The Sarangi Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company https://www.indiamart.com/rikhirammusicalinstruments/ Manufacturer of sarangi, dholak and teak wood sitar. About Us Indian instruments belong to a tradition dipped in antiquity. It dates back to the Veena of Saraswati, Bansuri of Krishna and Damru of Shiva, corresponding to modern classifications of musical instruments under string, wind & percussions respectively. The journey of 'Rikhi Ram Musical Instrument Mfg.Co' started with founder Late Pt. Rikhi Ram, who was a great musicians and one of the best known musical instrument maker. Pt. Rikhi Ram's father Pt. Gobind Ram was also a musician and had inclinations towards making musical instruments and so manufacturing of musical instruments started in the family 85 years ago. Pt. Rikhi Ram learnt sitar playing from eminent musician Abdul Harim Poonchwala. Late Pt. Bishan Dass followed in his father's footsteps and started learning sitar at a very tender age under the guidance and supervision of his father. Later, he became a disciple of world renowed sitar maestro Pt. Ravi Shankar. He also worked in the maintainance cell of A.I.R. During his tenor at A.I.R he got associated with great musicians like Ustad Allauddin Khan, Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pt.Ravi Shankar and many others. From these great Ustads Bishan learnt that the primal value of a good instrument was its tonal quality. They would often discuss these aspects of an instrument and give him useful hints. "This extra interest fired my imagination and aroused in me the urge to produce quality instruments for the maestros" says Late Pt. -

Freebern, Charles L., 1934

THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Freebern, Charles L., 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290233 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6670 FREEBERN, Charles L., 1934- IHE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA/JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS. [Appendix "Pronounciation Tape Recording" available for consultation at University of Arizona Library]. University of Arizona, A. Mus.D., 1969 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CHARLES L. FREEBERN 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • a • 111 THE MUSIC OP INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS by Charles L. Freebern A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA. GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles L, Freebern entitled THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts &• 7?)• as. in? Dissertation Director fca^e After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Connnittee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" _ ^O^tLUA ^ AtrK. -

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta As Assam slowly recovers from the double whammy of COVID-19 pandemic and floods, I utilized every little opportunity to visit instrument makers living in the interior villages of Assam. My first visit was made to a Satra (Neo-vaishnavite monastery) by the name of Balipukhuri Satra on the outskirts of Tezpur (Sonitpur district), the cultural capital of Assam. There in the Satra, the family introduced me to three hundred years old folk instruments. A Sarinda, which is an archaic bowed string instrument, turns out to be one of their most prized possessions. Nobody in the family is an instrument maker, however, their ancestors had received the musical instruments from an Ahom king almost three hundred years back. The Sarinda remains in a dilapidated condition, with not much interest given to its restoration. Thus, the sole purpose that the instrument is serving is ornamentation. Fig 1: The remains of a Sarinda at Balipukhuri Satra The week after that was my visit to a village in Puranigudam, situated in Nagaon district of Assam. Two worshippers of Lord Shiva, Mr. Golap Bora and Mr. Prafulla Das, told tales of Assamese folk instruments they make and serenaded me with folk songs of Assam. Just before lunchtime, I visited Mr. Kaliram Bora and he helped me explore a range of Assamese instruments, the most interesting among which is the Kali. The Kali is a brass musical instrument. In addition to making instruments, Kaliram Bora is a well-known teacher of the Kali and has been working with the National Academy of Music, Dance and Drama’s Guru-shishya Parampara system of schools to imbibe education in Kali to select students of Assam. -

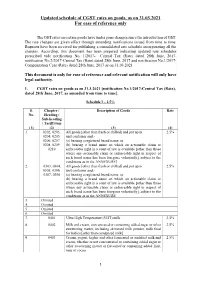

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

Indian Music Instruments Sarangi Sitar Sitar Is of the Most Popular Music

Indian Music Instruments Sarangi Sitar Sitar is of the most popular music instruments of North India. The Sitar has a long neck with twenty metal frets and six to seven main cords. Below the frets of Sitar are thirteen sympathetic strings which are tuned to the notes of the Raga. A gourd, which acts as a resonator for the strings is at the lower end of the neck of the Sitar. The frets are moved up and down to adjust the notes. Some famous Sitar players are Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pt. Ravishankar, Ustad Imrat Khan, Ustad Abdul Halim Zaffar Khan, Ustad Rais Khan and Pt Debu Chowdhury. Sarod Sarod has a small wooden body covered with skin and a fingerboard that is covered with steel. Sarod does not have a fret and has twenty-five strings of which fifteen are sympathetic strings. A metal gourd acts as a resonator. The strings are plucked with a triangular plectrum. Some notable exponents of Sarod are Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, Pt. Buddhadev Das Gupta, Zarin Daruwalla and Brij Narayan. Sarangi Sarangi is one of the most popular and oldest bowed instruments in India. The body of Sarangi is hollow and made of teak wood adorned with ivory inlays. Sarangi has forty strings of which thirty seven are sympathetic. The Sarangi is held in a vertical position and played with a bow. To play the Sarangi one has to press the fingernails of the left hand against the strings. Famous Sarangi maestros are Rehman Bakhs, Pt Ram Narayan, Ghulam Sabir and Ustad Sultan Khan. -

Other String Instruments Catalogue

. Product Catalogue for Other Strings Instruments Contents: 4 Strings Violin…………………………………………………………………………………...1 5 Strings Violin……………………...…………………………………………………………...2 Bulbul Tarang....…………………...…………………………………………………………...3 Classical Veena...…….………………………………………………………………………...4 Dilruba.…………………………………………………………………….…………………..5 Dotara……...……………………...…………………………………………………………..6 Egyptian Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………...7 Ektara..…………….………………………………………………………………………...8 Esraaj………………………………………………………………………………………10 Gents Tanpura..………………...…………………………………………………………11 Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………..............12 Kamanche……….……………………………………………………………………….13 Kamaicha……..…………………………………………………………………………14 Ladies Tanpura………………………………………………………………………...15 Lute……………………...……………………………………………………………..16 Mandolin…………………...…………………………………………………………17 Rabab……….………………………………………………………………………..18 Saarangi……………………………………………………………………………..22 Saraswati Veena………...………………………………………………………….23 Sarinda……………...………………………………………………………….......24 Sarod…….………………………………………………………………………...25 Santoor……………………………………………………………………………26 Soprano………………...………………………………………………………...27 Sor Duang……………………………………………………………………….28 Surbahar……………...…………………………………………………………29 Swarmandal……………….……………………………………………………30 Taus…………………………………………………………………………….31 Calcutta Musical Depot 28C, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road, Kolkata-700 025, West Bengal, India Ph:+91-33-2455-4184 (O) Mobile:+91-9830752310 (M) 24/7:+91-9830066661 (M) Email: [email protected] Web: www.calmusical.com /calmusical /calmusical 1 4 Strings Violin SKU: CMD/4SV/1600 -

Folk Instruments of Punjab

Folk Instruments of Punjab By Inderpreet Kaur Folk Instruments of Punjab Algoza Gharha Bugchu Kato Chimta Sapp Dilruba Gagar Dhadd Ektara Dhol Tumbi Khartal Sarangi Alghoza is a pair of woodwind instruments adopted by Punjabi, Sindhi, Kutchi, Rajasthani and Baloch folk musicians. It is also called Mattiyan ,Jōrhi, Pāwā Jōrhī, Do Nālī, Donāl, Girāw, Satārā or Nagōze. Bugchu (Punjabi: ਬੁਘਚੂ) is a traditional musical instrument native to the Punjab region. It is used in various cultural activities like folk music and folk dances such as bhangra, Malwai Giddha etc. It is a simple but unique instrument made of wood. Its shape is much similar to damru, an Indian musical instrument. Chimta (Punjabi: ਚਚਮਟਾ This instrument is often used in popular Punjabi folk songs, Bhangra music and the Sikh religious music known as Gurbani Kirtan. Dilruba (Punjabi: ਚਿਲਰੱਬਾ; It is a relatively young instrument, being only about 300 years old. The Dilruba (translated as robber of the heart) is found in North India, primarily Punjab, where it is used in Gurmat Sangeet and Hindustani classical music and in West Bengal. Dhadd (Punjabi: ਢੱਡ), also spelled as Dhad or Dhadh is an hourglass-shaped traditional musical instrument native to Punjab that is mainly used by the Dhadi singers. It is also used by other folk singers of the region Dhol (Hindi: ढोल, Punjabi: ਢੋਲ, can refer to any one of a number of similar types of double-headed drum widely used, with regional variations, throughout the Indian subcontinent. Its range of distribution in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan primarily includes northern areas such as the Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Kashmir, Sindh, Assam Valley Gagar (Punjabi: ਗਾਗਰ, pronounced: gāger), a metal pitcher used to store water in earlier days, is also used as a musical instrument in number of Punjabi folk songs and dances. -

Musical Instruments of North India 5.1 Do You Know

Musical instruments of North India 5.1 Do you know Description Image Source Sarangi is the only instrument which comes in closest proximity to the human voice and therefore it is very popular among the singers as an accompanying instrument in hindustani classical music. Pakhawaj is the only percussion instrument to accompany the dhrupad style of singing. Bansuri or flute is a simple bamboo tube of a uniform bore. The primary function of tabla is to mentain the metric cycle in which the compositions are set. Tanpura is an instrumenused in both north and south Indian classical music. 5.2 Glossary Staring Related Term Definition Character Term Membranophones, instruments in which sound is A Avanadha produced by a membrane, stretched over an opening. B Bansuri A bamboo transverse flute of north India. D Dand The finger board. G Ghan Idiophones; percussion Instruments. A stringed musical instrument with a fretted finger board Guitar played by plucking or strumming with the fingers or a plectrum. H Harmonium A free reed aero phone which has a keyboard. K Khunti Tuning pegs. P Pakhawaj A percussion instrument used as an accompaniment. A large plucked string instrument used in R RudraVeena HindustaniClassical music. Aero phones, wind instruments in which sound is S Sushir produced by the vibration of air. A plucked string instrument used in HindustaniClassical Sitar music. A stringed musical instrument used in Sarod HindustaniClassical music. A trapezoid shaped string musical instrument played with Santoor two wooden sticks. A bowing stringed instrument used in Sarangi HindustaniClassical music. A wind instrument particularly played on auspicious Shehnai occasions like weddings. -

South Asian Dance & Music Mapping Study

South Asian Dance & Music Mapping Study - APPENDICES Commissioned by: Arts Council England April 2020 December 2020 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendices to Report Contents Appendices Appendix 1 Consultation List 3 Appendix 2 Market Analysis 17 Appendix 3 Desk Research Literature Review 77 Appendix 4 Excel Mapping Docs with Macros (attached separately) Appendix 4a Excel Mapping Docs without Macros (attached separately) Appendix 5 Sector Survey Findings 121 December 2020 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendix 1: Consultation List Appendix 1 – Consultation List In total 103 South Asian musicians and/or dancers and stakeholders were consulted through one to one consultations and/or a series of round table sector discussions. South Asian Dance & Music: Consultation List – One to One Depth Interviews Name Organisation / Title 1. Seetal Kaur ACE Relationship Manager (Dance), Midlands & SA Dancer https://www.curveonline.co.uk/news/meet-the-artist-seetal-kaur/ 2. Mithila Sarma ACE Relationship Manager (Music) & SA Musician https://prsfoundation.com/grantees/women-make-music-mithila-sarma/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b061c3t4 3. Jan De Schynkel ACE Relationship Manager, Dance & Project Lead 4. Joe Shaw ACE Senior Officer, Policy & Research & Project Team 5. Victoria Merriman ACE Relationship Manager; Children Young People and Learning / Music Education 6. Laura Evans Relationship Manager, Dance 7. Raúl S-V Calderón Relationship Manager 8. Gabby Chelmicka ACE Relationship Manager, Music December 2020 3 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendix 1: Consultation List Name Organisation / Title 9. Amelia Henderson ACE Relationship Manager, Combined Arts 10. Thomas Wildish ACE Relationship Manager, Theatre 11. -

T>HE JOURNAL MUSIC ACADEMY

T>HE JOURNAL OF Y < r f . MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY IrGHTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE ' AND ART OF MUSIC XXXVIII 1967 Part.' I-IV ir w > \ dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, ^n- the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there L ^ Narada ! ” ) EDITED BY v. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1967 PUBLISHED BY 1US1C ACADEMY, MADRAS a to to 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD, MADRAS-14 bscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. X \ \ !• ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES \ COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page i BaCk (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 99 20 .. 11. BaCk (Do.) 30 *# ” J6 INSIDE PAGES: i 1st page (after Cover) 99 18 io Other pages (eaCh) 99 15 .. 9 PreferenCe will be given (o advertisers of musiCal ® instruments and books and other artistic wares. V Special positions and speCial rates on appliCation. t NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Ragb Editor, Journal of the MusiC ACademy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of musiC and dance are accepte publication on the understanding that they are Contributed to the Journal of the MusiC ACademy. f. AIT manuscripts should be legibly written or preferabl; written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be sigoed by the writer (giving his address in full). I The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for tb expressed by individual contributors. AH books, advertisement moneys and cheques du> intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V, B Editor. CONTENTS Page T XLth Madras MusiC Conference, 1966 OffiCial Report .. -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :20/12/2019

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :20/12/2019 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 ARBA/0000038/2019 FORUM PROJECTS PVT. LTD. AMIT PRASAD BOSE / / VS VS () BERHAMPUR DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY // 2 BLAPL/0011046/2019 DHANU @ DHANESWAR PURTY B.N.MAHAPATRA ROURKELA GRPS. /72 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0011047/2019 SAROJ KUMAR DASH ARIJEET MISHRA JEYPORE MAHILA /61 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0011048/2019 KASHINATH MAHANTA L.BHUYAN TELKOI /182 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0011049/2019 KORADA BALAJI KRISHNA @ K.BALAJI KRISHNAMANORANJAN PADHY NANDAPUR /76 /2016 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0011050/2019 BIBHUTI BHUSAN MALLICK S.C.ACHARYA KUJANGA /199 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0011051/2019 AFTAB ALAM KHAN SUBHASHIS MISHRA BHUBANESWAR VIGILANCE /64 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA, VIG. // 8 BLAPL/0011052/2019 RUPENDRA BEHERA JYOTIRMAYA SAHOO / /0 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0011053/2019 GOPABANDHU SUNA SURYAKANTA DWIBEDI JHARBANDH /74 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0011054/2019 MD.INZEMAM @ ROCKY PARTHA SARATHI NAYAK COLLIERY /418 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0011055/2019 BELIA@ SUSANTA KUMAR MAJHI JITENDRA SAMANTARAY KHURDA P.S. /264 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/63 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :20/12/2019 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0011056/2019 BIJAY KUMAR MALLIK AMULYA RATNA PANDA MANGALPUR /365