Sefer Hashiva Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

Understanding Mikvah

Understanding Mikvah An overview of Mikvah construction Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi S. Z. Lesches permission & comments: (514) 737-6076 4661 Van Horne, Suite 12 Montreal P.Q. H3W 1H8 Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Lesches, Schneur Zalman Understanding mikvah : an overview of mikvah construction ISBN 0-9689146-0-8 1. Mikveh--Design and construction. 2. Mikveh--History. 3. Purity, Ritual--Judaism. 4. Jewish law. I. Title. BM703.L37 2001 296.7'5 C2001-901500-3 v"c CONTENTS∗ FOREWORD .................................................................... xi Excerpts from the Rebbe’s Letters Regarding Mikvah....13 Preface...............................................................................20 The History of Mikvaos ....................................................25 A New Design.............................................................27 Importance of a Mikvah....................................................30 Building and Planning ......................................................33 Maximizing Comfort..................................................34 Eliminating Worry ......................................................35 Kosher Waters ...................................................................37 Immersing in a Spring................................................37 Oceans..........................................................................38 Rivers and Lakes .........................................................38 Swimming Pools .........................................................39 -

Lulav-And-Etrog-Instructions.Pdf

אֶּתְ רֹוג לּולָב LULAV AND ETROG: THE FOUR SPECIES What they are and what to do with them INTRODUCTION The commandment regarding the four species (of the lulav and etrog) is found in the Torah. After discussing the week-long Sukkot festival, specific instructions for how to celebrate the holiday are given. Leviticus 23:40 instructs: םּולְקַחְתֶּ לָכֶּם בַּיֹוםהָרִ אׁשֹון פְרִ י עֵץ הָדָרכַפֹּת תְ מָרִ ים וַעֲנַף עֵץ־עָבֹּת וְעַרְ בֵי־נָחַל ּושְ מַחְתֶּ ם לִפְ נֵי ה' אֱֹלהֵיכֶּם ׁשִבְ עַת יָמִ ים “On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before Adonai your God seven days." These are the four species that form the lulav and etrog. The four species are waved in the synagogue as part of the service during the holiday of Sukkot. Traditionally, they are not waved on Shabbat because bringing these items to the synagogue would violate the prohibition against carrying. Some liberal synagogues do wave the lulav and etrog on Shabbat. While it is customary for each individual to have a lulav and etrog, many synagogues leave some sets in the synagogue sukkah for the use of their members. The lulav and etrog may also be waved at home. Below you will find some basic information about the lulav and etrog, reprinted with permission from The Jewish Catalogue: A Do-It-Yourself Kit, edited by Richard Siegel, Michael Strassfeld and Sharon Strassfeld, published by the Jewish Publication Society. HOW THE FOUR PARTS FIT TOGETHER The lulav is a single palm branch and occupies the central position in the grouping. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

Torah: Covenant and Constitution

Judaism Torah: Covenant and Constitution Torah: Covenant and Constitution Summary: The Torah, the central Jewish scripture, provides Judaism with its history, theology, and a framework for ethics and practice. Torah technically refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). However, it colloquially refers to all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh. Torah is the one Hebrew word that may provide the best lens into the Jewish tradition. Meaning literally “instruction” or “guidebook,” the Torah is the central text of Judaism. It refers specifically to the first five books of the Bible called the Pentateuch, traditionally thought to be penned by the early Hebrew prophet Moses. More generally, however, torah (no capitalization) is often used to refer to all of Jewish sacred literature, learning, and law. It is the Jewish way. According to the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Torah is God’s blueprint for the creation of the universe. As such, all knowledge and wisdom is contained within it. One need only “turn it and turn it,” as the rabbis say in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 5:25, to reveal its unending truth. Another classical rabbinic image of the Torah, taken from the Book of Proverbs 3:18, is that of a nourishing “tree of life,” a support and a salve to those who hold fast to it. Others speak of Torah as the expression of the covenant (brit) given by God to the Jewish people. Practically, Torah is the constitution of the Jewish people, the historical record of origins and the basic legal document passed down from the ancient Israelites to the present day. -

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

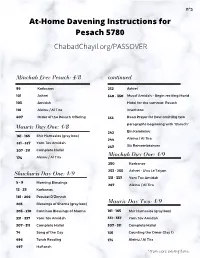

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

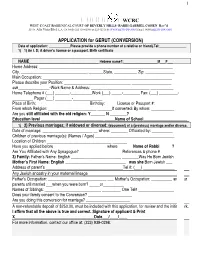

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

A Guide to Our Shabbat Morning Service

Torah Crown – Kiev – 1809 Courtesy of Temple Beth Sholom Judaica Museum Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Assistant Rabbi Cantor Cecelia Beyer Ofer S. Barnoy Ritual Director Executive Director Rabbi Sidney Solomon Donna Bartolomeo Director of Lifelong Learning Religious School Director Gila Hadani Ward Sharon Solomon Early Childhood Center Camp Director Dir.Helayne Cohen Ginger Bloom a guide to our Endowment Director Museum Curator Bernice Cohen Bat Sheva Slavin shabbat morning service 401 Roslyn Road Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 Phone 516-621-2288 FAX 516- 621- 0417 e-mail – [email protected] www.tbsroslyn.org a member of united synagogue of conservative judaism ברוכים הבאים Welcome welcome to Temple Beth Sholom and our Shabbat And they came, every morning services. The purpose of this pamphlet is to provide those one whose heart was who are not acquainted with our synagogue or with our services with a brief introduction to both. Included in this booklet are a history stirred, and every one of Temple Beth Sholom, a description of the art and symbols in whose spirit was will- our sanctuary, and an explanation of the different sections of our ing; and they brought Saturday morning service. an offering to Adonai. We hope this booklet helps you feel more comfortable during our service, enables you to have a better understanding of the service, and introduces you to the joy of communal worship. While this booklet Exodus 35:21 will attempt to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and service, it cannot possibly anticipate all your questions. Please do not hesitate to approach our clergy or regular worshipers with your questions following our services. -

Friday, September 13, 2019 at 7:30Pm

We recall those recently departed: Jerome Solomon, father of Barbara Harris Martin Jaffe, father of Jillian Rauer Leah Goodwin, mother of Richard Goodwin Serve God with gladness! Come into God's presence with singing Lorraine Rogowitz-Black, mother of Bernice Rogowitz Psalm100 Sidney Smolowitz, father of Janice Smolowitz מַ ה יַפֶה הַ יוֹם Mah Yafeh Hayom We remember, with gratitude, this American Soldier who Text from Shabbat z’mirah Music: Noam Katz and Michael Mason September 13 –14, 2019 recently gave his life: 14 Elul 5779 מַ ה יַפֶה הַ יוֹם, שַׁבָּ ת שָׁ לוֹם. .Mah ya-feh ha-yom, Sha-bat shalom Sgt. 1st Class Elis A. Barreto Oritz 34 of Morovis, Puerto Rico How lovely is this day of Shabbat peace. 7:30pm We remember, with love, the Six Million Ki Teitzei whose lives were taken during the Holocaust. Am I Awake/Barechu We also remember, with love, those who were taken Noah Aronson from our midst this week in years past and commemorate the anniversaries of their passing. Yai-lai lai lai lai… Rabbi David K. Holtz Week of September 8 -14, 2019 Am I awake? Cantor Margot E.B. Goldberg Am I prepared? Mirla Biderman Phyllis Latz Are you listening to my prayer? Executive Director Stuart P. Skolnick * Louis Caplan * Lena Levinsky Can you hear my voice? Director Of Education Yanira Quinones * Al Cooper Sydell Levy Can you understand? Director of Youth Engagement Stessa Peers Israel Margoshes Am I awake? Daniel DeLevie Accompanists Katia Kravitz & Dror Perl * Ben Dorfman Arleen Meyers Am I prepared? Sidney Gilbert Vincent Peers Yai-lai lai lai