The Bibliofiles: Tony Diterlizzi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine #228

Where the good games are As I write this, the past weekend was the WINTER FANTASY ™ slots of the two LIVING DEATH adventures; all the judges sched- gaming convention. uled to run them later really wanted to play them first. That’s a It is over, and we’ve survived. WINTER FANTASY isn’t as hectic vote of confidence for you. or crowded as the GENCON® game fair, so we can relax a bit These judges really impressed me. For those of you who’ve more, meet more people, and have more fun. never played a LIVING CITY, LIVING JUNGLE™, or LIVING DEATH game, It was good meeting designers and editors from other game you don’t know what you’re missing. The judges who run these companies and discussing trends in the gaming industry, but it things are the closest thing to a professional corps of DMs that was also good sitting in the hotel bar (or better yet, Mader’s, I can imagine. Many judges have been doing this for years, and down the street) with old friends and colleagues and just talk- some go to gaming conventions solely for the purpose of run- ing shop. ning games. They really enjoy it, they’re really good, and they Conventions are business, but they are also fun. really know the rules. I came out of WINTER FANTASY with a higher respect for the Now the Network drops into GENCON gear. Tournaments are people who run these things. TSR’s new convention coordina- being readied and judges are signing up. -

The Spiderwick Chronicles

The Spiderwick Chronicles TeachingBooks Movie Transcript The Spiderwick Chronicles creators Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, interviewed in their studios in Amherst, MA on October 29, 2004. This is a transcript of the movie available on TeachingBooks.net. It is offered here to give you a quick assessment of the program topics, as well as to enable people with auditory disabilities access to the words. Because this is a transcript of an edited movie, it should not be used as an assessment of Mr. DiTerlizzi’s and Ms. Black’s writing. Many of the sentences found here were edited, and all editing decisions are the sole responsibility of TeachingBooks.net. Tony: Holly and I were doing a signing in New York City… Holly: Tony and I were signing in New York…. Tony: And we get this letter … Holly: The store clerk gave it to us and said that these kids had left it for us… Tony: They said, “We know you’re into fantasy. We know you like faeries and folklore and we have something we think might interest you and a story to go with it… Holly: And it was the letter that we put into The Spiderwick Chronicles… Tony: Their Great, Great Uncle, Arthur Spiderwick, had created this field guide to the faerie world… Holly: It was so cool, that we had to go ahead and contact them. What It’s All About Holly: The Spiderwick Chronicles are the story of Jared, Simon and Mallory Grace who move to their aunt’s. It’s a creepy old house and some creepy things start happening, and Jared finds Great, Great Uncle Arthur’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around Us. -

Test Your Faerie Knowledge

Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge It wasn’t all that long ago that faeries were regarded as the substance of the imagination. Boggarts, Elves, Dragons, Ogres . mankind scoffed at the idea that such fantastical beings could exist at all, much less inhabit the world around us. Of course, that was before Simon & Schuster published Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You. Now, we all know that faeries truly do exist. They’re out there, occasionally helping an unwary human, but more often causing mischief and playing tricks. How much do you know about the Invisible World? Have you studied up on your faerie facts? Put your faerie knowledge to the test and see how well you do in the following activities.When you’re finished, total up your score and see how much you really know. SCORING: 1-10 POINTS: Keep studying. In the meantime, you should probably steer clear of faeries of any kind. 11-20 POINTS: Pretty good! You might be able to trick a pixie, but you couldn’t fool a phooka. 21-30 POINTS: Wow, You’re almost ready to tangle with a troll! 31-39 POINTS: Impressive! You seem to know a lot about the faerie world —perhaps you’re a changeling... 40 POINTS: Arthur Spiderwick? Is that you? MY SCORE: REPRODUCIBLE SHEET Page 1 of 4 ILLUSTRATIONS © 2003, 2004, 2005 BY TONY DITERLIZZI Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge part 1 At any moment, you could stumble across a fantastical creature of the faerie world. -

Read Alike List

Read Alike List Juvenile/YA Fiction If you liked…. -The Fault in our Stars—If I Stay by Gayle Forman, Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell, Elsewhere by Gabrielle Zevin, Every Day by David Levithan, Zac and Mia by A.J. Betts, Paper Towns by John Green, Winger by Andrew Smith, And We Stay by Jenny Hubbard, An Abundance of Katherines by John Green, Wintergirls by Laurie Halse Anderson, Anna and the French Kiss by Stephanie Perkins, The Spectacular Now by Tim Tharp, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews, Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple, The Future of Us by Jay Asher & Carolyn Mackler, My Life After Now by Jessica Verdi, The Sky is Everywhere by Jandy Nelson, Twenty Boy Summer by Sarah Ockler, Love and Leftovers by Sarah Tregay, How to Save a Life by Sara Zarr, It’s Kind of a Funny Story by Ned Vizzini, The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, Looking for Alaska by John Green, Before I Fall by Lauren Oliver, Memoirs of a Teenage Amnesiac by Gabrielle Zevin, 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher, 13 Little Blue Envelopes by Maureen Johnson, Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour by Morgan Matson, The Beginning of Everything by Robyn Schneider, Me Before You by Jojo Moyes, Ask the Passengers by A.S. King, Love Letters to the Dead by Ava Dellaira -Divergent—Matched by Allyson Condie, Delirium by Lauren Oliver, Uglies by Scott Westerfeld, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins , The Giver by Lois Lowry, Unwind by Neal Shusterman, The Knife of Never Letting Go by Patrick Ness, Legend by Marie Lu, the Gone series by Michael Grant, Blood Red Road by Moira Young, The Maze Runner by James Dashner, The Selection by Kiera Cass, Article 5 by Kristen Simmons, Witch & Wizard by James Patterson, The Way We Fall by Megan Crewe, Shatter Me by Tahereh Mafi, Enclave by Ann Aguirre, Reboot by Amy Tintera, The Program by Suzanne Young, Taken by Erin Bowman, Birthmarked by Caragh M. -

Monster Manual

CREDITS MONSTER MANUAL DESIGN MONSTER MANUAL REVISION Skip Williams Rich Baker, Skip Williams MONSTER MANUAL D&D REVISION TEAM D&D DESIGN TEAM Rich Baker, Andy Collins, David Noonan, Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, Rich Redman, Skip Williams Skip Williams ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT ADDITIONAL DESIGN David Eckelberry, Jennifer Clarke Peter Adkison, Richard Baker, Jason Carl, Wilkes, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, William W. Connors, Sean K Reynolds Bill Slavicsek EDITORS PROOFREADER Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Jon Pickens Penny Williams EDITORIAL ASSITANCE Julia Martin, Jeff Quick, Rob Heinsoo, MANAGING EDITOR David Noonan, Penny Williams Kim Mohan MANAGING EDITOR D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kim Mohan Ed Stark CORE D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D Ed Stark Bill Slavicsek DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D ART DIRECTOR Bill Slavicsek Dawn Murin VISUAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR COVER ART Jon Schindehette Henry Higginbotham ART DIRECTOR INTERIOR ARTISTS Dawn Murin Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren D&D CONCEPTUAL ARTISTS Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Todd Lockwood, Sam Wood Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Scott Fischer, Rebecca Guay-Mitchell, Jeremy Jarvis, D&D LOGO DESIGN Paul Jaquays, Michael Kaluta, Dana Matt Adelsperger, Sherry Floyd Knutson, Todd Lockwood, David COVER ART Martin, Raven Mimura, Matthew Henry Higginbotham Mitchell, Monte Moore, Adam Rex, Wayne Reynolds, Richard Sardinha, INTERIOR ARTISTS Brian Snoddy, Mark Tedin, Anthony Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren Waters, Sam Wood Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Larry Elmore, GRAPHIC -

![[Free Pdf] Realms: the Roleplaying Art of Tony Diterlizzi Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6607/free-pdf-realms-the-roleplaying-art-of-tony-diterlizzi-online-1766607.webp)

[Free Pdf] Realms: the Roleplaying Art of Tony Diterlizzi Online

edham [Free pdf] Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi Online [edham.ebook] Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi Pdf Free Par Tony DiTerlizzi, Christopher Paolini, John Lind DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Publié le: 2015-06-16Sorti le: 2015-06-16Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 60.Mb Par Tony DiTerlizzi, Christopher Paolini, John Lind : Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles1 internautes sur 1 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Beau, créatif, vivant, émotionnelPar Docteur FoxLes créatures imaginées par Tony pour les mondes imaginaires que sont Planescape (Donjons et Dragons), Changelin, Magic et bien d'autres sont tout simplement belles à contempler et les retrouver dans ce magnifique ouvrage est un régal pour les yeux. Nous avons en outre de nombreuses informations sur le processus créatif de l'auteur, comme des photos de ses modèles.Un must pour tout amateur du travail de Tony.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Juste magnifiquePar Guillaume PulykDi Terlizzi a un monde bien à lui et il nous le fait partager via cet artbook assez complet et massif. Une très belle oeuvre Présentation de l'éditeurNew York Times bestselling creator Tony DiTerlizzi is known for his distinctive style depicting fantastical creatures, horrific monsters, and courageous heroes. His illustrations reshaped and defined the worlds of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, Planescape, and Magic: The Gathering in the imaginations of legions of devoted roleplaying gamers during the 1990s, before he transitioned to mainstream success with The Spiderwick Chronicles and The Search for WondLa. -

MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD of EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session

MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session The Mason City School District Board of Education met on June 12, 2008, in Regular Session in the Mason High School Harvard Room, 6100 South Mason-Montgomery Road, Mason, Ohio. I. OPENING CEREMONIES II. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL Connie Yingling, Board President, called the meeting to order at 5:35 PM. The following members were present: Connie Yingling, President Deborah Delp, Vice President Marianne Culbertson Kevin Wise, arrived at 5:40pm Jennifer Miller Also present were: Kevin Bright, Superintendent Richard Gardner, Treasurer Craig Ullery, Assistant Superintendent, Human Resources Bill Deters (left at 6:22 PM) Jennifer Miller (left at 6:35 PM & returned at 7:30 PM) III. EXECUTIVE SESSION Time: 5:35 PM It was moved by Mrs. Culbertson, seconded by Mrs. Delp, for the Board to enter into Executive Session for the purpose of Personnel. At the call of roll motion carried, Mrs. Culbertson, Yea; Mrs. Delp, Yea; Mrs. Miller, Yea; Mrs. Yingling, Yea; Mr. Wise, Absent. 4 Yeas. 1 Absent IV. RECONVENE TO REGULAR SESSION Time: 7:05 PM It was moved by Mr. Wise, seconded by Mrs. Culbertson, for the Board to Reconvene into Regular Session. At the call of roll motion carried, Mrs. Delp, Yea; Mrs. Miller, Absent; Mrs. Yingling, Yea; Mr. Wise, Yea; Mrs. Culbertson, Yea. 4 Yeas. 1 Absent. Also present for Regular Session: Deb Simpson Beth DeGroft Bob Bare Karen Bare Joe Delenzo Sharon Poe Dan Langen Steve Eckes 1 MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session V. -

Dragon Magazine #197

Issue #197 Vol. XVIII, No. 4 FEATURES September 1993 10 The Ecology of the Giant Scorpion Ruth Cooke Publisher Think invisibility will save you? Think again. James M. Ward 15 Think Bigin Miniature! James M. Ward Editor If a miniature could come to life, Ral Partha would be Roger E. Moore the company to make it. Associate editor Two Years of ORIGINS Awards The editors Dale A. Donovan 18 Is your game one of the best? Two years worth of awards will let you know. Fiction editor Barbara G. Young Perils & Postage Mark R. Kehl 24How to play an AD&D® campaign when each player Editorial assistant Wolfgang H. Baur lives in a different city. Art director By Mail or by Modem? Craig Schaefer Larry W. Smith 30 An AD&D game works just as well by BBS as by USPS (and maybe better). Production staff Tracey Zamagne The Dragons Bestiary Ed Greenwood 34 Its not a petting zoo: four new monsters from the Subscriptions Janet L. Winters FORGOTTEN REALMS® setting. The Known World Grimoire Bruce A. Heard U.S. advertising Cindy Rick 41 The world of Mystara is changing, but how? Turn to page 41 to find out. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Join the Electronic Warriors! James M. Ward Wendy Mottaz 67Whats in the works for computer gamers from the team of SSI and TSR. The MARVEL®-Phile Steven E. Schend 80 Its a dirty world in the streetsbut your heros there to clean it up. DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published tion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O. -

Elements of Writing a Paranormal Novel

Elements of Writing a Paranormal Novel by Steven Harper The most common question writers hear is, “Where do you get your ideas?” Some authors keep a pithy or smart-alecky answer ready, such as, “I belong to the Idea of the Month Club” or “I store a trunk of them in my attic.” More honest authors might answer, “I look at my bank ac- count. It’s amazing how many ideas a line of zeroes can generate.” A more useful answer is that you simply keep your eyes open. Fan- tasy author Mercedes Lackey once saw a small animal skitter across the road in front of her car. A split-second later, she realized her eyes were playing tricks—it was nothing but a piece of paper blown by the wind. Most people would think nothing of this and continue on their way, but Lackey is a writer. She played with the incident in her mind, asking herself why an animal might disguise itself as a piece of paper and what might happen if someone found such an animal. Eventually she wrote a story about it. The easiest way to find ideas is to play the “What If?” game. What if that piece of paper really were an animal? What if time ran backward when I turned my watch backward? What if a vampire needed to travel quickly from New York to Los Angeles? Could he send himself by FedEx? Another way to get novel-length ideas is to take two unrelated con- cepts and smoosh them together. If one of those elements is supernatu- ral, you have a paranormal book. -

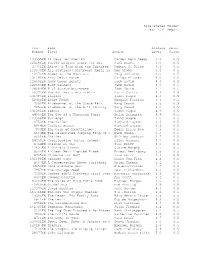

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 133355EN 14 Cows for America Carmen Agra Deedy 4.1 0.5 120186EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Carl Bowen 3.0 0.5 27701EN Akiak: A Tale from the Iditarod Robert J. Blake 3.3 0.5 129370EN All Stations! Distress! April 15 Don Brown 5.4 0.5 12472EN Amber on the Mountain Tony Johnston 3.0 0.5 131685EN Army Delta Force Carlos Alvarez 4.0 0.5 128662EN Army Green Berets Jack David 4.6 0.5 128683EN B-1B Lancers Jack David 4.9 0.5 128684EN B-52 Stratofortresses Jack David 4.7 0.5 20672EN The Bat Boy & His Violin Gavin Curtis 4.1 0.5 131390EN Beagles Tammy Gagne 4.6 0.5 12469EN Beast Feast Douglas Florian 4.4 0.5 7952EN Bluebonnet at the State Fair Mary Casad 3.3 0.5 7953EN Bluebonnet of the Hill Country Mary Casad 4.0 0.5 131391EN Boxers Tammy Gagne 4.9 0.5 44065EN The Boy of a Thousand Faces Brian Selznick 4.8 0.5 123368EN Bulldogs Tammy Gagne 4.5 0.5 8753EN The Caller Richard Laymon 3.3 0.5 8804EN Cardiac Arrest Richard Laymon 3.2 0.5 7904EN The Cask of Amontillado Edgar Allan Poe 7.3 0.5 8604EN The Celebrated Jumping Frog of C Mark Twain 6.9 0.5 8605EN Charles Shirley Jackson 3.7 0.5 54039EN Cheerleading (After School) Ellen Rusconi 5.0 0.5 8754EN Chicken by Che Tana Reiff 3.0 0.5 12697EN A Child's Alaska Claire Murphy 5.7 0.5 8606EN A Clean Well-Lighted Place Ernest Hemingway 3.3 0.5 8705EN Climbing the Wall Tana Reiff 2.9 0.5 131688EN Concept Cars Denny Von Finn 4.1 0.5 8607EN A Conversation About Christmas Dylan Thomas 5.2 0.5 34653EN Cook-a-doodle-doo! Stevens/Crummel 2.7 0.5 7957EN The Courage Seed Jean Richardson 4.6 0.5 7959EN Cowboy Bob's Critters Visit Texa Marjorie vonRosenb 3.5 0.5 8409EN Cowboy Country Ann Scott 4.4 0.5 85025EN The Curse of King Tut's Tomb Michael Burgan 4.5 0.5 12468EN Dandelions Eve Bunting 3.5 0.5 119370EN David Beckham Jeff Savage 4.6 0.5 115738EN The Day the Stones Walked T.A. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

13238 Spiderwick Chronicles Tg.Pdf

A Teacher ’s Guide to ABOUT THE BOOKS When Jared, Simon, and Mallory Grace moved into their great-great-uncle Arthur Spiderwick’s estate, they had no idea what awaited them. But once Jared finds Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You, he discovers a world of trolls, goblins, and sprites. And after meeting their house brownie, Thimbletack, Jared learns that his family is in danger from the fantastical world around them. Then in the Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles series, The Spiderwick Chronicles leave the old-fashioned charm of New England behind and head south to embark on a whole new journey with Nick and Laurie as they continue the fight against fiendish fairies in the hot Florida sun. ABOUT THE CREATORS Tony DiTerlizzi is a New York Times bestselling author and illustrator who has been creating books with Simon & Schuster for more than a decade. From his fanciful picture books like Jimmy Zangwow’s Out-of-this-World Moon Pie Adventure , Adventures of Meno (with his wife, Angela), and The Spider & The Fly (a Caldecott Honor book), to chapter books like Kenny and The Dragon and The Search for WondLa , Tony always imbues his stories with a rich imagination. You can visit him at DiTerlizzi.com. Holly Black spent her early years in a decaying Victorian mansion, where her mother fed her a steady diet of ghost stories and books about faeries. However, Holly is now the author of bestselling contemporary fantasy books for kids and teens. In addition to The Spiderwick Chronicles (with Tony DiTerlizzi), some of her titles include the Modern Faerie Tale series, the Curse Workers series, and her ghostly middle grade novel, Doll Bones, which received six starred reviews and a Newbery Honor.