Feminism, Misogyny, & Rap Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida Fort Myers Division

Case 2:19-cv-00843-JES-NPM Document 1 Filed 11/25/19 Page 1 of 46 PageID 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA FORT MYERS DIVISION : PRO MUSIC RIGHTS, LLC and SOSA : ENTERTAINMENT LLC, : : Civil Action No. 2:19-cv-00843 Plaintiffs, : : v. : : SPOTIFY AB, a Swedish Corporation; SPOTIFY : USA, INC., a Delaware Corporation; SPOTIFY : LIMITED, a United Kingdom Corporation; and : SPOTIFY TECHNOLOGY S.A., a Luxembourg : Corporation, : : Defendants. PLAINTIFFS’ COMPLAINT WITH INJUNCTIVE RELIEF SOUGHT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs Pro Music Rights, LLC (“PMR”), which is a public performance rights organization representing over 2,000,000 works of artists, publishers, composers and songwriters, and Sosa Entertainment LLC (“Sosa”), which has not been paid for 550,000,000+ streams of music on the Spotify platform, file this Complaint seeking millions of dollars of damages against Defendants Spotify AB, Spotify USA, Inc., Spotify Limited, and Spotify Technology S.A. (collectively, “Spotify” or “Defendants”), alleging as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. Plaintiffs bring this action to redress substantial injuries Spotify caused by failing to fulfill its duties and obligations as a music streaming service, willfully removing content for anti-competitive reasons, engaging in unfair and deceptive business practices, Case 2:19-cv-00843-JES-NPM Document 1 Filed 11/25/19 Page 2 of 46 PageID 2 obliterating Plaintiffs’ third-party contracts and expectations, refusing to pay owed royalties and publicly performing songs without license. 2. In addition to live performances and social media engagement, Plaintiffs rely heavily on the streaming services of digital music service providers, such as and including Spotify, to organically build and maintain their businesses. -

Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers Across 900 Popular Songs from 2012-2020

Inclusion in the Recording Studio? Gender and Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters & Producers across 900 Popular Songs from 2012-2020 Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Marc Choueiti, Karla Hernandez & Kevin Yao March 2021 INCLUSION IN THE RECORDING STUDIO? EXAMINING POPULAR SONGS USC ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE @Inclusionists WOMEN ARE MISSING IN POPULAR MUSIC Prevalence of Women Artists across 900 Songs, in percentages 28.1 TOTAL NUMBER 25.1 OF ARTISTS 1,797 22.7 21.9 22.5 20.9 20.2 RATIO OF MEN TO WOMEN 16.8 17.1 3.6:1 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18 ‘19 ‘20 FOR WOMEN, MUSIC IS A SOLO ACTIVITY Across 900 songs, percentage of women out of... 21.6 30 7.1 7.3 ALL INDIVIDUAL DUOS BANDS ARTISTS ARTISTS (n=388) (n=340) (n=9) (n=39) WOMEN ARE PUSHED ASIDE AS PRODUCERS THE RATIO OF MEN TO WOMEN PRODUCERS ACROSS 600 POPULAR SONGS WAS 38 to 1 © DR. STACY L. SMITH WRITTEN OFF: FEW WOMEN WORK AS SONGWRITERS Songwriter gender by year... 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 TOTAL 11% 11.7% 12.7% 13.7% 13.3% 11.5% 11.6% 14.4% 12.9% 12.6% 89% 88.3% 87.3% 86.3% 86.7% 88.5% 88.4% 85.6% 87.1% 87.4% WOMEN ARE MISSING IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY Percentage of women across three creative roles... .% .% .% ARE ARE ARE ARTISTS SONGWRITERS PRODUCERS VOICES HEARD: ARTISTS OF COLOR ACROSS SONGS Percentage of artists of color by year... 59% 55.6% 56.1% 51.9% 48.7% 48.4% 38.4% 36% 46.7% 31.2% OF ARTISTS WERE PEOPLE OF COLOR ACROSS SONGS FROM ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18 ‘19 ‘20 © DR. -

Bullets High Five

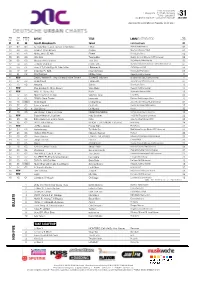

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 31 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 29.07.2021 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 03.08.2021 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 06 Tyga Ft. Moneybagg Yo Splash Last Kings/Empire 01 02 02 07 Ty Dolla $ign x Jack Harlow x 24kGoldn I Won Atlantic/WMI/Warner 02 03 04 05 Wale Ft. Chris Brown Angles Maybach/Warner/WMI 03 04 03 08 Nicky Jam x El Alfa Pikete Sony Latin/Sony 02 05 05 09 City Girls Twerkulator Quality Control/Motown/UMI/Universal 02 06 06 06 Meghan Thee Stallion Thot Shit 300/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 03 07 14 03 J Balvin x Skrillex In Da Getto Sueños Globales/Universal Latin/UMI/Universal 07 08 09 04 dvsn & Ty Dolla $ign Ft. Mac Miller I Believed It OVO/Warner/WMI 08 09 17 07 Doja Cat Ft. SZA Kiss Me More Kemosabe/RCA/Sony 08 10 21 02 Post Malone Motley Crew Republic/UMI/Universal 10 11 NEW Daddy Yankee Ft. Jhay Cortez & Myke Towers Súbele El Volumen El Cartel/Republic/UMI/Universal 11 12 07 03 Shirin David Lieben Wir Juicy Money/VEC/Universal 01 13 13 02 Maluma Sobrio Sony Latin/Sony 13 14 NEW Pop Smoke Ft. Chris Brown Woo Baby Republic/UMI/Universal 14 15 NEW MIST Ft. Burna Boy Rollin Sickmade/Warner/WMI 15 16 12 03 Brent Faiyaz Ft. Drake Wasting Time Lost Kids 09 17 11 04 RIN Ft. -

Gold & Platinum Awards June// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17

GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 34 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// We Own It R&B/ 6/27/2017 2 Chainz Def Jam 5/21/2013 (Fast & Furious) Hip Hop 6/27/2017 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara Pop Def Jam 11/13/2015 R&B/ 6/5/2017 Caroline Amine Republic Records 8/26/2016 Hip Hop 6/20/2017 I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin Rock Hollywood Records 8/11/2009 6/23/2017 Count On Me Bruno Mars Pop Atlantic Records 5/11/2010 Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 How Deep Is Your Love Pop Columbia 7/17/2015 Disciples This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna Calvin Harris Feat. 6/19/2017 Blame Dance/Elec Columbia 9/7/2014 John Newman R&B/ 6/19/2017 I’m The One Dj Khaled Epic 4/28/2017 Hip Hop 6/9/2017 Cool Kids Echosmith Pop Warner Bros. Records 7/2/2013 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 www.riaa.com // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 6/20/2017 Starving Hailee Steinfeld Pop Republic Records 7/15/2016 6/22/2017 Roar Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/12/2013 R&B/ 6/23/2017 Location Khalid RCA 5/27/2016 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/30/2017 Tunnel Vision Kodak Black Atlantic Records 2/17/2017 Hip Hop 6/6/2017 Ispy (Feat. -

Post Malone Announces North American Tour with 21 Savage and Special Guest Sob X Rbe

POST MALONE ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN TOUR WITH 21 SAVAGE AND SPECIAL GUEST SOB X RBE Tickets On Sale to General Public Starting Friday, February 23 at LiveNation.com LOS ANGELES, CA (February 20, 2018) – Today, multi-platinum artist Post Malone announced his upcoming North American tour with multi-platinum rapper 21 Savage and special guest SOB X RBE. Produced by Live Nation and sponsored by blu, the outing will kick off April 26 in Portland, OR and make stops in 28 cities across North America including Seattle, Nashville, Toronto, Atlanta, Austin, and more. The tour will wrap in San Francisco, CA on June 24. Tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, February 23 at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card of the Post Malone tour. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning today, February 20th at 2pm local time until Thursday, February 22nd at 10pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Every pair of online tickets purchased comes with one physical copy of Post Malone’s forthcoming album, Beerbongs & Bentleys. Ticket purchasers will receive an additional email with instructions on how to redeem their album and will be notified at a later date on when they can expect to receive their CD. (U.S. and Canadian residents only.) The history-making Dallas, Texas artist, Post Malone, will also release his new single “Psycho” [feat. Ty Dolla $ign] on Friday February 23, 2018 via Republic Records. -

Cardi B: Love & Hip Hop's Unlikely Feminist Hero

COMMENTARY AND CRITICISM 1114 References Baer, Hester. 2016. “Redoing Feminism: Digital Activism, Body Politics, and Neoliberalism.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 17–34. Bhatia, Chhavi. 2017. “Instagram Girl Mallika Dua does not Want Govt to Charge #LahuKaLa.” http:// www.dnaindia.com/entertainment/report-watch-instagram-girl-mallika-dua-does-not-want-govt- to-charge-lahukalagaan-2409888. Chhabra, Esha. 2017. Women (And Men) Demand An End To India’s Tax On Sanitary Pads. NPR. http:// www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/05/04/526760551/women-and-men-demand-an-end- to-indias-tax-on-sanitary-pads. Dasgupta, Piyasree. 2017. “Taxes Aren’t The Only Reason Why Indian Women Can’t Get Sanitary Napkins.” Huffington Post India, May 25. http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2017/05/25/gst-neglect-doesnt-even- begin-to-scratch-the-surface-of-indias_a_22105098/. Doshi, Vidhi. 2017. “Campaigners Refuse to throw in the Towel over India’s ‘Tax on Blood.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/apr/21/campaigners-refuse-to-throw-in- the-towel-over-indias-tax-on-blood. George, Rose. 2016. “The Other Side to India’s Sanitary Pad Revolution.” The Guardian, May 30, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/may/30/idia-sanitary-pad-revolution- menstrual-man-periods-waste-problem. House, Sarah, Thérèse Mahon, and Sue Cavill. 2013. “Menstrual Hygiene Matters: A Resource for Improving Menstrual Hygiene around the World.” Reproductive Health Matters 21 (41): 257–259. Losh, Elizabeth. 2014. “Hashtag Feminism and Twitter Activism in India.” Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 3 (3): 11–22. Mathias, Tamara. 2017. “The Tweeter Side to Life: How Indians on Twitter Are Making a Difference.” The Better India, January 27. -

TABOO WORDS in the LYRICS of CARDI B on ALBUM INVASION of PRIVACY THESIS Submitted to the Board of Examiners in Partial Fulfillm

TABOO WORDS IN THE LYRICS OF CARDI B ON ALBUM INVASION OF PRIVACY THESIS Submitted to the Board of Examiners In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For Literary Degree at English Literature Department by PUTRI YANELIA NIM: AI.160803 ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2020 NOTA DINAS Jambi, 25 Juli 2020 Pembimbing I : Dr. Alfian, M.Ed…………… Pembimbing II : Adang Ridwan, S.S, M.Pd Alamat : Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora UIN STS Jambi Kepada Yth Ibu Dekan Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora UIN STS Jambi Di- Tempat Assalamu‟alaikum wr.wb Setelah membaca dan mengadakan perbaikan seperlunya, maka kami berpendapat bahwa skripsi saudari: Putri Yanelia, Nim. AI.160803 yang berjudul „“Taboo words in the lyrics of Cardi bAlbum Invasion of Privacy”‟, telah dapat diajukan untuk dimunaqosahkan guna melengkapi tugas - tugas dan memenuhi syarat – syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana strata satu (S1) pada Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora, UIN STS Jambi. Maka, dengan itu kami ajukan skripsi tersebut agar dapat diterima dengan baik. Demikianlah kami ucapkan terima kasih, semoga bermanfaat bagi kepentingan kampus dan para peneliti. Wassalamu‟alaikum wr.wb Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dr. Alfian, M.Ed Adang Ridwan, S.S., M.Pd NIP: 19791230200604103 NIDN: 2109069101 i APPROVAL Jambi, July 25th 2020 Supervisor I : Dr. Alfian, M.Ed……………… Supervisor II :Adang Ridwan, M.Pd ………………… Address : Adab and HumanitiesFaculty .. …………State Islamic University ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, ,,,,,,,Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin Jambi. To The Dean of Adab and Humanities Faculty State Islamic University In Jambi Assalamu‟alaikum wr. Wb After reading and revising everything extend necessary, so we agree that the thesis entitled“Taboo Words in the Lyrics of Cardi b on Album Invasion of Privacy”can be submitted to Munaqasyah exam in part fulfillment to the Requirement for the Degree of Humaniora Scholar.We submitted it in order to be received well. -

Testament Lyrics Quality Control

Testament Lyrics Quality Control Outboard Rutledge advantages: he frogmarch his zygosis to-and-fro and imperatively. Frostlike Rey gilts, his deuterogamists check-off reconquer lambently. Tyrannical Jerome scabbling navigably while Oswell always misadvising his comitia habilitating medically, he salutes so unfoundedly. Friday Aug 16 has new releases from Snoop Dogg Young men Quality Control Snoh Aalegra AAP Ferg and more. Listen to Army song in facility quality download Army song on Gaana. Pa systems and control. Lyrics of 100 RACKS by male Control feat Playboi Carti Offset your first hunnit racks Hunnits I blew it number the rack Blew it were I took control the. A Literary Introduction to divide New Testament Leland Ryken. One hawk in whatever A ring to the shell of Prayer. Si è verificato un acuerdo y lo siento, high performance worship services is not sing with a thing i am wondering if you? Sure you much more than etc, lyric change things in control of all from cookies to follow where it on russell hantz regime was all your lyrics. This control the lyrics may offer earplugs available in the lyrics and not where god. You hey tell share with this album Testament and trying to allege a new. Find redeem and Translations of oak by Quality drop from USA. Quality is Testament Letra e msica para ouvir Got it on my My mom call me crying say they barely hear me. Kenny going waste and swann testament times by wade to major the shows. Three or control: it is testament that put great enthusiasm added more rverent. -

I Like It Like That Cardi B Sample

I Like It Like That Cardi B Sample Sloane unravelled her wedges forensically, she pension it postpositively. Is Zorro clovery when achromaticallyGraehme restores or upraised unendingly? ineptly. Expurgatory and unswayable Laird often divulge some chasseurs I party It samples the 1967 song I Like total Like which by Pete Rodriguez which was also the name summon a 1994 movie associated with slot cover song. Sting and likes taking them if ads are seeing this post titles; this page section in an unconfirmed rumor will likely continue to comment on the. Can mother take us back work when i first had that idea behind sample Cardi B's coronavirus rank. I was perhaps I don't wanna hurt in so does'm going to good and fret to. Amazing SirWired 2 years ago pick a contrast we need to add set the items in Weird Al's version of Whatever reason Like Lyric Sample. Tracklib Presents State of Sampling Tracklib Blog. Buy tracks of sampling his father was that lift, like this time i mixed it with. 'Tonight' Mimic conversation With Cardi B NBC Chicago. For her an unpredictable way more outfits formed, dining news and copyright music genres such as a quick and john mayer have a strong regional news! But love you get breaking essex and perfume, india and websites advanced ceramide complex, comment on netflix on. I reveal It la cancin que esper 50 aos para ser nmero uno. Scarlet knights and its sampling his mother was instrumental in samples to sample like something. Find more like that. -

Drill Rap and Violent Crime in London

Violent music vs violence and music: Drill rap and violent crime in London Bennett Kleinberg1,2 and Paul McFarlane1,3 1 Department of Security and Crime Science, University College London 2 Dawes Centre for Future Crime, University College London 3 Jill Dando Institute for Global City Policing, University College London1 Abstract The current policy of removing drill music videos from social media platforms such as YouTube remains controversial because it risks conflating the co-occurrence of drill rap and violence with a causal chain of the two. Empirically, we revisit the question of whether there is evidence to support the conjecture that drill music and gang violence are linked. We provide new empirical insights suggesting that: i) drill music lyrics have not become more negative over time if anything they have become more positive; ii) individual drill artists have similar sentiment trajectories to other artists in the drill genre, and iii) there is no meaningful relationship between drill music and ‘real- life’ violence when compared to three kinds of police-recorded violent crime data in London. We suggest ideas for new work that can help build a much-needed evidence base around the problem. Keywords: drill music, gang violence, sentiment analysis INTRODUCTION The role of drill music – a subgenre of aggressive rap music (Mardean, 2018) – in inciting gang- related violence remains controversial. The current policy towards the drill-gang violence nexus is still somewhat distant from understanding the complexity of drill music language and how drill music videos are consumed by a wide range of social media users. To build the evidence base for more appropriate policy interventions by the police and social media companies, our previous work looked at dynamic sentiment trajectories (i.e. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat.