Evolution of the Werewolf Archetype from Ovid to J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberpunking a Library

Cyberpunking a Library Collection assessment and collection Leanna Jantzi, Neil MacDonald, Samantha Sinanan LIBR 580 Instructor: Simon Neame April 8, 2010 “A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void.” – Neuromancer, William Gibson 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of Subject ....................................................................................................................................... 3 History of Cyberpunk .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Themes and Common Motifs....................................................................................................................................... 3 Key subject headings and Call number range ....................................................................................................... 4 Description of Library and Community ..................................................................................................... -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Werewolf Trivia Quiz

WEREWOLF TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> According to legend, which of these items do werewolves hate? a. Sage b. Basil c. Garlic d. Salt 2> What is the term used to describe when a person changes into a wolf? a. Lycanthropy b. Hycanthropy c. Alluranthropy d. Cynanthropy 3> The "Beast of Gevaudan" incident occurred in which nation? a. England b. Germany c. France d. America 4> What kind of bullet will kill a werewolf? a. Silver b. Copper c. Pewter d. Gold 5> What is the name of the Norse wolf god? a. Hei b. Odin c. Loki d. Fenrir 6> Which of these plants will repel a werewolf? a. Mistletoe b. Poinsettia c. Lily d. Orchid 7> In which of these movies did Michael J. Fox play a werewolf? a. Cursed b. Teen Wolf c. Bad Moon d. An American Werewolf in London 8> Which artist recorded the 1978 hit, "Werewolves in London"? a. Elvis Costello b. Warren Zevon c. Neil Diamond d. David Bowie 9> If chased by a werewolf, which tree would be the best to climb? a. Olive b. Popular c. Maple d. Ash 10> Released in 1941, who plays Lawrence Talbot in the werewolf cult classic "The Wolf Man"? a. Lon Chaney b. Bela Lugosi c. Ralph Bellamy d. Claude Rains 11> What kind of crop can protect you from a werewolf? a. Oats b. Wheat c. Rye d. Corn 12> What is the setting for the classic werewolf film "Dog Soldiers"? a. South Africa b. Peru c. Scotland d. Germany 13> Which of the following elements will provide an excellent defense against werewolves? a. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Seana Gorlick Local 706 Makeup Artist Seanabrehgorlick.Com (661) 233-2162

Seana Gorlick Local 706 Makeup Artist Seanabrehgorlick.com (661) 233-2162 Training: MKC Beauty Academy Masters Makeup Program Airbrushing Clients: Tyler Posey Natalie Martinez Shelley Hennig Dylan Sprayberry Dylan O’Brien Holland Roden Tyler Hoechlin Paul Sorvino Charlie Carver Colton Haynes Daniel Sharman Paul Ben-Victor Kendrick Sampson Chris Zylka Rachel Boston Noah Bean JB Smoove Josie Davis Daniella Bobadilla Thomas F. Wilson Max Carver Ayla Kell Tricia O’Kelley Marin Hinkle James Cromwell Joanna Cassidy Harley Quinn Smith Lily Rose Depp Austin Butler Productions: ABC Television Fall Premiere Event 2010 “The Time” Documentary All American Rejects Music Video; The Beekeeper’s Daughter Black Marigolds; Independent Film No Business Like; Webisode Sunday Guests; Short Film Stalked At 17; Lifetime Feature Film Here For Now; Independent Film The Big Day; Independent Film Another Christmas, Independent Film Good Day LA; Talk Show (Tyler Posey) One Night; Independent Film Nighttime; Short Film Coming Home; Short Film ALLOY Teen Wolf Promotional Video Burton Snowboards Spring/Summer '12 and Fall/Winter '12 Ad Campaign Spy Optic RX 2013 Catalog Carriers; Lifetime Feature Film I Heard; Web Series High School Crush; Lifetime Feature Film Deceit; Lifetime Feature Film RVC Web Series; Created by TJ Miller Missing; Lifetime Feature Film The Cheating Pact; Lifetime Feature Film The Perfect Boyfriend; Lifetime Feature Film Night Vet; Short Film Blood Relatives; TV Series MTV Online Teen Wolf After Show Variety Magazine Cover (Tyler Posey) Zach Stone Is Gonna Be Famous; Cast Interviews Comic Con 2013 for Teen Wolf Cast Burton Snowboards Spring/Summer ’14 Ad Campaign Teen Wolf; TV Series (Season 3B and 4) TV Guide Cover (Tyler Posey) The Today Show; Teen Wolf (Tyler Posey and Tyler Hoechlin) Comic Con 2014; Teen Wolf Cast Teen Choice Awards 2014 Yoga Hosers; Motion Picture Tabloid; TV Series. -

Cineyouth 2021 Film Selection

The 2021 CineYouth Programs and Film Selection The Cinemas of Chicago (Opening Night) Our city has proven once again to be fertile ground for filmmakers to find sources of creative self-expression, and these shorts are a mere sample of what the future holds for Chicago cinema. RAICES Andres Aurelio | Chicago/Mexico | Age 21 Reflecting on his passion for gardening, a man finds the source of this infatuation in Mexico. Now living in the United States, he seeks to plant his pride from the Mexico family garden into his new one. Love Stories Elizabeth Myles | Chicago | Age 21 Unique love stories are touchingly explored from multiple perspectives through experimental animation of archival personal photographs, investigating what it means to love in this world. Miniature Vacation Samantha Ocampo | Chicago| Age 16 In this visual adaptation of her own poem, filmmaker Samantha Ocampo reveals the little local things she appreciates in her life that help her escape the day-to-day banality. The Wolf Comes at Night Nathan Marquez | Chicago | Age 22 An ominous presence comes from out of the darkness, terrorizing a cattle farm where a frightened grandfather and his grandchildren are trying to protect themselves and the farm. Face Me Ty Yamamoto | Chicago | Age 21 This provocative look into Hollywood's history examines the use of yellowface and its continued impact on the Asian-American community by projecting media onto the faces of the younger generation. De Sol a Sol Shira Baron | Chicago | Age 21 On warm summer days you can find Abraham and Ricardo selling ice cream along the Chicago lakefront, but a new perspective offers a glimpse into the often harrowing experiences of ice cream men. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Vampires Now and Then

Hugvisindasvið Vampires Now and Then From origins to Twilight and True Blood Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Daði Halldórsson Maí 20 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska Vampires Now and Then From origins to Twilight and True Blood Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Daði Halldórsson Kt.: 250486-3599 Leiðbeinandi: Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir Maí 2010 This essay follows the vampires from their origins to their modern selves and their extreme popularity throughout the years. The essay raises the question of why vampires are so popular and what it is that draws us to them. It will explore the beginning of the vampire lore, how they were originally just cautionary tales told by the government to the villagers to scare them into a behavior that was acceptable. In the first chapter the mythology surrounding the early vampire lore will be discussed and before moving on in the second chapter to the cult that has formed around the mythological and literary identities of these creatures. The essay finishes off with a discussion on the most recent popular vampire related films Twilight and New Moon and TV-series True Blood and their male vampire heroes Edward Cullen and Bill Compton. The essay relies heavily on The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and other Monsters written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley as well as The Dead Travel Fast: Stalking Vampires from Nosferatu to Count Chocula written by Eric Nuzum as well as the films Twilight directed by Catherine Hardwicke and New Moon directed by Chris Weitz and TV-series True Blood. Eric Nuzum's research on the popularity of vampires inspired the writing of this essay. -

Constructing the Witch in Contemporary American Popular Culture

"SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES": CONSTRUCTING THE WITCH IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Catherine Armetta Shufelt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor Dr. Andrew M. Schocket Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Esther Clinton © 2007 Catherine A. Shufelt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor What is a Witch? Traditional mainstream media images of Witches tell us they are evil “devil worshipping baby killers,” green-skinned hags who fly on brooms, or flaky tree huggers who dance naked in the woods. A variety of mainstream media has worked to support these notions as well as develop new ones. Contemporary American popular culture shows us images of Witches on television shows and in films vanquishing demons, traveling back and forth in time and from one reality to another, speaking with dead relatives, and attending private schools, among other things. None of these mainstream images acknowledge the very real beliefs and traditions of modern Witches and Pagans, or speak to the depth and variety of social, cultural, political, and environmental work being undertaken by Pagan and Wiccan groups and individuals around the world. Utilizing social construction theory, this study examines the “historical process” of the construction of stereotypes surrounding Witches in mainstream American society as well as how groups and individuals who call themselves Pagan and/or Wiccan have utilized the only media technology available to them, the internet, to resist and re- construct these images in order to present more positive images of themselves as well as build community between and among Pagans and nonPagans. -

Recommended Books from the Teen Collection

Recommended Books from the Teen Collection Action, Adventure, and Survival Crime, Espionage, Escape, and Heists TEEN BARDUGO Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo (790L, series, grades 7+) TEEN CARRIGER Etiquette & Espionage by Gail Carriger (780L, series, grades 6+) TEEN CARTER Heist Society by Ally Carter (800L, series, grades 7+) TEEN CARTER I’d Tell You I Love You, But Then I’d Have to Kill You by Ally Carter (1000L, series, grades 6+) TEEN DUCIE The Rig by Joe Ducie (grades 6+) TEEN EVANS Michael Vey: the Prisoner of Cell 25 by Richard Paul Evans (500L, grades 6+) TEEN HOROWITZ Stormbreaker by Anthony Horowitz (670L, series, grades 6+) TEEN MAETANI Ink and Ashes by Valynne E. Maetani (740L, grades 7+) TEEN MCKENZIE In a Split Second by Sophie McKenzie (670L, grades 8+) TEEN SMITH Independence Hall by Roland Smith (660L, series, grades 5+) Survival TEEN BICK Ashes by Ilsa Bick (730L, series, grades 7+) TEEN CALAME Dan Versus Nature by Don Calame (660L, grades 8+) TEEN DELAPEÑA The Living by Matt De La Peña (700L, series, grades 9+) TEEN FULLER Our Endless Numbered Days by Claire Fuller (980L, grades 9+) TEEN GRIFFIN Adrift by Paul Griffin (580L, grades 9+) TEEN HAINES Girl in the Arena: a Novel Containing Intense Prolonged Sequences of Disaster and Peril by Lise Haines (grades 9+) TEEN HIRSCH Black River Falls by Jeff Hirsch (700L, grades 7+) TEEN HURWITZ The Rains by Gregg Andrew Hurwitz (770L, grades 7+) TEEN KEPHART This is the Story of You by Beth Kephart (850L, grades 7+) TEEN LEVEZ The Island by Olivia Levez (grades 7+) TEEN MALLORY -

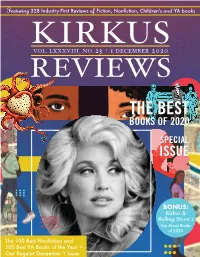

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb.