Place-Names and Language-Contact in the Beauly Area, Inverness-Shire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

Conservation of the Wildcat (Felis Silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the Conservation Status and Assessment of Conservation Activities

Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities Urs Breitenmoser, Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten February 2019 Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 2 Cover photo: Wildcat (Felis silvestris) male meets domestic cat female, © L. Geslin. In spring 2018, the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan Steering Group commissioned the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group to review the conservation status of the wildcat in Scotland and the implementation of conservation activities so far. The review was done based on the scientific literature and available reports. The designation of the geographical entities in this report, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The SWCAP Steering Group contact point is Martin Gaywood ([email protected]). Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 3 List of Content Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Summary 5 1. Introduction 7 2. History and present status of the wildcat in Scotland – an overview 2.1. History of the wildcat in Great Britain 8 2.2. Present status of the wildcat in Scotland 10 2.3. Threats 13 2.4. Legal status and listing 16 2.5. Characteristics of the Scottish Wildcat 17 2.6. Phylogenetic and taxonomic characteristics 20 3. Recent conservation initiatives and projects 3.1. Conservation planning and initial projects 24 3.2. Scottish Wildcat Action 28 3.3. -

Timetable from Monday 16Th August 2021

Timetable from Monday 16th August 2021 Days of Operation Monday to Friday Service Number 21 Service Description Dingwall - Cromarty Service No. 21 21 21 21B 21 21 21 21B 21 Sch MWF F MW F F NF Sch #Sch Sch Sch Dingwall Academy - - - Z1335 - - - Z1545 - Dingwall Tesco - 0845 1215 1337 1405 1435 1435 1547 1745 Dingwall Hill Street - 0850 1220 1339 1410 1440 1440 1549 1750 Maryburgh - - - 1342 - - - 1552 - Conon Bridge - - - 1345 - - - 1555 - Easter Kinkell - 0903 1233 1355 1423 1453 1453 1605 1803 Culbokie Shops - 0910 1240 1402 1430 1500 1500 1612 1810 Culbokie School Croft - 0913 1243 1405 1433 1503 1503 1615 1813 Resolis Primary School 0843 - 1250 - 1440 1510 1510 - - Balbalir Aird Place 0845 - 1252 - 1442 1512 - - - Newhall Ellenslea 0847 - 1254 - 1444 1514 - - - Jemimaville 0851 - 1258 - 1448 1518 - - - Cromarty 0859 - 1306 - 1456 1526 - - - Codes: MWF Mon Wed Fri only Sch Schooldays only F Fridays only #Sch School holidays only MW Monday & Wednesday Z1 Use Stance 2 at Dingwall Academy NF Not Fridays Days of Operation Monday to Friday Service Number 21 Service Description Dingwall - Cromarty Service No. 21B 21B 21 21 21 21B 21 21 21 21 Sch #Sch MWF MW F F Sch NF NF F #Sch Sch Sch Sch Sch Cromarty - - 0925 1310 1325 1325 1445 - 1456 - Jemimaville - - 0933 1318 1333 1333 1453 - 1504 1538 Newhall Ellenslea - - 0937 1322 C1337 1338 1456 - 1507 1541 Balblair Aird Place - - 0939 1324 1339 - 1459 - 1510 1543 Resolis Primary School - - 0941 1326 1341 - 1501 - 1512 1546 Springfield - - - - - 1348 - - - - Culbokie Easter Culbo Jct - - - - - -

“Hardwood Development for North Scotland

2017 ICF North Scotland Hardwood Development for North Scotland: Progress & Options Kiltarlity/ Beauly, Inverness-shire - 27th April 2017 Subject Matter This meeting will examine the progress in realising the potential of hardwood trees for timber and woodfuel production in the north of Scotland as well as at options and Research and Development needs for the future. There is a long-standing history of hardwood silviculture (oak, ash, elm, beech. sycamore) on certain private estates in the region. However recent decades have seen a growing perception that hardwoods cannot be grown economically at this latitude (57-59 degN) despite experience to the contrary from Scandinavia and development work by Highland Birchwoods etc. Few hardwood stands in the region have been managed for timber since the 1950’s. Recent increases in demand for estate woodfuel and interest in local/community woodland management have raised the profile of hardwoods. The Forestry Commission aims to manage a proportion of their hardwood resources for timber. We now need to consider what we already know and what more we need to know for the next steps. In the morning session, we have speaker presentations from relevant Forestry Commission and Forest Research staff, and from private consultants. After lunch, we will visit key local private woodlands where hardwoods are being tended for timber. Tea and Coffee will be provided. Attendees must bring their own packed lunch. Venue The morning indoor component of the meeting on Thursday 27th April will be held at Kiltarlity Village Hall near Beauly - 12 miles west of Inverness. Field visits in the afternoon will be to relevant woodland sites in the locality, under private ownership. -

A Message from Our Interim Moderator

www.kiltarlityandkirkhill.org.uk Kiltarlity and Wardlaw Churches A MESSAGE FROM OUR INTERIM MODERATOR Dear Friends, There is a moving story about a man called Charnet who was a political prisoner in France in the days of Napoleon. He was thrown into prison simply because he had accidentally, by a remark, offended the emperor Napoleon. Cast into a dungeon cell, presumably left to die, as the days and weeks and months passed by, Charnet became embittered at his fate. Slowly but surely he began to lose his faith in God. And one day, in a moment of rebellious anger, he scratched on the wall of his cell, "All things come by chance," which reflected the injustice that had come his way by chance. He sat in the darkness of that cell growing more bitter by the day. There was one spot in the cell where a single ray of sunlight came every day and remained for a little while. And one morning, to his absolute amazement, he noticed that in the hard, earthen floor of that cell a tiny, green blade was breaking through. It was something living, struggling up toward that shaft of sunlight. It was his only living companion, and his heart went out in joy toward it. He nurtured it with his tiny ration of water, cultivated it, and encouraged its growth. That green blade became his friend. It became his teacher in a sense, and finally it burst through until one day there bloomed from the little plant a beautiful, purple and white flower. Once again Charnet found himself thinking thoughts about God. -

C:\MYDOCU~1\ACCESS~2\Aird\New Aird Inside.Pmd

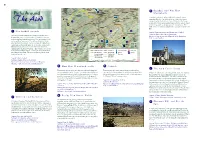

Wester To Inverness Lovat Kirkhill 6 Kirkhill and Wardlaw Wardlaw 6 Paths Around Beauly Mausoleum Ferry Brae Bogroy A roadside path to the village of Kirkhill and to the burial To Lentran Beauly ground used by the Clan Fraser of Lovat. Robert the Bruce’s The Aird 7 Inchmore chamberlain was Sir Alexander Fraser. His brother, Sir Simon A862 acquired the Bisset Lands around Beauly when he won the hand ! of its heiress, and these lands became the family home. The walk can be extended by following the cycle route as far as Ferry Brae. 1 Newtonhill circuits 1 2 ! Cabrich Approx 5 kms round trip to the Mausoleum (3.1 miles) Moniack Newtonhill Castle Parking at Bogroy Inn or at the Mausoleum This varied circular walk on quiet country roads provides a A833 A Bus service from Inverness and Dingwall to the Bogroy Inn flavour of what the Aird has to offer; agricultural landscape, 5 To Easy - sensible footwear natural woodland, plantations of Scots Pine and mature beech To Kiltarlity Kirkton and magnificent panoramas. The route provides links to the 4 3 Muir other paths in the network. It offers views to the Fannich and Belladrum Mám Mòr To the Affric ranges to the north and west, views to the east down the 8 Reelig Great Moray Firth and some of the best views to Ben Wyvis. The THE AIRD A Glen Glen Way climb from Reelig Glen is worth the effort with the descent via Newtonhill and Drumchardine, a former weaving community A Phoineas Newtonhill Circuit The Cabrich Tourist Information A Access point providing an easy finish. -

Driving Edinburgh to Gairloch a Personal View Ian and Lois Neal

Driving Edinburgh to Gairloch a personal view Ian and Lois Neal This is a personal account of driving the route from Edinburgh to Gairloch, supplemented by words and pictures trawled from the Internet. If we have used your material recklessly, we apologise; do let us know and we will acknowledge or remove it. Introduction to the Area As a settlement, Gairloch has a number of separately named and distinct points of focus. The most southerly is at Charlestown where you can find Gairloch's harbour. In more recent times the harbour was the base for the area's fishing fleet. Gairloch was particularly renowned for its cod. Much of the catch was dried at Badachro on the south shore of Loch Gairloch before being shipped to Spain. Today the harbour is used to land crabs, lobsters and prawns. Much of this also goes to the Spanish market, but now it goes by road. From here the road makes its way past Gairloch Golf Club. Nearby are two churches, the brown stone Free Church with its magnificent views over Loch Gairloch and the white-harled kirk on the inland side of the main road. Moving north along the A832 as it follows Loch Gairloch you come to the second point of focus, Auchtercairn, around the junction with the B8021. Half a mile round the northern side of Loch Gairloch brings you to Strath, which blends seamlessly with Smithtown. Here you will find the main commercial centre of Gairloch. Gairloch's history dates back at least as far as the Iron Age dun or fort on a headland near the golf club. -

Meeting with Police 4 November 2003

Scheme THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Community Services: Highland Area RAUC Local Co-ordination Meeting Job No. File No. No. of Pages 4 SUMMARY NOTES OF MEETING + Appendices Meeting held to Discuss: Various Date/Time of Meeting: 22nd April 2021 at 10.30 Issue Date* 26/04/2021 Author Kirsten Donald Draft No. 1 REF ACTIONS 1.0 Attending / Contact Details Highland Council Community Services; Area Roads Alistair MacLeod [email protected] Alison MacLeod [email protected] Jonathan Gunn [email protected] Adam Lapinski [email protected] Holly Fraser [email protected] Andrew MacIver [email protected] Lucy Tonkin [email protected] Kevin fulton [email protected] Openreach Duncan MacLennan [email protected] Bruce McClory [email protected] Scottish & Southern Energy Andrew Ewing [email protected] Gary Hay [email protected] Scottish Water Darren Pointer [email protected] Emma west [email protected] Bear Scotland Mike Gray [email protected] SGN Alex Torrance [email protected] Martin Gemmell [email protected] Network Rail David Murdoch [email protected] 2.0 Apologies / Others Courtney Mitchel [email protected] 3.0 Minutes of previous Highland RAUC Meeting Previous Minutes Accepted 4.0 HC Roads Inverness Currently carrying out resurfacing works @ B851 – B861 then move to Inverness city centre week commencing 04/05/21. Academy Street / Chapel street – Friars lane resurfacing will commence weekend 24th April. Alex mention some conflict of works @ Drummond Road as 120m need to be done starting 05/05/21 and will continue for 5 weeks, but Allan Hog was going to defer HC works. -

Inverness Local Plan Public Local Inquiry Report- Volume 3

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 REPORT OF PUBLIC LOCAL INQUIRY INTO OBJECTIONS TO THE INVERNESS LOCAL PLAN VOLUME 3 THE HINTERLAND AND THE RURAL DEVELOPMENT AREA Reporter: Janet M McNair MA(Hons) MPhil MRTPI File reference: IQD/2/270/7 Dates of the Inquiry: 14 April 2004 to 20 July 2004 CONTENTS VOLUME 3 Abbreviations The A96 Corridor Chapter 24 Land north and east of Balloch 24.1 Land between Balloch and Balmachree 24.2 Land at Lower Cullernie Farm Chapter 25 Inverness Airport and Dalcross Industrial Estate 25.1 Inverness Airport Economic Development Initiative 25.2 Airport Safeguarding 25.3 Extension to Dalcross Industrial Estate Chapter 26 Former fabrication yard at Ardersier Chapter 27 Morayhill Chapter 28 Lochside The Hinterland Chapter 29 Housing in the Countryside in the Hinterland 29.1 Background and context 29.2 objections to the local plan’s approach to individual and dispersed houses in the countryside in the Hinterland Objections relating to locations listed in Policy 6:1 29.3 Upper Myrtlefield 29.4 Cabrich 29.5 Easter Clunes 29.6 Culburnie 29.7 Ardendrain 29.8 Balnafoich 29.9 Daviot East 29.10 Leanach 29.11 Lentran House 29.12 Nairnside 29.13 Scaniport Objections relating to locations not listed in Policy 6.1 29.14 Blackpark Farm 29.15 Beauly Barnyards 29.16 Achmony, Balchraggan, Balmacaan, Bunloit, Drumbuie and Strone Chapter 30 Objections Regarding Settlement Expansion Rate in the Hinterland Chapter 31 Local centres in the Hinterland 31.1 Beauly 31.2 Drumnadrochit Chapter 32 Key Villages in the Hinterland -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

127 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

127 bus time schedule & line map 127 Dingwall (Circular) View In Website Mode The 127 bus line (Dingwall (Circular)) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dingwall: 7:29 AM (2) Dingwall: 1:40 PM (3) Inverness: 3:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 127 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 127 bus arriving. Direction: Dingwall 127 bus Time Schedule 30 stops Dingwall Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:29 AM Bus Station, Inverness U4127, Inverness Tuesday 7:29 AM Inverness College, Longman Wednesday 7:29 AM Seaƒeld Road, Longman Thursday 7:29 AM A82, Scotland Friday 7:29 AM Kessock Bridge, Craigton Saturday Not Operational Layby, Charleston Glackmore Junction, Tore 127 bus Info Layby, Tore Direction: Dingwall Stops: 30 Windhill Road Junction, Beauly Trip Duration: 66 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Inverness, Inverness The Square, Beauly College, Longman, Seaƒeld Road, Longman, Kessock Bridge, Craigton, Layby, Charleston, Glackmore 3 High Street, Beauly Junction, Tore, Layby, Tore, Windhill Road Junction, The Square, Beauly Beauly, The Square, Beauly, The Square, Beauly, Windhill Road Junction, Beauly, Teandalloch Road 12 High Street, Beauly End, Muir Of Ord, Urray House, Muir Of Ord, Windhill Road Junction, Beauly Moorings Hotel, Muir Of Ord, Square, Muir Of Ord, Petrol Station, Muir Of Ord, Ord Arms Hotel, Muir Of Teandalloch Road End, Muir Of Ord Ord, Highƒeld Junction, Muir Of Ord, Road End, Bishop Kinkell, Station Road, Conon Bridge, Mace U2651, Muir of -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen.