Elements of Writing a Paranormal Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine #228

Where the good games are As I write this, the past weekend was the WINTER FANTASY ™ slots of the two LIVING DEATH adventures; all the judges sched- gaming convention. uled to run them later really wanted to play them first. That’s a It is over, and we’ve survived. WINTER FANTASY isn’t as hectic vote of confidence for you. or crowded as the GENCON® game fair, so we can relax a bit These judges really impressed me. For those of you who’ve more, meet more people, and have more fun. never played a LIVING CITY, LIVING JUNGLE™, or LIVING DEATH game, It was good meeting designers and editors from other game you don’t know what you’re missing. The judges who run these companies and discussing trends in the gaming industry, but it things are the closest thing to a professional corps of DMs that was also good sitting in the hotel bar (or better yet, Mader’s, I can imagine. Many judges have been doing this for years, and down the street) with old friends and colleagues and just talk- some go to gaming conventions solely for the purpose of run- ing shop. ning games. They really enjoy it, they’re really good, and they Conventions are business, but they are also fun. really know the rules. I came out of WINTER FANTASY with a higher respect for the Now the Network drops into GENCON gear. Tournaments are people who run these things. TSR’s new convention coordina- being readied and judges are signing up. -

The Spiderwick Chronicles

The Spiderwick Chronicles TeachingBooks Movie Transcript The Spiderwick Chronicles creators Holly Black and Tony DiTerlizzi, interviewed in their studios in Amherst, MA on October 29, 2004. This is a transcript of the movie available on TeachingBooks.net. It is offered here to give you a quick assessment of the program topics, as well as to enable people with auditory disabilities access to the words. Because this is a transcript of an edited movie, it should not be used as an assessment of Mr. DiTerlizzi’s and Ms. Black’s writing. Many of the sentences found here were edited, and all editing decisions are the sole responsibility of TeachingBooks.net. Tony: Holly and I were doing a signing in New York City… Holly: Tony and I were signing in New York…. Tony: And we get this letter … Holly: The store clerk gave it to us and said that these kids had left it for us… Tony: They said, “We know you’re into fantasy. We know you like faeries and folklore and we have something we think might interest you and a story to go with it… Holly: And it was the letter that we put into The Spiderwick Chronicles… Tony: Their Great, Great Uncle, Arthur Spiderwick, had created this field guide to the faerie world… Holly: It was so cool, that we had to go ahead and contact them. What It’s All About Holly: The Spiderwick Chronicles are the story of Jared, Simon and Mallory Grace who move to their aunt’s. It’s a creepy old house and some creepy things start happening, and Jared finds Great, Great Uncle Arthur’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around Us. -

Test Your Faerie Knowledge

Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge It wasn’t all that long ago that faeries were regarded as the substance of the imagination. Boggarts, Elves, Dragons, Ogres . mankind scoffed at the idea that such fantastical beings could exist at all, much less inhabit the world around us. Of course, that was before Simon & Schuster published Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You. Now, we all know that faeries truly do exist. They’re out there, occasionally helping an unwary human, but more often causing mischief and playing tricks. How much do you know about the Invisible World? Have you studied up on your faerie facts? Put your faerie knowledge to the test and see how well you do in the following activities.When you’re finished, total up your score and see how much you really know. SCORING: 1-10 POINTS: Keep studying. In the meantime, you should probably steer clear of faeries of any kind. 11-20 POINTS: Pretty good! You might be able to trick a pixie, but you couldn’t fool a phooka. 21-30 POINTS: Wow, You’re almost ready to tangle with a troll! 31-39 POINTS: Impressive! You seem to know a lot about the faerie world —perhaps you’re a changeling... 40 POINTS: Arthur Spiderwick? Is that you? MY SCORE: REPRODUCIBLE SHEET Page 1 of 4 ILLUSTRATIONS © 2003, 2004, 2005 BY TONY DITERLIZZI Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge part 1 At any moment, you could stumble across a fantastical creature of the faerie world. -

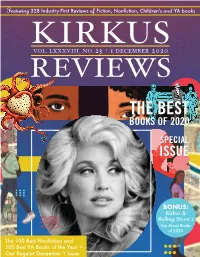

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

A Plane Shift: Ixalan Adventure for Dungeons & Dragons

X MARKS THE SPOT A prison escape for an unlikely group of heroes turns into a race for an ancient relic sought by the Legion of Dusk. Can you brave the unknown and capture the treasure before the enemy does? This D&D adventure is set on the plane of Ixalan, and uses 4th-level pregenerated characters. A Plane Shift: Ixalan Adventure for Dungeons & Dragons Credits Designers: Kat Kruger, Chris Tulach MAGIC: THE GATHERING, DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, Magic, D&D, Ixalan, Player’s Plane Shift: Ixalan Design: James Wyatt Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, WUBRG, all other Wizards of Editor: Scott Fitzgerald Gray the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Graphic Designer: Emi Tanji Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are Cover Illustrator: Cliff Childs property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws Interior Illustrators: Tommy Arnold, John Avon, Naomi Baker, of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material Milivoj Ceran,́ Zezhou Chen, Daarken, Dimitar, Emrah Elmasil, or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. Florian de Gesincourt, Ryan Alexander Lee, Slawomir Maniak, Aaron Miller, Victor Adame Minguez, Dan Scott, John Stanko, ©2017 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufac- YW Tang, Ben Wooten, Kieran Yanner tured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Has- Cartographer: Jared Blando bro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. -

Read Alike List

Read Alike List Juvenile/YA Fiction If you liked…. -The Fault in our Stars—If I Stay by Gayle Forman, Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell, Elsewhere by Gabrielle Zevin, Every Day by David Levithan, Zac and Mia by A.J. Betts, Paper Towns by John Green, Winger by Andrew Smith, And We Stay by Jenny Hubbard, An Abundance of Katherines by John Green, Wintergirls by Laurie Halse Anderson, Anna and the French Kiss by Stephanie Perkins, The Spectacular Now by Tim Tharp, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews, Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple, The Future of Us by Jay Asher & Carolyn Mackler, My Life After Now by Jessica Verdi, The Sky is Everywhere by Jandy Nelson, Twenty Boy Summer by Sarah Ockler, Love and Leftovers by Sarah Tregay, How to Save a Life by Sara Zarr, It’s Kind of a Funny Story by Ned Vizzini, The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, Looking for Alaska by John Green, Before I Fall by Lauren Oliver, Memoirs of a Teenage Amnesiac by Gabrielle Zevin, 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher, 13 Little Blue Envelopes by Maureen Johnson, Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour by Morgan Matson, The Beginning of Everything by Robyn Schneider, Me Before You by Jojo Moyes, Ask the Passengers by A.S. King, Love Letters to the Dead by Ava Dellaira -Divergent—Matched by Allyson Condie, Delirium by Lauren Oliver, Uglies by Scott Westerfeld, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins , The Giver by Lois Lowry, Unwind by Neal Shusterman, The Knife of Never Letting Go by Patrick Ness, Legend by Marie Lu, the Gone series by Michael Grant, Blood Red Road by Moira Young, The Maze Runner by James Dashner, The Selection by Kiera Cass, Article 5 by Kristen Simmons, Witch & Wizard by James Patterson, The Way We Fall by Megan Crewe, Shatter Me by Tahereh Mafi, Enclave by Ann Aguirre, Reboot by Amy Tintera, The Program by Suzanne Young, Taken by Erin Bowman, Birthmarked by Caragh M. -

Monster Manual

CREDITS MONSTER MANUAL DESIGN MONSTER MANUAL REVISION Skip Williams Rich Baker, Skip Williams MONSTER MANUAL D&D REVISION TEAM D&D DESIGN TEAM Rich Baker, Andy Collins, David Noonan, Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, Rich Redman, Skip Williams Skip Williams ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT ADDITIONAL DESIGN David Eckelberry, Jennifer Clarke Peter Adkison, Richard Baker, Jason Carl, Wilkes, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, William W. Connors, Sean K Reynolds Bill Slavicsek EDITORS PROOFREADER Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Jon Pickens Penny Williams EDITORIAL ASSITANCE Julia Martin, Jeff Quick, Rob Heinsoo, MANAGING EDITOR David Noonan, Penny Williams Kim Mohan MANAGING EDITOR D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kim Mohan Ed Stark CORE D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D Ed Stark Bill Slavicsek DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D ART DIRECTOR Bill Slavicsek Dawn Murin VISUAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR COVER ART Jon Schindehette Henry Higginbotham ART DIRECTOR INTERIOR ARTISTS Dawn Murin Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren D&D CONCEPTUAL ARTISTS Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Todd Lockwood, Sam Wood Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Scott Fischer, Rebecca Guay-Mitchell, Jeremy Jarvis, D&D LOGO DESIGN Paul Jaquays, Michael Kaluta, Dana Matt Adelsperger, Sherry Floyd Knutson, Todd Lockwood, David COVER ART Martin, Raven Mimura, Matthew Henry Higginbotham Mitchell, Monte Moore, Adam Rex, Wayne Reynolds, Richard Sardinha, INTERIOR ARTISTS Brian Snoddy, Mark Tedin, Anthony Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren Waters, Sam Wood Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Larry Elmore, GRAPHIC -

![[Free Pdf] Realms: the Roleplaying Art of Tony Diterlizzi Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6607/free-pdf-realms-the-roleplaying-art-of-tony-diterlizzi-online-1766607.webp)

[Free Pdf] Realms: the Roleplaying Art of Tony Diterlizzi Online

edham [Free pdf] Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi Online [edham.ebook] Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi Pdf Free Par Tony DiTerlizzi, Christopher Paolini, John Lind DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Publié le: 2015-06-16Sorti le: 2015-06-16Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 60.Mb Par Tony DiTerlizzi, Christopher Paolini, John Lind : Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Realms: The Roleplaying Art of Tony DiTerlizzi: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles1 internautes sur 1 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Beau, créatif, vivant, émotionnelPar Docteur FoxLes créatures imaginées par Tony pour les mondes imaginaires que sont Planescape (Donjons et Dragons), Changelin, Magic et bien d'autres sont tout simplement belles à contempler et les retrouver dans ce magnifique ouvrage est un régal pour les yeux. Nous avons en outre de nombreuses informations sur le processus créatif de l'auteur, comme des photos de ses modèles.Un must pour tout amateur du travail de Tony.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Juste magnifiquePar Guillaume PulykDi Terlizzi a un monde bien à lui et il nous le fait partager via cet artbook assez complet et massif. Une très belle oeuvre Présentation de l'éditeurNew York Times bestselling creator Tony DiTerlizzi is known for his distinctive style depicting fantastical creatures, horrific monsters, and courageous heroes. His illustrations reshaped and defined the worlds of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, Planescape, and Magic: The Gathering in the imaginations of legions of devoted roleplaying gamers during the 1990s, before he transitioned to mainstream success with The Spiderwick Chronicles and The Search for WondLa. -

Classic Play the Book of the Planes Gareth Hanrahan

Classic Play The Book of the Planes Gareth Hanrahan Contents Credits Introduction 2 Planar Traits 4 Travelling the Planes 26 Editor & Developer Fellow Travellers 36 Richard Neale Magic of the Planes 50 The Ethereal Plane 61 The Astral Plane 68 Studio Manager The Plane of Shadow 82 Ian Barstow The Plane of Dreams 89 The Elemental Plane of Earth 93 The Elemental Plane of Air 101 Cover Art The Elemental Plane of Fire 108 The Elemental Plane of Water 115 Vincent Hie The Plane of Positive Energy 121 The Plane of Negative Energy 127 The Vault of Stars 132 Interior Illustrations Tarassein 137 Joey Stone, Danilo Moreti, David Esbri Mâl 142 Infernum 148 Molinas, Tony Parker, Phil Renne, Carlos Chasm 153 Henry, Marcio Fiorito Jesus Barony, Gillian The Halls of Order 159 Pearce, Reynato Guides & Nathan Webb The Afterworld 164 The Firmament 171 The Questing Grounds 177 Production Manager Nexus Planes 183 The Grand Orrery of All Reflected Heavens 184 Alexander Fennell The Wandering Inn of the Glorious Toad 197 Dunmorgause Castle 207 Lesser Planes 216 Proofreading Building the Cosmos 222 Fred Herman and Mark Quinnell Planecrafting 234 Designer’s Notes 247 Random Plane Table 248 Index 250 Open Game Content & Copyright Information Classic Play - The Book of the Planes©2004 Mongoose Publishing. All rights reserved. Reproduction of non-Open Game Content of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Classic Play - The Book of the Planes is presented under the Open Game and D20 Licences. See page 256 for the text of the Open Game Licence. -

Languages of Harqual

LANGUAGES For Lands of Harqual WORLD LANGUAGES Language Typical Speaker/Region Alphabet Abyssal Demons, chaotic evil outsiders Infernal Aethercommon Denizens of Wildspace and the Flow Elven Anarchic Chaotic outsiders Infernal Aquan Water-based creatures, the Tullelands Elven Auran Air-based creatures Draconic Axiomatic Lawful outsiders Celestial Celestial Good outsiders Celestial Draconic Kobolds, troglodytes, lizardfolk, dragons, dracovarans Draconic Druidic * Druids, clerics of Mirella, dracovarans Druidic Dwarven Dwarves, grendles, muls, watchers, wendigos Dwarven Elven Elves, aellar, ee’aar, houri, the luminous, the rmoahali Elven Giant Giants, jätten, jovians, ogres, wind lords Giant Gith (high) * Githyanki, githzerai, Pirates of Gith, some goblinoids High Gith Gnoll Gnolls, flinds, half-gnolls, tri-clops Goblin Gnome Rockwood gnomes, morlocks, star gnomes, kitts Gnome Goblin Baklath, bhuka, bugbears, krugs, hobgoblins, mountain orcs Goblin Hadozee Hadozee n/a Halfling Halflings, kitts Elven Ignan Fire-base creatures Draconic Infernal Devils, lawful evil outsiders Infernal Kitt Kitts, some halflings Rakasta Kreen * Thri-kreen Druidic Maenad * Maenads Maenad Orc Orcs, half-orcs, jovians, mountain orcs, tri-clops Goblin Rakasta Rakasta, kitts, terrigs, good-aligned tabaxi Rakasta Sign Language Many humanoid cultures, any deaf person n/a Terran Earth ogres, xorns and other earth-based creatures Dwarven Speakshadow * Language that originates from the Shadowstar Sea Draconic Xeph * Xephs Xeph Yuan-Ti Yuan-ti, yuan-ti anathemas, ophidians, -

MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD of EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session

MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session The Mason City School District Board of Education met on June 12, 2008, in Regular Session in the Mason High School Harvard Room, 6100 South Mason-Montgomery Road, Mason, Ohio. I. OPENING CEREMONIES II. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL Connie Yingling, Board President, called the meeting to order at 5:35 PM. The following members were present: Connie Yingling, President Deborah Delp, Vice President Marianne Culbertson Kevin Wise, arrived at 5:40pm Jennifer Miller Also present were: Kevin Bright, Superintendent Richard Gardner, Treasurer Craig Ullery, Assistant Superintendent, Human Resources Bill Deters (left at 6:22 PM) Jennifer Miller (left at 6:35 PM & returned at 7:30 PM) III. EXECUTIVE SESSION Time: 5:35 PM It was moved by Mrs. Culbertson, seconded by Mrs. Delp, for the Board to enter into Executive Session for the purpose of Personnel. At the call of roll motion carried, Mrs. Culbertson, Yea; Mrs. Delp, Yea; Mrs. Miller, Yea; Mrs. Yingling, Yea; Mr. Wise, Absent. 4 Yeas. 1 Absent IV. RECONVENE TO REGULAR SESSION Time: 7:05 PM It was moved by Mr. Wise, seconded by Mrs. Culbertson, for the Board to Reconvene into Regular Session. At the call of roll motion carried, Mrs. Delp, Yea; Mrs. Miller, Absent; Mrs. Yingling, Yea; Mr. Wise, Yea; Mrs. Culbertson, Yea. 4 Yeas. 1 Absent. Also present for Regular Session: Deb Simpson Beth DeGroft Bob Bare Karen Bare Joe Delenzo Sharon Poe Dan Langen Steve Eckes 1 MASON CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION June 12, 2008, Regular Session V. -

Dragon Magazine #197

Issue #197 Vol. XVIII, No. 4 FEATURES September 1993 10 The Ecology of the Giant Scorpion Ruth Cooke Publisher Think invisibility will save you? Think again. James M. Ward 15 Think Bigin Miniature! James M. Ward Editor If a miniature could come to life, Ral Partha would be Roger E. Moore the company to make it. Associate editor Two Years of ORIGINS Awards The editors Dale A. Donovan 18 Is your game one of the best? Two years worth of awards will let you know. Fiction editor Barbara G. Young Perils & Postage Mark R. Kehl 24How to play an AD&D® campaign when each player Editorial assistant Wolfgang H. Baur lives in a different city. Art director By Mail or by Modem? Craig Schaefer Larry W. Smith 30 An AD&D game works just as well by BBS as by USPS (and maybe better). Production staff Tracey Zamagne The Dragons Bestiary Ed Greenwood 34 Its not a petting zoo: four new monsters from the Subscriptions Janet L. Winters FORGOTTEN REALMS® setting. The Known World Grimoire Bruce A. Heard U.S. advertising Cindy Rick 41 The world of Mystara is changing, but how? Turn to page 41 to find out. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Join the Electronic Warriors! James M. Ward Wendy Mottaz 67Whats in the works for computer gamers from the team of SSI and TSR. The MARVEL®-Phile Steven E. Schend 80 Its a dirty world in the streetsbut your heros there to clean it up. DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published tion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O.