Phd Thesis Noel Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxoffice Records: Season 1937-1938 (1938)

' zm. v<W SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL JANET DOUGLAS PAULETTE GAYNOR FAIRBANKS, JR. GODDARD in "THE YOUNG IN HEART” with Roland Young ' Billie Burke and introducing Richard Carlson and Minnie Dupree Screen Play by Paul Osborn Adaptation by Charles Bennett Directed by Richard Wallace CAROLE LOMBARD and JAMES STEWART in "MADE FOR EACH OTHER ” Story and Screen Play by Jo Swerling Directed by John Cromwell IN PREPARATION: “GONE WITH THE WIND ” Screen Play by Sidney Howard Director, George Cukor Producer DAVID O. SELZNICK /x/HAT price personality? That question is everlastingly applied in the evaluation of the prime fac- tors in the making of motion pictures. It is applied to the star, the producer, the director, the writer and the other human ingredients that combine in the production of a motion picture. • And for all alike there is a common denominator—the boxoffice. • It has often been stated that each per- sonality is as good as his or her last picture. But it is unfair to make an evaluation on such a basis. The average for a season, based on intakes at the boxoffices throughout the land, is the more reliable measuring stick. • To render a service heretofore lacking, the publishers of BOXOFFICE have surveyed the field of the motion picture theatre and herein present BOXOFFICE RECORDS that tell their own important story. BEN SHLYEN, Publisher MAURICE KANN, Editor Records is published annually by Associated Publica- tions at Ninth and Van Brunt, Kansas City, Mo. PRICE TWO DOLLARS Hollywood Office: 6404 Hollywood Blvd., Ivan Spear, Manager. New York Office: 9 Rockefeller Plaza, J. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin

Notes Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin 1. In terms of terminology, ‘folk tales’ are the orally distributed narratives disseminated in ‘premodern’ times, and ‘fairy tales’ their literary equiva- lent, which often utilise related themes, albeit frequently altered. The term ‘ wonder tale’ was favoured by Vladimir Propp and used to encompass both forms. The general absence of any fairies has created something of a mis- nomer yet ‘fairy tale’ is so commonly used it is unlikely to be replaced. An element of magic is often involved, although not guaranteed, particularly in many cinematic treatments, as we shall see. 2. Each show explores fairy tale features from a contemporary perspective. In Grimm a modern-day detective attempts to solve crimes based on tales from the brothers Grimm (initially) while additionally exploring his mythical ancestry. Once Upon a Time follows another detective (a female bounty hunter in this case) who takes up residence in Storybrooke, a town populated with fairy tale characters and ruled by an evil Queen called Regina. The heroine seeks to reclaim her son from Regina and break the curse that prevents resi- dents realising who they truly are. Sleepy Hollow pushes the detective prem- ise to an absurd limit in resurrecting Ichabod Crane and having him work alongside a modern-day detective investigating cult activity in the area. (Its creators, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, made a name for themselves with Hercules – which treats mythical figures with similar irreverence – and also worked on Lost, which the series references). Beauty and the Beast is based on another cult series (Ron Koslow’s 1980s CBS series of the same name) in which a male/female duo work together to solve crimes, combining procedural fea- tures with mythical elements. -

Annual Report 2019/20

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 G19 REPORT OF THE NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION for the year ended 30 June 2020 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June 2020. Kerry Prendergast David Wright CHAIR BOARD MEMBER Image: Daniel Cover Image: Bellbird TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION COVID-19 Our Year in Review ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 The screen industry faced unprecedented disruption in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. At the time the country moved to Alert Level 4, 47 New Zealand screen productions were in various stages Chair’s Introduction •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 of production: some were near completion and already scheduled for theatrical release, some in post-production, many in production itself and several with offers of finance gearing up for CEO Report •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 pre-production. Work on these projects was largely suspended during the lockdown. There were also thousands of New Zealand crew working on international productions who found themselves NZFC Objectives/Medium Term Goals •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 without work while waiting for production to recommence. NZFC's Performance Framework ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 COVID-19 also significantly impacted the domestic box office with cinema closures during Levels Vision, Values and Goals ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 9 3 and 4 disrupting the release schedule and curtailing the length of time several local features Activate high impact, authentic and culturally significant Screen Stories ••••••••••••• 11 played in cinemas. -

Yahoo! Movies: Brown Sugar

TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX LINE-UP Date Titre Genre Réalisateur Cast 2019 Matt Bettinelli-Olpin Samara Weaving, Andie MacDowell, Mark O'Brien, Adam 28-août-19 WEDDING NIGHTMARE Horreur Tyler Gillett Brody Thriller Brad Pitt, Tommy Lee Jones, Donald Sutherland, 2-oct.-19 AD ASTRA James Gray Science Fiction Ruth Negga 23-oct.-19 TERMINATOR : DARK FATE Science-Fiction Tim Miller Linda Hamilton, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gabriel Luna Comédie 30-oct.-19 STUBER Michael Dowse Dave Bautista, Kumail Nanjiani Action LE MANS 66 Action, 13-nov.-19 James Mangold Matt Damon, Christian Bale (FORD V FERRARI) Biographie 27-nov.-19 THE WOMAN IN THE WINDOW Drame/ Thriller Joe Wright Amy Adams, Julianne Moore, Wyatt Russell, Gary Oldman 4-déc.-19 THE ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN Drame Simon Curtis Amanda Seyfield, Milo Ventimiglia, Gary Cole LES INCOGNITOS Nick Bruno 25-déc.-19 Animation (Spies in Disguise) & Troy Quane Date Titre Genre Réalisateur Cast 2020 8-janv.-20 UNDERWATER Action/Drame William Eubank Kristen Stewart, T.J. Miller, Vincent Cassel Roman Griffin Davis, Thomasin McKenzie, Taika Waititi, Sam 22-janv.-20 JOJO RABBIT Drame Taika Waititi Rockwell, Scarlett Johansson 12-févr.-20 KING'S MAN Action/Aventure Matthew Vaughn 19-févr.-20 THE CALL OF THE WILD Aventure/Drame Chris Sanders Harrison Ford, Dan Stevens, Colin Woodell, Omar Sy Blu Hunt, Charlie Heaton, Maisie Williams,Henry Zaga, 1-avr.-20 NEW MUTANTS Action/ Aventure Josh Boone Anya Taylor-Joy 1-juil.-20 FREE GUY Action/ Aventure Shawn Levy Ryan Reynolds 22-juil.-20 BOB'S BURGER Animation 7-oct.-20 DEATH ON THE NILE Drame/Thriller Kenneth Branagh Kenneth Branagh 28-oct.-20 RON'S GONE WRONG Animation 16-déc.-20 WEST SIDE STORY Musical Steven Spielberg Ansel Elgort, Rita Moreno, Corey Stoll 2021 3-mars-21 NIMONA Animation 15-déc.-21 AVATAR 2 - 3D James Cameron 2023 20-déc.-23 AVATAR 3 - 3D James Cameron 2025 17-déc.-25 AVATAR 4 -3D James Cameron 2027 15-déc.-27 AVATAR 5 - 3D James Cameron A DATER A DATER GAMBIT Action/ Aventure Channing Tatum A DATER FOSTER Animation. -

Directed by Henry Selick; Based on the Novel by Neil Gaiman

Directed by Henry Selick; Based on the novel by Neil Gaiman Production Notes 2 Table of Contents I. Synopsis page 3 II. The Genesis of Coraline page 4 III. Screen Vision page 6 IV. Stop Starts page 7 V. With the Voice Talents of… page 9 VI. Two Worlds, One Studio page 14 VII. On the Set page 23 VIII. Two Worlds, Three Dimensions page 24 IX. Fast Facts page 27 X. Trivia Tips page 28 XI. About the Cast page 29 XII. About the Moviemakers page 33 3 Synopsis Combining the visionary imaginations of two premier fantasists, director Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas) and author Neil Gaiman (Sandman), Coraline is a wondrous and thrilling, fun and suspenseful adventure that honors and redefines two moviemaking traditions. It is a stop-motion animated feature – and, as the first one to be conceived and photographed in stereoscopic 3-D, unlike anything moviegoers have ever experienced before. Coraline Jones (voiced by Dakota Fanning) is a girl of 11 who is feisty, curious, and adventurous beyond her years. She and her parents (Teri Hatcher, John Hodgman) have just relocated from Michigan to Oregon. Missing her friends and finding her parents to be distracted by their work, Coraline tries to find some excitement in her new environment. She is befriended – or, as she sees it, is annoyed – by a local boy close to her age, Wybie Lovat (Robert Bailey Jr.); and visits her older neighbors, eccentric British actresses Miss Spink and Forcible (Jennifer Saunders and Dawn French) as well as the arguably even more eccentric Russian Mr. -

When Kerry Met Sally: Politics and Perceptions in the Demand for Movies

When Kerry Met Sally: Politics and Perceptions in the Demand for Movies∗ Jason M.T. Roos† Ron Shachar‡ September 4, 2013 Abstract Movie producers and exhibitors make various decisions requiring an understanding of moviegoer’s preferences at the local level. Two examples of such decisions are exhibitors’ allocation of screens to movies, and producers’ allocation of advertising across different regions of the country. This study presents a predictive model of local demand for movies with two unique features. First, arguing that consumers’ political tendencies have unutilized predictive power for marketing models, we allow consumers’ heterogeneity to depend on their voting tendencies. Second, instead of using the commonly used genre classifications to characterize movies, we estimate latent movie attributes. These attributes are not determined a priori by industry professionals, but rather reflect consumers’ perceptions, as revealed by their movie-going behavior. Box-office data over five years from 25 counties in the U.S. Midwest provide support for the model. First, consumers’ preferences are related to their political tendencies. For example, we find that counties that voted for congressional Republicans prefer movies starring young, white, female actors over those starring African-American, male actors. Second, perceived attributes provide new insights into con- sumers’ preferences. For example, one of these attributes is the movie’s degree of seriousness. Finally and most importantly, the two improvements proposed here have a meaningful impact on forecasting error, decreasing it by 12.6 percent. ∗Our thanks go to Preyas Desai, Ron Goettler, Joel Huber, Wagner Kamakura, Carl Mela, Rick Staelin, and Andrew Sweeting who were kind enough to share some of their expertise. -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

In Brief Law School Publications

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons In Brief Law School Publications 2016 In Brief Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief Recommended Citation In Brief, iss. 99 (2016). https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in In Brief by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. FALL 2016 ISSUE 99 InTHE MAGAZINE OF CASE Brief WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW THE CHANGING FACE OF LAW EMPLOYMENT ALUMNI USE THEIR LAW DEGREES TO PURSUE UNIQUE CAREER PATHS CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS 6 U.S. News names CWRU a top innovator, The Changing Face of Rankings improve for third straight year 7 Seven law students sweep top national and international awards 33 New mural showcases Cleveland — Law Employment and collaboration ALUMNI USE THEIR LAW DEGREES TO PURSUE UNIQUE CAREER PATHS 34 NOTABLE MILESTONES: Frederick K. Cox International Law Center celebrates 25th year anniversary 10 The Paths Not Taken 36 The Lawyerette of the ’70s Faced with a dramatically altered legal marketplace, law school graduates are 38 Society of Benchers 2016 increasingly blazing trails in exciting new arenas 66 Honor Roll of Donors 14 Robert Triozzi ‘82 returns to public interest roots as Cuyahoga County’s newest Law Director 16 Mark Griffin ‘94 returns for second term -

Click to Download

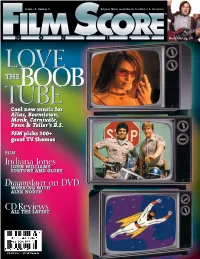

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress.