Graphic Arts and Advertising As War Propaganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'immagine Dell'italia, Eredità Antica

L’immagine dell’Italia, eredità antica di Maria Grazia Maioli Archeologo Emerito della Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell’Emilia-Romagna Se chiedete a un ragazzo delle elementari o delle medie qual è la prima immagine che gli viene in mente pensando all’Italia, probabilmente vi dirà la sua forma geografica, il famoso stivale. Solo in seguito (ma non è detto) farà cenno alla figura femminile avvolta nel tricolore che compare a fumetto anche nei titoli di una famosa trasmissione televisiva. Vedere l’Italia come una persona che esiste e agisce non è al giorno d’oggi così immediato come poteva essere in altri momenti della storia patria. Manca l’abitudine all’utilizzo dei simboli e delle raffigurazioni simboliche, come è appunto la personificazione dell’Italia. Eppure la figura femminile, più o meno vestita come una donna “antica”, con la corona turrita, lo stellone in fronte e, nel caso, anche la spada, era per i nostri antenati un’immagine costantemente presente, fosse solo a livello inconscio. Compariva quasi ovunque ed era il simbolo dell’Italia, della Repubblica Italiana e quindi dell’essere Italiani: tutti sapevano che la testa turrita raffigurata un po’ dappertutto, dai francobolli alle monete, ai documenti ufficiali, rappresentava l’unione in un’unica matrice. La testa turrita è diventata il simbolo ufficiale dell’Italia solo dopo il referendum che sancì la 25 maggio 1958, Elezioni politiche fine della monarchia dei Savoia, dopo la Sulla copertina della Domenica del Corriere seconda guerra mondiale. Il simbolo non è l’Italia invita gli elettori a recarsi a votare comparso all’improvviso ma ha avuto una lunga gestazione, con variazioni nell’immagine e negli attributi che la caratterizzavano. -

Bamfords Auctioneers & Valuers

Bamfords Auctioneers & Valuers The Derby Auction House Chequers Road MILITARIA AUCTION TO MARK THE CENTENARY OF Derby THE GREAT WAR Derbyshire DE21 6EN United Kingdom Started 28 Aug 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description Medals, World War One, Pair, 46435 PTE J. FARROW S. LAN R., almost EF; John Farrow South Lancashire Regiment, also 45759 1 Royal Berkshire Regiment [2] 2 Medals, World War One, Pair, 21543 PTE T. Mc CORMICK R. LANC. R., good VF; Thomas McCormick Royal Lancashire Regiment [2] Medals, World War One, Pair, 24072 PTE C. WILLIS K.O.Y.L.I., good Very Fine; Cyril Willis King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, later 3 number 263058 [2] 4 Medals, World War One, Pair, 3/255 PTE A. C. GRACE YORKS L.I., EF; Albert C. Grace Yorkshire Light Infantry [2] 5 Medals, World War One, Pair, 166333 SPR W. CHAPLIN R.E., good Very Fine; William Chaplin [2] Medals, World War One, Pair, 49615 PTE H. BOUNDY R. LANC. R., EF; Herbert Boundy Royal Lancashire Regiment, also 112923 6 Notts & Derbys Regiment [2] 7 Medals, World War One, Pair, 22992 PTE J. GRAYSON L.N.LAN. R., EF; Joseph Grayson Loyal North Lancashire Regiment [2] Medals, World War One, 1914 Star Bar Trio, T-29561 DVR P. L. A. TAYLOR A.S.C., T. CPL on BWM and Victory, VF; Percival Taylor 8 was an Auxiliary Horse Trainer Driver, he entered the war 26th August 1914 [3] Medal, World War One, Single, British War, 5613 PTE H. COLEY LEIC R, EF; Harold Coley, 4th Battalion Leicestershire Regiment, also 9 201814 & 897058 34th Battalion London Regiment [1] Medal, World War One, Single, British War, 013737 A. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

Contrasting Portrayals of Women in WW1 British Propaganda

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 of history, propaganda has been aimed at patriarchal Victims or Vital: Contrasting societies and thus, has primarily targeted men. This Portrayals of Women in WWI remained true throughout WWI, where propaganda came into its own as a form of public information and British Propaganda manipulation. However, women were always part of Stacey Reed those societies, and were an increasingly active part History 385 of the conversations about the war. They began to be Fall 2014 targeted by propagandists as well. In war, propaganda served a variety of More than any other war before it, World War I purposes: recruitment of soldiers, encouraging social invaded the every day life of citizens at home. It was the responsibility, advertising government agendas and first large-scale war that employed popular mass media programs, vilifying the enemy and arousing patriotism.5 in the transmission and distribution of information from Various governments throughout WWI found that the the front lines to the Home Front. It was also the first image of someone pointing out of a poster was a very to merit an organized propaganda effort targeted at the effective recruiting tool for soldiers. Posters presented general public by the government.1 The vast majority of British men with both the glory of war and the shame this propaganda was directed at an assumed masculine of shirkers. Women were often placed in the role of audience, but the female population engaged with the encouraging their men to go to war. Many propaganda messages as well. -

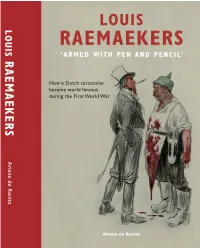

Raemaekers-EN-Cont-Intro.Pdf

LOUIS RAEMAEKERS ‘ARMED WITH PEN AND PENCIL’ How a Dutch cartoonist became world famous during the First World War Ariane de Ranitz followed by the article ‘The Kaiser in Exile: Wilhelm II in Doorn’ Liesbeth Ruitenberg Louis Raemaekers Foundation 0.Voorwerk 1-21 Engels.indd 3 17-09-14 15:57 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgments 9 4 The war: anti-neutrality 75 Introduction 13 (1914–1915) Sources 16 The first weeks of the war 75 Rumours 75 1 Youth in Roermond 23 Belgian refugees 77 (1869–1886) War reporting 79 The Raemaekers family 23 Raemaekers’ response to the German invasion 82 Conflict between liberals and clericals 24 The attitude of the Dutch press 86 Roermond newspapers 26 Raemaekers and De Telegraaf 88 Joseph Raemaekers enters the fray 28 Violation of neutrality 88 De Volksvriend closes down 30 The attitude of De Telegraaf 90 Louis learns to draw 31 First album and exhibitions 93 Cultural life dominated by the firm of Cuypers 33 More publications 98 Neutrality in danger 100 2 Training and work as drawing teacher 35 A price on Raemaekers’ head? 103 (1887–1905) Schröder goes to jail 107 Drawing training in Nijmegen, Roermond More frequent cartoons; subjects and fame 108 and Amsterdam 35 First appointment as a drawing teacher 37 5 Raemaekers becomes famous abroad 115 Departure for Brussels 38 (1915–1916) Appointment in Wageningen 38 Distribution outside the Netherlands 115 Work as illustrator and portrait painter 44 International fame 121 Marriage and children 47 London 121 Children’s books 50 Exhibition at the Fine Art Society -

Iconologia-Italia-Nelle-Monete.Pdf

L’IMMAGINE ALLEGORICA DELL’ITALIA, CHE COMPARE PER LA PRIMA VOLTA SULLE MONETE CONIATE DURANTE LA COSIDDETTA GUERRA SOCIALE (91-87 a.C.); VIENE RIPRESA NEL RISORGIMENTO COME ESPRESSIONE DELL’IDEA DI UNITA’ NAZIONA- LE. UN VIAGGIO DI OLTRE 20 SECOLI CON UN SIMBOLO CHE HA RAPPRESENTATO E RAPPRESENTA LA NOSTRA PATRIA. ICONOLOGIA ITALIA Una bellissima donna vestita d’habito sontuoso, e ricco con un manto sopra, di Gianni Graziosi* e siede sopra un globo, ha coronata la testa di torri, e di muraglie, con la de- [email protected] stra mano tiene un scettro, ovvero un’hasta, che con l’uno, e con l’altra vien dimostrata nelle sopradette Medaglie, e con la sinistra mano un cornucopia pieno di diversi frutti, e oltre ciò faremo anco, che habbia sopra la testa una bellissima stella. Italia è una parte dell’Europa, e fu chiamata prima Hesperia da Hespero fratello d’Atlante, il quale cacciato dal fratello, diè il nome, e alla Spagna , e all’Italia: ovvero fu detta Hesperia (secondo Macrobio lib. I cap. 2) dalla stella di Venere, che la sera è chiamata Hespero, per essere l’Italia sottoposta all’occaso di questa stella. Si chiamò etiandio Oenotria, ò dalla bontà del vino, che vi nasce, ò da Oenotrio, che fu re dei Sabini. Ultimamente fu detta Italia da Italo Re di Sicilia il quale insegnò a gl’italiani il modo di coltivare la terra, e vi diede anco le leggi, percioche egli venne a quella parte, dove poi regnò Turno, e la chiamò così dal suo nome, come afferma Vergilio nel lib. -

Our Lady of Antwerp

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Faculty Publications LSU Libraries 2018 Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Marty Miller Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Marty, "Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment" (2018). Faculty Publications. 79. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/libraries_pubs/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LSU Libraries at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sacred vs. Profane in The Great War: A Neutral’s Indictment Louis Raemaekers’s Use of Religious Imagery in Adoration of the Magi and Our Lady of Antwerp by Marty Miller Art and Design Librarian Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, Louisiana t the onset of the First World War in August 1914, Germany invaded France and Belgium, resulting in almost immediate British intervention and provoking a firestorm of protest throughout Western Europe. Belgium’s Asmall military was overmatched and reduced to fighting skirmishes as the Kaiser’s war machine headed toward France. Belgian civilians, as they had during the Franco- Prussian War, resisted by taking up arms. Snipers and ambushes slowed the Germans’ advance. In retaliation, German troops massacred Belgian men, women, and children. Cities, villages, and farms were burned and plundered.1 Belgian neutrality meant nothing to the German master plan to invade and defeat France before the Russian army could effectively mobilize in the east. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

World War I Posters and the Female Form

WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER Bachelor of Arts in English John Carroll University January, 2003 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTERS OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2008 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ART HISTORY and the College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Samantha Baskind _________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________ Dr. Marian Bleeke ________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Lehfeldt ___________________________ Department & Date WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER ABSTRACT Like Britain and continental Europe, the United States would utilize the poster to garner both funding and public support during World War I. While war has historically been considered a masculine endeavor, a relatively large number of these posters depict the female form. Although the use of women in American World War I visual propaganda may not initially seem problematic, upon further inspection it becomes clear that her presence often served to promote racial and national pretentiousness. Based on the works of popular pre-war illustrators like Howard Chandler Christy and Charles Dana Gibson, the American woman was the most attractive woman in the in the world. Her outstanding wit, beauty and intelligence made her the only suitable mate for the supposed racially superior American man. With the onset of war, however, the once entertaining romantic scenarios in popular monthlies and weeklies now represented what America stood to lose, and the “American Girl” would make the transition from magazine illustrations to war poster with minimal alterations. -

0123455406718954 93

worldwide delivery of jewellery and precious goods “ciò che è prezioso merita di volare alto” Ferrari Group è leader mondiale per il trasporto di merci preziose e beni di lusso. Con un’esperienza maturata in oltre 50 anni, conoscenza del mercato e delle procedure doganali, continue innovazioni nei sistemi di sicurezza, Ferrari Group oggi rappresenta un esteso network di società, sedi e uffici operativi in tutto il mondo. Il partner ideale che aggiunge valore al valore. Ferrari Group is a global leader in the worldwide shipment of precious and luxury goods. With over 50 years of experience, knowledge of markets and Customs procedures, and continuous innovation in security systems, Ferrari Group is now an extensive network of companies with branches and offices throughout the world. An ideal partner that adds value to value. the Ferrari Group: unity means strength “come spesso accade, è l’unione che fa la forza” Ferrari Group operates in all major international hubs used by producers and exporters of precious goods for their high value-added products. 80 logistic offices in 50 countries, hundreds of professionals chosen for their ability and experience, automated and integrated work procedures, vaults and vehicles that resist any emergency: a total quality system that Ferrari Group opera su tutti i principali hub internazionali che produttori ed ensures efficiency, punctuality and esportatori di preziosi utilizzano per i absolute security. loro prodotti ad alto valore aggiunto. 80 sedi logistiche distribuite in 50 paesi, centinaia di professionisti selezionati per capacità ed esperienza, procedure operative automatizzate e integrate, caveau e mezzi di trasporto a prova di qualsiasi emergenza, costituiscono un sistema di qualità totale, sinonimo di efficienza, puntualità e assoluta sicurezza. -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

'A Room of Their Own': Heritage Tourism and the Challenging of Heteropatriarchal Masculinity in Scottish National Narratives

‘A ROOM OF THEIR OWN’: HERITAGE TOURISM AND THE CHALLENGING OF HETEROPATRIARCHAL MASCULINITY IN SCOTTISH NATIONAL NARRATIVES by CARYS ATLANTA O’NEILL B.A. Furman University, 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2019 Major Professor: Amelia H. Lyons © 2019 Carys Atlanta O’Neill ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the visibility of women in traditionally masculine Scottish national narratives as evidenced by their physical representation, or lack thereof, in the cultural heritage landscape. Beginning with the 1707 Act of Union between Scotland and England, a moment cemented in history, literature, and popular memory as the beginning of a Scottish rebirth, this thesis traces the evolution of Scottish national identity and the tropes employed for its assertion to paint a clearer picture of the power of strategic selectivity and the effects of sacrifice in the process of community definition. Following the transformation of the rugged Celtic Highlander from his pre-Union relegation as an outer barbarian to his post-Union embrace as the epitome of distinction and the embodiment of anti-English, anti-aristocratic sentiment so crucial to the negotiation of a Scottish place in union and empire, this thesis hones in on notions of gender and peformative identity to form the basis for an analysis of twentieth and twenty-first century national heritage dynamics. An innovative spatial study of monuments and memorials in the Scottish capital city of Edinburgh highlights the gendered inequity of memorialization efforts and the impact of limited female visibility on the storytelling potential of the cityscape.