A Study of the Redaction of the Babylonian Talmud As Reflected in Threesugyot of Tractate Eruvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September/October

A Traditional, Egalitarian and Participatory Conservative Synagogue ELUL 5777/TISHREI/HESHVAN 5778 NEWSLETTER/VOLUME 30:1 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 Or Zarua Annual Tshuvah Lecture Selihot Study with Rabbi Bolton Rabbinic Irreverence: Repentance and Forgiveness Imagining a Repentant God at the Time of the Spanish Expulsion: Rabbi Dov Weiss, PhD Abarbanel’s Take on Tshuvah Department of Religion University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Saturday, September 16 8:00 pm: Dessert Reception Sunday evening, September 24, 6:00 pm 8:30 pm: Selihot Study s we approach transgressing Torah law. Dr. Weiss (son with Rabbi Bolton the High Holy of Rabbi Avi Weiss) recently published a 9:30: pm Selihot Service Days, the process book, Pious Irreverence: Confronting God of repentance in Rabbinic Judaism, that ach Shabbat of 5777 we have Amust become our focus. explores these daring Egleaned from Don Yitzhak Abarbanel's As the High Holy Day Rabbinic texts. erudite commentary on the weekly Torah liturgy makes clear, our In this Tshuvah Lecture, portion. At Selihot, as we turn towards fate for the coming year Dr. Weiss will address why the new year, we will study selections may hinge on the efficacy some Rabbis envisioned a from the masterwork that address and of our tshuvah, which must involve genuine perfect God as performing explore repentance. This past year, while introspection, a thoroughgoing refinement tshuvah and what religious we have seen some of those passages as of character, and a deep commitment to values and insight might they arose in the context of our reading improvement in our conduct. Each year at Or be expressed in these radical texts. -

Our Very Life the Sukkah Helps the Jews Remember Their History and Their Covenant with God

TORAH FROM JTS www.jtsa.edu/torah A Jewish man remembers the sukkah in his grandfather’s home And the sukkah remembers for him The wandering in the desert that remembers The grace of youth and the tablets of the Ten Commandments Sukkot 5778 סוכות תשע"ח And the Golden Calf and the thirst and the hunger That remembers Egypt. Our Very Life The sukkah helps the Jews remember their history and their covenant with God. The image of the 19th century sukkah from the collection of the Paris Dr. Jason Rogoff, Academic Director of Israel Jewish Museum expresses this notion with its elaborate panels depicting not Programs, Assistant Professor of Talmud and only images of an Austrian village, the dwelling of the owner of the sukkah, Rabbinics, JTS but also a view of Jerusalem, the walls of the old city, and the Decalogue. One time it happened that a priest poured the libation on his I hope that this year you invite into your sukkah not only your friends and feet, and all the people pelted him with their etrogim. family but also those who are no longer with us yet remain part of our (M. Sukkah 4:9) memories of the past. The above Mishnah describes a scandalous episode set on the festival of Sukkot during the Second Temple period. The previous mishnah explains that on each day of the festival there was a ceremony where the priests would fill a golden flask with water from the Shiloah spring and bring it to the Temple to offer as a sacrifice on the altar. -

October 2020 Have Made Very Little Difference to Their Celebrations

KOL AMI Jewish Center & Federation New ideas of the Twin Tiers Congregation Kol Ami A different kind of Sukkot Jewish Community School When every Jewish household built a sukkah at home, a pandemic would October 2020 have made very little difference to their celebrations. Maybe fewer guests would have been invited for meals in the sukkah, and it might have been harder to obtain specialty fruits and vegetables, but the family had the suk- In this issue: kah and could eat meals in it, perhaps even sleep in it. Service Schedule 2 That is still widespread in Israel and in traditional communities here, but more of us rely on Sukkot events in the synagogue for our “sukkah time.” Torah/Haftarah & Candle Lighting 2 This year there won’t be a Sukkot dinner at Congregation Kol Ami and we Birthdays 4 won’t be together for kiddush in the sukkah on Shabbat (which is the first day of Sukkot this year). Mazal Tov 4 Nevertheless, Sukkot is Sukkot is Sukkot. It may be possible for you to CKA Donations 5 build a sukkah at home—an Internet search will find directions for building one quickly out of PVC pipe or other readily JCF Film Series 6 available materials. Sisterhood Opening Meeting 8 Even without a sukkah, we can celebrate the themes of Sukkot. In Biblical Israel it was a har- Jazzy Junque 8 vest festival, so maybe you can go to farm JCF Donations 8 stands and markets for seasonal produce. Baked squash is perfect for the cooler weather, Yahrzeits 9 cauliflower is at its peak—try roasting it—and In Memoriam 10 it’s definitely time for apple pie. -

Lulav on Shabbat

בס"ד Volume 8. Issue 35 Lulav on Shabbat The fourth perek lists the mitzvot performed during sukkot establishing Rosh Chodesh. The Tosfot Yom Tov stresses including the number of days that the mitzvah applies. The that the Gemara was referring to the times of the Beit first of these is the mitzvah of lulav; or more accurately the HaMikdash and that even though those people outside mitzvah of arbaat haminim (four species). According to Israel may have known how to calculate Rosh Chodesh, Torah law, the mitzvah of lulav is to be performed in the since they had to rely on it being fixed in Eretz Yisrael, Beit HaMikdash for the seven days of Sukkot (excluding they were considered as if they did not know. Such an Shimini Atzeret). Outside the Beit Hamikdash the mitzvah explanation however does not help the Bartenura due to to shake lulav was only for the first day. The Mishnah what appears to be an inconsistency between his however teaches that it is possible that the mitzvah would explanation here and his ruling regarding etrog stated apply in the Beit HaMikdash for either six or seven days of above.1 What then is our status nowadays with respect to sukkot depending on the year. If the first day of sukkot was establishing Rosh Chodesh? Shabbat, then the mitzvah was performed for seven days. If however the first day was not Shabbat, meaning that The Tosfot Yom Tov suggest that explanation of the Shabbat was on one of the remaining days of Sukkot, then Rambam should solve our difficulty whose ruling the the mitzvah was performed for six days with it not being Bartenura shares in the above two cases. -

KS 3 Talmud Page Layout Copy

Page Chapter name Tractate name Chapter number Ein mishpat, Ner mitzvah Rashi’s commentary –Rashi (an acronym for Rabbi (Hebrew: Well of justice, Lamp of Shlomo Yitchaki) was a major Jewish scholar active in the commandment) Compiled in 11th century France. Rashi compiled the first the 16th century this provides the complete commentary on the Talmud. The Mishnah source references to the laws are written in in a brief, terse style without being discussed on the page. punctuation and Rashi’s commentary is directed towards helping readers work through the text and understand its basic form and content. Tosafot (Hebrew: additions) These Mishnah and Gemara The central column of the page contains medieval commentaries were written in verses of the Mishnah followed by verses from the Gemara. the 12th and 13th centuries. They are the The Mishnah is the primary record of the teaching, decisions work of various Talmudic scholars and disputes of a group of Jewish religious and judicial scholars primarily living in France and Germany. known as Tannaim, active from about 10 to 220 CE. Originally transmitted orally, it was edited into its current form and written down in 200 CE by Rabbi Yehuda Hanasi. Written primarily in Hebrew, it is divided into 63 tractates and organized into six sections or ‘orders’. The Gemara is an analysis and expansion on the Mishnah. There are two versions - the Other commentaries Various other Babylonian Talmud (the most commonly studied) and the commentaries appear in the margins Jerusalem Talmud. The Gemara is written primarily in Aramaic of a printed Talmud page. -

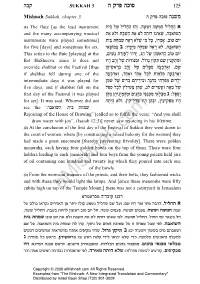

Mishnah Sukkah, Chapter 5 D Wxt Dkeq Dpyn

dkw SUKKAH 5 d wxt dkeq 125 Mishnah Sukkah, chapter 5 d wxt dkeq dpyn (1) The flute [as the lead instrument ziA¥ lW¤ lil¦g¨d¤ Edf¤ .dX¨W¦e§ dX¨n¦g£lilgd ¦ ¨ ¤ ` and the many accompanying musical z`¤Ÿ§¨©©¤Ÿ `le zAXd z` `l dgFC ¤ Fpi`W ¥¤,da`FXd ¨¥ © instruments were played sometimes] ziA¥zg©n§U¦ d`¨x¨`ŸNW¤in¦ lM¨,Exn§`¨.aFh mFi for five [days] and sometimes for six. i`vFnA¥¨ §a :einIn ¨¨¦ dgnU ¨§¦ d`x ¨¨Ÿ `l ,da`FXd ¨¥ © This refers to the flute [playing] at the ,miWp¦¨ zxfrl ©§¤§Ecxi §¨ ,bg © lW ¤ oFW`xd ¦¨ aFh mFi Bet HaShoeva, since it does not Eid¨ad¨f¨lW¤zFxFpn§E .lFcB¨oETY¦ mW¨oip¦T§z©n§E override shabbat or the Festival [thus od¤iW¥`x¨A§ ad¨f¨ lW¤ mil¦t¨q§ dr¨A¨x§`©e§ ,mW¨ if shabbat fell during one of the dr¨A¨x§`©e§ ,cg¨`¤e§ cg¨`¤ lk¨l§ zFnN¨qª dr¨A¨x§`©e§ intermediate days it was played for on¤W¤ lW¤ miC¦M© md¤ic¥ia¦E dP¨dªk§ ig¥x§R¦n¦ mic¦l¨i§ five days, and if shabbat fell on the lt¤q¥ lk¨l§ oil¦iH¦n© od¥W¤ ,bŸl mix¦U§r¤e§ d`¨n¥ lW¤ first day of the Festival it was played odn¤¥ odipindnE ¤¥¨§¤¥ mipdk ¦£Ÿiqpkn ¥§§¦ i`lAn ¥¨§¦b :ltqe ¤¥¨ for six]. It was said: Whoever did not dz¨i§d¨ `Ÿle§ ,oiw¦il¦c§n© Eid¨ od¤a¨E ,oir¦iw¦t§n© Eid¨ see the “da`eyd zia zgny — Rejoicing of the House of Drawing” [called so to fulfill the verse: “And you shall draw water with joy”, (Isaiah 12:3)] never saw rejoicing in his lifetime. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Rabbi Daniel Stein Halacha L’Maaseh Program Coordinator, RIETS

Sukkot on the Go? Traveling During Sukkot Rabbi Daniel Stein Halacha L’Maaseh Program Coordinator, RIETS For many families, yom tov in general and chol ha-moed specifically have become sacrosanct times for visiting family or for taking family excursions. However, traveling on Jewish holidays presents a variety of dilemmas. On Pesach, travelers must contend with what to eat on the road, while on sukkot they must contend with where to eat. Despite the recent innovations in sukkah technology, where to eat and sleep en route can still be worrisome. Our discussion will focus on the halachot pertaining to the traveler, and will address the following questions: • Are there any exceptions to the obligation to eat in a sukkah for the traveler? • If yes, why? Under what circumstances may they be utilized? • May one embark on a journey knowing that there will be no sukkah along the way? • Is there a difference between snacking versus eating a meal? The Traveling Exemption הולכי דרכים ביום פטורין מן הסוכה Those who travel by day are exempt from the sukkah by day, but are ביום וחייבין בלילה , הולכי דרכים obligated at night. Those who travel at night are exempt from the בלילה פטורין מן הסוכה בלילה, sukkah at night, but are obligated by day. Those who travel both by וחייבין ביום. הולכי דרכים ביום day and by night are exempt from the sukkah both by day and by ובלילה פטורין מן הסוכה בין ביום night. Those who are traveling for a mitzvah purpose are exempt ובין בלילה. הולכין לדבר מצוה from the sukkah both by day and by night, as was the case with R. -

Sukkot Potpourri

Sukkot Potpourri [note: This document was created from a selection of uncited study handouts and academic texts that were freely quoted and organized only for discussion purposes.] Byron Kolitz 30 September 2020; 12 Tishrei 5781 Midrash Tehillim 17, Part 5 - Why is Sukkot so soon after Yom Kippur? (Also referred to as Midrash Shocher Tov; its beginning words are from Proverbs 11:27. The work is known since the 11th century; it covers only Psalms 1-118.) In your right hand there are pleasures (Tehillim 16:11). What is meant by the word pleasures? Rabbi Abin taught, it refers to the myrtle, the palm-branch, and the willow which give pleasure. These are held in the right hand, for according to the rabbis, the festive wreath (lulav) should be held in the right hand, and the citron in the left. What kind of victory is meant in the phrase? As it appears in the Aramaic Bible: ‘the sweetness of the victory of your right hand’. That kind of victory is one in which the victor receives a wreath. For according to the custom of the world, when two charioteers race in the hippodrome, which of them receives a wreath? The victor. On Rosh Hashanah all the people of the world come forth like contestants on parade and pass before G-d; the children of Israel among all the people of the world also pass before Him. Then, the guardian angels of the nations of the world declare: ‘We were victorious, and in the judgment will be found righteous.’ But actually no one knows who was victorious, whether the children of Israel or the nations of the world were victorious. -

Sukkot in the Torah דַּבֵּ ר אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל

BY RABBI ELAZAR MEISELS “For seven days you shall dwell in Sukkot… This is so that future generations will know Sukkot in the Torah that I had the Israelites live in booths when I brought them out of Egypt.” ּדַ ּבֵר ֶאל ּבְנֵי יִ ְש ׂרָ ֵאל לֵ ֹאמר ּ ַב ֲח ִמ ּׁ ָשה עָ ָש ׂר יוֹם לַ ֹחדֶשׁ ַה ּׁ ְש ִב ִיעי ַה ּזֶה ַחג ַה ּסֻכּוֹת Rabbi Eliezer holds that these booths were the Clouds of Glory which encircled ׁ ִשבְעַת יָ ִמים לַ ֹידוָד: ּ ַביּוֹם ָהרִאשׁוֹן ִמ ְקרָא ֹקדֶשׁ ּכָל ְמלֶאכֶת עֲ ֹבדָה ֹלא ַתעֲשׂוּ: and protected us throughout our stay in ׁ ִשבְעַת יָ ִמים ּ ַת ְקרִיבוּ ִא ּׁ ֶשה לַ ֹידוָד ּ ַביּוֹם ַה ּׁ ְש ִמינִי ִמ ְקרָא ֹקדֶשׁ יִ ְהיֶה לָכֶם the desert. Rabbi Akiva explains that the verse refers to the actual tents in which וְ ִה ְקרַבְ ּ ֶתם ִא ּׁ ֶשה לַ ֹידוָד עֲצֶרֶת ִהוא ּכָל ְמלֶאכֶת עֲ ֹבדָה ֹלא ַתעֲשׂוּ: ֵא ּלֶה מוֹעֲדֵי .we lived while sojourning the desert יְ ֹדוָד ֲא ׁ ֶשר ּ ִת ְקרְאוּ ֹא ָתם ִמ ְקרָ ֵאי ֹקדֶשׁ לְ ַה ְקרִיב ִא ׁ ֶשּה לַ ֹידוָד ֹעלָה ִוּמנְ ָחה זֶ ַבח Talmud, Tractate Sukkah 11b וּנְ ָס ִכים ּדְ ַבר יוֹם ּבְיוֹמוֹ: ִמ ּלְ ַבד ׁ ַש ּבְ ֹתת יְ ֹדוָד ִוּמ ּלְ ַבד ַמ ּ ְת ֵנוֹתיכֶם ִוּמ ּלְ ַבד ּכָל What is the significance of the tents נִדְרֵיכֶם ִוּמ ּלְ ַבד ּכָל נִדְ ֹב ֵתיכֶם ֲא ׁ ֶשר ּ ִת ּ ְתנוּ לַ ֹידוָד: ַאךְ ּ ַב ֲח ִמ ּׁ ָשה עָ ָש ׂר יוֹם לַ ֹחדֶשׁ in the desert that they deserve such a serious commemoration? The Sukkah ַה ּׁ ְש ִב ִיעי ּבְ ָא ְס ּפְכֶם ֶאת ּ ְת ַבוּאת ָה ָארֶץ ּ ָת ֹחגּוּ ֶאת ַחג יְ ֹדוָד ׁ ִשבְעַת יָ ִמים ּ ַביּוֹם reminds us of the great faith of the Jewish ָהרִאשׁוֹן ׁ -

The Missing 168 Years - Part 1 Ou Israel Center - Winter 2019

5779 - bpipn mdxa` [email protected] 1 c‡qa HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 117 - THE MISSING 168 YEARS - PART 1 OU ISRAEL CENTER - WINTER 2019 A] TRADITIONAL JEWISH CHRONOLOGY - SEDER OLAM (S.O.) A1] EXILE AND REBUILDING d«G¤d© mŸewO¨d©Îl`¤ mk¤½ z§ `¤ aiW´¦ d¨l§ aŸeH½ d© ix´¦a¨C§Îz`¤ Æmk¤i¥l£r i³z¦ Ÿnw¦ d£e© m®k¤z§ `¤ cŸw´t§ `¤ d¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ l²a¤a¨l§ z`Ÿ¯ln§ itº¦ l§ iM¦Â 'd x´n©`¨ ÆdŸkÎiM«¦ 1. i:hk edinxi Yirmiyahu prophecies that the exile in Bavel will last 70 years before the people are brought back to Eretz Yisrael. mix®¦t¨Q§ A© iz¦ ŸpiA¦ l`¥I½p¦C«¨ Æip¦`£ Ÿek½ l§ n¨l§ Æzg©`© z³p©W§ A¦ :miC«¦U§ M© zEk¬ l§ n© lr© K©l½ n§ d¨ x´W¤ `£ i®c¨n¨ rx©´G¤n¦ WŸexe¥W§ g©`£ÎoA¤ W¤e²¨ix§c¨l§ zgÀ©`© z´p©W§ A¦ 2. d«¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ m©l¦ W¨ Exi§ zŸea¬ x§g¨l§ ze`Ÿ²Nn©l§ `ia½¦ ¨Pd© d´¨in¦ x§i¦Îl`¤ 'dÎxa©c§ d³¨id¨ xW¸¤ `£ mipÀ¦X¨ d© x´R©q§ n¦ a-`:h l`ipc Daniel, immersed in the exile in Bavel in the first year of the reign of Darius, son of Achashverosh, also understands from his reading of Nach that the exile should only last 70 years. d«¨pW¨ mir¬¦a§ W¦ df¤ dY¨n§ r©½ f¨ x´W¤ `£ d®c¨Edi§ i´x¥r¨ z`¥e§ m¦©l½ W¨ Exi§Îz`¤ m´g¥x©z§ Î`Ÿl« ÆdY¨`© iz©À n¨Îcr© zŸe`½ a¨v§ 'd x¼n©`ŸIe© 'dÎK`©l§ n© or©´I©e© 3. -

The Sea of Talmud: a Brief and Personal Introduction

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2012 The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry M. Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. M. (2012). The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEA OF TALMUD A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry Abramson Published by Parnoseh Books at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Henry Abramson Cover photograph by Steven Mills. No Talmud volumes were harmed during the photo shoot for this book. Smashwords Edition, License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment and information only. This ebook should not be re-sold to others. Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute this ebook for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided the book remains in its complete original form. Version 3.1 June 18, 2012. To my students All who thirst--come to the waters Isaiah 55:1 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One: Our Talmud Chapter Two: What, Exactly, is the Talmud? Chapter Three: The Content of the Talmud Chapter Four: Toward the Digital Talmud Chapter Five: “Go Study” For Further Reading Acknowledgments About the Author Introduction The Yeshiva administration must have put considerable thought into the wording of the hand- lettered sign posted outside the cafeteria.