Aligning with Both the Soviet Union and with the Pharmaceutical Transnationals: Dilemmas Attendant on Initiating Drug Production in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVERNMENT of INDIA LAW COMMISSION of INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI Vis-À-Vis RIGHT to INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 April, 2018 i ii Report No. 275 LEGAL FRAMEWORK: BCCI vis-à-vis RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT, 2005 Table of Contents Chapters Title Pages I Background 1-23 A. A Brief History of Cricket in India 1 B. History of BCCI 3 C. Evolution of the Right to Information 5 (RTI) in India (a) Right to Information Laws in 9 States 1) Tamil Nadu 9 2) Goa 10 3) Madhya Pradesh 12 4) Rajasthan 13 5) Karnataka 14 6) Maharashtra 15 7) Delhi 16 8) Uttar Pradesh 17 9) Jammu & Kashmir 17 10) Assam 18 (b) RTI Movement – social and 19 national milieu II Reference to Commission and Reports 24-30 of Various Committees A. NCRWC Report, 2002 24 B. 179th Report of the Law Commission 26 of India, 2001 C. Report of the Pranab Mukherjee 26 Committee, 2001 D. Report of the Working Group for 27 Drafting of the National Sports Development Bill 2013 E. Lodha Committee Report, 2016 28 iii III Concept of State under Article 12 of the 31-36 Constitution of India - Analysis of the term ‘Other authorities’ IV RTI – Human Rights Perspective 37-55 a. Right to Information as a Human 38 Right - Constitutional position 40 b. Application to Private Entities 44 (i) State Responsibility 45 (ii) Duties of Private Bodies 46 c. Human Rights and Sports 48 V Perusal of the terms “Public Authority” 56-82 and “Public Functions” and “Substantially financed” 1. -

Linde Form IEPF-1

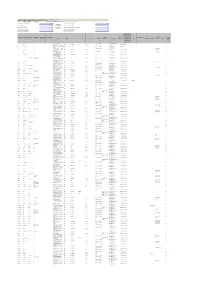

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the amount credited to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-1 CIN/BCIN L40200WB1935PLC008184 Prefill Company/Bank Name LINDE INDIA LIMITED Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 658007.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Validate Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Clear Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Sum of Other Investment Types 0.00 Date of event (date of declaration of dividend/redemption date Is the of preference shares/date Date of Birth(DD-MON- Investment Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount of maturity of Joint Holder Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type PAN YYYY) Aadhar Number Nominee Name Remarks (amount / Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred bonds/debentures/applic Name shares )under ation money any litigation. refundable/interest thereon (DD-MON-YYYY) 19 B B CHATERJEE ROAD LIND0000000002239 Amount for unclaimed and A BOSE NA INDIA West Bengal 700042 600.00 23-May-2014 No CALCUTTA 072 unpaid dividend CHLORIDE INDIA LIMITED EXIDE LIND0000000000403 Amount for unclaimed and A DASGUPTA NA HOUSE -

ALIGNING with BOTH the SOVIET UNION and with the PHARMACEUTICAL TRANSNATIONALS Dilemmas Attendant on Initiating Drug Production in India

Working Paper No: 2010/08 About the ISID The Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID), successor to the Corporate Studies Group (CSG), is a national-level policy research organization in the public domain and is affiliated to the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR). Developing on the initial strength of studying India’s industrial regulations, ISID has gained varied expertise in the analysis of the issues thrown up by the changing policy environment. The Institute’s research and academic activities are organized under the following broad thematic areas: Industrial Development: Complementarity and performance of different sectors (public, private, FDI, cooperative, SMEs, etc.); trends, structures and performance of Indian industries in the context of globalisation; locational aspects of industry in the context of balanced regional development. Corporate Sector: Ownership structures; finance; mergers and acquisitions; efficacy of regulatory ALIGNING WITH BOTH THE SOVIET UNION systems and other means of policy intervention; trends and changes in the Indian corporate sector in the background of global developments in corporate governance, integration and AND WITH THE PHARMACEUTICAL competitiveness. TRANSNATIONALS Trade, Investment and Technology: Trade policy reforms, WTO, composition and direction of trade, import intensity of exports, regional and bilateral trade, foreign investment, technology Dilemmas attendant on initiating imports, R&D and patents. Drug Production in India Employment, Labour and Social Sector: Growth and structure of employment; impact of economic reforms and globalisation; trade and employment, labour regulation, social protection, health, education, etc. Media Studies: Use of modern multimedia techniques for effective, wider and focused dissemination of social science research and promote public debates. -

Speech of the President

SPEECH BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, SHRI PRANAB MUKHERJEE AT THE INAUGURATION OF THE 66TH ANNUAL SESSION OF INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERS Mumbai, Maharashtra: 27-12-2013 1. It is indeed a privilege for me to present amidst you in this Sixty-Sixth Indian Chemical Engineering Congress and its inaugural session. This is the Annual Session of the Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers (IICE). At the outset, let me extend a warm welcome to the eminent academicians from abroad, who have come to India to participate in this prestigious event. I also accord my best wishes to the distinguished personalities from the Indian academia and industry who have gathered in this forum. Ladies and Gentlemen: 2. IICE is a prominent body of professionals from industry, academics and research. It provides a platform for professional excellence and continuous education in chemical engineering. I am happy that for this year‟s Congress, this organization has associated itself with the Institute of Chemical Technology (ICT) which completed eight decades of fruitful existence on first October, this year. 3. ICT was founded by the University of Mumbai as the Department of Chemical Technology. It was converted into an Institute in 2002 and was granted full autonomy in 2004. It was given Deemed University Status in 2008. ICT has nurtured innumerable chemical engineers and scientists, many of whom have gone on to become heads of national level research institutions and scientific regulatory bodies, and first rate entrepreneurs. Late Manubhai Shah, Union Cabinet Minister for Industries and Commerce in the late fifties and early sixties, was also a student of this prestigious institution. -

Caprihans India Limited Kycdata List

Sr No of BANK MOBILE No FOLIONO NAME JOINTHOLDER1 JOINTHOLDER2 JOINTHOLDER3 ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 CITY PINCODE Shares SIGNATURE PAN1 DETAILS NO EMAIL NOMINATION DIPTIKA SURESHCHANDRA RAGINI C/O SHIRISH I NEAR RAMJI 1 'D00824 BHATT SURESHCHANDRA TRIVEDI PANCH HATADIA MANDIR,BALASINOR 0 0 35 REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED CHHOTABHAI BIDI JETHABHAI PATEL MANUFACTURES,M.G.RO 2 'D01065 DAKSHA D.PATEL & CO. AD POST SAUGOR CITY 0 0 40 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED DEVIPRASAD DAHYABHAI BATUK DEVIPRASAD 1597 3 'D01137 SHUKLA SHUKLA SHRIRAMJINISHERI KHADIA AHMEDABAD 1 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ANGODD MAPUSA 4 'E00112 EMIDIO DE SOUZA VINCENT D SOUZA MAPUSA CABIN BARDEZ GOA 0 0 70 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 5 'R02772 RAMESH DEVIDAS POTDAR JAYSHREE RAMESH POTDAR GARDEN RAJA PETH AMRAVATI P O 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED SHASTRI GANESH BLOCK NO A‐ AMARKALAPATARU CO‐ NAGAR,DOMBIVALI 6 'A02130 ASHOK GANESH JOSHI VISHWANATH JOSHI 6/2ND FLOOR OP HSG SOCIETY WEST, 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI CHIMANLAL NEAR MADHU PURA, 7 'A02201 PATEL DUDHILI NI DESH VALGE PARAMA UNJHA N.G. 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI BHAILALBHAI A‐3 /104 ANMOL OPP NARANPURA NARANPURA 8 'A03187 PATEL TOWER TELEPHONE EXCHANGE SHANTINAGAR AHMEDABAD 0 0 140 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED MIG TENAMENT PREMLATA SURESHCHANDRA NO 8 GUJARAT GANDHINAGAR 9 'P01152 PATEL HSG BOARD SECT 27 GUJARAT 0 0 77 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED C/O M M SHAH, 10 'P01271 PIYUSHKUMAR SHAH MANUBHAI SHAH BLOCK NO 1, SEROGRAM SOCIETY, NIZAMPURA, BARODA 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 169 THAPAR 11 'P02035 PREM NATH JAIN NAGAR MEERUT 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 92/6 MITRA PARA DT. -

General Elections, 1957 to the Second Lok Sabha

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1957 TO THE SECOND LOK SABHA VOLUME I (NATIONAL AND STATE ABSTRACTS & DETAILED RESULTS) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India - General Election, 1957 ( 2nd LOK SABHA) STATISTICAL REPORT – Volume I ( National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results ) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page no. Part - I 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviation 1 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 2 3. Seats and Constituencies 4. Size of Electorate 3 5. Voter Turnout and Polling Stations 4 6. Number of Candidates per Constituency 5 7. Number of Candidates and Forfeiture of Deposits 6 8. List of Successful Candidates 7 - 28 9. Performance of National Parties vis-à-vis Others 29 10. Seats won by Parties in States / U.T.s 30 - 32 11. Seats won in States / U.T.s by Parties 33 - 35 12. Votes Polled by Parties – National Summary 36 13. Votes Polled by Parties in States / U.T.s 37 - 40 14. Votes Polled in States / U.T.s by Parties 41 - 44 15. Performance of Women Candidates 45 16. Performance of Women Candidates in National Parties vis-à-vis Others 46 17. Women Candidates 47 - 50 Part - II 18. Detailed Results 51- 108 Election Commission of India-General Elections,1957 (2nd LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJS ALL INDIA BHARTIYA JAN SANGH 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 4 . PSP PRAJA SOCIALIST PARTY OTHER STATE PARTIES 5 . CNSPJP JANATA 6 . FBM FORWARD BLOC (MARXIST) 7 . GP GANATANTRA PARISHAD 8 . -

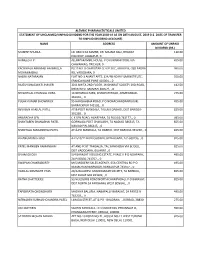

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00 -

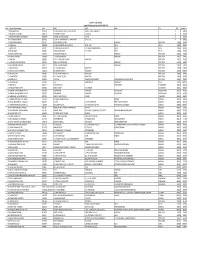

Sr.No. Name of Shareholders Folio Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN Amount 1

Cummins India Limited Unpaid Dividend data for the Final 2018-2019 Sr.No. Name of Shareholders Folio Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN Amount 1 RAM SARAN SAHU R003559 CENTRAL RAILWAY SR ELEC ENGR 2ND FLR PARCEL OFFICE BOMBAY V T 0 0 92400 2 MAHADEOLALL KAJARIA M001141 22 BONFIELD S LANE CALCUTTA 0 0 92400 3 MANOHAR KRISHNA PANANDIKAR M002970 YASHODHAN SHIVAJI ROAD THANA 0 0 46200 4 STATE BANK OF INDIA B090828 SECURITIES DEPARTMENT 1 STRAND ROAD CALCUTTA 0 0 58800 5 SAROOP NATH MUBAYI S001401 D/194 DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110003 92400 6 MUNSHILAL M005545 C/O M/S MANOHARLAL MUNSHILAL KHARI BAOLI DELHI DELHI 110006 92400 7 SHANTI DEVI S003081 C/O M/S REGAL ELECTRIC CO 3152 BAZAR TURKAMAN GALI DELHI DELHI 110006 46200 8 PRITAM KAUR P008537 6, BOULEVARD ROAD CIVIL LINES DELHI DELHI 110006 31500 9 SHOBHA DEEPAK SINGH S010770 W 81 GREATER KAILASH NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110014 75600 10 HAKUMAT RAI PURI H000049 J 112 RAJOURI GARDEN NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110015 92400 11 GIAN DEVI G000801 B-121, F F SARVOYA ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110017 92400 12 LILARAM T KARAMCHANDANI L001350 2ND/A-70 LAJPAT NAGAR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 63000 13 SARLA KARAMCHANDANI S001070 2ND/A-70 LAJPAT NAGAR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 63000 14 SONIA KAPOOR S043520 B-41 KAILASH COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110048 42000 15 GURBAKSH KAUR DHARIWAL G004458 B-I GREATER KAILASH-I NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110048 197400 16 SHIV BIR SINGH S004206 M-185, GREATER KAILASH-II, NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110048 92400 17 VEENA KAPOOR V000929 B-41, KAILASH COLONY, NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110048 50400 18 -

Lok Sabha Debates

Third Series1R.63 Friday, May 1, 1964 Vaisakha 11, 1886 (Saka) /2.6$%+$ '(%$7(6 Seventh Session (Third/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 New Delhi CONTENTS No. 63-Friday, May 1, 1964/VaisaMha II, 1886 (SaMa) COLUMNS Oral Answers to Questions- *Starred Questions Nos. 1273 to 1275,1277 to 1280, 1282, 1283. 1286A, 1287, 1288 and 1290 13791-827 Short Notice Question No. 22 13827-31 Written Answers to Questions- Starred Questions Nos. 1276, 1281, 1285, 1289 and 1291 13831-35 Unstarred· Questions Nos. 2747 to 2759, 2761 to 2783, 2783A, 2783B, and 2783C . 13835-57 Correction of answer to U.S.Q. No. 1825 dated 3-4-1964 re. Small Scale Industries Corporation, Orissa. 13857 Calling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance- Bomb explosion in Poonch Power House 13857-59 Papers laid on the Table . 13859-61 Messages from Rajya Sabha 13861~2 Presentation of petition 13862 Business of the House and announcement rc: next session of Lok Sabha . 13862-75 Statement rc: Bokharo Steel Project- Shri C. Subramaniam 13875--'78 Coir Industry (Amendment) Bill- Motion to consider 13878-905 Shri Maniyangadan 13887-82 Shri N. Sreekantan Nair 13882- 87 Shri B. K. Das 1388 7--88 Shri Yashpal Singh 13888-90 Shri S. C. Samanta 13890-92 Dr. Sarojini Mahishi 13892- 06 Dr. M. S. Aney . 13896--97 Shri ~anubhai Shah 13897---904 Clauses 2 to 7 and 1 . 13904-05 ~otion to pass as amended Shri Manubhai Shah 1390 5 *The sign +marked above the name ofa Member indicates that the question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that ~ember. -

Meghji-Pethraj-Shah-His-Life-Achievements-By-Paul-Marett.Pdf

MEGHJI PETHRAJ SHAH His Life and Achievements by Paul Marett The unique qualities of your character and ideals will remain our treasured inheritance. MEGHJI PETHRAJ SHAH His Life and Achievements by Paul Marett Based on an original Gujarati biography by Tarak Mehta (1975) Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Bombay and London 1988 Published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, London. © Paul Marett 1988. CONTENTS Explanatory Note xi Acknowledgements xii Preface by Shri Uchhrangarai N. Dhebar xiii CHAPTER I Early Life: India 1904-1919 1 CHAPTER II East Africa - Early Years: 1919-1930 11 CHAPTER III Expansion and Prosperity 21 CHAPTER IV Family Life and Further Expansion 37 CHAPTER V Retirement and Establishment of the M.P. Shah Trust 49 CHAPTER VI More Reminiscences 71 CHAPTER VII Further Charitable Donations 77 CHAPTER VIII Personality 85 CHAPTER IX The Philanthropist 93 CHAPTER X The London Years 101 EPILOGUE 117 APPENDIX List of Donations 128 MAPS Kenya 131 Gujarat 132 UPDATED PHOTOS 134 INDEX 139 v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Meghji Pethraj Shah Frontispiece Dabasang xvi Premchandbhai and Meghjibhai 22 Opening of the Thika factory, April 1934 29 Reception at the opening of the Thika factory 31 Inside the Thika factory 1934 35 Meghjibhai, c. 1935 39 Meghjibhai's home in Thika 43 Meghjibhai, Premchandbhai, Hemrajbhai and Juthalalbhai 44 Meghjibhai's bust at the Medical College, Jamnagar 48 M. P. Shah Hospital, Nairobi 52 Vipin, Khetshibhai, Jaya, President Jomo Kenyatta and Hemrajbhai 56 M. P. Shah Medical College, Jamnagar 63 M. P. Shah Leprosy Sanatorium 67 Maniben M. P. Shah Mahila Ashray Griha 69 Visit of Pandit Nehru to Meghjibhai's home 76 M. -

Induction Material for OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Department of Commerce Induction Material FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY INDUCTION MATERIAL MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE November 2020 1 Induction Material I N D E X Particulars Page No. * Statement showing Ministers in the Department of Commerce since 1947 5-8 * Statement showing Secretaries in the Ministry of Commerce 9 * Work allocation 10-13 * Organisational set-up 14 * Brief history of Ministry of Commerce 15-18 * List of Offices under Department of Commerce 19-22 1. Logistics Division 23-24 2. Trade Policy Division [TPD] 25-26 2. Regional & Multilateral Trade Relations [RMTR] 27-28 3. Directorate General of Trade Remedies [DGTR] 29-31 4. Economic & Social Commission for Asia & Pacific [ESCAP] 32-33 5. Foreign Trade Territorial Division - FT(AF) 34-35 - FT(NAFTA) 36 - FT(LAC) 37-39 - FT(Europe) 42-43 - FT(CIS) 44 - FT(WANA) 45-46 - FT(Oceania) 47 - FT(ASEAN) 48 - FT(NEA) 49 - FT(SA) 50 6. Foreign Trade (Coordination) 51-52 7. Technical Assistance / Trade Commissioner [TA/TC] 53-54 8. Foreign Trade (Minerals & Ores) [FT(M&O)] 55 9. Foreign Trade (State Trading) [FT(ST)] 56 10. Trade Promotion [TP] 57 2 Induction Material 11. Export Inspection [EI] 58 12. Export Promotion (Agriculture) [EP(Agri)] 59-60 13. Export Promotion (Marine Products) [EP(MP)] 62 14. Export Promotion (Leather & Sports Goods) [EP(LSG)] 63 15. Export Promotion (Gems & Jewellery) [EP(G&J)] 64 16. Export Promotion (Engineering) 65 17. Export Promotion (Electronics & Computer Software) [EP(E&SW)] 66 18. Export Promotion (Chemicals & Allied Products) [EP(CAP)] 67-68 19. -

![[ 24 AUG. 1962 ] to Questions 3H2 Tithe PRIME MINISTER ANI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5104/24-aug-1962-to-questions-3h2-tithe-prime-minister-ani-5145104.webp)

[ 24 AUG. 1962 ] to Questions 3H2 Tithe PRIME MINISTER ANI

3111 Written Answers [ 24 AUG. 1962 ] to Questions 3H2 THE MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (SHRI MANUBHAI SHAH): Yes, Sir. There is 2 general shortage of copper due to the difficult foreign exchange situation. More quota can be given only when the foreign exchange position improves. 684. [Transferred to the 30th August, 1962.] STEEL QUOTAS FOR SMALL-SCALE AND STEEL PROCESSING INDUSTRIES 685. SHRI V. M. CHORDIA: Will the tITHE PRIME MINISTER ANI MINISTER Minister of COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY be OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (SHRI pleased to state: JAWAHARLAL NEHRU) : (a) Sc far 26 (a) the quota of indigenous steel motorable, jeepable and bridle roads have (category-wise) allotted to small- been under construction under the General scale industries and steel processing Aid Programme of India for the development industries during 1960-61 and 1961-62 of Sikkim. Out of this, construction on eight in various States; roads has been completed. The rest of them are in various stages of construction. The total (b) what was the actual supply of expenditure incurred so far on the the steel material against the quota construction of these roads (up to financial allotted for the above two years; and year 1961-62) is Rs. 1,61,90,316. (c) what steps Government propose to take to improve the supply posi (b) Under the Second Five Year Plan of tion? Sikkim, which will last till 1966 (and which coincides with the Third Five Year Plan of THE MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL India) 25 more roads would be constructed. A TRADE IN THE MINISTRY OF total outlay of approximately rupees three COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY (SHRI crores for road works has been provided in MANUBHAI SHAH): (a) to (c) A statement is Sikkim's Second Plan.