Envisioning a Compulsory-Licensing System for Digital Samples Through Emergent Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

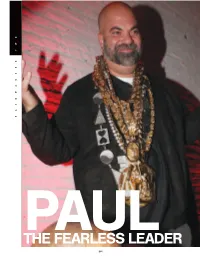

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Download Bones Album Download Bones Album

download bones album Download bones album. Artist: Bones Album: Offline Released: 2020 Style: Hip Hop. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Offline 02 – BewareOfDog 03 – Timberlake 04 – Molotov 05 – Vertigo 06 – ChampagneInTheGraveyard 07 – Numb 08 – IWasYourTomb 09 – StateOfEmergency 10 – BlancoBenz 11 – 240p 12 – Kerosene 13 – YouWantTheGoodNewsOrBadNews 14 – FatherTime 15 – GlassHalfFull 16 – JimmyWalker. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. DOWNLOAD MP3. Talented Chocolate City Rapper, Blaqbonez unleashed out his much anticipated studio project titled “ Sex Over Love ” album and it’s made available for you on this platform. The new project “ Sex Over Love Album ” houses 13 solid tracks with outside collaborations with the likes of Laycon, Tiwa savage, Joeboy, Badboy Timz e.t.c. Blaqbonez Sex Over Love album tracklist; 1. Blaqbonez – Novacane || DOWNLOAD MP3. 2. Blaqbonez Ft. Nasty C – Heartbreaker || DOWNLOAD MP3. 3. Blaqbonez Ft. Amaarae & Buju – Bling || DOWNLOAD MP3. 4. Blaqbonez – Never Been In Love || DOWNLOAD MP3. 5. Blaqbonez – Don’t Touch || DOWNLOAD MP3. 6. Blaqbonez – TGF Pussy || DOWNLOAD MP3. 7. Blaqbonez – Okwaraji || DOWNLOAD MP3. 8. Blaqbonez Ft. Joeboy – Fendi || DOWNLOAD MP3. 9. Blaqbonez Ft. Tiwa Savage – BBC (Remix) || DOWNLOAD MP3. 10. Blaqbonez Ft. Bad Boy Timz & 1da Banton – Faaji || DOWNLOAD MP3. 11. Blaqbonez Ft. Laycon, PsychoYP & AQ – Zombie || DOWNLOAD MP3. 12. Blaqbonez Ft. Cheque – Best Friend || DOWNLOAD MP3. 13. Blaqbonez – Cynic Route || DOWNLOAD MP3. [Full Album] BONES – InLovingMemory. InLovingMemory is BONES‘ 3rd album in 2021. The album have no beats/insturmentals in itself. Album contains both chill and hard songs. As a promotional act, the bear similar to the one in the cover art was left on the streets of LA just before the album release. -

Digitale Disconnectie Voor De La Soul

juridisch Digitale disconnectie dreigt voor hiphopgroep De La Soul Stakes Is High Bjorn Schipper Met de lancering op Netflix van de nieuwe hitserie The Get Down staat de opkomst van hiphop weer volop in de belangstelling. Tegen de achtergrond van de New Yorkse wijk The Bronx in de jaren ’70 krijgt de kijker een beeld van hoe discomuziek langzaam plaatsmaakte voor hiphop en hoe breakdancen en deejayen in zwang raakten. Een hiphopgroep die later furore maakte is De La Soul. In een tijd waarin digitale exploitatie volwassen is geworden en de online-mogelijkhe- den haast eindeloos zijn, werd onlangs bekend dat voor De La Soul juist digitale disconnectie dreigt met een nieuwe generatie (potentiële) fans1. In deze bijdrage ga ik in op de bizarre digi- tale problemen van De La Soul en laat ik zien dat ook andere artiesten hiermee geconfronteerd kunnen worden. De La Soul: ‘Stakes Is High’ Net als andere hiphopalbums2 bevatten de albums van De New Yorkse hiphopgroep De La Soul bestaat De La Soul vele samples. Dat bleef juridisch niet zon- uit Kelvin Mercer, David Jude Jolicoeur en Vincent der gevolgen en zorgde voor kopzorgen in verband met Mason. De La Soul brak in 1989 direct door met het het clearen van de gebruikte samples. Niet zo vreemd album 3 Feet High and Rising en kreeg vooral door ook als we bedenken dat in die tijd weinig jurispruden- de tekstuele inhoud en het gekleurde hoesontwerp al tie bestond over (sound)sampling. Zo kreeg De La Soul snel een hippie-achtig imago aangemeten. Met hun het na de release in 1989 van 3 Feet High and Rising vaste producer Prince Paul bewees De La Soul dat er aan de stok met de band The Turtles. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (Guest Post)*

“3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (guest post)* De La Soul For hip-hop, the late 1980’s was a tinderbox of possibility. The music had already raised its voice over tensions stemming from the “crack epidemic,” from Reagan-era politics, and an inner city community hit hard by failing policies of policing and an underfunded education system--a general energy rife with tension and desperation. From coast to coast, groundbreaking albums from Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” to N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” were expressing an unprecedented line of fire into American musical and political norms. The line was drawn and now the stage was set for an unparalleled time of creativity, righteousness and possibility in hip-hop. Enter De La Soul. De La Soul didn’t just open the door to the possibility of being different. They kicked it in. If the preceding generation took hip-hop from the park jams and revolutionary commentary to lay the foundation of a burgeoning hip-hop music industry, De La Soul was going to take that foundation and flip it. The kids on the outside who were a little different, dressed different and had a sense of humor and experimentation for days. In 1987, a trio from Long Island, NY--Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo, P.A. Pasemaster Mase and Plug Three” Mason—were classmates at Amityville Memorial High in the “black belt” enclave of Long Island were dusting off their parents’ record collections and digging into the possibilities of rhyming over breaks like the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President” all the while immersing themselves in the imperfections and dust-laden loops and interludes of early funk and soul albums. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 12-14-2020 Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music Cervanté Pope Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Pope, Cervanté, "Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music" (2020). University Honors Theses. Paper 957. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music By Cervanté Pope Student ID #: 947767021 Portland State University Pope 2 Introduction In mass communication, gatekeeping refers to how information is edited, shaped and controlled in efforts to construct a “social reality” (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley, 2001). Gatekeeping has expanded into other fields throughout the years, with its concepts growing more and more easily applicable in many other aspects of life. One way it presents itself is in regard to racial inclusion and equality, and despite the headway we’ve seemingly made as a society, we are still lightyears away from where we need to be. Because of this, the concept of cultural property has become even more paramount, as a means for keeping one’s cultural history and identity preserved. -

De La Soul the Best of Mp3, Flac, Wma

De La Soul The Best Of mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: The Best Of Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Conscious MP3 version RAR size: 1691 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1383 mb WMA version RAR size: 1102 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 577 Other Formats: MP4 MPC WAV VOC FLAC VOX APE Tracklist Hide Credits Me Myself And I (Radio Version) A1 3:41 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul Say No Go A2 4:20 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul Eye Know A3 4:06 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul The Magic Number A4 3:14 Co-producer, Arranged By – De La SoulProducer, Mixed By – Prince Paul Potholes In My Lawn (12" Vocal Version) B1 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer, Mixed By, Arranged 3:46 By – Prince Paul Buddy B2 Arranged By – PosdnuosCo-producer – De La SoulFeaturing – Jungle Brothers, Phife*, Q- 4:56 TipMixed By – Pasemaster MaseProducer – Prince Paul Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey) (UK 7" Edit) B3 5:06 Mixed By – Bob PowerProducer – Prince PaulProducer, Mixed By – De La Soul A Roller Skating Jam Named "Saturdays" B4 Producer – De La Soul, Prince PaulVocals [Disco Diva Singer] – Vinia MojicaVocals [Wrms 4:02 Personality] – Russell Simmons Keepin' The Faith C1 4:45 Producer – De La Soul, Prince Paul Breakadawn C2 4:14 Producer [Additional], Mixed By – Bob PowerProducer, Mixed By – De La Soul, Prince Paul Stakes Is High C3 5:30 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By – Tim LathamProducer – Jay Dee 4 More C4 4:18 Co-producer – De La SoulFeaturing – ZhanéMixed By – Tim LathamProducer – Ogee* Oooh. -

FM 4-02 Force Health Protection in a Global Environment

FM 4-02 (FM 8-10) FORCE HEALTH PROTECTION IN A GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FEBRUARY 2003 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. *FM 4-02 (FM 8-10) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS NO. 4-02 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 13 February 2003 FORCE HEALTH PROTECTION IN A GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .......................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. FORCE HEALTH PROTECTION ............................................ 1-1 1-1. Overview ............................................................................. 1-1 1-2. Joint Vision 2020 ................................................................... 1-1 1-3. Joint Health Service Support Vision ............................................. 1-1 1-4. Healthy and Fit Force .............................................................. 1-1 1-5. Casualty Prevention ................................................................ 1-2 1-6. Casualty Care and Management .................................................. 1-2 CHAPTER 2. FUNDAMENTALS OF FORCE HEALTH PROTECTION IN A GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT ................................................ 2-1 2-1. The Health Service Support System ............................................. 2-1 2-2. Principles of Force Health Protection in a Global Environment ............ 2-2 2-3. The Medical Threat and Medical Intelligence Preparation of the Battle- field .............................................................................. -

Nu-Metal As Reflexive Art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Porcello, Niccolo, "Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 580. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFFECTIVE!MASCULINITES!AND!SUBURBAN!IDENTITIES:!! NU2METAL!AS!REFLEXIVE!ART! ! ! ! ! ! Niccolo&Dante&Porcello& April&25,&2016& & & & & & & Senior&Thesis& & Submitted&in&partial&fulfillment&of&the&requirements& for&the&Bachelor&of&Arts&in&Urban&Studies&& & & & & & & & _________________________________________ &&&&&&&&&Adviser,&Leonard&Nevarez& & & & & & & _________________________________________& Adviser,&Justin&Patch& Porcello 1 This thesis is dedicated to my brother, who gave me everything, and also his CD case when he left for college. Porcello 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Click Click Boom .............................................................................................