Arxiv:1009.3932V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

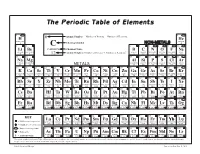

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6

COAJF- 9 50cDo/-~^0 LA-UR- 9 5-1666 Title: AGE HARDENING IN RAPIDLY SOLIDIFIED AND HOT ISOSTATICALLY PRESSED BERYLLIUM-ALUM1UM SILVER ALLOYS HVAUli Author(s): David H. Carter, MST-6 Andrew McGeorge, MST-6 Loren A. Jacobson, MST-6 llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6 IflllS,Ic 8-o° ,S8 si Proceedings of TMS Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, jJffilJSif—- Nevada, February 1995 as-IVUiS' i in Los Alamos NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is operated by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract W-7405-ENG-36. By acceptance of this article, the publisher recognizes that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or to allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. The Los Alamos National Laboratory requests that the publisher identify this article as work performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy* FotmNo.B36R5 MCTOIQimnM f\c mie hAMMr&T 10 i mi in ST26291M1 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Age Hardening in Rapidly Solidified and Hot Isostatically Pressed Beryllium-Aluminum-Silver Alloys David H. Carter, Andrew C. McGeorge,* Loren A. Jacobson, and Paul W. Stanek Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos NM 87545 Abstract Three different alloys of beryllium, aluminum and silver were processed to powder by centrifugal atomization in a helium atmosphere. Alloy com• positions were, by weight, 50% Be, 47.5% Al, 2.5% Ag, 50% Be, 47% Al, 3% Ag, and 50% Be, 46% Al, 4% Ag. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

Beryllium Compounds (A) BERYLLIUM COMPOUNDS

Beryllium Compounds (A) BERYLLIUM COMPOUNDS 107-02-8 Hazard Summary Inhalation exposure to beryllium primarily occurs in the workplaces where it is mined, processed, or converted into alloys and chemicals, or from the burning of coal or fuel oil and in tobacco smoke. Acute (short-term) inhalation exposure to high levels of beryllium has been observed to cause inflammation of the lungs or acute pneumonitis (reddening and swelling of the lungs) in humans; after exposure ends, these symptoms may be reversible. Chronic (long-term) inhalation exposure of humans to beryllium has been reported to cause chronic beryllium disease (berylliosis), in which granulomatous lesions (noncancerous) develop in the lung. Human epidemiology studies are limited, but suggest a causal relationship between beryllium exposure and an increased risk of lung cancer. Inhalation exposure to beryllium has been demonstrated to cause lung cancer in rats and monkeys. EPA has classified beryllium as a Group B1, probable human carcinogen. Please Note: The main sources of information for this fact sheet are EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) (3), which contains information on oral chronic toxicity and the RfD and inhalation chronic toxicity and the RfC, and the carcinogenic effects of beryllium including the unit cancer risk for inhalation exposure, EPA's Toxicological Review of Beryllium and Compounds (2), and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry's (ATSDR's) Toxicological Profile for Beryllium. (1) Uses Pure beryllium and its metal alloys have applications in electrical components, tools, structural components for aircraft, missiles, and satellites, and other metal-fabricating uses. (1) Beryllium is also used in consumer products, such as televisions, calculators, and personal computers. -

Unit 6 the Periodic Table How to Group Elements Together? Elements of Similar Properties Would Be Group Together for Convenience

Unit 6 The periodic table How to group elements together? Elements of similar properties would be group together for convenience. The periodic table Chemists group elements with similar chemical properties together. This gives rise to the periodic table. In the periodic table, elements are arranged according to the following criteria: 1. in increasing order of atomic numbers and 2. according to the electronic arrangement The diagram below shows a simplified periodic table with the first 36 elements listed. Groups The vertical columns in the periodic table are called groups . Groups are numbered from I to VII, followed by Group 0 (formerly called Group VIII). [Some groups are without group numbers.] The table below shows the electronic arrangements of some elements in some groups. Group I Group II Group VII Group 0 He (2) Li (2,1) Be (2,2) F (2,7) Ne (2,8) Na (2,8,1) Mg (2,8,2) Cl (2,8,7) Ar (2,8,8) K (2,8,8,1) Ca (2,8,8,2) Br (2,8,18,7) Kr (2,8,18,8) What is the relationship between the group numbers and the electronic arrangements of the elements? Group number = the number of outermost shell electrons in an atom of the element The chemical properties of an element depend mainly on the number of outermost shell electrons in its atoms. Therefore, elements within the same group would have similar chemical properties and would react in a similar way. However, there would be a gradual change of reactivity of the elements as we move down the group. -

Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds

BERYLLIUM AND BERYLLIUM COMPOUNDS Beryllium and beryllium compounds were considered by previous IARC Working Groups in 1971, 1979, 1987, and 1993 (IARC, 1972, 1980, 1987, 1993). Since that time, new data have become available, these have been incorporated in the Monograph, and taken into consid- eration in the present evaluation. 1. Exposure Data a very high strength-to-weight ratio. Beryllium is lighter than aluminium but is greater than 40% 1.1 Identification of the agents more rigid than steel. It has excellent electrical and thermal conductivities. Its only markedly Synonyms and molecular formulae for beryl- adverse feature is relatively pronounced brittle- lium, beryllium–aluminium and beryllium– ness, which restricts the use of metallic beryl- copper alloys, and certain beryllium compounds lium to specialized applications (WHO, 1990). are presented in Table 1.1. The list is not exhaus- Because of its low atomic number, beryllium tive, nor does it comprise necessarily the most is very permeable to X-rays. Neutron emission commercially important beryllium-containing after bombardment with α or γ rays is the most substances; rather, it indicates the range of beryl- important of its nuclear physical properties, lium compounds available. and beryllium can be used as a neutron source. Moreover, its low neutron absorptiveness and high-scattering cross-section make it a suitable 1.2 Chemical and physical properties moderator and reflector in structural materials of the agents in nuclear facilities; where most other metals absorb neutrons emitted during the fission Beryllium (atomic number, 4; relative atomic of nuclear fuel, beryllium atoms only reduce mass, 9.01) is a metal, which belongs to Group the energy of such neutrons, and reflect them IIA of the Periodic Table. -

Periodic Table Key Concepts

Periodic Table Key Concepts Periodic Table Basics The periodic table is a table of all the elements which make up matter Elements initially grouped in a table by Dmitri Mendeleev Symbols – each element has a symbol which is either a Capital Letter or a Capital Letter followed by a lower case letter Atomic Number – the number above an element’s symbol which shows the number of protons Atomic Mass – the number found below an elements symbol which shows the mass of the element. Mass = the number of protons + the number of neutrons Metals – the elements which have the properties of malleability, luster, and conductivity o These elements are good conductors of electricity & heat. o Found to the left of the zig-zag line on the periodic table Nonmetals – do not have the properties of metals. Found to the right of the zig-zag line Metalloids – elements found along the zig-zag line of the periodic table and have some properties of metals and nonmetals (B, Si, Ge, As, Sb, Te, and Po) Groups The columns going up and down (There are 18 groups) Group 1: Hydrogen, Lithium, Sodium, Potassium, Rubidium, Cesium, and Francium Elements arranged so that elements with similar properties would be in the same group. o Group 1 Alkali Metals - highly reactive metals o Group 2 Alkali Earth Metals – reactive metals o Group 3-12 Transition Metals o Group 17 Halogens – highly reactive non-metals o Group 18 Noble Gases - do not react or combine with any other elements. Elements are grouped according to their properties or reactivity Reactivity is determined by the number of electrons in an element’s outer energy level These electrons are called valence electrons Periods The rows that run from left to right on the periodic table (There are 7 periods) Period 1 contains 2 elements, Hydrogen and Helium. -

Chapter 3 Gamma-Ray and Neutron Sources R.J. Holmes

123 CHAPTER 3 GAMMA-RAY AND NEUTRON SOURCES R.J. HOLMES 125 1. GAMMA-RAY SOURCES Most y-ray sources in commercial use do not occur in nature because their half-lives are small compared with geological times. They must be produced from naturally occurring nuclides by a suitable nucle?r reaction; often this is by irradiation in a nuclear reactor. Some examples of radioisotope production are given below: 59Co (n,y)60Co T^ 5.26 y 123Sb (n,y)mSb T^ 60 d 6Li (n,a)3H T^ 12.3 y 55Mn (p,n)55Fe T, 2.7 y Commercially available sources are sealed in chemically inert capsules. The choice of the most suitable source for a particular application usually depends on the energy of the y-rays that are emitted and on the half-life of the radioisotope. In many applications, a monoenergetic source of long half-life is preferred. Calibration corrections for source decay can be made using the familiar equation - 0.693t/T, = Io e where I is the initial source intensity/ I(t) is its intensity at time o t, and T, is the half-life. Selection of the appropriate y-ray energy depends on such criteria as the energy threshold for a desired nuclear reaction and whether absorption should be due predominantly to the photoelectric effect or Compton scattering. Table 1 lists the commonly used y-ray sources together with their y-ray energies and half-lives. 2. X-RAY SOURCES Sources of radiation below an energy of about 150 keV are usually referred to as X-ray sources, although technically some of them are low energy y-ray sources, e.g. -

Copper Silica Feldspar Silver Gypsum Soda Ash Coal Sulfur Lead Zeolites

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 01-360 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral Resources Out of the ground...into our daily lives MINERAL COMMODITIES PRECIOUS METALS AND ELEMENTS gold platinum-group elements silver NONFERROUS METALS soda ash cobalt LIGHT METALS windows paints aluminum glassware magnets beryllium tungsten fiberglass engines magnesium detergents tools titanium lights blubs light fixtures BASE METALS iron copper stained glass faucets lead paints tools zinc silica magnets abrasive and blasting sand aluminum refrigerators ceramics IRON AND FERROALLOYS plastics automobiles glass gypsum cans chromium cobalt concrete ferroalloy metals wallboard coal tar iron manganese shampoos molybdenum vermiculite asphalt nickel feldspar tungsten fire-protection boards fluorite plates glassware toothpaste wallboard paint pigments fertilizers paper concretefill material productsbricks ceramics FERTILIZER AND asphalt sand & gravel CHEMICAL INDUSTRIAL MATERIALS limestone, dolomite, and lime lithium sulfur silver nitrogen compounds and nitrate zeolites phosphate paints photographic materials soil additives potash gold fertilizers mirrors water softeners salts rubber products wiring stereo components cat litter sulfur jewelry jewelry telephones electronic components titanium beryllium CONSTRUCTION AND MANUFACTURING white paints stereos petroleum products MATERIALS toothpaste fluorescent lights enamel finishes CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS plastics concrete products micas DDDVVD automotive parts crushed stone natural gas sand and gravel lipstick -

Beryllium Aluminium >60% Be

Substance Uses (General) Uses EEE Is this substance in use in Is substitution underway for one Quantities in use (general) Quantities in use (EEE) Do you agree with the If not, please estimate Please explain the basis Further Comments additional applications? of these applications (please provided information? Do the quantity range in for quantity usage and/or references specify with which alternative you assume the actual uses which this substance is estimations and provide chemical substance)? to be higher or lower? in use (in general references or further and/or in EEE). data if relevant Beryllium Metal (>99%Be) and High Beryllium Alloy (Beryllium Beryllium Metal and High beryllium Alloys are used in such applications in Yes Substituition is not possible. No reliable data available Approximately 2 tonnes per Information corrected by 2 -10 tonnes/yr aprox Sales figures and Aluminium >60% Be) are used in applications that require the EU as: year of beryllium are industry stakeholders 0.2 MT in EEE industry estimates. Beryllium metal combinations of : incorporated into EEE Shipments vary by applications in Europe year driven by research demands Low density (1.85 gm/cc) High Stiffness (modulus) Extreme low temperature physical properties Transparency to X-Rays Reflectivity / Moderation of neutrons Non Magnetic Highest velocity of sound / Vibration dampening capacity Applications include: • High energy physics experiment particle stream guidance beam-pipes • ITER Fusion Reactor main chamber wall lining and neutron blanket material • Medical Isotope production nuclear reactor safety and control linings • Space mounted telescope reflectors Space Exploration / Science: • Structural support in space mounted optical benches • Heat shields to protect satellites and orbital telescopes. -

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged To

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged to Four and Five Significant Figures Norman E. Holden Energy Sciences & Technology Department National Nuclear Data Center Brookhaven National Laboratory P.O. Box 5000 Upton, NY 11973-5000 www.bnl.gov Prepared for the 44th IUPAC General Assembly, in Torino, Italy August 2007 Notice: This manuscript has been authored by employees of Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The publisher by accepting the manuscript for publication acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. This preprint is intended for publication in a journal or proceedings. Since changes may be made before publication, it may not be cited or reproduced without the author’s permission. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof or its contractors or subcontractors. -

Reactive Metals Hazards Packaging

Document No: RXM20172301 Publication Date: January 23, 2017 Revised Date: October 25, 2017 Hazard Awareness & Packaging Guidelines for Reactive Metals General Due to recent events resulting from reactive metals handling, CEI personnel and clients are being updated regarding special packaging guidelines designed to protect the safety of our personnel, physical assets, and customer environments. CEI’s Materials Management staff, in conjunction with guidelines from third party disposal outlets, has approved these alternative packaging guidelines to provide for safe storage and transportation of affected materials. This protocol primarily impacts water reactive or potentially water reactive metals in elemental form, although there are many compounds that are also affected. The alkali metals are a group in the periodic table consisting of the chemical elements lithium, sodium , potassium, rubidium, cesium and francium. This group lies in the s-block of the periodic table as all alkali metals have their outermost electron in an s-orbital. The alkali metals provide the best example of group trends in properties in the periodic table, with elements exhibiting well- characterized homologous behavior. The alkali metals have very similar properties: they are all shiny, soft, highly reactive metals at standard temperature and pressure, and readily lose their outermost electron to form cations with charge +1. They can all be cut easily with a knife due to their softness, exposing a shiny surface that tarnishes rapidly in air due to oxidation. Because of their high reactivity, they must be stored under oil to prevent reaction with air, and are found naturally only in salts and never as the free element.