Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Assam - a Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 Female Participation in Folk Music of Assam - A Study on Bihugeet in Guwahati (GMA), Assam Palme Borthakur1, Bhaben Ch. Kalita2 1Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India 2Professor, Department of Earth Science, University of Science and Technology, Meghalaya, India Abstract: Songs, instruments and dance- the collaboration of these three ingredients makes the music of any region or society. Folk music is one of the integral facet of culture which also poses all the essentials of music. The instruments used in folk music are divided into four halves-taat (string instruments), aanodha(instruments covered with membrane), Ghana (solid or the musical instruments which struck against one another) and sushir(wind instruments)(Sharma,1996). Out of these four, Ghana and sushirvadyas are being preferred to be played by female artists. Ghana vadyas include instruments like taal,junuka etc. and sushirvadyas include instruments that can be played by blowing air from the mouth like flute,gogona, hkhutuli etc. Women being the most essential part of the society are also involved in the process of shaping up the culture of a region. In the society of Assam since ancient times till date women plays a vital role in the folk music that is bihugeet. At times Assamese women in groups used to celebrate bihu in open spaces or within forest areas or under big trees where entry of men was totally prohibited and during this exclusive celebration the women used to play aforesaid instruments and sing bihu songs describing their life,youth and relation with the environment. -

Nobel's Noble Gifts

Nobel’s Noble Gifts : On October Alfred Bemhard Nobel, 1833 Medicine 8, the Nobel Prize was -.1896, a Swedish chemist awarded to three who invented dynamite in scientists -Mario R. 1866 and developed other Capecchi, Martin J. explosives, suddenly realised Evans and Oliver philanthropy could obliterate Smithies for Physiology/ his disastrous designs when Medicine for their path- he happened to read his own breaking findings in obituary in a paper which biomedical research. termed him "a merchant of Their discoveries death". The paper, however, concerning embryonic carried the obituary of his stem cells and DNA brother, Ludwig by mistake. Alfred Nobel recombination in Nobel who tried to atone for mammals have led to a his sins, turned a do-gooder and bequeathed 94 per cent of Oliver Smithies powerful technology his wealth for awarding prizes to persons or institutions referred to as gene targeting in mice and this is now being for outstanding contributions in their fields of work. The applied to almost all areas of biomedicine, from basic Nobel Foundation announces its awards annually for research to developing new therapies. While Martin J.I persons who had performed outstanding work in the fields Evans is the Director of the School of Biosciences and of Peace, Literature, Physics, Physiology, Medicine and, Professor of Mammalian Genetics of the Cardiff Chemistry from the year 1901. The prize for Economics University in Britain, Mario Capacchi is the Howard was added more than sixty years later. The selection Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and Distinguished process of Nobel Prize awardees is said to be stringent Professor of Human Genetics and Biology of the despite criticisms against such selections for sins of University of Utah and Oliver Smithies is the Excellence omission and commission Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the besides discrimination on the University of North Carolina in the U.S. -

Freebern, Charles L., 1934

THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Freebern, Charles L., 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290233 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6670 FREEBERN, Charles L., 1934- IHE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA/JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS. [Appendix "Pronounciation Tape Recording" available for consultation at University of Arizona Library]. University of Arizona, A. Mus.D., 1969 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CHARLES L. FREEBERN 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • a • 111 THE MUSIC OP INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS by Charles L. Freebern A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA. GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles L, Freebern entitled THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts &• 7?)• as. in? Dissertation Director fca^e After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Connnittee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" _ ^O^tLUA ^ AtrK. -

The Sarangi Family

THE SARANGI FAMILY 1. 1 Classification In the prestigious New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. the sarangi is described as follows : "A bowed chordophone occurring in a number of forms in the Indian subcontinent. It has a waisted body, a wide neck without frets and is usually carved from a single block of wood; in addition to its three or four strings it has one or two sets of sympathetic strings. The sarangi originated as a folk instrument but has been used increasingly in classical music." 1 Whereas this entry consists of only a few lines. the violin family extends to 72 pages. lea ding one to conclude that a comprehensive study of the sarangi has been sorely lacking for a long time. A cryptic description like the one above reveals next to nothing about this major Indian bowed instrument which probably originated at the same time as the violin. It also ignores the fact that the sarangi family comprises the largest number of Indian stringed instruments. What kind of sarangi did the authors visualize when they wrote these lines? Was it the large classical sarangi or one of the many folk types? In which musical context are these instruments used. and how important is the sarangi player? How does one play the sarangi? Who were the famous masters and what did they contribute? Many such questions arise when one talks about the sarangi. A person frnm Romhav-assuminq he is familiar with the sarangi-may have a different 2 picture in mind than someone from Jodhpur or Srinagar. -

The Systems of Digging Ponds by the Ahoms, the Greater Tai Tribe in the North-East India

International Journal of Management Volume 11, Issue 09, September 2020, pp. 657-662. Article ID: IJM_11_09_061 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=9 Journal Impact Factor (2020): 10.1471 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.9.2020.061 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed THE SYSTEMS OF DIGGING PONDS BY THE AHOMS, THE GREATER TAI TRIBE IN THE NORTH-EAST INDIA Dr. Nandita Goswami Nagaon, Assam, India ABSTRACT The meaning of the word ‘Ahom’ in local language of Assam is “Tai People’. The Ahoms are the biggest Tai tribe of North-East India. They reined Assam for six hundred years in the medieval era. They are the descents of Prince Chaolong Su-Ka-Pha who was hailing from the area of Chipchong Panna Dehang of Yunnan Province of China. The course of time they came to be known as the Ahom. They started the process of writing History for the first time in this part of the sub-continent. The period of their rule (1228 AD to 1826 AD) is named as Ahom Yug (Ahom Era). They were very advance in science and technology. The artistic construction and architectural technology of Ahom dynasty was unparalleled and bewildering. The creative and aesthetic designs built hundreds of year ago with unbelievable scientific analysis create inquisitiveness even today. Out of many such creations, one that has long been talked about is the systems of digging voluminous ponds. The most spectacular characteristic of those ponds is that, both during summer and winter season, the water level remains unchanged. -

Documentation on Life and Culture of Deori

DOCUMENTATION ON LIFE AND CULTURE OF DEORI CONDUCTED BY ASSAM INSTITUTE OF RESEARCH FOR TRIBALS AND SCHEDULED CASTES, JAWAHARNAGAR, KHANAPARA, GUWAHATI-781022 1 INTRODUCTION : The word Deori is derived from Sanskrit word Devagrihik. The meaning of Deori is the people who know Deo or Gods or Goddess and worship with devotion “De” means God, “U” means offering and “Ri” means manner or system. Those who know the proceedings of the Puja, and perform sacrifice before the deities are called Deoris. There are four broad divisions amongst the Deoris viz. Dibangias, Tengapanias, Borgoyan and Patorgonga. There divisions are called „Gayan‟ (Khel). Each of the divisions is said to be originated from a particular river or place name. The group settled on the banks of the river Dibang is called Dibangia. The group settled on the banks of river Tengapani is called Tengapania and the group settled on the banks of river Borpani or Bargang is called Borgoyan. The other group living at Patsadiya was known as Patorgonya. But at present existence of this group is not traced. Perhaps due to acculturation and assimilation process the members of the group were amalgamated with other communities. The name Borgoyan is said to have originated from the great number of households (Jakhela) in the village. It is said the village had one hundred and eighty households hence Bargaon / Borgand or Bargonya. Although the Deoris of present generation refuse to accept the prevailing notion that Deoris were one of the divisions of Chutiyas, and they were only priests of the Chutiya kings, yet the linkage of Chutiyas with the Deoris cannot be underestimated. -

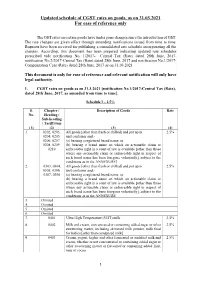

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

Other String Instruments Catalogue

. Product Catalogue for Other Strings Instruments Contents: 4 Strings Violin…………………………………………………………………………………...1 5 Strings Violin……………………...…………………………………………………………...2 Bulbul Tarang....…………………...…………………………………………………………...3 Classical Veena...…….………………………………………………………………………...4 Dilruba.…………………………………………………………………….…………………..5 Dotara……...……………………...…………………………………………………………..6 Egyptian Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………...7 Ektara..…………….………………………………………………………………………...8 Esraaj………………………………………………………………………………………10 Gents Tanpura..………………...…………………………………………………………11 Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………..............12 Kamanche……….……………………………………………………………………….13 Kamaicha……..…………………………………………………………………………14 Ladies Tanpura………………………………………………………………………...15 Lute……………………...……………………………………………………………..16 Mandolin…………………...…………………………………………………………17 Rabab……….………………………………………………………………………..18 Saarangi……………………………………………………………………………..22 Saraswati Veena………...………………………………………………………….23 Sarinda……………...………………………………………………………….......24 Sarod…….………………………………………………………………………...25 Santoor……………………………………………………………………………26 Soprano………………...………………………………………………………...27 Sor Duang……………………………………………………………………….28 Surbahar……………...…………………………………………………………29 Swarmandal……………….……………………………………………………30 Taus…………………………………………………………………………….31 Calcutta Musical Depot 28C, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road, Kolkata-700 025, West Bengal, India Ph:+91-33-2455-4184 (O) Mobile:+91-9830752310 (M) 24/7:+91-9830066661 (M) Email: [email protected] Web: www.calmusical.com /calmusical /calmusical 1 4 Strings Violin SKU: CMD/4SV/1600 -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

UNIT 3 PERFORMING ART PRACTICAL Notes STRUCTURE

Performing Art Practical UNIT 3 PERFORMING ART PRACTICAL Notes STRUCTURE 3.0 Introduction 3.1 Learning Objectives 3.2 Elements in different performing arts 3.2.1 Music 3.2.1.1Vocal 3.2.1.2Instrumental 3.2.2 Dance 3.2.2.1Folk 3.2.2.2 Classical 3.2.2.3 Creative 3.2.3 Theatre 3.2.3.1 Folk Theatre 3.2.4 Puppetry 3.2.5 Significance of Regional Art Forms 3.3 Planning and Preparation of any Performing Art 3.3.1 Planning 3.3.2 Preparation 3.3.3 Tips for Presentation 3.4 Making a Folder of covering practical activities 3.5 Let us Sum up 3.6 Answers to Check Your Progress 3.7 Suggested Readings and References 3.8 Unit-End Exercises 3.0 INTRODUCTION In the previous chapter you have learned about Visual Arts and Craft. The chapter gives you the knowledge about different aspects of Visual Arts and Craft. It 60 Diploma in Elementary Education (D.El.Ed) Performing Art Practical describes fundamentals of Art, experimentation with different materials and Exploration and Experimentation with different Methods of Visual Arts and Crafts. Apt implementation by teachers will give ample opportunity for children to Notes explore and experiment .It will enhance the creativity of the child and also help them to explore and enjoy in the immediate environment. As Art figures in almost every walk of life Art and India are almost synonymous. Right from birth singing the soothing lullaby to the child, enacting tales of valor and courage in schools and community celebration from the epics – The ‘Mahabharata’ and The ‘Ramayana’, or Panchatantra we are connected to art.