Andrew Blaikie IRSS 38 (2013) 11 IMAGE and INVENTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

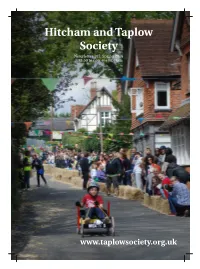

Hitcham and Taplow Society Newsletter Spring 2016

Hitcham and Taplow Society Newsletter 105: Spring 2016 £3.50 to nonmembers www.taplowsociety.org.uk Hitcham and Taplow Society Formed in 1959 to protect Hitcham, Taplow and the surrounding countryside from being spoilt by bad development and neglect. President: Eva Lipman Vice Presidents: Tony Hickman, Fred Russell, Professor Bernard Trevallion OBE Chairman: Karl Lawrence Treasurer: Myra Drinkwater Secretary: Roger Worthington Committee: Heather Fenn, Charlie Greeves, Robert Harrap, Zoe Hatch, Alastair Hill, Barrie Peroni, Nigel Smales, Louise Symons, Miv WaylandSmith Website Adviser & Newsletter Production: Andrew Findlay Contact Address: HTS, Littlemere, River Road, Taplow, SL6 0BB [email protected] 07787 556309 Cover picture: Sarah & Tony Meats' grandson Herbie during the Race to the Church (Nigel Smales) Editorial Change: the only constant? There's certainly a lot This Newsletter is a bumper edition to feature of it about. Down by the Thames, the change is a few milestones: two cherished memories of physical (see Page 7). Up in the Village, it is notsolong ago were revived recently to mark personal (see Pages 17, 18 & 19). Some changes the Queen’s 90th birthday (see Pages 9, 14 & 15) stand the tests of time (see Pages 1013 & 16). and Cedar Chase celebrates its Golden Jubilee Will the same be said for potential changes in (see Pages 1013). Buffins and Wellbank are of the pipeline (see Pages 4, 5 & 6) which claim similar vintage; perhaps they can be persuaded roots in evidenceled policymaking while to pen pieces for future editions. We are whiffing of policyled evidencemaking? delighted to welcome Amber, our youngestever The Society faces three changes. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

Newspaper Index H

Watt Library, Greenock Newspaper Index This index covers stories that have appeared in newspapers in the Greenock, Gourock and Port Glasgow area from the start of the nineteenth century. It is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Subject Entry Newspaper Date Page H.D. Lee Ltd., Greenock H D Lee Ltd, clothing manufacturers, opening another factory on the Larkfield Estate Greenock Telegraph 22/01/1972 1 creating 500 new jobs H.D. Lee Ltd., Greenock Opening of clothing factory of H D Lee, Inc. Kansas on Larkfield Industrial Estate Greenock Telegraph 13/06/1970 7 Hairdressers' Society General meeting to discuss proposal to dissolve society. Greenock Advertiser 09/08/1831 3 Hairdressers' Society Dissolved 20 January, payment to all members and widows of members. Greenock Advertiser 19/02/1835 3 Haltonridge Farm, Kilmacolm Haltonridge Farm to be let Greenock Advertiser 11/05/1812 1 Hamburg Article on Hamburg Amerika and Norddeutscher Lloyd Lines which not only used the Greenock Telegraph 28/07/1983 16 Amerika/Norddeutscher Lloyd harbours but had ships built in Greenock. Lines Hamburg-Amerika Line Article on Hamburg-Amerika and Norddeutscher Lloyds line which used local harbours Greenock Telegraph 28/07/1983 16 Hamilton Free Church, Port Brief history of Hamilton Free Church and description Greenock Telegraph 09/06/1894 2 Glasgow Hamilton Free Church, Port Centenary of Hamilton -

1 TB, Glasgow and the Mass Radiography Campaign in The

1 TB, Glasgow and the Mass Radiography Campaign in the Nineteen Fifties: A Democratic Health Service in Action. A paper prepared for Scottish Health History: International Contexts, Contemporary Perspectives Colloquium hosted by the Centre for the History of Medicine University of Glasgow 20 th June 2003 by Ian Levitt University of Central Lancashire On February 21 1956, James Stuart, the Scottish Secretary of State, announced plans for what he termed ‘the most ambitious campaign against pulmonary tuberculosis 1 yet attempted’ in Scotland. It was to last two years, starting in early 1957. The emphasis of the campaign was ‘on the detection of the infectious person, his treatment, to follow those who had been in contact’ with the infectious person and ‘to find and bring under control the maximum number of undetected cases of tuberculosis, and thus to prevent the spread of infection and substantially reduce the incidence of new diseases in future.’ 2 Its principal weapon was the x-ray survey, based on miniature mass radiography. Stuart was undoubtedly a concerned political administrator. In announcing the campaign he stated that, unlike England, notification of new cases of respiratory TB had increased since the war, especially in Glasgow (the latter from 139 to 200 per 100,000 population). Although the death rate had declined (in Glasgow from 86 to 34 per 100,000 population), it was still more than double the figure further south. Through a series of measures, including the special recruitment of NHS nurses (with additional pay) and the use of Swiss sanatoria, the waiting list for hospital beds had declined. -

Scottish Tories at Mid-Term

SCOTTISH TORIES AT MID-TERM: A REVIEW OF SCOTTISH OFFICE MINISTERS AND POLICIES 1979-81 Robert McCreadie, Lecturer in Scots Law, University o£ Edinburgh Starting Afresh In May 1979 the British, but not the Scottish, electorate voted into power an administration which had stated its dislike o£ the principles o£ collectivism and welfare more firmly than any o£ its post-war predecessors. The wheel o£ government was to be pulled hard down to the right, not only widening the gul£ between the La bour and Conservative Parties but also making explicit the diver gence within the latter between the stern, penny-pinching apostles o£ Milton Friedman- economic superstar o£ the Eighties - and the somewhat shop-soiled pragmatists left over £rom the Heath era. During the euphoria which can a££lict even time-served politicians at the moment o£ victory, Margaret Thatcher, entering No. 10 Down ing Street £or the first time as Prime Minister, felt moved to un burden herself o£ the famous words o£ St. Francis o£ Assisi: "Where there is discord may we bring harmony; where there is doubt may we bring faith". But her message o£ "pax vobiscum", delivered low-key in that recently-created Saatchi and Saatchi voice, could conceal only momentarily her steely determination to take on Social ist and Tory alike in her drive to implement her monetarist doc trines. For her, the control o£ inflation required that firm brakes llllilllii be applied to public spending,while the raising o£ incentives and productivity, demanded substantial cuts in taxation. Translated into action, these policies struck not only at the heart o£ the socialist creed but also at the middle ground in politics. -

1966-Pages.Pdf

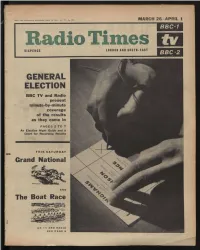

THE GENERAL On Thursday night and Friday morning the BBC both in Television and Radio will be giving you the fastest possible service of Election Results. Here David Butler, one of the expert commentators on tv, explains the background to the broadcasts TELEVISION A Guide for Election Night AND RADIO 1: Terms the commentators use 2: The swing and what it means COVERAGE THERE are 630 constituencies in the United Kingdom in votes and more than 1,600 candidates. The number of seats won by a major is fairly BBC-1 will its one- party begin compre- DEPOSIT Any candidate who fails to secure exactly related to the proportion of the vote which hensive service of results on eighth (12.5%), of the valid votes in his constituency it wins. If the number of seats won by Liberals and soon after of L150. Thursday evening forfeits to the Exchequer a deposit minor parties does not change substantially the close. the polls STRAIGHT FIGHT This term is used when only following table should give a fair guide of how the At the centre of operations two candidates are standing in a constituency. 1966 Parliament will differ from the 1964 Parlia- in the Election studio at ment. (In 1964 Labour won 44.1% of vote and huge MARGINAL SEATS There is no precise definition the TV Centre in London will be 317 seats; Conservatives won 43.4 % of the vote and of a marginal seat. It is a seat where there was a Cliff Michelmore keeping you 304 seats; Liberals 11.2% of the vote and nine seats small majority at the last election or a seat that in touch with all that is �a Labour majority over all of going is to change hands. -

Arkm Rev.Qxd

Faith in Diplomacy Archie Mackenzie A memoir CAUX BOOKS • GROSVENOR BOOKS In this well-written book containing accounts of many delightful episodes in his diplomatic life, Archie Mackenzie succeeds in combining his working principles with his deeply held beliefs in Moral Re-Armament. He describes the problems he encountered right up to the highest level in his profession and how he succeeded in overcoming them throughout his long service in Whitehall and in our Embassies abroad. I know of no one else who has done this so capably and it makes both enjoyable and impressive reading. Edward Heath, KG, PC, British Prime Minister 1970-74 Archie Mackenzie is a diplomat with a long memory. His knowledge of the UN goes back to 1945, and I was fortunate enough to have him as head of the economic work of the Mission when I became Ambassador in 1974. A man of deep personal integrity, which showed in his professional activities, he was a diplomat of the highest quality. His story is well worth the telling. Ivor Richard, PC, QC, British Ambassador to UN 1974-80, Leader of the House of Lords, Labour Government, 1997-98 The distillation from a life-time of creative service by a Western diplomat identifying with all parts of the world. Rajmohan Gandhi, Indian writer and political figure Archie Mackenzie’s book is about faith, diplomacy, and personal fulfilment. It is a testament of gratitude for a life of purpose and service. Its author’s life has been shaped by the way in which he found practical expression for his Christian faith. -

The Persecution of Ruth and Seretse Khama

A marriage of inconvenience: the persecution of Ruth and Seretse Khama http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10019 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org A marriage of inconvenience: the persecution of Ruth and Seretse Khama Author/Creator Dutfield, Michael Publisher U. Hyman (London) Date 1990 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Botswana, United Kingdom Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968.1 S483Zd Rights By kind permission of Heather Dutfield. Description The story of the marriage of Ruth Williams, a white "English girl", and Seretse Khama, an African prince from the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, present-day Botswana. -

Young-FAI-2016-The-Evolution-Of-The

FORTY TURBULENT YEARS How the Fraser Economic Commentary recorded the evolution of the modern Scottish economy Alf Young Visiting Professor, International Public Policy Institute, University of Strathclyde 1 Table of Contents 2 Preface 5 Part 1: 1975 – 1990: Inflation, intervention and the battle for corporate independence 14 Part 2: 1991 – 2000: From recession to democratic renewal via privatisation and fading silicon dreams 25 Part 3: 2001 – 2015: The ‘Nice’ decade turns nasty; banking Armageddon; and the politics of austerity 36 Postscript Alf Young, Visiting Professor, International Public Policy Institute, University of Strathclyde 2 PREFACE HEN the University of Strathclyde’s Fraser of Allander Institute, together with its Economic Commentary, was first launched in 1975, its arrival was made W possible by substantial philanthropic support from a charitable foundation that bore the Fraser family name. The Fraser Foundation (now the Hugh Fraser Foundation) continues to dispense support to deserving causes to this day. It represents the lasting public legacy of one of post-war Scotland’s major men of commerce. Hugh Fraser - Lord Fraser of Allander - created the House of Fraser department store empire, incorporating as its flagship emporium the up-market Harrods in London’s Knightsbridge. And through his commercial holding company, Scottish & Universal Investments or SUITs, Fraser controlled many other diverse Scottish businesses from knitwear production to whisky distilling. In 1964, after a titanic takeover battle with Roy Thomson, the Canadian-born owner, since the 1950s, of the Scotsman newspaper and the commercial Scottish Television franchise, the soon-to-be-enobled Fraser, through SUITs, took control of Outram, publisher of The Glasgow Herald and a stable of local Scottish newspapers. -

Watt Library, Greenock

Watt Library, Greenock Newspaper Index This index covers stories that have appeared in newspapers in the Greenock, Gourock and Port Glasgow area from the start of the nineteenth century. It is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Subject Entry Newspaper Date Page O' Connell, Daniel Report of speech by Mr O'Connell at his meeting in Greenock Greenock Advertiser 24/09/1835 2 Oatmeal Mills Oatmeal mill on Cartsburn to be let. Greenock Advertiser 09/05/1817 1 Observatories Article on the observatory in Newton Street built by John Heron in 1819 Greenock Telegraph 05/10/1976 4 Ocean Steamship Co. List of Greenock built steamers for Ocean Steamship Co., Liverpool Greenock Telegraph 08/12/1892 2 Oceanspan Reactions to Sir William Lithgow's plan to make the Clyde Europe's top deep-water Greenock Telegraph 27/03/1970 7 port Octavia Cottages, Greenock Photograph of Octavia Cottages c1900. Known as Mains Farm - 4.12.81 p12 Greenock Telegraph 17/11/1981 5 Octavia Court, Greenock Inquiry wanted after complaints about conditions at Octavia Court Greenock Telegraph 22/04/1978 7 Octavia Hall, Greenock Opening of new skating rink in the Octavia Hall. Greenock Advertiser 23/10/1877 2 Octavia Hall, Greenock Uncovering of the halls at 92-94 West Blackhall Street. Further information - 21st Sept Greenock Telegraph 08/09/1978 8 p10 Odd Fellows Tavern, Odd Fellows Tavern, 11 Market Street opened