Download the Issue As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twelve Greatest Air Battles of the Tuskegee Airmen

THE TWELVE GREATEST AIR BATTLES OF THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN Daniel L. Haulman, PhD Chief, Organizational Histories Branch Air Force Historical Research Agency 25 January 2010 edition Introduction The 332d Fighter Group was the only African-American group in the Army Air Forces in World War II to enter combat overseas. It eventually consisted of four fighter squadrons, the 99th, 100th, 301st, and 302d. Before the 332d Fighter Group deployed, the 99th Fighter Squadron, had already taken part in combat for many months. The primary mission of the 99th Fighter Squadron before June 1944 was to launch air raids on ground targets or to defend Allied forces on the ground from enemy air attacks, but it also escorted medium bombers on certain missions in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. When the 332d Fighter Group first deployed to Italy in early 1944, it also flew patrol, close air support, and interdiction tactical missions for the Twelfth Air Force. Between early June 1944 and late April 1945, the 332d Fighter Group, which the 99th Fighter Squadron joined, flew a total of 311 missions with the Fifteenth Air Force. The primary function of the group then, along with six other fighter groups of the Fifteenth Air Force, was to escort heavy bombers, including B-17s and B-24s, on strategic raids against enemy targets in Germany, Austria, and parts of Nazi-occupied central, southern, and Eastern Europe. This paper focuses on the twelve greatest air battles of the Tuskegee Airmen. They include the eleven missions in which the 332d Fighter Group, or the 99th Fighter Squadron before deployment of the group, shot down at least four enemy aircraft. -

The War Years

1941 - 1945 George Northsea: The War Years by Steven Northsea April 28, 2015 George Northsea - The War Years 1941-42 George is listed in the 1941 East High Yearbook as Class of 1941 and his picture and the "senior" comments about him are below: We do know that he was living with his parents at 1223 15th Ave in Rockford, Illinois in 1941. The Rockford, Illinois city directory for 1941 lists him there and his occupation as a laborer. The Rockford City Directory of 1942 lists George at the same address and his occupation is now "Electrician." George says in a journal written in 1990, "I completed high school in January of 1942 (actually 1941), but graduation ceremony wasn't until June. In the meantime I went to Los Angeles, California. I tried a couple of times getting a job as I was only 17 years old. I finally went to work for Van De Camp restaurant and drive-in as a bus boy. 6 days a week, $20.00 a week and two meals a day. The waitresses pitched in each week from their tips for the bus boys. That was another 3 or 4 dollars a week. I was fortunate to find a garage apartment a few blocks from work - $3 a week. I spent about $1.00 on laundry and $2.00 on cigarettes. I saved money." (italics mine) "The first part of May, I quit my job to go back to Rockford (Illinois) for graduation. I hitch hiked 2000 miles in 4 days. I arrived at my family's house at 4:00 AM one morning. -

Australian War Memorial Poppy Display

INFORMATION SUPERIORITY DELIVERING NEXT GENERATION INTEGRATED SYSTEMS TO AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FOR 25 YEARS Ocean Software is a 100% Australian owned Data Systems Integrator, with expertise in complex operations, aviation systems, and health knowledge management. We support 13 Militaries across 14 Countries through the development and delivery of high quality COTS software products. SOFTWARE REPORTING & E-HEALTH AVIATION IT SERVICES & ENGINEERING DATA ANALYSIS OPERATIONS PROJECT MNGMT LMS, LCMS & COMMAND & SYSTEM PROCESS CURRENCY & TRAINING SERVICES CONTROL INTEGRATION OPTIMISATION QUALIFICATIONS www.ocean.software RAAF Wings - MILCIS Edition Full Page Ad V1.indd 1 4/10/2017 1:48:55 PM INSIDE Master Volume 70 No 4 AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION PUBLICATION Editor Mark Eaton [email protected] PO Box 1269 Bondi Junction NSW 1355 17 President Carl Schiller OAM CSM Vice Presidents Governance Bob Bunney Advocacy & Entitlements Richard Kelloway OBE Communications & Media Lance Halvorson MBE 40 25 Secretary Peter Colliver [email protected] Treasurer Bob Robertson Publisher FEATURES REGULARS Flight Publishing Pty Ltd [email protected] DIVISION CONTACTS ACT [email protected] INFORMATION SUPERIORITY 0428 622 105 Formation of the Air 4 National Council 8 NSW [email protected] Academy DELIVERING NEXT GENERATION INTEGRATED 02 9393 3485 35 Air Force Today QLD [email protected] 12 Officer Aviation 0417 452 643 40 Defence Talk SYSTEMS TO AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FOR 25 YEARS SA [email protected] 08 8227 0980 14 Above the Same Sky Ocean Software is a 100% Australian owned Data Systems Integrator, with expertise in complex TAS [email protected] 45 Air Force Cadets operations, aviation systems, and health knowledge management. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

Copyright © 2020 Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum 1

Individual Object History Hawker Hurricane IIc LF738/5405M Museum Object Number 1995/1004/A Built by Hawkers at Langley to contract No.L62305/39/C parts 13/19, part of the final batch of 1,357 Hurricanes built at Langley and Kingston, from serial number batch LF737 - LF774. Fitted with Merlin XX engine. 19 Mar 44 To No.22 MU RAF Silloth, Cumbria, for storage. 10 Apr 44 To No.1682 BDTF (Bomber Defence Training Flight) RAF Enstone, Oxon carrying the codes UH - This unit was tasked with Fighter affiliation - `bouncing' bombers from local OTU's to train their gunners. LF738 was one of a number of Hurricanes delivered April 44 to replace the units' Curtiss Tomahawk aircraft. 21 Aug 44 No.1682 BDTF Disbanded. 23 Aug 44 To No.22 OTU, RAF Wellesbourne Mountford, Warwickshire. This was a night bomber-training unit and LF738 may have been used for further fighter affiliation work, carrying the unit codes LT - By December 1944 the unit had on strength 6 Hurricanes, including LF738, 54 Wellingtons and two Miles Masters. 01 Jul 45 Final course at No.22 OTU completed and all flying ceased. Unit disbanded 24 Jul 45. 16 Jul 45 Allotted instructional serial 5405M as one of five Hurricanes sent from Wellesbourne to No.12 School of Technical Training at RAF Melksham, Wilts. 6 Sep 54 Allotted to RAF Biggin Hill, Kent. 19 Sep 54 Dedicated by the Bishop of Rochester, together with Spitfire LF16 SL674 at a drumhead Sunday service at Biggin Hill as a permanent memorial and gate guard to St Georges' Chapel of Remembrance - the BoB Chapel at the station, and moved into place in front of the newly completed chapel the following year. -

Doolittle and Eaker Said He Was the Greatest Air Commander of All Time

Doolittle and Eaker said he was the greatest air commander of all time. LeMayBy Walter J. Boyne here has never been anyone like T Gen. Curtis E. LeMay. Within the Air Force, he was extraordinarily successful at every level of com- mand, from squadron to the entire service. He was a brilliant pilot, preeminent navigator, and excel- lent bombardier, as well as a daring combat leader who always flew the toughest missions. A master of tactics and strategy, LeMay not only played key World War II roles in both Europe and the Pacific but also pushed Strategic Air Command to the pinnacle of great- ness and served as the architect of victory in the Cold War. He was the greatest air commander of all time, determined to win as quickly as possible with the minimum number of casualties. At the beginning of World War II, by dint of hard work and train- ing, he was able to mold troops and equipment into successful fighting units when there were inadequate resources with which to work. Under his leadership—and with support produced by his masterful relations with Congress—he gained such enor- During World War II, Gen. Curtis E. LeMay displayed masterful tactics and strategy that helped the US mous resources for Strategic Air prevail first in Europe and then in the Pacific. Even Command that American opponents Soviet officers and officials acknowledged LeMay’s were deterred. brilliant leadership and awarded him a military deco- “Tough” is always the word that ration (among items at right). springs to mind in any consideration of LeMay. -

JCLD Fall 2020

)$// 92/80(_,668( (GLWRULQ&KLHI 'U'RXJODV/LQGVD\/W&RO 5HW 86$) &(17(5)25&+$5$&7(5 /($'(56+,3'(9(/230(17 EDITORIAL STAFF: EDITORIAL BOARD: Center for Creative Leadership Dr. Douglas Lindsay, Lt Col (Ret), USAF Dr. David Altman, Editor in Chief Dr. Marvin Berkowitz, University of Missouri- St. Louis Dr. John Abbatiello, Col (Ret), USAF Book Review Editor Dr. Dana Born, Harvard University (Brig Gen, USAF, Retired) Dr. Stephen Randolph Dr. David Day, Claremont McKenna College Profiles in Leadership Editor Dr. Shannon French, Case Western Julie Imada Associate Editor & CCLD Strategic Dr. William Gardner, Texas Tech University Communications Chief Mr. Chad Hennings, Hennings Management Corp JCLD is published at the United States Air Mr. Max James, American Kiosk Management Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Articles in JCLD may be reproduced in whole Dr. Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University or in part without permission. A standard Dr. Robert Kelley, Carnegie Mellon University source credit line is required for each reprint or citation. Dr. Richard M. Lerner, Tufts University For information about the Journal of Character Ms. Cathy McClain, Association of Graduates and Leadership Development or the U.S. Air (Colonel, USAF, Retired) Force Academy’s Center for Character and Dr. Michael Mumford, University of Oklahoma Leadership Development or to be added to the Journal’s electronic subscription list, contact Dr. Gary Packard, University of Arizona (Brig Gen, us at: [email protected] USAF, Retired) Phone: 719-333-4904 Dr. George Reed, University of Colorado at The Journal of Character & Leadership Colorado Springs (Colonel, USA, Retired) Development The Center for Character & Leadership Dr. -

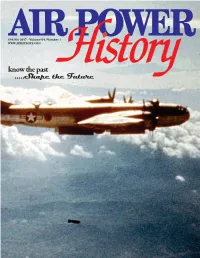

Spring 2017 Issue-All

SPRING 2017 - Volume 64, Number 1 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Winter 2009

SPINE AIR & SP A CE Winter 2009 Volume XXIII, No. 4 P OWER JOURN Directed Energy A Look to the Future Maj Gen David Scott, USAF Col David Robie, USAF A L , W Hybrid Warfare inter 2009 Something Old, Not Something New Hon. Robert Wilkie Preparing for Irregular Warfare The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be Col John D. Jogerst, USAF, Retired Achieving Balance Energy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency Col John B. Wissler, USAF US Nuclear Deterrence An Opportunity for President Obama to Lead by Example Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force 2009-4 Outside Cover.indd 1 10/27/09 8:54:50 AM SPINE Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck http://www.af.mil Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF, Retired Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Darlene H. Barnes, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the http://www.au.af.mil presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. -

Eib Information

EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BAN ¡998 1958 Φ+ilô EIB INFORMATION DEN EUROPÆISKE INVESTERINGSBANK BANQUE EUROPEENNE D'INVESTISSEMENT EUROPÄISCHE INVESTITIONSBANK BANCA EUROPEA PER GII INVESTIMENTI EUROPESE INVESTERINGSBANK ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΤΡΑΠΕΖΑ ΕΠΕΝΔΥΣΕΩΝ BANCO EUROPEU DE INVESTIMENTO 1 1998·Ν°96 EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK EUROOPAN INVESTOINTIPANKKI ISSN 02503891 BANCO EUROPEO DE INVERSIONES EUROPEISKA INVESTERINGSBANKEN 1997: European Investment Bank aunches ¡ob-support action plan and strengthens its commitment to EMU In 1997, the European Investment Bank intensified its support for economic and social cohesion in Europe in the run up to Economic and Monetary Union. The Bank launched a special action programme to encourage job-creating investment to underpin the European Union's growth and employment policies, and expanded its financing for investment in key areas sucri as regional development and Trans-European Networks. Total lending in the year increased by 13%, to ECU 26.2 billion (of which ECU 23 billion was in the Member States of the Union) and the Bank borrowed ECU 23 billion on the international capital markets, making it the world's largest non-sovereign borrower. "Our two top priorities during 1997 have been to step up our activities to help the European Union move successfully towards Economic and Monetary Union and the single currency and to prepare the way for the Union's enlargement. We responded rapidly and in a practical way to the Resolution on Growth and Employment of the June Amsterdam Summit by launching our Amsterdam Special Action Programme (ASAP). This is now well under way with substantial financing operations already con cluded in the areas of health and education and through a "special window" for venture capital, in the high-growth, technology oriented, small and medium-sized enterprise sector. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

Chasing Success

AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Chasing Success Air Force Efforts to Reduce Civilian Harm Sarah B. Sewall Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Sewall, Sarah B. Copy Editor Carolyn Burns Chasing success : Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm / Sarah B. Sewall. Cover Art, Book Design and Illustrations pages cm L. Susan Fair ISBN 978-1-58566-256-2 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Air power—United States—Government policy. Nedra O. Looney 2. United States. Air Force—Rules and practice. 3. Civilian war casualties—Prevention. 4. Civilian Print Preparation and Distribution Diane Clark war casualties—Government policy—United States. 5. Combatants and noncombatants (International law)—History. 6. War victims—Moral and ethical aspects. 7. Harm reduction—Government policy— United States. 8. United States—Military policy— Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. II. Title: Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm. UG633.S38 2015 358.4’03—dc23 2015026952 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Published by Air University Press in March 2016 Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes Design and Production Manager Cheryl King Air University Press 155 N. Twining St., Bldg. 693 Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 [email protected] http://aupress.au.af.mil/ http://afri.au.af.mil/ Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the organizations with which they are associated or the views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any AFRI other US government agency.