Yoma 85B MISHNA: a Sin-Offering, Which Atones for Unwitting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KS 3 Talmud Page Layout Copy

Page Chapter name Tractate name Chapter number Ein mishpat, Ner mitzvah Rashi’s commentary –Rashi (an acronym for Rabbi (Hebrew: Well of justice, Lamp of Shlomo Yitchaki) was a major Jewish scholar active in the commandment) Compiled in 11th century France. Rashi compiled the first the 16th century this provides the complete commentary on the Talmud. The Mishnah source references to the laws are written in in a brief, terse style without being discussed on the page. punctuation and Rashi’s commentary is directed towards helping readers work through the text and understand its basic form and content. Tosafot (Hebrew: additions) These Mishnah and Gemara The central column of the page contains medieval commentaries were written in verses of the Mishnah followed by verses from the Gemara. the 12th and 13th centuries. They are the The Mishnah is the primary record of the teaching, decisions work of various Talmudic scholars and disputes of a group of Jewish religious and judicial scholars primarily living in France and Germany. known as Tannaim, active from about 10 to 220 CE. Originally transmitted orally, it was edited into its current form and written down in 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi. Written primarily in Hebrew, it is divided into 63 tractates and organized into six sections or ‘orders’. The Gemara is an analysis and expansion on the Mishnah. There are two versions - the Other commentaries Various other Babylonian Talmud (the most commonly studied) and the commentaries appear in the margins Jerusalem Talmud. The Gemara is written primarily in Aramaic of a printed Talmud page. -

Yoma Book.Indb

Perek V Daf 56 Amud a BACKGROUND ten log that I will later separate shall be the fi rst tithe;N and another ֲﬠ ָׂשָרה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר ִר ׁאשוֹן, ִּת ׁ ְש ָﬠה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר Terumot and tithes : ְּת ּרומוֹת ּו ַמ ַﬠ ְׂשרוֹת – tenth from the rest, which equals nine log of the remaining ninety, Terumot and tithes are separated in the following manner. For example, if one ׁ ֵש ִני, ּו ֵמ ֵיחל ְו ׁש ֶוֹתה ִמ ָיּד, ִ ּד ְבֵרי ַר ִּבי -shall be second tithe. And he redeems the second tithe with money has one hundred units of food or beverage, he first re ֵמ ִאיר. that he will later take to Jerusalem, and he may then immediately moves the teruma gedola, which is given to the priests. The N drink the wine. Aft er Shabbat, when he removes portions from the average amount of this gift is one-fiftieth of the produce, mixture and places them in vessels, they are retroactively designated which in this example is two units. Next, the first tithe is B as terumot and tithes. Th is is the statement of Rabbi Meir. removed and given to a Levite. This gift is ten percent of the remaining produce, or slightly less than ten units in this case. In most years, another tenth is taken from the rest as second tithe, which is taken to Jerusalem and consumed there. Here the second tithe amounts to slightly more than nine units. In years three and six of the Sabbatical cycle, this tithe is given to the poor instead. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life

Wed 6 May 2020 / 12 Iyar 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Adult Education Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life Introduction Judaism enjoins us to save lives. The Torah says: You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor. [Leviticus 19:16] and ּושְׁמַרְׁתֶֶּ֤םאֶת־חֻקֹּתַי֙ וְׁאֶ ת־מִשְׁ פָּטַַ֔ יאֲשֶֶׁ֨ ר יַעֲשֶ ֶׂ֥ ה אֹּתָּ ָ֛ם הָּאָּדָּ ָ֖ם וָּחַ ַ֣י בָּהֶ ֶ֑םאֲנִ ָ֖ייְׁהוָָּֽה You shall therefore keep my statutes and my ordinances, which, if a man performs, he shall live by them. I am the Lord. [Leviticus 18:5] These words were echoed much later by the prophet Ezekiel. [Ezekiel 20:11] The Talmud derives from the verse “you shall live by them” that Jews must live by the Torah and not die because of it. This is the doctrine of Pikuach regard for human life. Even if you must break -- (פִ קּוחַ נֶפש) Nefesh commandments to save a life (yours or another's), do so. Alternate Talmudic logic: The objective is to maximize observance of commandments. Allowing someone to live increases the number of commandments observed. Example: Violating Shabbat to save someone allows him to observe other Shabbatot in the future. [Yoma 85b, Shabbat 151b] Mishna: If uncertain whether life is truly in danger, err on the side of assuming it is. [Yoma 8:6] If turns out there was no threat to human life, no sin and no reason to feel guilty. How far can you go? The Talmud says that healing is prohibited on Shabbat because you need to crush herbs to make medicine, and crushing is prohibited on Shabbat. -

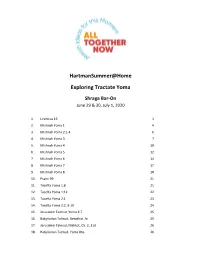

Hartmansummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma

HartmanSummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma Shraga Bar-On June 29 & 30, July 1, 2020 1. Leviticus 16 1 2. Mishnah Yoma 1 4 3. Mishnah Yoma 2:1-4 6 4. Mishnah Yoma 3 7 5. Mishnah Yoma 4 10 6. Mishnah Yoma 5 12 7. Mishnah Yoma 6 14 8. Mishnah Yoma 7 17 9. Mishnah Yoma 8 18 10. Psalm 99 21 11. Tosefta Yoma 1:8 21 12. Tosefta Yoma 1:12 22 13. Tosefta Yoma 2:1 23 14. Tosefta Yoma 2:2, 9-10 24 15. Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 3:7 25 16. Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 7a 25 17. Jerusalem Talmud, Makkot, Ch. 2, 31d 26 18. Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 86a 26 The Shalom Hartman Institute is a leading center of Jewish thought and education, serving Israel and North America. Our mission is to strengthen Jewish peoplehood, identity, and pluralism; to enhance the Jewish and democratic character of Israel; and to ensure that Judaism is a compelling force for good in the 21st century. Share what you’re learning this summer! #hartmansummer @SHI_america shalomhartmaninstitute hartmaninstitute 475 Riverside Dr., Suite 1450 New York, NY 10115 212-268-0300 [email protected] | shalomhartman.org 1. Leviticus 16 )א( ַוְיַדֵּבר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַאֲחֵּרי מֹות ְשֵּני ְבֵּני ַאֲהֹרן ְבָקְרָבָתם ִלְפֵּני ה' ַוָיֻמתּו: )ב( ַויֹאֶמר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַדֵּבר ֶאל ַאֲהֹרן ָאִחיָך ְוַאל ָיבֹא ְבָכל ֵּעת ֶאל ַהֹקֶדש ִמֵּבית ַלָפֹרֶכת ֶאל ְפֵּני ַהַכֹפֶרת ֲאֶשר ַעלָ הָאֹרןְ ולֹאָ ימּות ִכי ֶבָעָנן ֵּאָרֶאה ַעלַהַכֹפֶרת: )ג( ְבזֹאתָיבֹא ַאֲהֹרן ֶאלַהֹקֶדש ְבַפר ֶבן ָבָקר ְלַחָטאת ְוַאִיל ְלֹעָלה: )ד( ְכֹתֶנת ַבד ֹקֶדש ִיְלָבש ּוִמְכְנֵּסי ַבד ִיְהיּו ַעל ְבָשרֹו ּוְבַאְבֵּנט ַבד ַיְחֹגר ּוְבִמְצֶנֶפת -

The Missing 168 Years - Part 1 Ou Israel Center - Winter 2019

5779 - bpipn mdxa` [email protected] 1 c‡qa HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 117 - THE MISSING 168 YEARS - PART 1 OU ISRAEL CENTER - WINTER 2019 A] TRADITIONAL JEWISH CHRONOLOGY - SEDER OLAM (S.O.) A1] EXILE AND REBUILDING d«G¤d© mŸewO¨d©Îl`¤ mk¤½ z§ `¤ aiW´¦ d¨l§ aŸeH½ d© ix´¦a¨C§Îz`¤ Æmk¤i¥l£r i³z¦ Ÿnw¦ d£e© m®k¤z§ `¤ cŸw´t§ `¤ d¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ l²a¤a¨l§ z`Ÿ¯ln§ itº¦ l§ iM¦Â 'd x´n©`¨ ÆdŸkÎiM«¦ 1. i:hk edinxi Yirmiyahu prophecies that the exile in Bavel will last 70 years before the people are brought back to Eretz Yisrael. mix®¦t¨Q§ A© iz¦ ŸpiA¦ l`¥I½p¦C«¨ Æip¦`£ Ÿek½ l§ n¨l§ Æzg©`© z³p©W§ A¦ :miC«¦U§ M© zEk¬ l§ n© lr© K©l½ n§ d¨ x´W¤ `£ i®c¨n¨ rx©´G¤n¦ WŸexe¥W§ g©`£ÎoA¤ W¤e²¨ix§c¨l§ zgÀ©`© z´p©W§ A¦ 2. d«¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ m©l¦ W¨ Exi§ zŸea¬ x§g¨l§ ze`Ÿ²Nn©l§ `ia½¦ ¨Pd© d´¨in¦ x§i¦Îl`¤ 'dÎxa©c§ d³¨id¨ xW¸¤ `£ mipÀ¦X¨ d© x´R©q§ n¦ a-`:h l`ipc Daniel, immersed in the exile in Bavel in the first year of the reign of Darius, son of Achashverosh, also understands from his reading of Nach that the exile should only last 70 years. d«¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ df¤ dY¨n§ r©½ f¨ x´W¤ `£ d®c¨Edi§ i´x¥r¨ z`¥e§ m¦©l½ W¨ Exi§Îz`¤ m´g¥x©z§ Î`Ÿl« ÆdY¨`© iz©À n¨Îcr© zŸe`½ a¨v§ 'd x¼n©`ŸIe© 'dÎK`©l§ n© or©´I©e© 3. -

The Sea of Talmud: a Brief and Personal Introduction

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2012 The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry M. Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. M. (2012). The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEA OF TALMUD A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry Abramson Published by Parnoseh Books at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Henry Abramson Cover photograph by Steven Mills. No Talmud volumes were harmed during the photo shoot for this book. Smashwords Edition, License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment and information only. This ebook should not be re-sold to others. Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute this ebook for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided the book remains in its complete original form. Version 3.1 June 18, 2012. To my students All who thirst--come to the waters Isaiah 55:1 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One: Our Talmud Chapter Two: What, Exactly, is the Talmud? Chapter Three: The Content of the Talmud Chapter Four: Toward the Digital Talmud Chapter Five: “Go Study” For Further Reading Acknowledgments About the Author Introduction The Yeshiva administration must have put considerable thought into the wording of the hand- lettered sign posted outside the cafeteria. -

The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5bx332x5 Author Septimus, Zvi Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions by Zvi Septimus A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Professor David Henkin Professor Naomi Seidman Spring 2011 The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions Copyright 2011 All rights reserved by Zvi Septimus Abstract The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions by Zvi Septimus Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair This dissertation proposes a poetics and semiotics of the Bavli (Babylonian Talmud)—how the Bavli, through a complex network of linguistic signs, acts on its implied reader's attempt to find meaning in the text. In doing so, I advance a new understanding of how the Bavli was composed, namely as a book written by its own readers in the act of transmission. In the latter half of the twentieth century, Bavli scholarship focused on the role of the Stam (the collective term for those people responsible for the anonymous voice of the Bavli) in the construction of individual Bavli passages (sugyot). -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

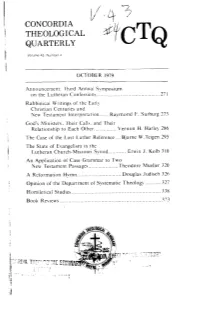

Rabbinical Writings of the Early Christian Centuries and New Testament Interpretation Raymond F

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY I Volume 43, Number 4 i2nnouncernent: -1 hird Annual Symposium on the Lutheran Confessions> ............................................ 27 1 Rabbinical Lb'r-itings of the Early Christian Centuries and New Testament inter-pretat;on ....... Ravmond F. Surburg 273 God's Ministers. Their Calls. and Their Relationship to Each Other ................ Vefnon H. Harley 286 The Case of the Lost Luther Reference ... Bjar-ne lV.Teigen 295 The State of Evangelisr~lin the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod ............ Er~.inJ. Kolb 3 10 An AppIication of' Case Grammar to Two New Testament Passages ..................... Theodore Mueller 320 A Reformation Hymn ............................... Douglas Judisch 326 Opinion of the Department ol Systematic Theolop). ........... 327 Homiletical Studies .............................................................. 338 Book Reviews ...................................................................... -773 Rabbinical Writings of the Early Christian Centuries and New Testament Interpretation Raymond F. Surburg Both Christians and Jews have the Old Testament as a feature of their respective faiths. Christianity utilizes as its authority the Old Testament and the New Testament. Judaism relies for its teachings upon the Old Testament and the Talmud. By the year A.D. 70 the cleavage between Christianity and Judaism may be said to have been finalized.With the destruction of Jerusalem and its sacred Temple the break between Judaism and Christianity was final. By the end of the first Christian century the New Testa- ment canon was complete and the direction that Christianity took was permanently determined. Certain Jewish writings which came to be written in the first and second centuries A. D. likewise determined the permanent course of Judaism. The Talmud is the primary major source for the understanding of Judaism. -

Rabbinic Judaism “Moses Received Torah F

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project Introduction – Rabbinic Judaism “Moses received Torah from Sinai and handed it down to Joshua; and Joshua to the Elders; and the Elders to the Prophets; and the Prophets handed it down to the Men of the Great Assembly…” Mishnah Avot 1:1 Judaism is often believed to be a religion based primarily in the Hebrew Bible, or even more specifically, the first five books of the Bible, known in Jewish tradition as the Torah. These five books, in the form of a Torah scroll, are found in nearly every Jewish house of worship. “Torah,” however, is a term whose meaning can encompass far more than particular books; for Jews, “Torah” often also means the full scope of Jewish learning, law, practice, and tradition. This conception of Torah derives from the rabbis of late antiquity, who developed the belief that the written Torah was accompanied from its earliest transmission by an equally Divine “Oral Torah,” a body of law and explanations of the written Torah that was passed down by religious leaders and scholars through the ages of Jewish history. Thus, Jewish law and religious practices are based in far more than the biblical text. The rabbis considered themselves an integral link in this chain of transmission, and its heirs. In particular, the works produced by the rabbis of late antiquity, from the beginning of the Common Era to the time of the Muslim Conquest, in Roman Palestine and Sassanian Babylonia (modern day Iran/Iraq), have influenced the shape of Judaism to this day. The Talmud (defined below), for example, is considered the essential starting point for any discussion of Jewish law, even more so than the bible. -

What Is the Aggadah Problem?

Chapter 1 Ļ ļ What Is the Aggadah Problem? he term aggadah is so widely used in the Talmud and early related literature that one would think it easy to ascertain its meaning. But the Talmudic masters do not provide us with formal definitions of their procedural terms. As it T were, they seem too busy with their Torah work to step away from it and initiate outsiders into the nature of their analytic tools. Their terminological pragmatics was emulated by those who transmitted their teachings and the redactors who reduced these oral records to the written texts we still study. Since the rabbinic study tradition has never died out, this practice is, to a considerable extent, satisfactory. But particularly for those interested in how the rabbis thought about their belief—their “philosophizing” in a quite loose sense of the word—this absence of definition is disturbing and barely re- lieved by the common expedient of defining aggadah in terms of what it is not, namely, that it is Jewish law’s nonlegal accompaniment. A philological approach to a positive understanding does not help us much. Though the Hebrew root of the term, n-g-d, is well attested in the Bible and carries the primary meaning of “tell,” the noun form with its collective sense appears only in rabbinic literature. Wilhelm Bacher’s pioneering efforts to trace a path from the biblical “telling” to the polysemy of the rabbinic usage has not convinced most later schol- ars and their several alternative proposals have themselves not re- solved the issue.1 Turning to the Talmud, we quickly encounter a reason for some of this terminological indeterminacy when we look at the use of the Hebrew version of this term, haggadah.