Alsace in France's Ancien Régime Mark A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mass, Ever Ancient, Ever New Part

The Mass, Ever Ancient, Ever New explanations of the Mass, including Latin-English missals, became commonplace. In the twentieth Part One century Pope St. Pius X promoted frequent By Fr. Edward Horkan Communion, lowered the age of First Communion This article describes the background and rationale for the to seven, and encouraged more participation in new translation of the Mass. I will give a more lengthy singing during the Mass. In the 1947 encyclical explanation of the individual changes this Wednesday, Mediator Dei, Pope Pius XII also encouraged more November 16 at 7:30, in Heller Hall with an opportunity popular participation in the Mass, avoiding either for questions and answers afterward. routineness or an excessive showiness more fitted to entertainment than timeless worship. When Blessed In the liturgies of the Church and especially in the John XXIII launched the Second Vatican Council, its Mass, “we take part in the beginning of the heavenly first document was Sacrosanctum Concilium, which liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of called for a full and active participation of the people Jerusalem toward which we journey as pilgrims.” So in the liturgy. In particular, the Council document declared Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Vatican II promoted reforms along four main lines: (1) more of Council’s constitution on the liturgy. The words of a noble simplicity; (2) a broader scope of scriptural liturgies should help us sense this heavenly company readings; (3) more emphasis on homilies and and their joy in the worship of God. The basic instruction; and (4) the increased use of vernacular elements of the Mass are fixed, but the specific words languages, although Latin was to be preserved. -

Social and Solidarity Economy: Challenges and Opportunities for Today’S Entrepreneurs

Social and Solidarity Economy: Challenges and Opportunities for Today’s Entrepreneurs UNITEE Strasbourg, 21st March 2014 The European-Turkish Business Confederation (UNITEE) represents, at the European level, entrepreneurs and business professionals with a migrant background (New Europeans). Their dual cultural background and their entrepreneurial spirit present a central asset which can facilitate Europe’s economic growth. FEDIF Grand Est is the Federation of French-Turkish Entrepreneurs of the French Great East region. It represents trade and industry entrepreneurs of the East of France. The first objective of FEDIF Grand Est is to contribute to the economic development of the region by promoting entrepreneurship and supporting the regional enterprises. CONFERENCE REPORT On Friday, 21st March 2014, UNITEE and FEDIF Grand Est organised the panel discussion “Social and Solidarity Economy: Challenges and Opportunities for Today’s Entrepreneurs” in UNITEE’s Strasbourg Office. Catherine Trautmann, MEP, and Pierre Roth, Managing Director of the Regional Chamber of the Social and Solidarity Economy of Alsace, were invited to this event to discuss the topic of social and solidarity economy (SSE), a major issue in the context of economic crisis. SPEAKERS Moderator: Mme Camille Serres, Project Manager Catherine Trautmann, MEP, Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Pierre Roth, Managing Director of the Regional Chamber of the Social and Solidarity Economy of Alsace (CRESS Alsace) 2 CONFERENCE REPORT Aburahman Atli, Secretary General of FEDIF Grand Est and head of UNITEE’s Strasbourg Office, opened the conference with a welcome speech in which he underlined the challenges and opportunities of this new form of economy in our worrying economic climate. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols. -

Perspectives on World History Change and Continuity 2

CHAPTER Perspectives on World History Change and Continuity 2 hree miles west of the modern city of Córdoba, Spain, lies the buried city Tof Medina Azahara. Constructed in the tenth century, Medina Azahara was the political and cultural hub of the Islamic kingdom of al-Andalus, the Arabic name for the Iberian Peninsula (current-day Spain and Portugal). There was nothing in Europe to compare to it. It was, in the words of a current scholar of that period, “like New York versus, well, a rural village in Mexico.”1 The Islamic world, not Christian Europe, was the center of the universe. Today, even though excavations began in 1910, only about 10 percent of the buried city has been Our identity comes in part from history, sometimes buried right beneath our feet, as in the case depicted here of the ancient Muslim city of Medina Azahara in southern Spain. Ninety uncovered and restored. Now, the site is percent of this Islamic metropolis remains unexcavated. threatened by urban sprawl and the vagaries of government funding to preserve the ruins. Too few people know about it and care to preserve it. Yet this history, however ancient, constitutes the basis of our global political heritage. It is worth studying to gain insights about our contemporary world. How we view this history, of course, depends on our perspective. The realist perspective looks at world history through the lens of power distribution. It sees a dynamic of two major configurations of power over the past 5,000 years: empire and equilibrium. These two configurations cycled back and forth, as empires consolidated dominant power and smaller powers resisted to reestablish equilibrium. -

Blue Header Photo Company Newsletter

D E C E M B E R 2 0 1 9 CHOOSE ECORHENA! choose France and the Franco-German cooperation! choose Grand Est and the Rhine territory! A MULTI-PARTNER PROJECT, A CULTURE OF WITH A FRANCO-GERMAN AND PRODUCTIVITY EUROPEAN ANCHORING At the heart of Europe, along the Rhine At the center of Europe's "blue banana" In the context of the shutting down of the nuclear power plant of Where Latin and German Fessenheim in 2020, 13 entities signed the territory project, including 5 worlds meet and merge German ones : the German authorities are involved in the Ecorhéna Historic crossroads for trade development project, and in the whole territory project. and culture Most European cities and The European Commission visited us last March, and announced that it capitals within 1,5 hour flight will come back to explore how best to support this project. Exceptional European fundings have already been made available for actions within the territory project. Ecorhéna development is already conducted in project mode: all the public-private partners are committed to the development of the territory. 90HA TAILOR-MADE, INCLUDING 30HA ALREADY AVAILABLE Total flexibility : the area can be set up in accordance with your exact specifications. All the schedule for the greenfield is planned at the same timeline as your project, so the greenfield will perfectly fit your plans. No delay : all procedures for the area are performed in parallel with potential ICPE (rgulation for protection of the environment) procedure. Compulsory environmental studies (« études faune- flore ») are already finalized, and their official report available. -

Soufflenheim Jewish Records

SOUFFLENHEIM JEWISH RECORDS Soufflenheim Genealogy Research and History www.soufflenheimgenealogy.com There are four main types of records for Jewish genealogy research in Alsace: • Marriage contracts beginning in 1701. • 1784 Jewish census. • Civil records beginning in 1792. • 1808 Jewish name declaration records. Inauguration of a synagogue in Alsace, attributed to Georg Emmanuel Opitz (1775-1841), Jewish Museum of New York. In 1701, Louis XIV ordered all Jewish marriage contracts to be filed with Royal Notaries within 15 days of marriage. Over time, these documents were registered with increasing frequency. In 1784, Louis XVI ordered a general census of all Jews in Alsace. Jews became citizens of France in 1791 and Jewish civil registration begins from 1792 onwards. To avoid problems raised by the continuous change of the last name, Napoleon issued a Decree in 1808 ordering all Jews to adopt permanent family names, a practice already in use in some places. In every town where Jews lived, the new names were registered at the Town Hall. They provide a comprehensive census of the French Jewish population in 1808. Keeping registers of births, marriage, and deaths is not part of the Jewish religious tradition. For most people, the normal naming practice was to add the father's given name to the child's. An example from Soufflenheim is Samuel ben Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel or Hindel bat Eliezer whose father is Eliezer ben Samuel (ben = son of, bat = daughter of). Permanent surnames were typically used only by the descendants of the priests (Kohanim) and Levites, a Jewish male whose descent is traced to Levi. -

Pronunciation Dictionaries for the Alsatian Dialects to Analyze Spelling and Phonetic Variation

Pronunciation Dictionaries for the Alsatian Dialects to Analyze Spelling and Phonetic Variation Lucie Steiblé, Delphine Bernhard LiLPa, Université de Strasbourg, France [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article presents new pronunciation dictionaries for the under-resourced Alsatian dialects, spoken in north-eastern France. These dictionaries are compared with existing phonetic transcriptions of Alsatian, German and French in order to analyze the relationship between speech and writing. The Alsatian dialects do not have a standardized spelling system, despite a literary history that goes back to the beginning of the 19th century. As a consequence, writers often use their own spelling systems, more or less based on German and often with some specifically French characters. But none of these systems can be seen as fully canonical. In this paper, we present the findings of an analysis of the spelling systems used in four different Alsatian datasets, including three newly transcribed lexicons, and describe how they differ by taking the phonetic transcriptions into account. We also detail experiments with a grapheme-to-phoneme (G2P) system trained on manually transcribed data and show that the combination of both spelling and phonetic variation presents specific challenges. Keywords: Alsatian, transcription, spelling variation 1. Introduction • We train and evaluate a G2P system based on the man- The Alsatian dialects, which belong to the High German di- ual transcriptions. alects, are still spoken by approximately 500,000 speakers in Alsace, a region in north-eastern France (INSEE et al., 2. Related Work 1999). Being non-dominant varieties, in a French-speaking Spelling variation is an issue for many different applica- country, they are mostly considered as oral languages, and tions which have to process texts lacking spelling con- have no standardized spelling system. -

Extended Briefing Paper

ECCLESIA DEI DELFT Extended Briefing Paper on the CDF Questionnaire to Local Ordinaries on the Extraordinary Form of the Mass concerning the Implementation of the Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum in the Netherlands, 2020 Member of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce EXTENDED BRIEFING PAPER ON THE CDF QUESTIONNAIRE 2 TO LOCAL ORDINARIES ON THE APPLICATION OF THE MOTU PROPRIO SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM 2020 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Archdiocese Utrecht ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Diocese Haarlem-Amsterdam ............................................................................................................................ 12 Diocese Rotterdam ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Diocese Breda .................................................................................................................................................... 21 Diocese Den Bosch (s’-Hertogenbosch) ............................................................................................................. 24 Diocese Roermond -

Les Naissances Illégitimes En Alsace

les familles d’aujourd’hui Séminaire de Genève (17-20 septembre 1984) ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE DES DÉMOGRAPHES DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE A I D E L F AIAIDELF. 1986. Les familles d’aujourd’hui - Actes du colloque de Genève, septembre 1984, Association internationale des démographes de langue française, ISBN : 2-7332-7009-5, 600 pages. LES NAISSANCES ILLEGITIMES EN ALSAC E Marie-Noëlle DENIS (Centre National del a Recherch e Scientifique, Strasbourg, France) INTRODUCTION L'évolution des naissances illégitimes constitue, en soit ete n liaison avec les progrè s del a contraception etd ed e l'avortement, unbo n indice des comportement s deno s sociétés vis-à-vis del a famille tradition nelle et cett e remise en caus e du mariag e révèle, àl a fois , des modifica tions du système économique etde s bouleversement s de mentalités . L'Alsace présente àce s deux points devu eu n gran d intérêt, puis qu'il s'agit d'une région industrialisée dèsl e milie u du XIXèm e siècle, où trois religions officielles, solidement implantées, ont défend u la famill e comme cellule de bas e de notr e société. I -L E CONSTA T DES FAIT S Si l'on observe , e n effet , l'évolution des naissance s illégitimes e n Alsace depuis le milie u du XVIIIème siècle, on constate tout d'abord que celle-ci est soumis e à deu x types de variation s : 1)de s variation s de faibl e amplitude etd e longu e durée, 2) des variations beaucoup plus importantes, mais très limitées dans le temps. -

Alsace and Its Language

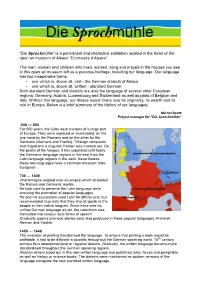

“Die Sproch mühle” is a permanent and interactive exhibition located in the heart of the open air museum of Alsace “Ecomusée d’Alsace”. The men, women and children who lived, worked, sang and prayed in the houses you see in this open air museum left us a precious heritage, including our language. Our language has two inseparable forms: • one which is, above all, oral - the German dialects of Alsace • one which is, above all, written - standard German Both standard German and dialects are also the language of several other European regions: Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland as well as parts of Belgium and Italy. Without this language, our Alsace would finally lose its originality, its wealth and its role in Europe. Below is a brief summary of the history of our languages. Michel Bentz Project manager for “Die Sproch mühle“ -500 — 800 For 500 years, the Celts were masters of a large part of Europe. They were replaced or assimilated, on the one hand by the Romans and on the other by the Germans (Alemans and Franks). Through conquests and migrations a linguistic frontier was marked out. On the peaks of the Vosges, it has separated until today the Germanic language regions in the east from the Latin language regions in the west. Nevertheless, these two languages have a common ancestor: Indo- European. 700 — 1400 Charlemagne reigned over an empire which straddled the Roman and Germanic worlds. He took care to preserve the Latin language while ensuring the promotion of popular languages. He and his successors used Latin for official acts, but recommended to priests that they should speak to the people in their native tongues. -

ALSACE-LORRAINE and Its Recovery

1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OP ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery WI.1M AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE-LORRAINE and its Recovery 1870 & 1914 THE ANNEXATION OF ALSACE=LORRA1NE and its Recovery WITH AN ADDRESS BY MARSHAL JOFFRE PARIS IMPRIMERIE JEAN CUSSAC 40 — RUE DE REUILLY — 40 I9I8 ADDRESS in*" MARSHAL JOFFRE AT THANN « WE HAVE COME BACK FOR GOOD AND ALL : HENCEFORWARD YOU ARE AND EVER WILL BE FRENCH. TOGETHER WITH THOSE LIBERTIES FOR WHICH HER NAME HAS STOOD THROUGHOUT THE AGES, FRANCE BRINGS YOU THE ASSURANCE THAT YOUR OWN LIBERTIES WILL BE RESPECTED : YOUR ALSATIAN LIBER- TIES, TRADITIONS AND WAYS OF LIVING. AS HER REPRESENTATIVE I BRING YOU FRANCE'S MATERNAL EMBRACE. » INTRODUCTION The expression Alsace-Lorraine was devis- ed by the Germans to denote that part of our national territory, the annexation of which Germany imposed upon us by the treaty of Frankfort, in 1871. Alsace and Lorraine were the names of two provinces under our monarchy, but provinces — as such — have ceased to exi$t in France since 1790 ; the country is divided into depart- ments — mere administrative subdivisions under the same national laws and ordi- nances — nor has the most prejudiced his- torian ever been able to point to the slight- est dissatisfaction with this arrangement on the part of any district in France, from Dunkirk to Perpignan, or from Brest to INTRODUCTION Strasbourg. France affords a perfect exam- ple of the communion of one and all in deep love and reverence for the mother-country ; and the history of the unfortunate depart- ments subjected to the yoke of Prussian militarism since 1871 is the most eloquent and striking confirmation of the justice of France's demand for reparation of the crime then committed by Germany.