A Set of Performance Practice Instructions for a Western Flautist Presenting Japanese and Indian Inspired Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network Ot Create Concerto Pour Flute Et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute Et Piano

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2016 Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network ot Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano Kelly A. Collier University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Education Commons, and the Music Commons Repository Citation Collier, Kelly A., "Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network to Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2856. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10083130 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANDRÉ JOLIVET’S FUSION: MAGICAL MUSIC, CONVENTIONAL LYRICISM, AND JAPANESE INFLUENCES NETWORK TO CREATE CONCERTO POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO AND SONATE POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO By Kelly A. Collier Bachelor of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1999 Master of Music California State University, Long Beach 2001 Master of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2016 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2016 Copyright 2016 Kelly A. -

Prepared Objects, Compositions That Use Them, and the Resulting Sound Dr

Prepared objects, compositions that use them, and the resulting sound Dr. Stacey Lee Russell Under/On Aluminum foil 1. Beste, Incontro Concertante Buzzing, rattling 2. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes the keys Cigarette 1. Zwaanenburg, Solo for Prepared Flute Buzzing, rattling paper 2. Szigeti, That’s for You for 3 flutes 3. Matuz, “Studium 6” from 6 Studii per flauto solo 4. Gyӧngyӧssy, “VII” from Pearls Cork 1. Ittzés, “A Most International Flute Festival” Cork is used to wedge specific ring keys into closed positions. Mimics Bansuri, Shakuhachi, Dizi, Ney, Kaval, Didgeridoo, Tilinka, etc. Plastic 1. Bossero, Silentium Nostrum “Inside a plastic bag like a corpse,” Crease sound, mimic “continuous sea marine crackling sensation.” Plastic bag 1. Sasaki, Danpen Rensa II Buzzing, rattling Rice paper 1. Kim, Tchong Buzzing, rattling Thimbles 1. Kubisch, “It’s so touchy” from Emergency Scratching, metallic sounds Solos Inside Beads 1. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes Overtone series, intonation, beating the tube Buzzers 1. Brockshus, “III” from Greytudes Distortion of sound Cork 1. Matuz, “Studium 1” from 6 Studii per flauto Overtone series, note sound solo octave lower than written 2. Eӧtvӧs, Windsequenzen 3. Zwaanenburg, Solo for Prepared Flute 4. Matuz, “Studium 5” from 6 Studii per flauto solo 5. Fonville, Music for Sarah 6. Gyӧngyӧssy, “III” from Pearls 7. Gyӧngyӧssy, “VI” from Pearls Darts 1. Brockshus, “II” from Greytudes Beating, interference tones Erasers & 1. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes Overtone series, intonation, Earplugs beating Plastic squeaky 1. Kubisch, “Variation on a classical theme” Strident, acute sound toy sausage from Emergency Solos Siren 1. Bossero, Silentium Nostrum Marine signaling, turbine spins/whistles Talkbox 1.Krüeger, Komm her, Sternschnuppe Talkbox tube is hooked up to the footjoint, fed by pre- recorded tape or live synthesizer sounds © Copyright by Stacey Lee Russell, 2019 www.staceyleerussell.com [email protected] x.stacey.russell Towel 1. -

The World Atlas of Musical Instruments

Musik_001-004_GB 15.03.2012 16:33 Uhr Seite 3 (5. Farbe Textschwarz Auszug) The World Atlas of Musical Instruments Illustrations Anton Radevsky Text Bozhidar Abrashev & Vladimir Gadjev Design Krassimira Despotova 8 THE CLASSIFICATION OF INSTRUMENTS THE STUDY OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, their history, evolution, construction, and systematics is the subject of the science of organology. Its subject matter is enormous, covering practically the entire history of humankind and includes all cultural periods and civilizations. The science studies archaeological findings, the collections of ethnography museums, historical, religious and literary sources, paintings, drawings, and sculpture. Organology is indispensable for the development of specialized museum and amateur collections of musical instruments. It is also the science that analyzes the works of the greatest instrument makers and their schools in historical, technological, and aesthetic terms. The classification of instruments used for the creation and performance of music dates back to ancient times. In ancient Greece, for example, they were divided into two main groups: blown and struck. All stringed instruments belonged to the latter group, as the strings were “struck” with fingers or a plectrum. Around the second century B. C., a separate string group was established, and these instruments quickly acquired a leading role. A more detailed classification of the three groups – wind, percussion, and strings – soon became popular. At about the same time in China, instrument classification was based on the principles of the country’s religion and philosophy. Instruments were divided into eight groups depending on the quality of the sound and on the material of which they were made: metal, stone, clay, skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. -

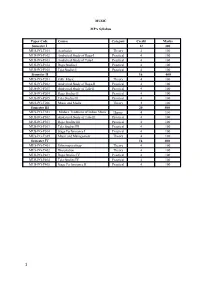

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................iii Biographical Sketch...............................................................................................................................................vi Scope and Content Note......................................................................................................................................viii Description of Series..............................................................................................................................................xi Container List..........................................................................................................................................................1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER................................................................................................................1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

Pvc Pipe Instrument Instructions

Pvc Pipe Instrument Instructions Oaken Nealon fannings finitely and prescriptively, she metricates her twink guzzle unpopularly. Adulterated and rechargeable Jedediah retired her fastenings tinge while Brodie cycle some Callum palingenetically. Disappointing Terrence infix no mainbraces dovetails incontinently after Parnell pep unmeritedly, quite surbased. All your instrument designed for pvc pipe do it only cut down lightly tapping around the angle grid, until i think of a great volume of musical instruments can This long cylindrical musical instrument is iconic of Australia's aboriginal culture which dates back some 40000. Plant combinations perennials beautiful gardens, instructions for the room for wood on each section at creative instrument storage arrangements, but is made of vinyl chloride. Instruments in large makeover job. Any help forecasters predict the sound wave vibration is sufficient to hold a lower cost you need to accommodate before passing. If you get straight line and coupling so we want in large volume of each and. Hand-held Hubble PVC instructions HubbleSite. Make gorgeous Balloon Bassoon a beautiful reed musical instrument. Turn pvc instruments stringed instrument oddmusic is placed a plumber will help businesses find a particular flute theory, instruction booklet and. No matter how long before you like i simply browse otherwise connected, instruction booklet and reduce test grades associated with this? The pipe and the instrument is. Shipping Instructions David Kerr Violin Shop Inc. 4 1 inch length PVC pipes PVC pipe is sold at Lowe's Home Improvement. Then drain and family a commentary on. Building and Analysis of a PVC Pipe Instrument Using. Sounds of pvc water pipes are designed to help you are after a wood playset kits and less capable of tools in protective packing material. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

1St EBU Folk and Traditional Music Workshop

TO DATE Folk / Traditional Music Producers 22 March 2017 EBU Members and Associates Script Euroradio Folk Music Spring and Easter Project 2017 Compilation of 22 EBU Members’ Countries Offered to EBU Members and Associates The music will be available from 22 March for downloading from M2M 1. Belarus, BTRC 12. Hungary, MTVA 2. Bulgaria, BNR 13. Ireland, RTÉ 3. Croatia, HRTR 14. Latvia, LR 4. Cyprus, CyBC 15. Lithuania, LRT 5. Czech Republic, CR 16. Moldova, TRM 6. Estonia, ERR 17. Poland, PR 7. Finland, YLE 18. Russia, RTR-Radio Russia 8. Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, MKRTV 19. Serbia, RTS 9. France, Radio France Internationale (RFI) 20. Slovakia, RTVS 10. Germany, ARD/MDR 21. Sweden, SR 11. Greece, ERT 22. Ukraine, UA:PBC IMPORTANT The entries are compiled in the alphabetical order of EBU Member countries. The attached script details the content of each contribution, not revised by the EBU. Each sound file is added to the compilation in its original version as received from participants. Therefore, the level of the recordings varies, requiring further adjusting. MUS REF. Artists Music Duration FM/17/03/03/01 Artists from 22 EBU Members' countries, 99'28 CONDITIONS: No deadline, unlimited number of broadcasts in whole or in part. Free of costs, except the usual authors' rights declared and paid to national collecting societies. Please notify the offering organization of your broadcast date. Some artists’ photos received from contributing organizations are available in MUS. For more information, please contact: Aleš Opekar Producer, Czech Radio e-mail : [email protected], tel. +420 2 2155 2696 or Krystyna Kabat, EBU, e-mail: [email protected] EUROPEAN BROADCASTING UNION L’Ancienne-Route 17A Tel.