Queen Christina of Sweden's Development of a Classical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Contact and Acculturation in New Sweden 1638-1655

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1983 Culture Contact and Acculturation in New Sweden 1638-1655 Glenn J. Jessee College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jessee, Glenn J., "Culture Contact and Acculturation in New Sweden 1638-1655" (1983). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624398. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-stfg-0423 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURE CONTACT AND ACCULTURATION IN NEW SWEDEN 1638 - 1655 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Glenn J. Jessee 1983 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved, May 1983 _______________ AtiidUL James Axtell James WhdJttenburg Japres Merrell FOR MY PARENTS iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ....................................................... v INTRODUCTION .................................................. 2 CHAPTER I. THE MEETING OF CULTURES ......................... -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

'A Ffitt Place for Any Gentleman'?

‘A ffitt place for any Gentleman’? GARDENS, GARDENERS AND GARDENING IN ENGLAND AND WALES, c. 1560-1660 by JILL FRANCIS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to investigate gardens, gardeners and gardening practices in early modern England, from the mid-sixteenth century when the first horticultural manuals appeared in the English language dedicated solely to the ‘Arte’ of gardening, spanning the following century to its establishment as a subject worthy of scientific and intellectual debate by the Royal Society and a leisure pursuit worthy of the genteel. The inherently ephemeral nature of the activity of gardening has resulted thus far in this important aspect of cultural life being often overlooked by historians, but detailed examination of the early gardening manuals together with evidence gleaned from contemporary gentry manuscript collections, maps, plans and drawings has provided rare insight into both the practicalities of gardening during this period as well as into the aspirations of the early modern gardener. -

Portrait Dated 1512, at the State Hermitage Museum1

542 Giovanna Perini Folesani УДК: 75.041.5 ББК: 85.103(4)5 А43 DOI: 10.18688/aa177-5-55 Giovanna Perini Folesani Dominicus Who? Solving the Riddle Posed by a Splendid “Venetian” Portrait Dated 1512, at the State Hermitage Museum1 It takes some real quality for a Renaissance portrait to be able to hang close to Giorgione’s Judith in the same museum room without fading or being overshadowed2 (Ill. 124). The high quality of this problematic picture is further proven by its seventeenth-century attribution to Giorgione (who died two years before it was painted) [70, I, p. 105; 15, p. 190]. It is no coinci- dence that this very portrait was chosen for the dust-jacket of the official catalogue in English of the Venetian paintings in the State Hermitage Museum published in the 1990s [31] and has recently travelled to Australia along with other masterpieces from St. Petersburg3. Still, its attri- bution and iconography have proven elusive so far. Its current, yet not undisputed attribution to Domenico Capriolo, a minor Giorgionesque painter, is untenable on both stylistic and historical grounds4. A comparison with his one undis- puted portrait of Lelio Torelli, signed and dated 1528 [23, XIX, pp. 210–211; 87, V, pp. 557–558; 77, XVI, pp. 281–282; 89, IX/3, p. 548, fig. 374], shows that sixteen years later, far from im- proving as an artist, Domenico Capriolo (if he were the author of the State Hermitage picture) would paint in a stiffer, more elementary, much less imaginative and elegant way, having but a clumsy grasp on perspective. -

A Systematic Concept Exploration Methodology Applied to Venus in Situ Explorer

Session III: Probe Missions to the Giant Planets, Titan and Venus A Systematic Concept Exploration Methodology Applied to Venus In Situ Explorer Jarret M. Lafleur *, Gregory Lantoine *, Andrew L. Hensley *, Ghislain J. Retaureau *, Kara M. Kranzusch *, Joseph W. Hickman *, Marc N. Wilson *, and Daniel P. Schrage † Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia 30332 ABSTRACT One of the most critical tasks in the design of a complex system is the initial conversion of mission or program objectives into a baseline system architecture. Presented in this paper is a methodology to aid in this process that is frequently used for aerospace problems at the Georgia Institute of Technology. In this paper, the methodology is applied to initial concept formulation for the Venus In Situ Explorer (VISE) mission. Five primary steps are outlined which encompass program objective definition through evaluation of candidate designs. Tools covered include the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), and morphological matrices. Direction is given for the application of modeling and simulation as well as for subsequent iterations of the process. The paper covers both theoretical and practical aspects of the tools and process in the context of the VISE example, and it is hoped that this methodology may find future use in interplanetary probe design. 1. INTRODUCTION One of the most critical tasks in the design of a complex engineering system is the initial conversion of mission or program objectives and requirements into a baseline system architecture. In completing this task, the challenge exists to comprehensively but efficiently explore the global trade space of potential designs. -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

SFSC Search Down to 4

C M Y K www.newssun.com EWS UN NHighlands County’s Hometown-S Newspaper Since 1927 Rivalry rout Deadly wreck in Polk Harris leads Lake 20-year-old woman from Lake Placid to shutout of AP Placid killed in Polk crash SPORTS, B1 PAGE A2 PAGE B14 Friday-Saturday, March 22-23, 2013 www.newssun.com Volume 94/Number 35 | 50 cents Forecast Fire destroys Partly sunny and portable at Fred pleasant High Low Wild Elementary Fire alarms “Myself, Mr. (Wally) 81 62 Cox and other administra- Complete Forecast went off at 2:40 tors were all called about PAGE A14 a.m. Wednesday 3 a.m.,” Waldron said Wednesday morning. Online By SAMANTHA GHOLAR Upon Waldron’s arrival, [email protected] the Sebring Fire SEBRING — Department along with Investigations into a fire DeSoto City Fire early Wednesday morning Department, West Sebring on the Fred Wild Volunteer Fire Department Question: Do you Elementary School cam- and Sebring Police pus are under way. Department were all on think the U.S. govern- The school’s fire alarms the scene. ment would ever News-Sun photo by KATARA SIMMONS Rhoda Ross reads to youngsters Linda Saraniti (from left), Chyanne Carroll and Camdon began going off at approx- State Fire Marshal seize money from pri- Carroll on Wednesday afternoon at the Lake Placid Public Library. Ross was reading from imately 2:40 a.m. and con- investigator Raymond vate bank accounts a children’s book she wrote and illustrated called ‘A Wildflower for all Seasons.’ tinued until about 3 a.m., Miles Davis was on the like is being consid- according to FWE scene for a large part of ered in Cyprus? Principal Laura Waldron. -

The History and Development of Groves in English Formal Gardens

This is a repository copy of The history and development of groves in English formal gardens. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/120902/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Woudstra, J. orcid.org/0000-0001-9625-2998 (2017) The history and development of groves in English formal gardens. In: Woudstra, J. and Roth, C., (eds.) A History of Groves. Routledge , Abingdon, Oxon , pp. 67-85. ISBN 978-1-138-67480-6 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The history and development of groves in English formal gardens (1600- 1750) Jan Woudstra It is possible to identify national trends in the development of groves in gardens in England from their inception in the sixteenth century as so-called wildernesses. By looking through the lens of an early eighteenth century French garden design treatise, we can trace their rise to popularity during the second half of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century to their gradual decline as a garden feature during the second half of the eighteenth century. -

2 Die Geschichte Der Goten Bei Cassiodorus Und Jordanes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Römische Gotenpolitik von den Anfängen bis zum Tod von Theodosius I.“ Verfasser Daniel Hackhofer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 310 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde Betreuerin / Betreuer: emer. O. Univ. Prof. Dr. Gerhard Dobesch Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Zum Verständnis ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Inhalt und zeitlicher Rahmen ..................................................................................... 1 1.2 Zielsetzung ................................................................................................................. 1 2 Die Geschichte der Goten bei Cassiodorus und Jordanes .................................................. 2 2.1 Die Kontroverse um Bedeutung und Wert der Getica als Quelle .............................. 2 2.2 Argumente .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2.1 Jordanes .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2.2 Die Entstehung der Getica ...................................................................................... 4 2.2.3 Cassiodorus und seine verlorene Gotengeschichte ............................................... -

Swedish American Genealogist

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 5 | Number 3 Article 1 9-1-1985 Full Issue Vol 5 No. 3 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1985) "Full Issue Vol 5 No. 3," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 5 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol5/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (ISSN 0275-9314) Swedish American Genealo ist A journal devoted to Swedish American biography, genealogy and personal history CONTENTS Swedish Parish Records on Microfiche 97 The Search for Johan Petter Axelsson's Father IOI Swedish Emigration to North America via Hamburg 1850-1870 106 Carl Johan Ahlmark - Early Swede in Louisville, KY 109 John Martin Castell - Early Swedish Gold Miner 115 A Swedish Passenger List from 1902. II 118 A Note on Sven Aron Ponthan 121 The Sylvanders of Lowell and Taunton, MA 124 Literature 127 Ancestor Tables I 29 Genealogical Queries 137 Vol. V September 1985 No. 3 Swedish American Genealogist~ Co pyright © 198 5 SH ecli.,h A men can (je11ealuR1,,·1 P.O. Box 21X6 Wint er Park. FL 32790 (I\S, ()c 7. 5-l/ 1 -li J::d itor and Publisher "i ii, Willi am Olss on. Ph.D .. F.i\.S .G Contributing E ditors Glen E. -

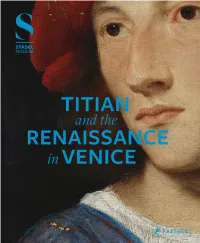

VENETIAN PAINTING in the AGE of TITIAN P

TITIAN and the RENAISSANCE inVENICE EDITED BY BASTIAN ECLERCY AND HANS AURENHAMMER WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY MARIA ARESIN HANS AURENHAMMER ANDREA BAYER ANNE BLOEMACHER DANIELA BOHDE BEVERLY LOUISE BROWN STEFANIE COSSALTERDALLMANN BENJAMIN COUILLEAUX HEIKO DAMM RITA DELHÉES JILL DUNKERTON BASTIAN ECLERCY MARTINA FLEISCHER IRIS HASLER FREDERICK ILCHMAN ROLAND KRISCHEL ANN KATHRIN KUBITZ ADELA KUTSCHKE SOFIA MAGNAGUAGNO TOM NICHOLS TOBIAS BENJAMIN NICKEL SUSANNE POLLACK VOLKER REINHARDT JULIA SAVIELLO FRANCESCA DEL TORRE SCHEUCH CATHERINE WHISTLER AND MATTHIAS WIVEL PRESTEL MUNICH · LONDON · NEW YORK TITIAN and the RENAISSANCE inVENICE EDITED BY BASTIAN ECLERCY AND HANS AURENHAMMER WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY MARIA ARESIN, HANS AURENHAMMER, ANDREA BAYER, ANNE BLOEMACHER, DANIELA BOHDE, BEVERLY LOUISE BROWN, STEFANIE COSSALTER-DALLMANN, BENJAMIN COUILLEAUX, HEIKO DAMM, RITA DELHÉES, JILL DUNKERTON, BASTIAN ECLERCY, MARTINA FLEISCHER, IRIS HASLER, FREDERICK ILCHMAN, ROLAND KRISCHEL, ANN KATHRIN KUBITZ, ADELA KUTSCHKE, SOFIA MAGNAGUAGNO, TOM NICHOLS, TOBIAS BENJAMIN NICKEL, SUSANNE POLLACK, VOLKER REINHARDT, JULIA SAVIELLO, FRANCESCA DEL TORRE SCHEUCH, CATHERINE WHISTLER AND MATTHIAS WIVEL PRESTEL MUNICH · LONDON · NEW YORK 2 CONTENTS GREETINGS POESIA AND MYTH p. 8 Painting as Poetry p. 108 FOREWORD Philipp Demandt BELLE DONNE p. 10 Idealised Images of Beautiful Women p. 126 Essays GENTILUOMINI Portraits of Noblemen VENETIAN PAINTING IN THE AGE OF TITIAN p. 150 Hans Aurenhammer p. 16 COLORITO ALLA VENEZIANA Colour, Coloration and the Trade in Pigments PAINTING TECHNIQUES IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY VENICE p. 184 Jill Dunkerton p. 28 FLORENCE IN VENICE The Male Nude VENICE IN THE RENAISSANCE. p. 204 A SOCIAL AND POLITICAL PROFILE Volker Reinhardt EPILOGUE p. 38 The Impact of the Venetian Renaissance in Europe from El Greco to Thomas Struth p. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth.