The Jack Benny Program. (March 28, 1948)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

{FREE} Showrunners : How to Run a Hit TV Show Ebook, Epub

SHOWRUNNERS : HOW TO RUN A HIT TV SHOW PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tara Bennett | 240 pages | 02 Sep 2014 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783293575 | English | London, United Kingdom Showrunners : How to Run a Hit TV Show PDF Book Good insight, but essentially just a transcript of the documentary of the same name. Open Preview See a Problem? The doorbell dings. TV ratings are a real measure of a showrunner's success. The film intends to show audiences the huge amount of work that goes into making sure their favorite TV series airs on time as well as the many challenges that showrunners have to overcome to make sure a new series makes it onto the schedules at all! In the past few years, the recognition of the showrunner has grown exponentially. Other Septembers, Many Americas. Find books coming soon in But taking the culmination of a half-dozen answers of a few lines each to a question, still gives Showrunners by Tara Bennett is a companion books to the documentary "Showrunners: The Art of Running a TV Show. If you are at all interested in becoming a writer for TV or for film, this book is for you. It's a great read and adaptation of of the documentary. Blood Brothers. Plus you can tell they both really CARE. Very interesting insight of showrunning and the tv show industry. I Told You So. Find lots more television-related content on the next page. I'm excited to watch the doc that goes along with it. These people are responsible for creating, writing and overseeing every element of production on one of the United State's biggest exports - television drama and comedy series. -

Discourse Types in Stand-Up Comedy Performances: an Example of Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.1.filani European Journal of Humour Research 3 (1) 41–60 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Discourse types in stand-up comedy performances: an example of Nigerian stand-up comedy Ibukun Filani PhD student, Department of English, University of Ibadan [email protected] Abstract The primary focus of this paper is to apply Discourse Type theory to stand-up comedy. To achieve this, the study postulates two contexts in stand-up joking stories: context of the joke and context in the joke. The context of the joke, which is inflexible, embodies the collective beliefs of stand-up comedians and their audience, while the context in the joke, which is dynamic, is manifested by joking stories and it is made up of the joke utterance, participants in the joke and activity/situation in the joke. In any routine, the context of the joke interacts with the context in the joke and vice versa. For analytical purpose, the study derives data from the routines of male and female Nigerian stand-up comedians. The analysis reveals that stand-up comedians perform discourse types, which are specific communicative acts in the context of the joke, such as greeting/salutation, reporting and informing, which bifurcates into self- praising and self denigrating. Keywords: discourse types; stand-up comedy; contexts; jokes. 1. Introduction Humour and laughter have been described as cultural universal (Oring 2003). According to Schwarz (2010), humour represents a central aspect of everyday conversations and all humans participate in humorous speech and behaviour. This is why humour, together with its attendant effect- laughter, has been investigated in the field of linguistics and other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology. -

Soyouwanna Do Stand-Up Comedy? | Soyouwanna.Com 10/10/09 10:42 AM

SoYouWanna do stand-up comedy? | SoYouWanna.com 10/10/09 10:42 AM Search SYW SYWs SYWs by Questions How Tos HOME A to Z CATEGORY & Answers Sponsored Links Related Ads Comedian Casting Frank Caliendo in Vegas Comedy Circus Auditions, Open Calls for Comedian Add Laughter to Your Vegas Trip. Buy Def Comedy Jam Jobs.Talent Needed Urgently Frank Caliendo Tickets Today! Funny Comedy Casting-Call.us/Comedian www.MonteCarlo.com/FrankCaliendo Comedians Stand Up Comedy SOYOUWANNA DO STAND-UP COMEDY? Comedy Songs be a movie extra? get a talent agent? 1. Study the pros know about different fabrics 2. Gather material for your act for men's suits? write an impressive 3. Turn your material into a stand-up resume? routine register a trademark? 4. Find a place to perform 5. Earn money for being funny Sponsored Links Improv Comedy SF Bay Area Shows and Classes. Perform or watch Yeah, yeah, you're pretty funny. But it's one thing to make some of your slightly buzzed Only one block from friends laugh at a party. It's a whole other ballgame to get on a stage in front of an 19th BART audience and do stand-up comedy. To do any kind of live performance, you need to have www.pantheater.com a strong ego and nerves of steel. To do stand-up comedy, you need to be virtually insane. Almost everybody bombs their first time ("bombing" means that you didn't make 'em laugh . in the world of stand-up, that's not good). Learn Stand Up Comedy There's a common misconception that stand-up comics do nothing all day and tell little stories to drunken audiences at night. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Marketing Fundamentals

Comedy and Performance 197g Fall Semester 2017 Tuesday and Thursday 2.00 – 3.20pm Location: LVL 17 Instructor: Louise Peacock Office: JEF 202 Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday 10 – 11. Please contact me for appointments. Contact Info: [email protected] Teaching Assistant or Assistant Instructors: Ashley Steed. Contact Info: [email protected] Jay Lee Contact Info: [email protected] Course Description and Overview This GE course will provide students with an overview and understanding of the history and performance of comedy. Using examples from as far back as Greek Theatre and as current as Modern Family, students will be encouraged to identify and understand the distinctive features, techniques and themes of comedy performance. Through many manifestations including the pantomimes of the Greek and Roman periods, the Commedia dell’Arte of the Renaissance, the flourishing of the circus, the great age of silent comedy in cinema, and the postwar screen era, comedy in performance has evolved in multiple forms as a response to prevailing conditions while maintaining many primary functions, including satire, celebration, and social commentary. The course explores in depth many of the most important and influential periods and differing strains of comic performance, addressing the discipline in terms of creation and execution as envisaged by writers, actors, clowns, comedians, and directors. Learning Objectives 1. To analyze the form and content of comic material across a range of historic periods and to investigate the impact of comedy on audiences 2. To make connections between the comedy of different periods, identifying the social, political and cultural contexts in which the work was created and performed. -

Image to PDF Conversion Tools

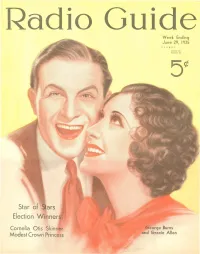

• • Week Ending June 29, 1935 ECAB87 Volume IV Number 36 ¢ Star of ars Election Winners Cornelia Otis Skinner George Burns Modest Crown Princess and Gracie Allen News and Views of the Week Franklin AdvicE'S from "'Jshington indicate a The much·discussed English and German lelevi:!lion further usc of radio by the Chief Ex system~ \\erc discarded here three ye;lrtS ago, D's Big ecutive when other time-honored The RCA gesture unquestionably did much to Stick mcthodo;; of lining up le~islalors fail. strengthen the faith of their own stock and bond holders President Romeve!t look the air and in their properties, but as pointed out by ;l high govern eS13blished a new precedent "hen he acted as hi, o\\n ment radio official, it \\ill he ycars before anyone col messenger ilnd delivered hi'i Honu~ Bill nln mc.... a~e. lech .Ii\·itfends on tele\i~ion. The move proHd ~ucce.... ful frum an Admini~tration I he r.c.c. is trying to determine just what this standllOint. It \\<1"1 lhe fir~l lime Ihe President ha~ had 1l.·lcvi'lnn furore is all about. 'J he Department of Com· to apply the hig ... tick-the Ol>amc one made famoll~ by his men:c has sent Andre W. Cruse, Chief of the Elec illu~triolls rt'!:Hi\e Tl'lld)'. \\ilh modern trimmiI1A", Iric,1I l)ivi~i(Jn, to l:ngland. hanee and Germany, to In making his radio Jddrcss to the country at large. make a first-hand study of the...e denlopments in order Mr. -

CONSERVATIVE COMEDIAN MICHAEL LOFTUS Michael Loftus

CONSERVATIVE COMEDIAN MICHAEL LOFTUS Michael Loftus is a writer, commentator, and standup comedian, and regular guest on Fox News. He has been a headlining talent nationwide for more than twenty years, has written for The George Lopez Show and Charlie Sheen’s Anger Management, and is currently a supervising producer on Kevin Can Wait, now entering its third season. With a voice that steers center right in the political spectrum, Loftus captures in candor and humor the views of those “fly over” states. His podcast, The Loftus Party, dissects the worlds of politics, social media and pop culture, and showcases his rare ability to take complex issues, distill them into simple discussion points, and bring genuine wit and style to the proceedings. In addition to his immense writing talents, his charm and affability on stage have placed him in the upper thresholds of live performers, and he continues to be an audience favorite everywhere he goes. MAGA COUNTRY COMEDY TOUR Everyone likes to say there are no funny conservatives - as if conservatives are incapable of humor. MAGA Country Comedy, presented by The Loftus Party, is here to change all that – once and for all. With a cast of incredibly talented performers who bring years of experience to the stage – this show is undeniably funny. Chad Prather has been described as “the modern-day Will Rogers”. He is a comedian, armchair philosopher, musician, and observational humorist. His social media viral videos are measured in the hundreds of millions. He has made numerous appearances on Fox News, CNN, A&E, and The Blaze. -

COME BACKSTACE with EDDIE CANTOR the ROMANCE of OLSEN and SHUTTA in the Stars • Numbers Handwriting • Dream Omens Your Palm Our Bargain Price

MARCH Posed by JESSICA. DRAGONETIE · COME BACKSTACE WITH EDDIE CANTOR THE ROMANCE OF OLSEN AND SHUTTA in The Stars • Numbers Handwriting • Dream Omens Your Palm Our Bargain Price (Ss.oo Value) ••.•. .• •.... () ..' .. .. •. ,.Aep.O · ~tJs Postage :. ~I tJ IIc Extra .: r tA..,,0"'.., ~f .' PP.~~l,..t-41.s1" · AUTHENTIC UP"TO"DATE P EASY TO READ AND UNDERSTAND When lI·ill the depression end for YOU? Are unhappy canditions CO J11 - ing to a n end? Wha t does thc future hold with regard to money love busin ess, ad vancement? ' , Perh a ps your a nswers lie in the stars-:t he a ncient science of Astrology consulted .by great a nd slll a ll from t lmc ' Illlllemo,:,a l. Your handwriting B .. i ~ hl r c.d art cloth hind i n g. Go ld IS your mll1d on paper!- perh a ps t he a nswer IS 111 Graphology. Study s t a H' I) c d. S i z c your pa lm, the nu mbers r,,;presentcd by your na me, the mea ning of your !ix-7x"1 Y2 . A h o u l 400 drealll s. \"'het her you be ll evc In t hem or not, t hese prognostications are l)agCM ; 5 b ook s in o n e interesti ng, a ut hentic- a nd illex/)ensive. All fi ve of the great fortune telling sciences may now be consulted for what one cost before. GREAT FUN TELLING FORTUNES FOR FRIENDS Eas~ ' to be popular at all social gatherings with t his book of eq ual pro nlinence. -

Jack Benny Program 1953 Sep-Dec.Pdf

-'^:AD-IH TO THE COMMERCIAL Bv JACK BENRY Affi} TAG DI'.iEOTLYBY JACK BENNY IdAS RELEASED FflCM a>)C SOS ANGELES, BECAUSE OF TV PROGRAM BEING SEEN AT 10 P1S-LOS ANGELES TIME, RY ;KU1 016+2-1 0 1 PROGRAM $`1 REVISID SCRIPT 11~7 it /15 IJrOGC/CUSf' AbIERICAN''16SACC~O COMP~ LUCK? STRII~ TfIE JACK SRPIPIY PROGHAM SurIDas, SEPTEMW 13, 1953 CES 4 :00-4 :30 PM PDT (TRANSCRI3ED Sr PT . 9, 1953) KT R1'Y;tJ1 018410 2 THE .TA.CK BF~NNY PROGRAM AMIIdTCPN TOBACCO CO . "SEPTEMBER 13, 1953 (Transcribed September 9, 1953) OPENING COM[uIERCIAL : WILSON : The Jack Benny program . transcribed ar.d presented by Lucky Strike! (Pause) You know, friends . smoking enjoyment is all a matter of taste! And the fact of the matter is . ~ ' COLLINS ; Luckies taste better CHORUS : Cleaner, fresher, smoother COLISNS : Luckies taste better CHCRUS ; Cleaner, fresher, smoother For Lucky Strike means fine tobacco Richer tasting fine tobacco COLLINS ; Luckies taste better CHORUS : Cleaner, fresher, smoother Lucky Strike . Lucky StriKe WITSON : This is Don Wilson . You know, your enjoyment of a I cigarette depends on its taste . That's true, friends . Smoking enjoyment is all a matter of taste . And the fact of the matter,is -- Luckies taste better . cleaner, fresher, smoother . Now there are two mighty good reasons for that . The first one you already know . iS/MFT, :.ucky 1 Strike means fine tobacco . light, naturally mi':d, good-tasting tobacco . And second, Luckies are made to taste better -- made round and firm and fully packed to draw freely and smoke evenly .