Documentation on Life and Culture of Deori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta As Assam slowly recovers from the double whammy of COVID-19 pandemic and floods, I utilized every little opportunity to visit instrument makers living in the interior villages of Assam. My first visit was made to a Satra (Neo-vaishnavite monastery) by the name of Balipukhuri Satra on the outskirts of Tezpur (Sonitpur district), the cultural capital of Assam. There in the Satra, the family introduced me to three hundred years old folk instruments. A Sarinda, which is an archaic bowed string instrument, turns out to be one of their most prized possessions. Nobody in the family is an instrument maker, however, their ancestors had received the musical instruments from an Ahom king almost three hundred years back. The Sarinda remains in a dilapidated condition, with not much interest given to its restoration. Thus, the sole purpose that the instrument is serving is ornamentation. Fig 1: The remains of a Sarinda at Balipukhuri Satra The week after that was my visit to a village in Puranigudam, situated in Nagaon district of Assam. Two worshippers of Lord Shiva, Mr. Golap Bora and Mr. Prafulla Das, told tales of Assamese folk instruments they make and serenaded me with folk songs of Assam. Just before lunchtime, I visited Mr. Kaliram Bora and he helped me explore a range of Assamese instruments, the most interesting among which is the Kali. The Kali is a brass musical instrument. In addition to making instruments, Kaliram Bora is a well-known teacher of the Kali and has been working with the National Academy of Music, Dance and Drama’s Guru-shishya Parampara system of schools to imbibe education in Kali to select students of Assam. -

The Systems of Digging Ponds by the Ahoms, the Greater Tai Tribe in the North-East India

International Journal of Management Volume 11, Issue 09, September 2020, pp. 657-662. Article ID: IJM_11_09_061 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=9 Journal Impact Factor (2020): 10.1471 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.9.2020.061 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed THE SYSTEMS OF DIGGING PONDS BY THE AHOMS, THE GREATER TAI TRIBE IN THE NORTH-EAST INDIA Dr. Nandita Goswami Nagaon, Assam, India ABSTRACT The meaning of the word ‘Ahom’ in local language of Assam is “Tai People’. The Ahoms are the biggest Tai tribe of North-East India. They reined Assam for six hundred years in the medieval era. They are the descents of Prince Chaolong Su-Ka-Pha who was hailing from the area of Chipchong Panna Dehang of Yunnan Province of China. The course of time they came to be known as the Ahom. They started the process of writing History for the first time in this part of the sub-continent. The period of their rule (1228 AD to 1826 AD) is named as Ahom Yug (Ahom Era). They were very advance in science and technology. The artistic construction and architectural technology of Ahom dynasty was unparalleled and bewildering. The creative and aesthetic designs built hundreds of year ago with unbelievable scientific analysis create inquisitiveness even today. Out of many such creations, one that has long been talked about is the systems of digging voluminous ponds. The most spectacular characteristic of those ponds is that, both during summer and winter season, the water level remains unchanged. -

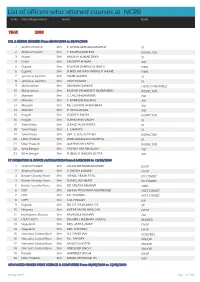

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Folk Culture of Assam : Meaning and Importance 36-54

GHT S6 02(M) Exam Codes: HTM6B CULTURAL HISTORY OF ASSAM SEMESTER - VI HISTORY BLOCK - 1 KRISHNA KANTA HANDIQUI STATE OPEN UNIVERSITY Subject Expert 1. Dr. Sunil Pravan Baruah, Retd. Principal, B.Barooah College, Guwahati 2. Dr. Gajendra Adhikari, Principal, D.K.Girls’ College, Mirza 3. Dr. Maushumi Dutta Pathak, HOD, History, Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati Course Co-ordinator : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, Asst. Prof. (KKHSOU) SLM Preparation Team UNITS CONTRIBUTORS 1 & 2 Dr. Mamoni Sarma, L.C.B. College 3 Dr. Dhanmoni Kalita, Bijni College 4 & 5 Mitali Kalita, Research Scholar, G.U 6 Dr. Sanghamitra Sarma Editorial Team Content Editing: Dr Moushumi Dutta Pathak, Department of History, Arya Vidyapeeth College Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, Department of History, KKHSOU Structure, Format & Graphics : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, KKHSOU December , 2019 © Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. This Self Learning Material (SLM) of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike4.0 License (international): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Printed and published by Registrar on behalf of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. Head Office : Patgaon, Rani Gate, Guwahati-781017 City Office : Housefed Complex, Dispur, Guwahati-781 006; Web: www.kkhsou.in The University acknowledges with thanks the financial support provided by the Distance Education Council, New Delhi, for the preparation of this study material. BACHELOR OF ARTS CULTURAL HISTORY OF ASSAM DETAILED SYLLABUS BLOCK - 1 PAGES UNIT 1 : Assamese Culture and Its Implication 5-23 Definition of Culture; Legacy of Assamese Culture; Interpretations and Problems UNIT 2 : Assamese Culture and Its Features 24-35 Assamese Culture and its features: Assimilation and Syncretism UNIT 3 : Folk Culture of Assam : Meaning and Importance 36-54 Meaning and Definition of Folk Culture; Relation to the Society; Tribal Culture vs. -

Bihu Festival: Dance of the Goddesses

Vol-7 Issue-3 2021 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 BIHU FESTIVAL: DANCE OF THE GODDESSES SUWANEE GOSWAMI* & ERIC SORENG**, Ph. D. *Research Scholar Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi **Associate Professor Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi Abstract The amorous dance of the Goddesses—Kolimoti, Seuti and Malati—has given birth to the Bihu festival in Assam which has instinctively ingrained the joy of dance and music in every Assamese woman and man in every form of festivities in and beyond Bohag Bihu. The mythic origin of Bohag Bihu shows diversion from the blood sacrifice to the Goddesses to the repetition of and participation in the dance of the Goddesses. In the archaic spirituality of Assam, women dance repeating the mythic acts of the Goddesses and men partake in the joy as nature blooms and humankind prosper in the amorous state of the Goddesses. The paper presents interpretation of one of the myths of the origin of the Bihu festival. “Man is obliged to return to the actions of his Ancestor, either to confront or else repeat them; in short, never to forget them, whatever way he may choose to perform this regressus ad originem” (Eliade, 1959). Humankind has evolved as a race from the primitive to the modern state of being with numerous breakthroughs and developments in various spheres of activity since the twilight of civilization. However, even in this age of technology and materialism, the modern mentality continues to display traces of mythic traits, in spite of the mutations in religious and cultural history. To reinstate the words of Jung: “…every civilized human being, whatever his conscious development, is an archaic man at the deeper levels of his psyche” (Jacobi, 1953, p. -

Bohag Bihu and Other Spring Festivals Among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam: an Understanding of Their Present Status

Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University ISSN: 1007-1172 Bohag Bihu and other Spring Festivals among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam: An Understanding of their Present Status ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Submitted by Dr. Montu Chetia Department of History, Kampur College, Nagaon, Assam-782426 Gmail ID: [email protected] Phone: 9101093556 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Volume 16, Issue 11, November - 2020 https://shjtdxxb-e.cn/ Page No: 319 Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University ISSN: 1007-1172 Bohag Bihu and other Spring Festivals among the People of Lakhimpur District of Assam : An Understanding of their Present Status. Dr Montu Chetia ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Bihu is a national festival of Assam celebrated by all sections of the society irrespective of caste, creed and religion. The Bihu is the identity of Assamese people in all over the country. It is also the symbol of unity among the people of the state. There are three kinds of Bihu generally observed in Assam- Bohag Bihu or Rongali Bihu, Magh Bihu or Bhogali Bihu and Kati Bihu or Kongali Bihu. Every Bihu has its own features and characteristics which have enriched the cultural prosperity of Assam as well as the whole north eastern region . On the other hand although Bihu is the national festival of Assam yet it varies in form from place to place which have developed the cultural diversity of the state . Being a part of the state people of Lakhimpur district observe all these Bihus in their customary and ritualistic manner. Along with the Bihus some other spring festivals are also observed in Lakhimpur district with great enthusiasm. The present paper has an attempt to study the nature of these festivals of Lakhimpur district which are primarily observed in the spring season. -

Chapter Iii the Bihu Festival As a Cultural Expression: Sacred

CHAPTER III THE BIHU FESTIVAL AS A CULTURAL EXPRESSION: SACRED - SECULAR CONTINUUM AND FUNCTIONALITY Emanating from its multi ethnic, multi religious and multi linguistic matrix, Assam is endowed with varied cultural traditions practiced by the respective communities including : Mising, Tiwa, Moran, Kachari, Bodo, Dimasa, among others as described earlier, which are spread over areas in upper, middle and lower Assam. All the communities across the state celebrate spring-time festival following their own traditions and customs. The word ‘Bihu’ has become synonymous with all spring - time festivals prevalent in Assam. There are both commonalities and diversity within the Bihu. 3.1 The Bihu: Three Varieties Bihu, the most colourful and widely celebrated festival of Assam is of three varieties (i) Magh or Bhogali Bihu, (ii) Bohag or Rongali Bihu, (iii) Kati or Kongali Bihu. “Bihus constitute a sort of pattern, a ritual and a festival complex, covering the annual life cycle of the peasantry” (Goswami, 2003: 7). Bohag Bihu (Rongali Bihu) Bohagor rongali Bihu, the festival of celebration commences in mid-April. It starts with garu Bihu in which cattle are worshipped observing various rituals. It is followed by manuh Bihu and gosain Bihu. The primary attraction of Bohag Bihu is the music and dance part associated with the festival. It is classified into husori which is performed by male dancers, gabharu Bihu which is performed by female dancers and deka gabharu Bihu in which both male and female participate. All the performances were held in agricultural fields in the past times. However, today, it is mostly observed and performed on the proscenium stage in the form of a large community spectacle which also includes various competitions. -

Paragon of Musical Fiesta in Assam Richa Gogoi, Jyoti Senapati Research Scholar, Department of MIL, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume 4 Issue 6, September-October 2020 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470 Paragon of Musical Fiesta in Assam Richa Gogoi, Jyoti Senapati Research Scholar, Department of MIL, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India ABSTRACT How to cite this paper: Richa Gogoi | Jyoti Assam is a land where great many tribes commingle. Traces of several ethnic Senapati "Paragon of Musical Fiesta in groups like Negrito, Austric, Alpine, Aryan, Dravidian and Vedic Aryans are Assam" Published in residing in Assam. Few tribes of Assam are Ahom, Karbi, Boro, Tiwa, Dimasa, International Journal Deori, Mising and so on. These tribes have a rich heritage associated with with of Trend in Scientific music, art and culture. However music and instruments are the nucleus of Research and entertainment for these tribes. An air of melancholy surrounds the valleys of Development Assam as proper study of the tribal music and instruments haven’t been laid (ijtsrd), ISSN: 2456- hold of. This paper endeavours the musical interest of the many tribes found 6470, Volume-4 | IJTSRD33351 in Assam along with their musical instruments. Issue-6, October 2020, pp.287-291, URL: KEYWORDS: Assam, Music, Culture, Tribes, Instruments www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd33351.pdf Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by /4.0) 1. INTRODUCTION The state of Assam in the Northeast of India is an abode to A description of the musical instruments traditionally used cultural amalgamation. -

Agricultural Folk Songs of Assam

e-publication AGRICULTURAL FOLK SONGS OF ASSAM A. K. Bhalerao Bagish Kumar A. K. Singha P. C. Jat R. Bordoloi A. M. Pasweth Bidyut C.Deka ICAR-ATARI , Zone-III Indian Council of Agricultural Research Umiam, Meghalaya- 793103 1 e-publication AGRICULTURAL FOLK SONGS OF ASSAM A. K. Bhalerao Bagish Kumar A. K. Singha P. C. Jat R. Bordoloi A. M. Pasweth Bidyut C. Deka ICAR-ATARI , Zone-III Indian Council of Agricultural Research 2 Umiam, Meghalaya- 793103 FORWARD The ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research institute, Zone-III with its headquarters at Umiam, Meghalaya is the nodal institution for monitoring the extension activities conducted by the Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) in North East Region, which comprises of eight states, namely Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura. All these states have the tribal population which gives them the unique identity as compared to the other part of the country. This peculiarity is due to the traditional wealth conserved by the people of this region from ancestors through oral traditions. Folk songs in relation of agriculture are one of the traditional assets for this region. These songs describe the different aspects of nature in general and agriculture in particular for understanding them in a comprehensive way. It simply shows the close liaison of the native people with the natural phenomenon. I appreciate the effort and hardship of the KVK staffs in general and editors of this publication in particular for bringing out such a useful document for the benefit of all the stakeholders working for the prosperity of indigenous people. -

Popular Folk Musical Instruments an Assamese Folk Festival Instruments by Prof

D’source 1 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Popular Folk Musical Instruments An Assamese Folk Festival Instruments by Prof. Ravi Mokashi Punekar and Shri. Dijen Gogoi DoD, IIT Guwahati Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/popular-folk-musi- cal-instruments 1. Introduction 2. Folk Musical Instruments 3. The Making 4. Contact Details D’source 2 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Introduction Popular Folk Musical Instruments Bihu, an Assamese folk festival celebrates the jubilant three seasons that marks the beginning, middle and end An Assamese Folk Festival Instruments of a year in Assamese calendar. Rongali or Bohag, Kati or Kongali and Boghali or Magh Bihu, viz are celebrated at different times in a year and each one of them has a significant role in telling stories of the agrarian community. by The folk songs assume great significance since they reflect the correct sentiment amongst the natives and fur- Prof. Ravi Mokashi Punekar and Shri. Dijen Gogoi ther narrate the significance of the season. DoD, IIT Guwahati Of the three bihu festivals which are secular and non religious, the Bohag Bihu ushers in the period of greatest enjoyment and marks the arrival of spring. The Folk songs associated with Bohag bihu are called Bihu Geets or Bihu Songs. The sights of “mukoli bihus” are often during the month of April - the month celebrated by all age Source: groups as the arrival of spring. Romance and songs of merriment occupies a central place amongst the young http://www.dsource.in/resource/popular-folk-musi- boys and girls as they get together in open spaces dancing and singing to the tunes of Bihu. -

Art and Culture of Majuli: History and Growth

Chapter II Art and Culture of Majuli: History and Growth 2.1 Introduction Majuli a pilgrimage island of Assam is distinguished for its geography, culture and primarily a place where Vaisnavism has prospered since fifteenth century (plate-2.1). The island is a paradise of biodiversity of flora and fauna, which is nurtured by vast Brahmaputra River. Majuli is celebrated as the world’s biggest river island nestles in the lap of the mighty Brahmaputra (plate-2.2) and also the place of numerous Satra Institutions (Vaisnavite monasteries), in which some of the Satra celebrated as the most legendary Satras of the Assam, caring the heritage of socio-religious culture, and rich traditions of various art and literature, signifies it from the other places of Assam (plate-2.3, 2.4). Majuli has its own inherent features, due to its topographical conditions the island has not been much coupled with the mainland and creates isolated water bounded populated zone. The inhabitants of the island had no often interaction with the main stream society during the Middle Ages. Presently Majuli is a subdivision of the Jorhat Dristirct of Assam, (plate- 2.5, 2.6) the old stream of Brahmaputra namely the Luit or Luhit Suti with a thin stream of water flows north of the island, its eastern stream is called Kherkatiya Suti and the western stream is known as Suvansiri (Subansiri), and in the south of the island main Brahmaputra flows which was earlier the course of the Dihing and Dikhow combined.(Nath: 2009) Therefore the east and the west ends of the island are pointed as the junction and amalgamation respectively of the two channels of the same great river.