Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

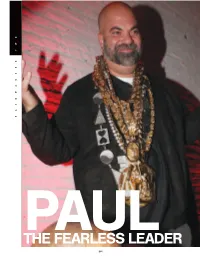

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

Download Bones Album Download Bones Album

download bones album Download bones album. Artist: Bones Album: Offline Released: 2020 Style: Hip Hop. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Offline 02 – BewareOfDog 03 – Timberlake 04 – Molotov 05 – Vertigo 06 – ChampagneInTheGraveyard 07 – Numb 08 – IWasYourTomb 09 – StateOfEmergency 10 – BlancoBenz 11 – 240p 12 – Kerosene 13 – YouWantTheGoodNewsOrBadNews 14 – FatherTime 15 – GlassHalfFull 16 – JimmyWalker. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. DOWNLOAD MP3. Talented Chocolate City Rapper, Blaqbonez unleashed out his much anticipated studio project titled “ Sex Over Love ” album and it’s made available for you on this platform. The new project “ Sex Over Love Album ” houses 13 solid tracks with outside collaborations with the likes of Laycon, Tiwa savage, Joeboy, Badboy Timz e.t.c. Blaqbonez Sex Over Love album tracklist; 1. Blaqbonez – Novacane || DOWNLOAD MP3. 2. Blaqbonez Ft. Nasty C – Heartbreaker || DOWNLOAD MP3. 3. Blaqbonez Ft. Amaarae & Buju – Bling || DOWNLOAD MP3. 4. Blaqbonez – Never Been In Love || DOWNLOAD MP3. 5. Blaqbonez – Don’t Touch || DOWNLOAD MP3. 6. Blaqbonez – TGF Pussy || DOWNLOAD MP3. 7. Blaqbonez – Okwaraji || DOWNLOAD MP3. 8. Blaqbonez Ft. Joeboy – Fendi || DOWNLOAD MP3. 9. Blaqbonez Ft. Tiwa Savage – BBC (Remix) || DOWNLOAD MP3. 10. Blaqbonez Ft. Bad Boy Timz & 1da Banton – Faaji || DOWNLOAD MP3. 11. Blaqbonez Ft. Laycon, PsychoYP & AQ – Zombie || DOWNLOAD MP3. 12. Blaqbonez Ft. Cheque – Best Friend || DOWNLOAD MP3. 13. Blaqbonez – Cynic Route || DOWNLOAD MP3. [Full Album] BONES – InLovingMemory. InLovingMemory is BONES‘ 3rd album in 2021. The album have no beats/insturmentals in itself. Album contains both chill and hard songs. As a promotional act, the bear similar to the one in the cover art was left on the streets of LA just before the album release. -

Rapparen & Gourmetkocken Action Bronson Tillbaka Med Nytt Album

2015-03-03 10:31 CET Rapparen & gourmetkocken Action Bronson tillbaka med nytt album Hiphoparen och kocken Arian Asllani, aka Action Bronson, från Queens New York släpper nya albumet Mr. Wonderful den 25 mars. Bronson har med flertalet album, EP’s och mixtapes i ryggen gjort sig ett namn som en utav vår tids bästa rappare. Det sätt han levererar sitt artisteri och kombinerar sina rapfärdigheter med humor, självdistans och genomgående matreferenser gör honom unik i musikvärlden. Innan Bronson påbörjade sin karriär som rappare, som ursprungligen endast var en hobby för honom, var han en respekterad gourmetkock i New York City. Han drev sin egen online matlagnings show med titeln "Action In The Kitchen". Efter att han bröt benet i köket bestämde han sig för att enbart koncentrera sig på musiken. Debutalbumet Dr. Lecter släpptes 2011 såväl som ett par mixtapes, däribland Blue Chips. Sent år 2012 signade rapparen med Warner Music via medieföretaget VICE och för två år sedan släppte han EP’n Saaab Stories samt spelade på en av världens viktigaste musikfestivaler, nämligen Coachella Music Festival. Genom åren har han haft samarbeten med flera stor rappare såsom Wiz Khalifa, Raekwon, Eminem och Kendrick Lamar. Enligt Bronson är det kommande albumet hans bästa verk hittills. “I gave this my most incredible effort,” säger han. “If you listen to everything I’ve put out and then listen to this you’ll hear the steps that I’ve taken to go all out and show progression.” Singeln Baby Blue ft. Chance The Rapper, producerad av Mark Ronson, premiärspelades igår av Zane Lowe på BBC Radio 1. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

ORAL HISTORY PROJECT in Celebration of the City of Sugar Land 60Th Anniversary

ORAL HISTORY PROJECT in Celebration of the City of Sugar Land 60th Anniversary GOODSILL: What brought your family to Sugar Land, Billy? GOODSILL: What is William Alfred Streich’s story? STRITCH: My grandmother, Mary Alice Blair, was born in STRITCH: I never knew my grandfather. He died before I was Blessing, Texas, but her family moved to Sugar Land early in her born, in 1957 or so. My older sister is the only one who vaguely life. My grandmother and Buddy Blair were cousins. Mary Alice remembers him. He worked for a philanthropist in Houston whose was one of the founding families of First Presbyterian Church in name was Alonzo Welch. He had a foundation, the Welch Foundation, Sugar Land, founded in 1920 or so. There is definitely a Sugar which started in 1954, two years after Welch’s death in 1952. My Land connection that goes way back for us. grandfather was Mr. Welch’s right hand man. I know this through stories my grandmother told me over the years. At the time she married my dad, William Alfred Striech, they lived in Houston, where I was born in 1962. When I was about My dad who was an only child, who was raised in Houston. He went one, they decided to move out to Sugar Land and build a house. to Texas A & M for college and directly into the service afterward. He [Editor’s note: Striech was the original spelling of the name. Billy served two years in the Air Force. He met and married my mother, Jane goes by Stritch.] Toffelmire, during the course of the war. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Language Contact and US-Latin Hip Hop on Youtube

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research York College 2019 Choutouts: Language Contact and US-Latin Hip Hop on YouTube Matt Garley CUNY York College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/yc_pubs/251 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Choutouts: Language contact and US-Latin hip hop on YouTube Matt Garley This paper presents a corpus-sociolinguistic analysis of lyrics and com- ments from videos for four US-Latinx hip hop songs on YouTube. A ‘post-varieties’ (Seargeant and Tagg 2011) analysis of the diversity and hybridity of linguistic production in the YouTube comments finds the notions of codemeshing and plurilingualism (Canagarajah 2009) useful in characterizing the language practices of the Chicanx community of the Southwestern US, while a focus on the linguistic practices of com- menters on Northeastern ‘core’ artists’ tracks validate the use of named language varieties in examining language attitudes and ideologies as they emerge in commenters’ discussions. Finally, this article advances the sociolinguistics of orthography (Sebba 2007) by examining the social meanings of a vast array of creative and novel orthographic forms, which often blur the supposed lines between language varieties. Keywords: Latinx, hip hop, orthography, codemeshing, language contact, language attitudes, language ideologies, computer-mediated discourse. Choutouts: contacto lingüístico y el hip hop latinx-estadounidense en YouTube. Este estudio presenta un análisis sociolingüístico de letras de canciones y comentarios de cuatro videos de hip hop latinx-esta- dounidenses en YouTube. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Rcc the CCCCCD Brown Comes Back Strong, House of Pain Needs to Come Again

FEATURES SEPTEMBER 16, 1992 ] rcc THE CCCCCD Brown comes back strong, House of Pain needs to come again By TJ Stancil Of course, this album was the album in “Something in proud of Cypress Hill’s assistance Music Editor probably made before someone Common.” The album has slow on their album. decided to remix those tracks so jams in abundance as well as the With a song like “Jump Yo, what’s up everybody? I can’t throw out blame. The typical B. Brown dance floor jam, Around,” it would be assumed that I’m back wilh another year of album as is is a Neo-Reggae but the slow jams sometimes seem this album isp^etty hype. WRONG! giving you insight on what’s hot classic (in my opinion) which hollow since he obviously doesn’t Let me tell you why it is definitely and what ’ s not in black and urban should be looked at. Other songs mean them (or does he?). not milk. contemporary music. This year, of mention are ‘Them no care,” Also, some of the slow jams, the First, all of their songs, like with a new staff and new format. “Nuff Man a Dead,” and “Oh majority of which were written and Cypress Hill’s, talk about smoking Black Ink will go further than It’s You.” Enjoy the return of produced by L.A. and Babyface, blounts and getting messed up. before in the realm of African- Reggae, but beware cheap seem as though they would sound Secondly, most of the beats sound American journalism.