The Making of Swedish Working-Class Literature Magnus Nilsson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Staffan Björks Bibliografi

Staffan Björcks bibliografi 1937-1995 Rydén, Per 2005 Document Version: Förlagets slutgiltiga version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rydén, P. (Red.) (2005). Staffan Björcks bibliografi: 1937-1995. (Absalon; Vol. 22). Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen, Lunds universitet. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Staffan Björcks Bibliografi 1937–1995 sammanställd av Per Rydén ABSALON Skrifter utgivna vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Lund Staffan Björcks Bibliografi 1937–1995 sammanställd av Per Rydén Tryckningen av -

Swedish Literature on the British Market 1998-2013: a Systemic

Swedish Literature on the British Market 1998-2013: A Systemic Approach Agnes Broomé A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UCL Department of Scandinavian Studies School of European Languages, Culture and Society September 2014 2 I, Agnes Broomé, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. …............................................................................... 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the role and function of contemporary Swedish fiction in English translation on the British book market in the period 1998-2013. Drawing on Bourdieu’s Field Theory, Even Zohar’s Polysystem Theory and DeLanda’s Assemblage Theory, it constructs a model capable of dynamically describing the life cycle of border-crossing books, from selection and production to marketing, sales and reception. This life cycle is driven and shaped by individual position-takings of book market actants, and by their complex interaction and continual evolution. The thesis thus develops an understanding of the book market and its actants that deliberately resists static or linear perspectives, acknowledging the centrality of complex interaction and dynamic development to the analysis of publishing histories of translated books. The theoretical component is complemented by case studies offering empirical insight into the model’s application. Each case study illuminates the theory from a different angle, creating thereby a composite picture of the complex, essentially unmappable processes that underlie the logic of the book market. The first takes as its subject the British publishing history of crime writer Liza Marklund, as well as its wider context, the Scandinavian crime boom. -

Ref. # Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords 6437 Cg Kristen Liv En Bro Til Alle Folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981

Lang. Section Title Author Date Loaned Keywords Ref. # 6437 cg Kristen liv En bro til alle folk Dahl, Øyvind 1981 ><'14/11/19 D Dansk Mens England sov Churchill, Winston S. 1939 Arms and the 3725 Covenant D Dansk Gourmet fra hummer a la carte til æg med Lademann, Rigor Bagger 1978 om god vin og 4475 kaviar (oversat og bearbejdet af) festlig mad 7059 E Art Swedish Silver Andrén, Erik 1950 5221 E Art Norwegian Painting: A Survey Askeland, Jan 1971 ><'06/10/21 E Art Utvald att leva Asker, Randi 1976 7289 11211 E Art Rose-painting in Norway Asker, Randi 1965 9033 E Art Fragments The Art of LLoyd Herfindahl Aurora University 1994 E Art Carl Michael Bellman, The life and songs of Austin, Britten 1967 9318 6698 E Art Stave Church Paintings Blindheim, Martin 1965 7749 E Art Folk dances of Scand Duggan, Anne Schley et al 1948 9293 E Art Art in Sweden Engblom, Sören 1999 contemporary E Art Treasures of early Sweden Gidlunds Statens historiska klenoder ur 9281 museum äldre svensk historia 5964 E Art Another light Granath, Olle 1982 9468 E Art Joe Hills Sånger Kokk, Enn (redaktør) 1980 7290 E Art Carl Larsson's Home Larsson, Carl 1978 >'04/09/24 E Art Norwegian Rosemaling Miller, Margaret M. and 1974 >'07/12/18 7363 Sigmund Aarseth E Art Ancient Norwegian Design Museum of National 1961 ><'14/04/19 10658 Antiquities, Oslo E Art Norwegian folk art Nelson, Marion, Editor 1995 the migration of 9822 a tradition E Art Döderhultarn Qvist, Sif 1981? ><'15/07/15 9317 10181 E Art The Norwegian crown regalia risåsen, Geir Thomas 2006 9823 E Art Edvard Munck - Landscapes of the mind Sohlberg, Harald 1995 7060 E Art Swedish Glass Steenberg, Elisa 1950 E Art Folk Arts of Norway Stewart, Janice S. -

Inlelevhandledn A

margareta lindbom Svenska A •Svenska A • Elevhandledning • för Handbok i svenska språket Den levande litteraturen Levande texter Almqvist & Wiksell © Liber AB Redaktion: Kristina Lönn, Marie Carlsson Form: Ingmar Rudman Andra upplagan Liber AB, 113 98 Stockholm tfn 08-690 92 00 www.liber.se kundtjänst tfn 08-690 93 30, fax 08-690 93 01, e-post: [email protected] innehåll Svenska A på egen hand Information till handledaren 5 Studieenhet 1 7 Skolverkets kursplan och betygskriterier 7 Uppläggning av kursen 8 Läromedel 8 Diagnos 9 Moment I: Planering 9 Moment II: Studieteknik 9 Moment III: Studietips 10 Studieenhet 2 11 Moment I: Talandets ABC 11 Moment II: Biblioteket 11 Moment III: Informationssökning på nätet 12 Moment IV: Skiljetecken, förkortningar och sammansatta ord 13 Moment V: Stavning 14 Studieenhet 3 16 Moment I: Textanalys 16 Moment II: Boktips 17 Moment III: Person- och miljöskildring 18 Studieenhet 4 20 Moment I: Talspråk och skriftspråk 20 Moment II: Språkriktighet 20 Moment III: Att rätta sin text 21 Moment IV: Lästema 21 Studieenhet 5 25 Moment I: Berättelse 25 Moment II: Högläsning 26 Moment III: Ordklasser 26 Moment IV: Romanläsning 26 Moment V: Lyrikläsning 27 Moment VI: Loggboken 29 Lindbom: Svenska A Elevhandledning © Liber AB. A Elevhandledning Lindbom: Svenska 3 Studieenhet 6 30 Moment I: Redovisning av roman 30 Moment II: Muntlig framställning 30 Moment III: Referat 31 Studieenhet 7 33 Moment I: Textläsning 33 Moment II: Satsdelar 34 Moment III: Utredande uppsats 34 Moment IV: Romanläsning 35 Studieenhet 8 38 Moment I: Recension av roman 38 Moment II: Tema visor och vislyrik – från Bellman till Lundell 39 Moment III: Uppföljning av kursen 41 Moment IV: Loggboken 42 Avslutning av kursen 42 Rättstavningsprov 43 Förslag till sluttentamen på A-kursen 44 Ursvenska – distanskurs i gymnasiesvenska 45 Lindbom: Svenska A Elevhandledning © Liber AB. -

Martinson Nomadism.Pdf

due punti •• 52 © 2017, Pagina soc. coop., Bari Le avanguardie dei Paesi nordici nel contesto europeo del primo Novecento The Nordic Avant-gardes in the European Context of the Early 20th Century Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Roma, 22-24 ottobre 2015 a cura di / edited by Anna Maria Segala, Paolo Marelli, Davide Finco Per informazioni sulle opere pubblicate e in programma rivolgersi a: Edizioni di Pagina via dei Mille 205 - 70126 Bari tel. e fax 080 5586585 http://www.paginasc.it e-mail: [email protected] facebook account http://www.facebook.com/edizionidipagina twitter account http://twitter.com/EdizioniPagina Le avanguardie dei Paesi nordici nel contesto europeo del primo Novecento The Nordic Avant-gardes in the European Context of the Early 20th Century Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Roma, 22-24 ottobre 2015 a cura di / edited by Anna Maria Segala, Paolo Marelli, Davide Finco È vietata la riproduzione, con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, compresa la fotocopia. Per la legge italiana la fotocopia è lecita solo per uso personale purché non danneggi l’autore. Quindi ogni fotocopia che eviti l’acquisto di un libro è illecita e minaccia la sopravvivenza di un modo di trasmettere la conoscenza. Chi fotocopia un libro, chi mette a disposizione i mezzi per fotocopiare, chi favorisce questa pratica commette un furto e opera ai danni della cultura. Finito di stampare nell’ottobre 2017 dalle Arti Grafiche Favia s.r.l. - Modugno (Bari) per conto di Pagina soc. coop. ISBN 978-88-7470-580-1 ISSN 1973-9745 Contents Anna Maria Segala, Paolo Marelli, Davide Finco Preface 9 Anna Maria Segala The Dialectic Position of the Nordic Avant-gardes 11 SECTION 1 The Precursors Björn Meidal Strindberg and 20th Century Avant-garde Drama and Theatre 25 Kari J. -

Boklista 1949–2019

Boklista 1949–2019 Såhär säger vår medlem som har sammanställt listan: ”Det här är en lista över böcker som har getts ut under min livstid och som finns hemma i min och makens bokhyllor. Visst förbehåll för att utgivningsåren inte är helt korrekt, men jag har verkligen försökt skilja på utgivningsår, nyutgivning, tryckår och översättningsår.” År Författare Titel 1949 Vilhelm Moberg Utvandrarna Per Wästberg Pojke med såpbubblor 1950 Pär Lagerkvist Barabbas 1951 Ivar Lo-Johansson Analfabeten Åke Löfgren Historien om någon 1952 Ulla Isaksson Kvinnohuset 1953 Nevil Shute Livets väv Astrid Lindgren Kalle Blomkvist och Rasmus 1954 William Golding Flugornas herre Simone de Beauvoir Mandarinerna 1955 Astrid Lindgren Lillebror och Karlsson på taket 1956 Agnar Mykle Sången om den röda rubinen Siri Ahl Två små skolkamrater 1957 Enid Blyton Fem följer ett spår 1958 Yaşar Kemal Låt tistlarna brinna Åke Wassing Dödgrävarens pojke Leon Uris Exodus 1959 Jan Fridegård Svensk soldat 1960 Per Wästberg På svarta listan Gösta Gustaf-Jansson Pärlemor 1961 John Åberg Över förbjuden gräns 1962 Lars Görling 491 1963 Dag Hammarskjöld Vägmärken Ann Smith Två i stjärnan 1964 P.O. E n q u i st Magnetisörens femte vinter 1965 Göran Sonnevi ingrepp-modeller Ernesto Cardenal Förlora inte tålamodet 1966 Truman Capote Med kallt blod 1967 Sven Lindqvist Myten om Wu Tao-tzu Gabriel García Márques Hundra år av ensamhet 1968 P.O. E n q u i st Legionärerna Vassilis Vassilikos Z Jannis Ritsos Greklands folk: dikter 1969 Göran Sonnevi Det gäller oss Björn Håkansson Bevisa vår demokrati 1970 Pär Wästberg Vattenslottet Göran Sonnevi Det måste gå 1971 Ylva Eggehorn Ska vi dela 1972 Maja Ekelöf & Tony Rosendahl Brev 1 År Författare Titel 1973 Lars Gustafsson Yllet 1974 Kerstin Ekman Häxringarna Elsa Morante Historien 1975 Alice Lyttkens Fader okänd Mari Cardinal Orden som befriar 1976 Ulf Lundell Jack 1977 Sara Lidman Din tjänare hör P.G . -

From a Safe Distance – Swedish Portrayal of World War II. Astrid Lindgren: Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945

ZESZYTY NAUKOWE TOWARZYSTWA DOKTORANTÓW UJ NAUKI HUMANISTYCZNE, NR 23 (4/2018), S. 109–119 E-ISSN 2082-9469 | P-ISSN 2299-1638 WWW.DOKTORANCI.UJ.EDU.PL/ZESZYTY/NAUKI-HUMANISTYCZNE DOI: 10.26361/ZNTDH.09.2018.23.07 SONIA ŁAWNICZAK ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ FACULTY OF MODERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES DEPARTMENT OF SCANDINAVIAN STUDIES E-MAIL: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________ From a Safe Distance – Swedish Portrayal of World War II. Astrid Lindgren: Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945 ABSTRACT The article refers to the latest methodological reflections on the remembrance culture and presents one of the forms of Swedish collective memory thematization. The 1990s brought an increased interest of the Swedish people in the history of their own country and debates on the stance taken by Sweden during World War II. Diaries, memoires, autobiographic and documentary novels about World War II and the Holocaust gained recognition among Swedish researchers and readers. Among the latest prose works, coming under this thematic heading, Krigsdagböcker 1939–1945 (War Diaries 1939– 1945) by Astrid Lindgren, published posthumously in 2015, merit attention. When analyzing the image of World War II presented in the diaries, the following issues were taken into account: the image of everyday life of the Swedes during World War II, the state of knowledge of the situation in Europe and the attitude towards the Swedish neutrality. KEYWORDS Astrid Lindgren, Swedish literature, World War II, Holocaust, collective memory, re- membrance Introduction The 20th century was one of the most tragic periods in the history of man- kind; it witnessed two world wars, attempts to implement the criminal ide- ologies of Nazism and communism and mass murders. -

Poesier & Kombinationer Bruno K. Öijers Intermediala Poesi Askander

Poesier & kombinationer Bruno K. Öijers intermediala poesi Askander, Mikael 2017 Document Version: Förlagets slutgiltiga version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Askander, M. (2017). Poesier & kombinationer: Bruno K. Öijers intermediala poesi. (Lund Studies in Arts and Cultural Sciences; Vol. 12). Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Mikael Askander Poesier & kombinationer BRUNO K. ÖIJERS INTERMEDIALA POESI LUND STUDIES IN ARTS AND CULTURAL SCIENCES 12 Bruno K. Öijer är ett av de mest centrala namnen i den moderna svenska litteraturen. Alltifrån debuten 1973, med diktsamlingen Sång för anarkismen, till idag har hans dikter nått stora skaror av läsare. -

Skandinavische Erzähler Des 20. Jahrhunderts

SKANDINAVISCHE ERZÄHLER DES 20. JAHRHUNDERTS Herausgegeben und ausgewählt von Manfred Kluge WILHELM HEYNE VERLAG MÜNCHEN Inhalt DANEMARK MARTIN ANDERSEN NEX0 Jakobs wunderbare Reise 10 TANIA BLIXEN Die Perlen 17 WILLIAM HEINESEN Gäste vom Mond 35 HANS CHRISTIAN BRANNER Zwei Minuten Schweigen 39 TOVE DITLEVSEN Gesichter 51 LEIF PANDURO Röslein auf der Heide 59 VILLY S0RENSEN Der Heimweg 72 KLAUS RIFBJERG Die Badeanstalt 81 INGER CHRISTENSEN Nataljas Erzählung 90 SVEN HOLM Hinrichtung 101 PETER H0EG Carl Laurids 109 FINNLAND FRANS EEMIL SILLANPÄÄ Rückblick 132 TOIVO PEKKANEN Ein Träumer kommt aufs Schiff 152 MARJA-LIISA VARTIO Finnische Landschaft 158 VEIJO MERI Der Töter 168 ANTTI HYRY Beschreibung einer Bahnfahrt 179 MÄRTA TIKKANEN Ich schau nur mal rein 195 ANTTI TUURI 650 nördlicher Breite 206 ROSA LIKSOU Ich hab einen schrottreifen Motorschlitten 217 ISLAND GUNNAR GUNNARSSON Die dunklen Berge 222 HALLDÖR LAXNESS Der Pfeifer 231 STEINUNN SIGURDARDÖTTIR Liebe auf den ersten Blick 247 EINAR KÄRASON Licht in der Finsternis 258 NORWEGEN KNUT HAMSUN Kleinstadtleben 278 SIGRID UNDSET Mädchen 298 GERD BRANTENBERG »Ein Mann wirft einen Schatten« 310 TORIL BREKKE Ein silberner Flachmann 324 INGVAR AMBJ0RNSEN Komm heim, komm heim! 330 JOSTEIN GAARDER ... wir werden herbeigezaubert und wieder weggejuxt... 336 ERIK FOSNES HANSEN Straßen der Kindheit, der Jugend 342 SCHWEDEN HJALMAR BERGMAN Befiehl, Karolina, befiehl 356 SELMA LAGERLÖF Der Roman einer Fischersfrau 365 PÄR LAGERKVIST Der Fahrstuhl, der zur Hölle fuhr 375 EYVIND JOHNSON September 38 382 HARRY MARTINSON Das Seemärchen, das nie passierte 388 LARS AHLIN Man kommt nach Haus und ist nett 395 WILLY KYRKLUND Die Sehnsucht der Seele 404 PER OLOF SUNDMAN Oskar 423 PER OLOV ENQUIST Der Gesang vom gestürzten Engel 436 LARS GUSTAFSSON Eine Wasser-Erzählung 446 LARS ANDERSSON Repja 463 STIG LARSSON Gogols Blick 472 Autoren- und Quellenverzeichnis 483. -

Littfest-Program2020-Web.Pdf

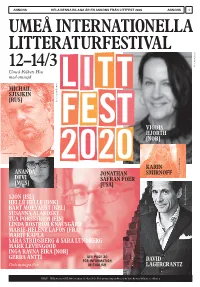

ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN ANNONS FRÅN LITTFEST 2020 ANNONS 1 UMEÅ INTERNATIONELLA LITTERATURFESTIVAL 12–14/3 Anette Brun Foto: Umeå Folkets Hus med omnejd MICHAIL SJISJKIN [RUS] Frolkova Jevgenija Foto: VIGDIS HJORTH [NOR] KARIN ANANDA JONATHAN SMIRNOFF Gunséus Johan Foto: Obs! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda.se sidan För X programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, DEVI SAFRAN FOER [MUS] [USA] Foto: Foto: Timol Umar SJÓN [ISL] HELLE HELLE [DNK] Caroline Andersson Foto: BART MOEYAERT [BEL] SUSANNA ALAKOSKI TUA FORSSTRÖM [FIN] LINDA BOSTRÖM KNAUSGÅRD MARIE-HÉLÈNE LAFON [FRA] MARIT KAPLA SARA STRIDSBERG & SARA LUNDBERG MARK LEVENGOOD INGA RAVNA EIRA [NOR] GERDA ANTTI SEE PAGE 30 FOR INFORMATION DAVID Foto: Jeff Mermelstein Jeff Foto: Och många fler… IN ENGLISH LAGERCRANTZ IrmelieKrekin Foto: OBS! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda. För programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, se sidan 4 Olästa e-böcker? Odyr surf. Har du missat vårens hetaste boksläpp? Med vårt lokala bredband kan du surfa snabbt och smidigt till ett lågt pris, medan du kommer ikapp med e-läsningen. Vi kallar det för odyr surf – och du kan lita på att våra priser alltid är låga. Just nu beställer du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Odyrt och okrångligt = helt enkelt oslagbart! Beställ på odyrsurf.se P.S. Är du redan prenumerant på VK eller Folkbladet köper du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Efter kampanjperioden får du tio kronor rabatt per månad på ordinarie bredbandspris, så länge du är prenumerant. ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN -

09-29 Drömmen Om Jerusalem I Samarb. Med Svenska Kyrkan Och Piratförlaget 12.00

09-29 Tid 12.00 - 12.45 Drömmen om Jerusalem Drömmen om Jerusalem realiserades av Jerusalemsfararna från Nås som ville invänta Messias ankomst på plats. Vissa kristna grupper, ibland benämnda kristna sionister, kämpar för staten Israel och för att alla judar ska återföras till Israel – men med egoistiska syften. När alla judar återvänt till det heliga landet kommer Messias tillbaka för att upprätta ett kristet tusenårsrike, tror man. Dessa grupper har starka fästen i USA och anses ha betydande inflytande i amerikansk utrikespolitik. De söker också aktivt etablera sig som maktfaktor i Europa. Kan man verkligen skilja mellan religion och politik i Israel-Palestinakonflikten? Är det de extremreligiösa grupperingarna som gjort en politisk konflikt till en religiös konflikt? Medverkande: Jan Guillou, författare och journalist, Mia Gröndahl, journalist och fotograf, Cecilia Uddén, journalist, Göran Hägglund, partiledare för Kristdemokraterna. Moderator: Göran Gunner, forskare, Svenska kyrkan. I samarb. med Svenska kyrkan och Piratförlaget 09-29 Tid 16.00 - 16.45 Små länder, stora frågor – varför medlar Norge och Sverige? Norge och Sverige har spelat en stor roll vid internationella konflikter. Tryggve Lie och Dag Hammarskjöld verkade som FN:s generalsekreterare. I dagens världspolitik är svenskar och norrmän aktiva i konfliktområden som Östra Timor, Sri Lanka, Colombia och Mellanöstern. Hur kommer det sig att så små nationer som Norge och Sverige fått fram en rad framstående personer inom freds- och konflikthantering? Medverkande: Lena Hjelm-Wallén, tidigare utrikesminister, Kjell-Åke Nordquist, lektor i freds- och konfliktforskning vid Uppsala universitet, Erik Solheim, specialrådgivare till Norska UD. Moderator: Cecilia Uddén, journalist. I samarb. med Svenska kyrkan och Norges ambassad i Stockholm 09-29 Tid 17.00 - 17.45 Vem skriver manus till mitt liv? Film och religion – livsåskådning på vita duken De avgörande föreställningarna för hur det goda livet ser ut formas i vår tid av filmer, TV-serier, varumärken, logotyper och reklambudskap. -

Francisco J. Uriz: "No Soy Un Teórico, Soy Un Trabajador"

Francisco J. Uriz: "No soy un teórico, soy un trabajador" Juan Marqués l 19 de abril de 2015, muy pocos días antes de que Francisco J. Uriz y su mujer, Marina Torres, volasen a Estocolmo para pasar allí la temporada estival, visité al matrimonio en su domicilio de la calle Valencia de Zaragoza y, antes de probar el legen darioE salmón al eneldo de Uriz y el no menos sobresaliente tiramisú de Marina, mantuve con él la conversación que aquí se transcribe, mientras ella leía el periódico en el salón y aderezaba la charla con comentarios perspicaces y divertidos. Cuando lo conocí en nuestra ciudad, durante una comida que organizó Diego Moreno, editor de Nórdica Libros, el 3 de noviembre de 2011, mi timidez me impidió explicarle cuánto le debo, pero lo cierto es que, pensándolo bien, no creo haber leído nunca más versos de nadie, si contamos como suyos todos aquellos que él ha traído desde el idioma sueco al español. Y, teniendo en cuenta la aplastante calidad de muchísimos de los autores que gracias a él conocemos, es de justicia declarar que pocas personas me han proporcionado tantas horas de jolgorio lector, de felicidad solitaria y privada. Intenté explicarlo con un poco de orden y también un punto de desenfado en el artículo "Algo de lo que debemos a Uriz", publicado en el número 6 de la revista zaragozana Crisis, y después, con más espacio y seriedad, en el volumen 113-114 de la turolense Turia, donde volvía sobre sus traducciones y sobre todo analizaba su propia obra poética, menos conocida pero igualmente valiosa.