Unit 6 the Periodic Table How to Group Elements Together? Elements of Similar Properties Would Be Group Together for Convenience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt

An Alternate Graphical Representation of Periodic table of Chemical Elements Mohd Abubakr1, Microsoft India (R&D) Pvt. Ltd, Hyderabad, India. [email protected] Abstract Periodic table of chemical elements symbolizes an elegant graphical representation of symmetry at atomic level and provides an overview on arrangement of electrons. It started merely as tabular representation of chemical elements, later got strengthened with quantum mechanical description of atomic structure and recent studies have revealed that periodic table can be formulated using SO(4,2) SU(2) group. IUPAC, the governing body in Chemistry, doesn‟t approve any periodic table as a standard periodic table. The only specific recommendation provided by IUPAC is that the periodic table should follow the 1 to 18 group numbering. In this technical paper, we describe a new graphical representation of periodic table, referred as „Circular form of Periodic table‟. The advantages of circular form of periodic table over other representations are discussed along with a brief discussion on history of periodic tables. 1. Introduction The profoundness of inherent symmetry in nature can be seen at different depths of atomic scales. Periodic table symbolizes one such elegant symmetry existing within the atomic structure of chemical elements. This so called „symmetry‟ within the atomic structures has been widely studied from different prospects and over the last hundreds years more than 700 different graphical representations of Periodic tables have emerged [1]. Each graphical representation of chemical elements attempted to portray certain symmetries in form of columns, rows, spirals, dimensions etc. Out of all the graphical representations, the rectangular form of periodic table (also referred as Long form of periodic table or Modern periodic table) has gained wide acceptance. -

Interstellar Formamide (NH2CHO), a Key Prebiotic Precursor

Interstellar formamide (NH2CHO), a key prebiotic precursor Ana López-Sepulcre,∗,y,z Nadia Balucani,{ Cecilia Ceccarelli,y Claudio Codella,x,y François Dulieu,k and Patrice Theulé? yUniv. Grenoble Alpes, IPAG, F-38000 Grenoble, France zInstitut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM), 300 rue de la piscine, F-38406 Saint-Martin d’Hères, France {Dipartimento di Chimica, Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università degli Studi di Perugia, I-06123 Perugia, Italy xINAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, I-50125, Firenze, Italy kUniversité de Cergy-Pontoise, Observatoire de Paris, PSL University, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, LERMA, F-95000, Cergy-Pontoise, France ?Aix-Marseille Université, PIIM UMR-CNRS 7345, 13397 Marseille, France E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Formamide (NH2CHO) has been identified as a potential precursor of a wide variety arXiv:1909.11770v1 [astro-ph.SR] 25 Sep 2019 of organic compounds essential to life, and many biochemical studies propose it likely played a crucial role in the context of the origin of life on our planet. The detection of formamide in comets, which are believed to have –at least partially– inherited their current chemical composition during the birth of the Solar System, raises the question whether a non-negligible amount of formamide may have been exogenously delivered onto a very young Earth about four billion years ago. A crucial part of the effort to 1 answer this question involves searching for formamide in regions where stars and planets are forming today in our Galaxy, as this can shed light on its formation, survival, and chemical re-processing along the different evolutionary phases leading to a star and planetary system like our own. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

FRANCIUM Element Symbol: Fr Atomic Number: 87

FRANCIUM Element Symbol: Fr Atomic Number: 87 An initiative of IYC 2011 brought to you by the RACI KAYE GREEN www.raci.org.au FRANCIUM Element symbol: Fr Atomic number: 87 Francium (previously known as eka-cesium and actinium K) is a radioactive metal and the second rarest naturally occurring element after Astatine. It is the least stable of the first 103 elements. Very little is known of the physical and chemical properties of Francium compared to other elements. Francium was discovered by Marguerite Perey of the Curie Institute in Paris, France in 1939. However, the existence of an element of atomic number 87 was predicted in the 1870s by Dmitri Mendeleev, creator of the first version of the periodic table, who presumed it would have chemical and physical properties similar to Cesium. Several research teams attempted to isolate this missing element, and there were at least four false claims of discovery during which it was named Russium (after the home country of soviet chemist D. K. Dobroserdov), Alkalinium (by English chemists Gerald J. K. Druce and Frederick H. Loring as the heaviest alkali metal), Virginium (after Virginia, home state of chemist Fred Allison), and Moldavium (by Horia Hulubei and Yvette Cauchois after Moldavia, the Romanian province where they conducted their work). Perey finally discovered Francium after purifying radioactive Actinium-227 from Lanthanum, and detecting particles decaying at low energy levels not previously identified. The new product exhibited chemical properties of an alkali metal (such as co-precipitating with Cesium salts), which led Perey to believe that it was element 87, caused by the alpha radioactive decay of Actinium-227. -

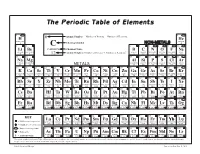

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Microdosimetry of Astatine-211 and Xa0102708 Comparison with That of Iodine-125

MICRODOSIMETRY OF ASTATINE-211 AND XA0102708 COMPARISON WITH THAT OF IODINE-125 T. UNAK Ege University, Bomova, Izmir, Turkey Abstract.' 21lAt is an alpha and Auger emitter radionuclide and has been frequently used for labeling of different kind of chemical agents. 125I is also known as an effective Auger emitter. The radionuclides which emit short range and high LET radiations such as alpha particles and Auger electrons have high radiotoxic effectiveness on the living systems. The microdosimetric data are suitable to clarify the real radiotoxic effectiveness and to get the detail of diagnostic and therapeutic application principles of these radionuclides. In this study, the energy and dose absorptions by cell nucleus from alpha particles and Auger electrons emitted by 211At have been calculated using a Monte Carlo calculation program (code: UNMOC). For these calculations two different model corresponding to the cell nucleus have been used and the data obtained were compared with the data earlier obtained for I25I. As a result, the radiotoxicity of 21lAt is in the competition with 125I. In the case of a specific agent labelled with 2I1At or 125I is incorporated into the cell or cell nucleus, but non-bound to DNA or not found very close to it, 2llAt should considerably be much more radiotoxic than i25I, but in the case of the labelled agent is bound to DNA or take a place very close to it, the radiotoxicity of i25I should considerably be higher than 21'At. 1. INTRODUCTION 21'At as an alpha and Auger emitter radionuclide has an extremely high potential application in cancer therapy; particularly, in molecular radiotherapy. -

Llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6

COAJF- 9 50cDo/-~^0 LA-UR- 9 5-1666 Title: AGE HARDENING IN RAPIDLY SOLIDIFIED AND HOT ISOSTATICALLY PRESSED BERYLLIUM-ALUM1UM SILVER ALLOYS HVAUli Author(s): David H. Carter, MST-6 Andrew McGeorge, MST-6 Loren A. Jacobson, MST-6 llfltfits Paul Stanek, MST-6 IflllS,Ic 8-o° ,S8 si Proceedings of TMS Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, jJffilJSif—- Nevada, February 1995 as-IVUiS' i in Los Alamos NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is operated by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract W-7405-ENG-36. By acceptance of this article, the publisher recognizes that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or to allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. The Los Alamos National Laboratory requests that the publisher identify this article as work performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy* FotmNo.B36R5 MCTOIQimnM f\c mie hAMMr&T 10 i mi in ST26291M1 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Age Hardening in Rapidly Solidified and Hot Isostatically Pressed Beryllium-Aluminum-Silver Alloys David H. Carter, Andrew C. McGeorge,* Loren A. Jacobson, and Paul W. Stanek Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos NM 87545 Abstract Three different alloys of beryllium, aluminum and silver were processed to powder by centrifugal atomization in a helium atmosphere. Alloy com• positions were, by weight, 50% Be, 47.5% Al, 2.5% Ag, 50% Be, 47% Al, 3% Ag, and 50% Be, 46% Al, 4% Ag. -

High-Temperature Structural Evolution of Caesium and Rubidium Triiodoplumbates D.M

High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota To cite this version: D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota. High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium tri- iodoplumbates. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, Elsevier, 2009, 69 (10), pp.2520. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007. hal-00565442 HAL Id: hal-00565442 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00565442 Submitted on 13 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Author’s Accepted Manuscript High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota PII: S0022-3697(08)00173-X DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007 Reference: PCS 5491 To appear in: Journal of Physics and www.elsevier.com/locate/jpcs Chemistry of Solids Received date: 31 January 2008 Revised date: 2 April 2008 Accepted date: 14 May 2008 Cite this article as: D.M. Trots and S.V. Myagkota, High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates, Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Systematic Approach for Chemical Reactivity

SYSTEMATIC APPROACH FOR CHEMICAL REACTIVITY EVALUATION A Dissertation by ABDULREHMAN AHMED ALDEEB Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2003 Major Subject: Chemical Engineering SYSTEMATIC APPROACH FOR CHEMICAL REACTIVITY EVALUATION A Dissertation by ABDULREHMAN AHMED ALDEEB Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________ ____________________________ M. Sam Mannan Kenneth R. Hall (Chair of Committee) (Member) ____________________________ ____________________________ Mark T. Holtzapple Jerald A. Caton (Member) (Member) ____________________________ Kenneth R. Hall (Head of Department) December 2003 Major Subject: Chemical Engineering iii ABSTRACT Systematic Approach for Chemical Reactivity Evaluation. (December 2003) Abdulrehman Ahmed Aldeeb, B.S., Jordan University of Science & Technology; M.S., The University of Texas at Arlington Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. M. Sam Mannan Under certain conditions, reactive chemicals may proceed into uncontrolled chemical reaction pathways with rapid and significant increases in temperature, pressure, and/or gas evolution. Reactive chemicals have been involved in many industrial incidents, and have harmed people, property, and the environment. Evaluation of reactive chemical hazards is critical to design and operate safer chemical plant processes. Much effort is needed for experimental techniques, mainly calorimetric analysis, to measure thermal reactivity of chemical systems. Studying all the various reaction pathways experimentally however is very expensive and time consuming. Therefore, it is essential to employ simplified screening tools and other methods to reduce the number of experiments and to identify the most energetic pathways. -

Helium Adsorption on Lithium Substrates

JLowTempPhys DOI 10.1007/s10909-007-9516-5 Helium Adsorption on Lithium Substrates E. Van Cleve · P. Taborek · J.E. Rutledge Received: 25 July 2007 / Accepted: 13 September 2007 © Springer Science+Business Media 2007 Abstract We have developed a cryogenic pulsed laser deposition (PLD) system to deposit lithium films onto a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) at 4 K. Adsorption isotherms of 4He on lithium were measured in the temperature range between 1.42 K and 2.5 K. The isotherms are qualitatively different from isotherms on strong sub- strates such as gold and weak substrates such as cesium. There is no evidence of the formation of solid-like layers of helium, and the helium coverage is approximately linear in the pressure over a wide range. By measuring the low coverage slope of the isotherms, the binding energy of helium to lithium was found to be approxi- mately −13.6 K. For lithium substrates less than approximately 100 layers thick, the chemical potential at which the superfluid transition was observed was surprisingly sensitive to the details of lithium deposition. Keywords Helium films · Pulsed laser deposition · Superfluidity · Alkali metal 1 Introduction When helium is adsorbed onto a strong heterogenous substrate such as gold, the first 2 or 3 statistical layers are solid-like. The nature of these layers is not yet clear, but the layers are amorphous and do not participate significantly in superflow at high coverages. Superfluidity on strong substrates requires a minimum critical coverage to saturate the solid-like layers, and the superfluid phase which forms at higher cover- ages flows over these layers and does not interact directly with the strong, short range This work was supported by NSF grant DMR 0509685. -

Improvement in Retention of Solid Fission Products in HTGR Fuel Particles by Ceramic Kernel Additives

FORMAL REPORT GERHTR-159 UNITED STATES-GERMAN HIGH TEMPERATURE REACTOR RESEARCH EXCHANGE PROGRAM Original report number ______________________ Title Improvement in Retention of Solid Fission Products in HTGR Fuel Particles by Ceramic Kernel Additives Authorial R. Forthmann, E. Groos and H. Grobmeier Originating Installation Kemforschtmgsanlage Juelich, West Germany. Date of original report issuance August 1975_______ Reporting period covered _ _____________________________ In the original English This report, translated wholly or in part from the original language, has been reproduced directly from copy pre pared by the United States Mission to the European Atomic Energy Community THIS REPORT MAY BE GIVEN UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION ERDA Technical Information Center, Oak Ridge, Tennessee DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. GERHTR-159 Distribution Category UC-77 CONTENTS page 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. FUNDAMENTAL STUDIES 3 3. IRRADIATION EXPERIMENT FRJ2-P17 5 3.1 Results of the Fission Product 8 Release Measurements Improvement in Retention of Solid 3.2 Electron Microprobe Investigations Fission Products in HTGR Fuel Particles 8 by Ceramic Kernel Additives. 4. IRRADIATION EXPERIMENT FRJ2-P18 16 4.1 Release of Solid Fission Products 19 4.2 Electron Microprobe Studies 24 by R. Forthmann, E. Groos, H. GrObmeier 5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 27 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 28 7. REFERENCES 29 2 - X. INTRODUCTION Kernforschungs- anlage JUTich JOL - 1226 August 1975 Considerations of the core design of advanced High-Temperature Gas-cooled GmbH IRW Reactors (HTGRs) led to increased demands concerning solid fission product retention in the fuel elements. This would be desirable not only for HTGR power plants with a helium-turbine in the primary circuit (HHT project), but also for the application of HTGRs as a source of nuclear process heat. -

Influence of Water on Conductivity of Aluminium Halide Solutions in Acetonitrile

Influence of water on conductivity of aluminium halide solutions in acetonitrile L. LUX Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Metallurgy, Technical University, CS-043 85 Košice Received 7 September 1981 Accepted for publication 8 February 1982 Equilibria of the substitution and association reactions of AICI3 and AlBr3 with acetonitrile were investigated by measuring the conductivity of solutions at varying concentrations of A1C13, AlBr3, and water in the acetonitrile solution. Both halides behave in acetonitrile in the absence of water as relatively strong electrolytes. It has been revealed that water displaces acetoni trile from the solvate sphere of cation of both halides. As for AlBr3, the bromide ion is also displaced from the coordination sphere of aluminium and replaced by a neutral water molecule, which simultaneously results in an increased number of ionized particles in solution. The hydrate A1X3 -6H20 was identified as final product which separates from the solution by adding water. Изучены равновесия реакций замещения и ассоциации А1С13 и А1Вг3 с ацетонитрилом посредством измерения электропроводности раствора в зависимости от концентрации А1С13, А1Вг3, как и в зависимости от концентрации воды в растворе ацетонитрила. Оба галогенида ведут себя в ацетонитриле как сравнительно сильные электролиты в отсутствии воды. Обнаружено, что вода вытесняет ацетонитрил из сольватной обо лочки катиона у обоих галогенидов. У А1Вг3 доходит и к вытеснению иона брома из координационной сферы алюминия и его замещению нейтраль ной молекулой воды, что одновременно приводит к увеличению числа ионизированных частиц в растворе. Конечным продуктом, выделенным из раствора при добавлении воды был идентифицированный гидрат А1Х3-6Н20. Acetonitrile is a typical aprotic solvent which is widely used in electrochemical research because of its profitable properties, i.e.