port Authority Decree of 1974”, issued on July 11, 1974. Under the said PD, PPA is given general jurisdiction and control over all persons, groups and entities that are already existing or are still being proposed to be established within the different port districts throughout the country. PPA, in coordination with other government agencies, is also mandated to prepare and update annually a “Ten-Year Philippine Port Development Program” which shall embody the integrated plan for the development of the country’s ports and harbors. -

Summary of Barangays Susceptible to Bulusan

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE OF VOLCANOLOGY AND SEISMOLOGY SUMMARY OF BARANGAYS SUSCEPTIBLE TO BULUSAN LAHARS MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY HIGH MODERATE LOW SAFE RIVER CHANNEL BARCELONA Alegria N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Bagacay N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Bangate N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto BARCELONA Bugtong N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Cagang - - - YES BARCELONA Fabrica N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog, Tagdon BARCELONA Jibong N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Lago N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Layog N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA Luneta N N PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Macabari N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Bangati, Bon-ot BARCELONA Mapapac N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Olandia N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Paghaluban N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA Poblacion Central N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Poblacion Norte N PARTLY PARTLY - Barcelona BARCELONA Poblacion Sur - - - YES BARCELONA Putiao N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA San Antonio N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA San Isidro N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA San Ramon N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto, Layog BARCELONA San Vicente N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY BArcelona BARCELONA Santa Cruz N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto, Bon-ot, Layog BARCELONA Santa Lourdes N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona, Tagdon BARCELONA Tagdon N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BULAN A. Bonifacio - - - YES BULAN Abad Santos - - - YES BULAN Aguinaldo - - - YES BULAN Antipolo - - - YES BULAN Beguin - - - YES BULAN Benigno S. Aquino (Imelda) - - - YES BULAN Bical - - - YES BULAN Bonga - - - YES BULAN Butag - - - YES BULAN Cadandanan - - - YES BULAN Calomagon - - - YES BULAN Calpi - - - YES BULAN Cocok-Cabitan - - - YES BULAN Daganas - - - YES BULAN Danao - - - YES BULAN Dolos - - - YES BULAN E. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 9, Issue, 03, pp.48498-48505, March, 2017 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE ASSESSMENT OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM POTENTIALITIES OF SORSOGON PHILIPPINES *Vivien L. Chua, Ed. D. Sorsogon State College, Sorsogon City, 4700, Philippines ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: This paper assessed the local tourism potentialities of Sorsogon province in the Philippines. Data Received 14th December, 2016 gathering employed an online Delphi-based process to evaluate the criteria in measuring potentialities Received in revised form of local tourism; one hundred and fifty (150) respondents were selected via stratified random 02nd January, 2017 sampling; and data analysis used descriptive statistics and non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Accepted 17th February, 2017 Results suggest that to ensure sustainability to existing tourism potentialities, Sorsogon has to focus Published online 31st March, 2017 on the importance of quality tertiary education, the provision of stable local employment, the promotion of healthy and balanced community life, as well as prioritizing the basic social services of Key words: its communities. Sorsogon tourism destinations are characterized by the four (4) tourism typologies Local tourism, based on travel motivation: ecotourism, econautical, cultural, and educational tourism and findings Potentialities, indicate that most of Sorsogon’s tourist destinations remained untouched by commercialism however, Sustainable development, there is a need to balance the travel motivators and tourist personalities with the psychological needs Tourism psychology, of the local communities in order to sustainably manage these tourism destinations. This study Tourism typologies, recommends that aside from human resources, there’s a need for stronger local government support Sorsogon. -

North–South Railway Project South Line

North–South Railway Project South Line Project Brief for the Opportunity to Design, Build, Finance, Operate, and Maintain a Landmark Commuter and Long–Haul Rail Asset in the Republic of the Philippines THE NORTH–SOUTH RAILWAY PROJECT SOUTH LINE (“NSRP SOUTH LINE” OR THE “PROJECT”) IS A KEYSTONE PROJECT OF THE PHILIPPINES’ DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS (DOTC) AND PHILIPPINE NATIONAL RAILWAYS (PNR). THE PROJECT IS INTENDED TO SERVE AS THE SOLE RAIL BACKBONE CONNECTING METRO MANILA TO CURRENTLY UNDERSERVED AREAS IN SOUTHERN LUZON. A compelling opportunity exists for a consortium of leading rail system developers and operators to: . Provide a world-class passenger rail service, including infrastructure, signaling, and rolling stock, by developing 56km commuter rail and 653km long-haul passenger rail services . Capitalize on the Philippines’ economic and urban growth by providing critical connectivity infrastructure for the country. The Philippines has been investment grade for over 2 years, with Moody’s further raising the sovereign credit rating to Baa2 in December 2014 . Design, build, finance, operate, and maintain the largest public–private partnership (PPP) in the Philippines to date. Over the last five years, the Philippines has been one of the most successful PPP markets in Southeast Asia. THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES The Republic of the Philippines is an archipelago comprising more than 7,100 islands located in Southeastern Asia. It has a total area of 300,000 km2, with the two largest islands (Luzon and Mindanao) taking up over 66% of the land area. With over 100 million people, the archipelago is the seventh most populated Asian country and 12th most populated country in the world.