Yoma Book.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life

Wed 6 May 2020 / 12 Iyar 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Adult Education Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life Introduction Judaism enjoins us to save lives. The Torah says: You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor. [Leviticus 19:16] and ּושְׁמַרְׁתֶֶּ֤םאֶת־חֻקֹּתַי֙ וְׁאֶ ת־מִשְׁ פָּטַַ֔ יאֲשֶֶׁ֨ ר יַעֲשֶ ֶׂ֥ ה אֹּתָּ ָ֛ם הָּאָּדָּ ָ֖ם וָּחַ ַ֣י בָּהֶ ֶ֑םאֲנִ ָ֖ייְׁהוָָּֽה You shall therefore keep my statutes and my ordinances, which, if a man performs, he shall live by them. I am the Lord. [Leviticus 18:5] These words were echoed much later by the prophet Ezekiel. [Ezekiel 20:11] The Talmud derives from the verse “you shall live by them” that Jews must live by the Torah and not die because of it. This is the doctrine of Pikuach regard for human life. Even if you must break -- (פִ קּוחַ נֶפש) Nefesh commandments to save a life (yours or another's), do so. Alternate Talmudic logic: The objective is to maximize observance of commandments. Allowing someone to live increases the number of commandments observed. Example: Violating Shabbat to save someone allows him to observe other Shabbatot in the future. [Yoma 85b, Shabbat 151b] Mishna: If uncertain whether life is truly in danger, err on the side of assuming it is. [Yoma 8:6] If turns out there was no threat to human life, no sin and no reason to feel guilty. How far can you go? The Talmud says that healing is prohibited on Shabbat because you need to crush herbs to make medicine, and crushing is prohibited on Shabbat. -

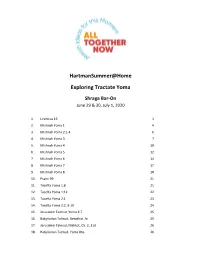

Hartmansummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma

HartmanSummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma Shraga Bar-On June 29 & 30, July 1, 2020 1. Leviticus 16 1 2. Mishnah Yoma 1 4 3. Mishnah Yoma 2:1-4 6 4. Mishnah Yoma 3 7 5. Mishnah Yoma 4 10 6. Mishnah Yoma 5 12 7. Mishnah Yoma 6 14 8. Mishnah Yoma 7 17 9. Mishnah Yoma 8 18 10. Psalm 99 21 11. Tosefta Yoma 1:8 21 12. Tosefta Yoma 1:12 22 13. Tosefta Yoma 2:1 23 14. Tosefta Yoma 2:2, 9-10 24 15. Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 3:7 25 16. Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 7a 25 17. Jerusalem Talmud, Makkot, Ch. 2, 31d 26 18. Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 86a 26 The Shalom Hartman Institute is a leading center of Jewish thought and education, serving Israel and North America. Our mission is to strengthen Jewish peoplehood, identity, and pluralism; to enhance the Jewish and democratic character of Israel; and to ensure that Judaism is a compelling force for good in the 21st century. Share what you’re learning this summer! #hartmansummer @SHI_america shalomhartmaninstitute hartmaninstitute 475 Riverside Dr., Suite 1450 New York, NY 10115 212-268-0300 [email protected] | shalomhartman.org 1. Leviticus 16 )א( ַוְיַדֵּבר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַאֲחֵּרי מֹות ְשֵּני ְבֵּני ַאֲהֹרן ְבָקְרָבָתם ִלְפֵּני ה' ַוָיֻמתּו: )ב( ַויֹאֶמר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַדֵּבר ֶאל ַאֲהֹרן ָאִחיָך ְוַאל ָיבֹא ְבָכל ֵּעת ֶאל ַהֹקֶדש ִמֵּבית ַלָפֹרֶכת ֶאל ְפֵּני ַהַכֹפֶרת ֲאֶשר ַעלָ הָאֹרןְ ולֹאָ ימּות ִכי ֶבָעָנן ֵּאָרֶאה ַעלַהַכֹפֶרת: )ג( ְבזֹאתָיבֹא ַאֲהֹרן ֶאלַהֹקֶדש ְבַפר ֶבן ָבָקר ְלַחָטאת ְוַאִיל ְלֹעָלה: )ד( ְכֹתֶנת ַבד ֹקֶדש ִיְלָבש ּוִמְכְנֵּסי ַבד ִיְהיּו ַעל ְבָשרֹו ּוְבַאְבֵּנט ַבד ַיְחֹגר ּוְבִמְצֶנֶפת -

Yoma 044.Pub

י"ד סיון תשפ“אTues, May 25 2021 OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) The prohibition against being in the sanctuary when Ketores atones for lashon hara יבא דבר שבחשאי ויכפר על מעשה חשאי the incense is burning A Baraisa explains the verse that teaches the prohibition against being in the Sanctuary when the incense is burning. T he ketores had the power to atone for lashon hara, for Rava explains how we know the verse refers to the time both are done quietly. Why is ketores considered to be a the incense is burning. quiet activity? Rashi (Arachim 16a) explains that the ketores which is a private place, away from , היכל Rava’s assertion that the incense effects atonement is is brought in the היכל unsuccessfully challenged. public view. In fact, no one was allowed to be in the A Mishnah rules that one is not allowed to be in the together with the kohen at the moment the ketores was area between the Ulam and the Altar while the incense is brought. Tosafos HaRosh proposes that perhaps the sprin- burning. kling of the blood of the bull of Yom Kippur should also be R’ Elazar explains that the Mishnah’s ruling applies only considered a private and quiet action, which should atone He . היכל when the incense is burned in the Sanctuary but not when for lashon hara, for it, too, was done in the it is burning in the kodesh kodoshim. answers that the sprinkling was done while the kohen R’ Elazar’s qualification is unsuccessfully challenged. -

Beginners Guide for the Major Jewish Texts: Torah, Mishnah, Talmud

August 2001, Av 5761 The World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) 9 Alkalai St., POB 4498 Jerusalem, 91045, Israel Tel: +972 2 561 0133 Fax: +972 2 561 0741 E-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.wujs.org.il Originally produced by AJ6 (UK) ©1998 This edition ©2001 WUJS – All Rights Reserved The Guide To Texts Published and produced by WUJS, the World Union of Jewish Students. From the Chairperson Dear Reader Welcome to the Guide to Texts. This introductory guide to Jewish texts is written for students who want to know the difference between the Midrash and Mishna, Shulchan Aruch and Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. By taking a systematic approach to the obvious questions that students might ask, the Guide to Texts hopes to quickly and clearly give students the information they are after. Unfortunately, many Jewish students feel alienated from traditional texts due to unfamiliarity and a feeling that Jewish sources don’t ‘belong’ to them. We feel that Jewish texts ought to be accessible to all of us. We ought to be able to talk about them, to grapple with them, and to engage with them. Jewish texts are our heritage, and we can’t afford to give it up. Jewish leaders ought to have certain skills, and ethical values, but they also need a certain commitment to obtaining the knowledge necessary to ensure that they aren’t just leaders, but Jewish leaders. This Guide will ensure that this is the case. Learning, and then leading, are the keys to Jewish student leadership. Lead on! Peleg Reshef WUJS Chairperson How to Use The Guide to Jewish Texts Many Jewish students, and even Jewish student leaders, don’t know the basics of Judaism and Jewish texts. -

Yoma 052.Pub

כ"ב סיון תשפ“אWed, Jun 2 2021 OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) The path into the Kodesh Kodoshim (cont.) Waiting until the ketores cloud fills the room צבר את הקטורת על גבי גחלים ותמלא כל הבית כולו עשן The Gemara finishes clarifying the opinions of R’ Yosi and R’ Yehudah regarding the path taken by the Kohen writes that (עבודת יום הכפורים פ“ ד ה“ א) Gadol to reach the Kodesh Kodoshim. ambam R 2) Amah traksin after spreading the ketores on the fry-pan, the Kohen R’ Nosson states that Chazal never determined wheth- Gadol should wait in the Kodesh Kodoshim until the of Mabit קרית ספר .er the area of the amah traksin was included as part of the room fills with a cloud of smoke Kodesh Kodoshim or the Sanctuary. explains that this opinion is based upon the verse it- Ravina challenges the assumption that the amah self, where we first find (Vayikra 16:13) that “the should be covered with the cloud,” and only כפורת -traksin was included in one of the two areas. He success fully demonstrates that it was considered an independent then does the procedure continue (ibid. v. 14) with domain and the only point of doubt was whether it was assigned the sanctity of the Kodesh Kodoshim or the sanc- the Kohen Gadol going out “to take from the blood tity of the Sanctuary. of the bull.” The doubt expressed by R’ Nosson is similar to a Nevertheless, throughout the year we do not find doubt expressed by R’ Yochanan in the name of Yosef the that the kohen who places the ketores on the golden man of Hutzal concerning a pasuk that describes the con- Altar must wait in the Sanctuary until the chamber struction of the Beis HaMikdash. -

Yom Kippur 5777

Written by: Zachary Citron Editor: David Michaels Yom Kippur 5777 Keeping an Eye on the Kohen Gadol: The image of the kohen gadol in the kodesh all opinions, having a cloud of incense in the kodesh kodashim was a prerequisite to kodashim on Yom Kippur is majestic and daunting, like the day itself. The holiest G-d’s presence there with the kohen gadol on Yom Kippur. But whereas the man, in the holiest place, on the holiest day, performing duties on which the fate of rabbis held that the incense should be placed on the firepan and burnt only once our people hangs. The poignancy is enhanced by the fact that, at the critical the kohen gadol was in the kodesh kadashim (as verse 13 implies), the Sadducees moments, the kohen gadol was alone with his Creator: as the verse says, “No man interpreted verse 2 such that the kohen gadol had to first create the incense cloud shall be in the tent of meeting when he comes to make atonement in the sanctuary outside the kodesh kodashim, and then enter it. until his departure...” (Vayikra 16, 17). The rabbis’ answer to the concern that a heretic kohen gadol, alone in the Over the course of the Yom Kippur prayers, we draw on this image for inspiration, sanctuary might go astray and follow the Sadducees, was to take him to an upper looking for moments to emulate, in our own small way, the kohen gadol’s intimacy chamber of the Temple (called Avtinas) on erev Yom Kippur and ensure that he with G-d. -

The Problem of Evil

THE PROBLEM OF EVIL: PART THREE: Talmudic Models Educator’s Guide and Sources Edited by Steve Israel and Noam Zion Based on lectures by Donniel Hartman For TICHON, the North American Jewish Day High Schools Program created by the Shalom Hartman Institute Experimental edition 2003, Jerusalem 5763 For internal use only 1 THE PROBLEM OF EVIL: RABBINIC RESPONSES I. Introduction: THE RABBINIC PERIOD Page 4 Opening Exercise: Can we recite with sincerity the last paragraph of the Birkat HaMazon? Page 6 II. GOD THE ACCOUNTANT: PROBLEMS WITH CALCULATING REWARD AND PUNISHMENT or THE “RICKETY LADDER” SYNDROME (TB Kiddushin 39b ) MISHNAH: THE SINGLE MITZVAH THEORY Page 8 GEMARA: THE ALTERNATIVE MISHNAH: Page 12 PRIVILEGED MITZVOT AS AN INVESTMENT IN OLAM HABA (Mishnah Peah 1:1) GOD THE ACCOUNTANT: Page 16 PROBLEMS WITH CALCULATING REWARD AND PUNISHMENT RABBI YAACOV’S PESSIMISM IN OLAM HAZEH : NO ILLUSIONS, NO EXPECTATIONS! Page 18 RABBI YAACOV’S OPPONENTS: Page 20 TALKING RABBI YAACOV OUT OF HIS PESSIMISM ABOUT OLAM HAZEH or DISMISSING THE STORY OF THE BOY WHO FELL OFF THE LADDER THE RICKETY LADDER DEFENSE: Page 25 LIMITED EXPECTATIONS FOR THIS WORLDLY PROVIDENCE THE MOST FAMOUS UNBELIEVER - ACHER : ELISHA BEN ABUYAH Page 27 III. THE WORLD HAS A WAY OF ITS OWN / OLAM K’MINHAGO NOHEIG (TB Avodah Zarah 54b) Page 30 INTRODUCTORY EXERCISE: A RELIGIOUS DISPUTATION Page 31 MISHNAH: THE CHALLENGE TO GOD Page 33 GEMARA : THE WORLD HAS A WAY OF ITS OWN Page 36 DOES CRIME PAY? Page 38 AGAINST MY DIVINE WILL Page 41 2 IV. MOSHE’S BIG QUESTION TO GOD: THE SCIENCE OF MORAL GENETICS AND THE EXPLANATION OF THE RIGHTEOUS WHO SUFFER TB Berachot 7a ) Page 44 ) צדיק ורע לו INTRODUCTORY EXERCISE: AN AUDIENCE WITH GOD (Shemot 33: 13-20) Page 45 MOSHE’S BIG QUESTION: WHY DO THE WICKED PROSPER? Page 47 WHY DO THE WICKED PROSPER? – FOUR ANSWERS Page 48 V. -

Maimonides on Teshuvah: the Ways of Repentance

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2017 Maimonides on Teshuvah: The Ways of Repentance Henry M. Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. M. (2017). Maimonides on Teshuvah: The Ways of Repentance. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maimonides on Teshuvah The Ways of Repentance Henry Abramson Fifth Edition 2017 תשע׳׳ז CreateSpace Edition License Notes Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute portions of this book for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided appropriate citation of the source, in accordance with the Talmudic dictum of Rabbi Elazar in the name of Rabbi Hanina (Megilah 15a): “anyone who cites a teaching in the name of its author brings redemption to the world.” Copyright 2017 Henry Abramson Version 5.0 Av 5777 (August 2017) Cover design by Bentsion Janashvili בס׳׳ד לאבי מורי יעקב דוד בן אליהו ע’’ה איש חסד ואמת To my father and teacher Jack David Abramson A Man of Compassion and Integrity 1928-2014 Other Works by Henry Abramson Jewish History A Prayer for the Government: -

Daf Ditty Yoma 3: Kivyachol a THEOLOGICAL PARADOX: DIVINE POWER and HUMAN INITIATIVE

Daf Ditty Yoma 3: Kivyachol A THEOLOGICAL PARADOX: DIVINE POWER AND HUMAN INITIATIVE 1 Peh, zayin, reish, kuf, shin, beit, an acronym for: Lottery [payis], as a new lottery is performed on that day to determine which priests will sacrifice the offerings that day, and the order established on Sukkot does not continue; the blessing of time [zeman]: Who has given us life, sustained us, and brought us to this time, is recited just as it is recited at the start of each Festival; Festival [regel], as it is considered a Festival in and of itself and there is no mitzva to reside in the sukka (see Tosafot); offering [korban], as the number of offerings sacrificed on the Eighth Day is not a continuation of the number offered on Sukkot but is part of a new calculation; song [shira], as the Psalms recited by the Levites as the offerings were sacrificed on the Eighth Day are not a continuation of those recited on Sukkot; blessing [berakha], as the addition to the third blessing of Grace after Meals and in the Amida prayer (see Tosafot) is phrased differently than the addition recited on Sukkot. RASHI 2 3 The Gemara challenges further: And say that the priest should be sequestered before the festival of Shavuot, which is a Festival preceded by weekdays, as there too it is a matter of sequestering of seven days for one day. Rabbi Abba said: There is a distinction between the inauguration and Shavuot, as one derives an instance where the obligatory offering is one bull and one ram, Yom Kippur, from an instance where the obligatory offering is one bull and one ram, the inauguration, to the exclusion of Shavuot, when they are two rams that are offered. -

Tosefta Berachot

Tosefta Berachot Translated into English with a commentary by Eliyahu Gurevich www.toseftaonline.org Vowelization of the Hebrew Text by Rabbi Levi Sudri www.levisudri.com Published by: Eliyahu Gurevich 848 N Rainbow Blvd. #1744 Las Vegas, NV 89107 USA Website: www.toseftaonline.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2010 by Eliyahu Gurevich 1st Edition All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-0-557-38968-1 Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-557-38985-8 Dedicated to my grandfather, Peter Tsypkin, who taught me how to build a bridge across the river and not along it. Посвящено моему деду, Петру Цыпкину, кто научил меня как строить мост поперёк реки, а не вдоль. Table of Contents Introduction to the Tosefta ................................................................................ 6 Who wrote the Tosefta? ................................................................................. 8 The order of the tractates of the Tosefta ....................................................... 9 Printed editions of the Tosefta ..................................................................... 22 Commentaries on the Tosefta ...................................................................... 24 Translations of the Tosefta ........................................................................... 29 Books about the Tosefta .............................................................................. -

Seder Zeraim in a Time of Isolation

A Resource for Learning Mishna Contents Introduction . 2 How to use this book. .2 Berachot (Blessings) . 3 Peah (Corners) .. .14 Demai (Food in doubt) . .22 Kilayim (Forbidden mixtures). 26 Shevi’it (Seventh year) . 30 Terumot (Donations). 36 Ma’asrot (Tithes) . 40 Ma’aser Sheni (Second tithe). .42 Challah (Bread donation) . .44 Orlah (Young trees) . .48 Bikkurim (First fruits). 50 Acknowledgments. .53 About this project. .54 Six reasons to learn Mishna . .55 Introduction This is a resource for anyone who wants to learn Jewish text and relate it to the world today. It goes book by book through the rst order of Mishna ( Seder Zeraim, or the Order of Seeds) and samples texts that may be especially relevant in a moment of communal crisis. The subject of Seder Zeraim , ostensibly, is agriculture and food production. Like all rabbinic literature, however, it meanders into many adjacent elds, frequently touching topics of gratitude and charity. At precisely a moment in history when those things feel fraught, hard, and more important than ever, I believe this seder is uniquely relevant to us today. How to use this book Each mishna is presented below in Hebrew and English, followed by a brief explanation, and concluding with reections or questions for further pondering. I suggest reading the text rst, in Hebrew or in English, and using the reection and question section as a jumping o point for your thoughts or discussions with a friend. The direct English translations lack important context that is needed to understand the mishna. The explanations below ll in those gaps and will make the mishna comprehensible.