Astronomical Calculation of the Dating the Historical Battles of Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis Based on Herodotus’ Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

SUPPLEMENTARY SECTION 12,800 Years Ago, Hellas and the World on Fire and Flood Volker Joerg Dietrich, Evangelos Lagios and Gregor Zographos

SUPPLEMENTARY SECTION 12,800 years ago, Hellas and the World on Fire and Flood Volker Joerg Dietrich, Evangelos Lagios and Gregor Zographos Supplements 1 The Geotectonic Framework of the Pagasitic Gulf 1.1 Alpine Tectonic Structures 2 Surficial Cataclastic and Brittle Deformation 2.1 Macroscopic Scale (Breccia Outcrops) 2.1.1 Striation and Shatter Cones 2.2 Microscopic Scale 2.2.1 Planer Deformation in Quartz 2.2.2 Planer Deformation in Calcite 2.3 Metamorphic and Post-Alpine Hydrothermal Activity (Veining) 3 Geophysical Investigations of Pagasitic Gulf and Surrounding Areas Gravity Measurements and Modelling 1 The Geotectonic Framework of the Pagasitic Gulf The Geotectonic frame of the Pagasitic Gulf is best exposed in the sickle shaped Pelion Peninsula (Figs. 1&2) and applies to all mountain ranges and coastal areas around the gulf, which are part of the “Internal Alpine-Dinaride-Hellenide Orogen”. Fig. 1 Google Earth image of the Pagasitic Gulf – Mt. Pelio area; bathymetry according to Perissoratis et al. 1991; Korres et al. 2011; Petihakis et al. 2012. White Circle on the western side of the image: The Zerelia Twin-Lakes: Two Possible Meteorite Craters (Dietrich et al. 2017). 0 1.1 Alpine Tectonic Structures The internal structure of Pindos and Pelagonian thrust sheet units is extremely complex and has not yet been worked out in detail. In addition, towards north overthrust units of the Axios-Vardar realm cover the Pelagonian thrust sheets (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 Synthetic cross section through the Olympos region between the “External Hellenides” and the “Axios/Vardar tectonic nappe system” after Schenker et al. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

An Analysis of Foreign Policy Motivation in the Peloponnesian War

Review of International Studies (2001), 27, 69–90 Copyright © British International Studies Association ‘Chiefly for fear, next for honour, and lastly for profit’: an analysis of foreign policy motivation in the Peloponnesian War WILLIAM O. CHITTICK AND ANNETTE FREYBERG-INAN Abstract. This article applies a three-dimensional framework for the analysis of the role of motivation in foreign policy decision-making to the foreign policy decisions of individuals and cities in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. First, the authors briefly intro- duce their framework for analysis. Using the speeches in Thucydides to explicate the motives and goals of individuals and cities, the authors then trace the relationships between the motivational dispositions of foreign policy actors and their foreign policy behaviour. In so doing, they demonstrate both the relevance of a concern with individual motivation for foreign policy analysis and the usefulness of their analytical framework for studying the impact of the relevant motives. The authors also show how ideological statements can be ana- lysed to determine the relative salience of individual motives and collective goals, suggesting a relationship between ideological reasoning and motivational imbalance which can adversely affect the policymaking process. In conclusion, they briefly assess the theoretical and norma- tive as well as practical policy implications of their observations. Introduction The study of foreign policy entails the analysis of human reactions to the threats, challenges, and opportunities presented by the international environment. However, foreign policy decision-makers do not react directly to situations or events. Instead, they react according to the ways in which they perceive and interpret those situations and events. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

The Tyrannies in the Greek Cities of Sicily: 505-466 Bc

THE TYRANNIES IN THE GREEK CITIES OF SICILY: 505-466 BC MICHAEL JOHN GRIFFIN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Classics September 2005 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank the Thomas and Elizabeth Williams Scholarship Fund (Loughor Schools District) for their financial assistance over the course of my studies. Their support has been crucial to my being able to complete this degree course. As for academic support, grateful thanks must go above all to my supervisor at the School of Classics, Dr. Roger Brock, whose vast knowledge has made a massive contribution not only to this thesis, but also towards my own development as an academic. I would also like to thank all other staff, both academic and clerical, during my time in the School of Classics for their help and support. Other individuals I would like to thank are Dr. Liam Dalton, Mr. Adrian Furse and Dr. Eleanor OKell, for all their input and assistance with my thesis throughout my four years in Leeds. Thanks also go to all the other various friends and acquaintances, both in Leeds and elsewhere, in particular the many postgraduate students who have given their support on a personal level as well as academically. -

1 UNIT 3 the SOPHISTS Contents 3.0. Objectives 3.1. Introduction 3.2

UNIT 3 THE SOPHISTS Contents 3.0. Objectives 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Protagoras 3.3. Prodicus 3.4. Hippias 3.5. Gorgias 3.6. The Lesser Sophists 3.7. Let Us Sum Up 3.8. Key Words 3.9. Further Readings and References 3.10. Answers to Check Your Progress 3.0. OBJECTIVES In this Unit we explain in detail the Sophist movement and their philosophical insights that abandoned all abstract, metaphysical enquiries concerning the nature of the cosmos and focused on the practical issues of life. By the end of this Unit you should know: Their foul or fair argumentation Epistemological and ethical skepticism and relativism of the Sophists The differentiation between the early philosophers and Sophists The basic philosophical positions of Protagoras, Prodicus, Hippias and Gorgias 3.1. INTRODUCTION Sophist movement flourished in 5th century B.C., shortly before the emergence of the Socratic period. Xenophon, a historian of 4th century B.C., describes the Sophists as wandering teachers 1 who offered wisdom for sale in return for money. The Sophists were, then, professional teachers, who travelled about, from city to city, instructing people, especially the youth. They were paid large sums of money for their job. Until then teaching was considered something sacred and was not undertaken on a commercial basis. The Sophists claimed to be teachers of wisdom and virtue. These terms, however, did not have their original meaning in sophism. What they meant by these terms was nothing but a proficiency or skillfulness in practical affairs of daily life. This, they claimed, would lead people to success in life, which, according to them, consisted in the acquisition and enjoyment of material wealth as well as positions of power and influence in society. -

Περίληψη : Darius I Was King of the Persian Empire from 522/521 to 486/485 BC

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Νούτσου Μαρίνα Μετάφραση : Βελέντζας Γεώργιος (18/7/2005) Για παραπομπή : Νούτσου Μαρίνα , "Darius I", 2005, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=6771> Περίληψη : Darius I was king of the Persian Empire from 522/521 to 486/485 BC. He expanded the boundaries of the Persian Empire, reorganized the administration into satrapies and created a detailed financial system for the administration of the country's resources. He squashed the Ionian Revolt and campaigned against Scythia and Greece. He supported the development of the arts and architecture. Άλλα Ονόματα Darajava(h)us, Darjawes, Dareiaios, Dareian, King of the Peoples, King of the Kings, Great King, Great Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 550-549 BC (approximately) Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 486/485 BC Κύρια Ιδιότητα Official at the royal court, King of the Persian Empire 1. Birth-Family Darius I was the King of the Persian Empire from 522/521 until 486/485 BC. His name means ‘he who has the power’or ‘he who maintains the good’.1 Ancient sources do not mention the year he was born. However, this is estimated circa 550-549 BC, according to information from Herodotus2, who says that Darius I was approximately 20 years old when King Cyrus II was killed, which happened between 530 and 529 BC. There is more information about his origins.3 He was the eldest son of Hystaspes, descendant of Ariaramnes of the Persian dynasty of the Achaemenids. Darius’father was an officer by Cyrus II, whom he followed in the campaign against the Massagetai. -

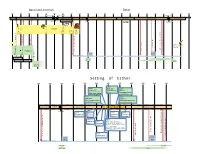

Setting of Esther

Daniel and Jeremiah Esther 610 600 590 580 570 560 550 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 420 410 400 Amel-marduk 561-560 Labashi-marduk 556 Xerxes II 425-424 Cambyses Nabopolassar Nebuchadnezzar 605-562 Nabonidus 556-536 Cyrus 539-530 Darius I 521-486 Xerxes I 486-465 Artaxerxes I 465-424 Darius II 423-404 625-605 529-522 Nergal-shal-usur 559-557 Belshazzar 553-539 Smerdis 522 ESTHER Sogdianus 424-423 DANIEL 12 - 8 - Dan 3 Dan Dan 2 Dan 4 Dan 7 Dan 6, 9 5, Dan 10 Dan The The statue dream, 604 Fiery furnace, c603 The tree dream, c571 Vision of four beasts, 553 Vision of ram &goat, 551 Fall of Babylon, 539 Lion’s den Reading of Jeremiah, 539 Vision of the end, 536 , 538 , Deportation, Deportation, 605 st 1 Deportation, 597 Deportation, Deportation, 587 Deportation, Sheshbazzar nd rd Letters sent from Jews at 2 3 Elephantine to Yohanan, high priest in Jerusalem, 410 and 407 Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes, Artaxerxes, 433 Nehemiah toreturned visit of Nehemiah, Nehemiah, 432 visit of visit of Nehemiah, 445 visitof Nehemiah, return, return, led by st nd Return of Ezra, 458 of Return Ezra, 1 2 st JEREMIAH 1 Walls of 29 25 Temple Jerusalem rebuilt Jer Jer Message Message to exiles, 597 Prophecy Prophecy of captivity, 605 rebuilt, Temple foundation laid 520-516 443 Jehoiakim 609-598 HAGGAI NEHEMIAH Jehoiachin 608-597 Zedekiah 597-587 flight585 to Forced Egypt, ZECHARIAH EZRA MALACHI 44 Jer Prophecy Prophecy against refugees in Egypt Setting of Esther 540 530 520 510 500 490 480 470 460 450 440 430 478 BC 482 BC Esther 2:16 474 -

Persian Heri Tage

Persian Heri tage Persian Heritage Vol. 19, No. 75 Fall 2014 www.persian-heritage.com Persian Heritage, Inc. FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK 6 110 Passaic Avenue LETTERS TO EDITOR 8 Passaic, NJ 07055 E-mail: [email protected] Remember Me (Azar Aryanpour) 8 Telephone: (973) 471-4283 NEWS 9 Fax: 973 471 8534 Ten Most Influential Minds 9 EDITOR The Committee 11 SHAHROKH AHKAMI My Mother, Our Mother (Zia Ghavami) 11 EDITORIAL BOARD COMMENTARY Dr. Mehdi Abusaidi, Shirin Ahkami Raiszadeh, Dr. Mahvash Alavi Naini, Iran and Germany a 100-Year Old Love Affair 13 Mohammad Bagher Alavi, Dr. Talat Bassari, Mohammad H. Hakami, (Amir Taheri) Ardeshir Lotfalian, K. B. Navi, Dr. Kamshad Raiszadeh, Farhang A. I Think of Thee (Elizabeth Barrett Browing) 14 Sadeghpour, Mohammad K. Sadigh, Dr. David Yeagley. By Rooting for the Iranian World Cup Soccer, ... 15 (Shirin Najafi) MANAGING EDITOR HALLEH NIA THE ARTS & CULTURE ADVERTISING REVIEWS 17 HALLEH NIA Persian Dance (Nima Kiann) 18 * The contents of the articles and ad ver tisements in this journal, with the ex ception A Guide to Guidebooks on Iran (Rasoul Sorkhabi) 21 of the edi torial, are the sole works of each in di vidual writers and contributors. This maga Persian, From Thinking to Speaking (Amir-Jahed) 22 zine does not have any confirmed knowledge as to the truth and ve racity of these articles. Interview with Iraj Pezeshkzad 23 all contributors agree to hold harmless and indemnify Persian Heri tage (Mirass-e Iran), (Shahrokh Ahkami) Persian Heritage Inc., its editors, staff, board of directors, and all those in di viduals di rectly A Perpetual Paradigm... -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T

Pindar Fr. 75 SM and the Politics of Athenian Space Richard T. Neer and Leslie Kurke Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow. Anne Carson, “The Life of Towns” T IS WELL KNOWN that Pindar’s poems were occasional— composed on commission for specific performance settings. IBut they were also, we contend, situational: mutually im- plicated with particular landscapes, buildings, and material artifacts. Pindar makes constant reference to precious objects and products of craft, both real and metaphorical; he differs, in this regard, from his contemporary Bacchylides. For this reason, Pindar provides a rich phenomenology of viewing, an insider’s perspective on the embodied experience of moving through a built environment amidst statues, buildings, and other monu- ments. Analysis of the poetic text in tandem with the material record makes it possible to reconstruct phenomenologies of sculpture, architecture, and landscape. Our example in this essay is Pindar’s fragment 75 SM and its immediate context: the cityscape of early Classical Athens. Our hope is that putting these two domains of evidence together will shed new light on both—the poem will help us solve problems in the archaeo- logical record, and conversely, the archaeological record will help us solve problems in the poem. Ultimately, our argument will be less about political history, and more about the ordering of bodies in space, as this is mediated or constructed by Pindar’s poetic sophia. This is to attend to the way Pindar works in three dimensions, as it were, to produce meaningful relations amongst entities in the world.1 1 Interest in Pindar and his material context has burgeoned in recent ————— Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 54 (2014) 527–579 2014 Richard T.