Forced Displacement by the Boko Haram Conflict in the Lake Chad Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 – 03/07/2020 Humanitarian Implementation Plan (Hip)

Year: 2020 Version: 5 – 03/07/2020 HUMANITARIAN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (HIP) CENTRAL AFRICA1 The full implementation of this version of the HIP is conditional upon the necessary appropriation being made available from the 2020 general budget of the European Union AMOUNT: EUR 117 200 000 The present Humanitarian Implementation Plan (HIP) was prepared on the basis of the financing decision ECHO/WWD/BUD/2020/01000 (Worldwide Decision) and the related General Guidelines for Operational Priorities on Humanitarian Aid (Operational Priorities). The purpose of the HIP and its annex is to serve as a communication tool for DG ECHO2's partners and to assist them in the preparation of their proposals. The provisions of the Worldwide Decision and the General Conditions of the Agreement with the European Commission shall take precedence over the provisions in this document. This HIP covers Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad and Nigeria. It may also respond to sudden or slow-onset new emergencies in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé and Principe, if important unmet humanitarian needs emerge, given the exposure to risk and vulnerabilities of populations in these countries. 0. MAJOR CHANGES SINCE PREVIOUS VERSION OF THE HIP Fourth modification as of 03/07/2020 The total budget of the HIP is increased by EUR 5 million (Central African Republic: EUR 5 million). The perspectives in the Central African Republic for 2020 are very worrisome and the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate needs in all sectors. This additional funding will cover unmet needs. The eligible sectors in CAR are: (i) protection (ii) health and nutrition, (iii) food assistance and livelihoods, (iv) water, sanitation and hygiene, (v) shelter (vi) emergency preparedness and response and (vii) education in emergencies. -

NIGER - DIFFA : Les Incidents Liés Au Groupe Boko Haram* (1 Janvier Au 31 Août 2018)

NIGER - DIFFA : Les incidents liés au groupe Boko Haram* (1 janvier au 31 août 2018) De janvier à août 2018, la situation sécuritaire dans la région de Diffa a été marquée par une augmentation des exactions des éléments du groupe armé non étatique Boko Haram (BH) et une baisse des victimes civiles liées à ces incidents comparativement à la même période l’année dernière (2017). Les mois de janvier et août 2018 ont enregistré le plus d’incidents (47/94 soit 50%). Les communes de Gueskerou, Bosso, Maine Soroa et Chetimari sont les plus touchées par les attaques du groupe BH (73/94 incidents soit 78%). Des attaques terroristes majeures ont été rapportées dans les localités bordant les berges de la Komadougou et les localités proches des îles du Lac Tchad. Le 4 juin, 3 kamikazes ont fait exploser leurs charges dans un quartier de la ville de Diffa tuant 6 civils. Trois (3) bases militaires ont été attaquées par les éléments du groupe BH respectivement les 17 janvier, 23 janvier et 1 juillet dans les localités de Toumour, Chétima Wangou (Chetimari) et Bilabrin (N’Guigmi) faisant des victimes dans les deux camps. Ces incidents et d’autres de nature criminelle (enlèvements, extorsions et menaces) sont à l’origine de mouvements de populations entre les différents sites et/ou villages. Bilan des incidents Les incidents par commune en 2018 Les incidents par mois 94 incidents de janv. à août 2018 Pertes en vies 38 humaines 60 incidents de janv. à août 2017 (janv. à août 2018) 30 24 23 Pertes en vies 25 56 humaines 20 15 15 (2017) 10 0 5 0 1-5 Enlèvements Ngourti Jui Jul Avr Oct Déc. -

Assessment Report

Needs Assessment for Self-Reliance of CAR refugees in Gado, Borgop, Ngam, Mbile, Lolo and Timangolo Camps, and In Touboro Assessment Report Monitoring & Evaluation department November-December 2017 Page 1 of 30 Contents List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Key findings/executive summary .................................................................................................................. 5 Operational Context ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction: The CAR situation In Cameroon .............................................................................................. 7 Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Study Design ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Qualitative Approach ........................................................................................................................... -

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

Taxes, Institutions, and Governance: Evidence from Colonial Nigeria

Taxes, Institutions and Local Governance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Colonial Nigeria Daniel Berger September 7, 2009 Abstract Can local colonial institutions continue to affect people's lives nearly 50 years after decolo- nization? Can meaningful differences in local institutions persist within a single set of national incentives? The literature on colonial legacies has largely focused on cross country comparisons between former French and British colonies, large-n cross sectional analysis using instrumental variables, or on case studies. I focus on the within-country governance effects of local insti- tutions to avoid the problems of endogeneity, missing variables, and unobserved heterogeneity common in the institutions literature. I show that different colonial tax institutions within Nigeria implemented by the British for reasons exogenous to local conditions led to different present day quality of governance. People living in areas where the colonial tax system required more bureaucratic capacity are much happier with their government, and receive more compe- tent government services, than people living in nearby areas where colonialism did not build bureaucratic capacity. Author's Note: I would like to thank David Laitin, Adam Przeworski, Shanker Satyanath and David Stasavage for their invaluable advice, as well as all the participants in the NYU predissertation seminar. All errors, of course, remain my own. Do local institutions matter? Can diverse local institutions persist within a single country or will they be driven to convergence? Do decisions about local government structure made by colonial governments a century ago matter today? This paper addresses these issues by looking at local institutions and local public goods provision in Nigeria. -

Tracking Displacement in the Lake Chad Basin

WITHIN AND BEYOND BORDERS: TRACKING DISPLACEMENT IN THE LAKE CHAD BASIN Regional Displacement and Human Mobility Analysis Displacement Tracking Matrix December 2016 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION (IOM) DTM activities are supported by: Chad │Cameroon│Nigeria 1 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community: to assist in meeting the growing operational challenges of migration management; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. PUBLISHER International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for West and Central Africa, Dakar, Senegal © 2016 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 IOM Regional Displacement Tracking Matrix INTRODUCTION Understanding and analysis of data, trends and patterns of human mobility is key to the provision of relevant and targeted humanitarian assistance. Humanitarian actors require information on the location and composition of the affected population in order to deliver services and respond to needs in a timely manner. -

Republique Du Niger Region De Diffa Direction Regionale De L'etat Civil Et Des Refugies

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER REGION DE DIFFA DIRECTION REGIONALE DE L'ETAT CIVIL ET DES REFUGIES Situtation des refugiés et retournés mise à jour 24/11/2015 N° Site RGP/H 2012 Menages Personnes Refugiés Retournés 1 Diffa festibal 508 3 229 1 619 1 610 2 Diffa Affounori 187 1 040 695 345 3 Diffa Administratif 31 173 162 11 4 Diffa Koura 604 3 483 2 442 1 041 5 Diffa Château 554 3 956 2 658 1 298 6 Diffa Sabon Carré 684 5 902 3 661 2 241 7 Adjimeri 419 1 691 1 127 564 8 Bagara 67 478 159 319 9 Grema Artori 99 436 317 119 10 Boulangouri 82 462 395 67 11 Lada 149 703 604 99 12 Guirtia 20 112 84 28 13 Ngueldagoumé 50 382 0 382 14 Boulangou Yakou 31 195 158 37 15 Kayawa 97 507 269 238 16 Koula koura 256 554 332 222 17 Madou Kaouri 61 912 585 327 18 Ligaridi 107 629 337 292 19 Dorikoulo 43 306 158 148 Total Diffa 159 722 4049 25 150 15 762 9 388 20 Mainé Boudji Kolomi 156 1 865 1695 670 21 Mainé Abdouri 25 182 195 109 22 Mainé Djambourou 112 1 574 1049 525 23 Mainé Katiellari 3 16 0 16 24 Mainé Dekouram 1 11 0 11 25 Mainé Angoual Yamma 295 2 066 1 113 953 26 Mainé Château 222 2 824 1 777 1 047 27 Mainé Yabal 16 87 76 11 28 Mainé Alaouri 36 301 92 209 29 Mainé Kaoumaram 26 201 93 108 30 Mainé Goussougourniram 23 136 0 136 31 Mainé Nguibia 19 84 13 71 32 Mainé Gadori 97 559 434 125 33 Mainé Abbasari 57 692 594 98 34 Mainé Kilwadji 20 135 61 74 35 Mainé Baredi 3 28 9 19 36 Mainé Ambouram Ali 174 864 714 150 37 Mainé Issari Bagara 22 129 0 129 38 Mainé Tam 107 957 291 666 39 Mainé Kayetawa 23 120 16 104 40 Cheri 30 140 48 92 41 Ambouram 38 198 68 130 42 -

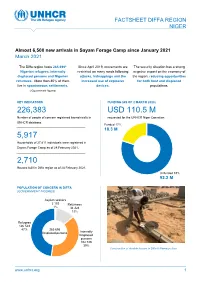

UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR Database

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION NIGER Almost 6,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp since January 2021 March 2021 NNNovember The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 2 MARCH 2020) 226,383 USD 110.5 M Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR database. Funded 17% 18.3 M 5,917 Households of 27,811 individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp as of 28 February 2021. 2,710 Houses built in Diffa region as of 28 February 2021. Unfunded 83% 92.2 M the UNHCR Niger Operation POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% 265 696 Displaced persons Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% Construction of durable houses in Diffa © Ramatou Issa www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / March 2021 Operation Strategy The key pillars of the UNHCR strategy for the Diffa region are: ■ Ensure institutional resilience through capacity development and support to the authorities (locally elected and administrative authorities) in the framework of the Niger decentralisation process. ■ Strengthen the out of camp policy around the urbanisation program through sustainable interventions and dynamic partnerships including with the World Bank. -

The Onward Migration of Nigerians in Europe

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Imagined Futures: The Onward Migration of Nigerians in Europe Jill Ahrens Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Geography School of Global Studies University of Sussex June 2017 ii Summary of Thesis Dynamic mobility and migration patterns, including forced migration, have always formed part of the complex social, cultural and economic relationships between Africa and Europe. Like other Africans, Nigerian migrants live in countless locations around the world and are connected to their homeland through contingent transnational networks. This thesis explores the onward migration of Nigerian migrants towards, within and beyond Europe and analyses the motivations, patterns and outcomes of their multiple movements. Six cities in Germany, the UK and Spain are the main research locations for the fieldwork that took place over 17 months. The three countries are important destinations for Nigerian migrants in Europe and also the principal destinations of intra-European onward migrants. The cities included in this study are the capital cities Berlin, London and Madrid, as well as Cologne, Manchester and Málaga. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of Cerf Funds Niger Rapid Response Conflict-Related Displacement

RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS NIGER RAPID RESPONSE CONFLICT-RELATED DISPLACEMENT RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Mr. Fodé Ndiaye REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Since the implementation of the response started, OCHA has regularly asked partners to update a matrix related to the state of implementation of activities, as well as geographical location of activities. On February 26, CERF-focal points from all agencies concerned met to kick off the reporting process and establish a framework. This was followed up by submission of individual projects and input in the following weeks, as well as consolidation and consultation in terms of the draft for the report. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO The CERF Report has been shared with Cluster Coordinator and recipient agencies. 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: 53,047,888 Source Amount CERF 5,181,281 Breakdown -

Migration in Nigeria

This publication has been co-financed by the EU MMigrationigration in Nigeria A COUNTRY PROFILE 2009 Democratic Republic of the Congo 17 route des Morillons, 1211 Geneva 19, Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 • Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.iom.int The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. Omissions and errors remain the responsibility of the authors. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This publication was made possible through the financial support provided by the European Union, the Swiss Federal Office for Migration (FOM) and the Belgian Development Cooperation. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Swiss Federal Office for Migration (FOM), nor the Belgian Development Cooperation. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 91 11 Fax: +41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.iom.int _____________________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-569-2 © 2009 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________________ All rights reserved.