Integrating Resource Access 19May2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin

A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY LAKE VICTORIA BASIN COMMISSION A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin © Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) Lake Victoria Basin Commission P.O. Box 1510 Kisumu, Kenya African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS) P.O. Box 459178-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Printed and bound in Kenya by: Eyedentity Ltd. P.O. Box 20760-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya: ACTS Press, African Centre for Technology Studies, Lake Victoria Basin Commission, 2011 ISBN 9966-41153-4 This report cannot be reproduced in any form for commercial purposes. However, it can be reproduced and/or translated for educational use provided that the Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) is acknowledged as the original publisher and provided that a copy of the new version is received by Lake Victoria Basin Commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Copyright i ACRONYMS iii FOREWORD v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi 1. BACKGROUND 1 1.1. The Lake Victoria Basin and Its Aquatic Resources 1 1.2. The Lake Victoria Basin Commission 1 1.3. Justification for the Study 2 1.4. Previous efforts to develop Database on Lake Victoria 3 1.5. Global perspective of biodiversity 4 1.6. The Purpose, Objectives and Expected Outputs of the study 5 2. METHODOLOGY FOR ASSESSMENT OF BIODIVERSITY 5 2.1. Introduction 5 2.2. Data collection formats 7 2.3. Data Formats for Socio-Economic Values 10 2.5. Data Formats on Institutions and Experts 11 2.6. -

Illegal Fishing on Lake Victoria How Joint Operations Are Making an Impact December 2016

STOP ILLEGAL FISHING CASE STUDY SERIES 12 Illegal fishing on Lake Victoria How joint operations are making an impact December 2016 Background Many initiatives have been undertaken – especially in the Lake Victoria is an important source area of monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) – to of freshwater fish, contributing address the challenges of illegal fishing on Lake Victoria. significantly to the economies of For example, community-based Beach Management Units Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda and the 3 livelihoods and nutrition of three million (BMUs) have been established to legally represent each people. fishing community and undertake MCS activities; an MCS Nile perch, introduced in the 1950s, Regional Working Group (RWG-MCS) has been established became the most important species in to coordinate MCS activities; and the industrial fish the lake decimating the endemic fish processors exercise self-regulation in order to sustain their and, creating a lucrative commercial exports. However the problem continues, to an extent due fishery. Over-fishing and the use of destructive fishing gear has reduced to a lack of equipment and financing as well as technical the stock of larger, legal sized Nile capacity to implement MCS operations. perch1, resulting in the illegal trade of undersized fish. The Chinese market Faced with a continuing decline in the Nile perch stocks, for dried swim bladders has removed the LVFO Council of Ministers asked the SmartFish spawners from the stock, further Programme to work with all three member states to affecting its ability to recover. strengthen MCS of the lake fisheries. This took the form of The Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization capacity building in the first year, to develop professional (LVFO) was formed in 1994, but illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) MCS teams, followed by practical operations for the fishing continues to have a severe remaining three years. -

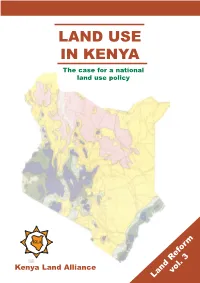

LAND USE in KENYA the Case for a National Land Use Policy

landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page i LAND USE IN KENYA The case for a national land use policy Kenya Land Alliance ol. 3 v Land Reform landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page ii II Credits Published by: Kenya Land Alliance Printing House Road PO Box 7150, Nakuru Tel: +254 37 41203 Email: [email protected] Text by: Consultants for Natural Resources Management PO Box 62702, Nairobi Tel: +254 2 723958; 0733-747677 Fax: +254 2 729607 Email: [email protected] Edited By: Ms. Dali Mwagore PO Box 30677, Nairobi Design and Layout: Creative Multimedia Communications Limited PO Box 56196, Nairobi Tel: +254 2 230048 ISBN 9966-896-92-2 Printed by: Printfast Kenya Limited PO Box Nairobi Tel: 557051 Land Use in Kenya • The case for a national land-use policy landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page iii Cover iii Alpine moorland (water catchments) Humid (intensive agriculture/forestry) Humid (intensive mixed farming) Semi-humid (mixed dryland farming) Semi-arid (pastoralism/wildlife) Arid (nomadic pastoralism) Land Use in Kenya • The case for a national land-use policy landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page iv iv Contents Contents Acknowledgement vi Preface vii Summary viii Acronyms ix Introduction: Land use in Kenya 2 Chapter One: Land resources in Kenya 1.1 Agricultural land potential 5 1.2 Forest resources 10 1.3 Savannahs and grasslands 15 1.4 Water resources 20 1.5 Fisheries 25 1.6 Wetlands 27 1.7 Wildlife resources 29 1.8 Mineral resources 31 1.9 Energy 33 Chapter Two: Land abuse in Kenya 2.1 Soil erosion 37 2.2 Pollution 42 2.3 The polluting agents 44 2.4 Urban -

Socio-Economic Impacts of Trawling in Lake Victoria 26

Socio-Economic Impacts of Trawling in Lake Victoria. Item Type Report Section Authors Abila, R. Publisher IUCN Eastern Africa Regional Office Download date 26/09/2021 09:44:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/7261 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF TRAWLING IN LAKE VICTORIA RICHARD O. ABILA Research Officer Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute P.O. Box 1881 Kisumu, Kenya Introduction Trawling is a unique technique of harvesting fish on Lake Victoria. It is a modern method requiring relatively high capital investment and is capable of using complex scientific gadgets in monitoring and hauling fish. The fish caught by an average trawler may be many times what a local fishing unit may produce. Therefore, a trawler will yield higher catch per unit of labour and time input in a fishing operation than the traditional fishing boats. There is an official ban in place on commercial trawling in all three East African countries. Despite this, illegal trawling has persisted, presumably with the tacit knowledge of the government officers responsible for enforcing the ban. It appears that the incentives and profits attained in trawling are so high that some trawler owners continue in the business even at the risk of being prosecuted. Alternatively it may be that trawler owners are very powerful and influential people in business or in the civil service. Evidence shows that among the initial owners of trawl boats in Kenya were top government officials, including a Cabinet Minister and an Assistant Director of Fisheries living in the lake region. The profit motives and the powerful forces in the trawler industry effectively ensured that "disused" and non-performing vessels previously owned by the government of Kenya for the delivery of social services, in patrolling the lake and transporting passengers and goods, were purchased by private businessmen and renovated into trawlers. -

TRAWLING in LAKE VICTORIA: Its History, Status and Effects

Socio-economics of the Lake Victoria Fisheries TRAWLING IN LAKE VICTORIA: Its History, Status and Effects James Siwo Mbuga and Albert Getabu Andrew Asila Modesta Medard Richard Abila Lake Victoria is the second biggest freshwater lake in the world. With its 69,000 km2, the lake has the same size as Ireland. The lake is shared between three countries; Tanzania (which possesses 49%), Uganda (45%) and Kenya (6%) of the lake. The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or the partner organisations in this project. Newspaper Cuttings: All newspaper cuttings (clips) included in this report are excerpts of Daily Nation articles appearing on various dates on the subject of trawling (except the cutting on page 30 which is from the East African Standard of 6th July, 1998). Design & Layout: IUCN EARO Communications Unit Table of Contents PREFACE .............................................................................................................................................. 3 SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................ 4 TRAWLING IN THE KENYAN PART OF LAKE VICTORIA.......................................................... 5 THE DEVELOPMENT AND PROSPECTS OF EXPERIMENTAL AND COMMERCIAL TRAWLING IN LAKE VICTORIA.................................................................................................... 14 TRAWLING ON THE NYANZA GULF IN -

FISHERIES MANAGEMENT on LAKE VICTORIA, TANZANIA Douglas C

FISHERIES MANAGEMENT ON LAKE VICTORIA, TANZANIA Douglas C. Wilson Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association 4-7 Dec. 1993. Direct Correspondence to, Ecopolicy Center, Continuing Education Annex, PO Box 270, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ 08903 908-932-9583x15, fax 932-9544, [email protected] The author would like to acknowledge the support of: the Social Science Research Council's International Predissertation Fellowship Program; the Michigan State University African Studies Center; and the Tanzanian Fisheries Research Institute. Without the support and encouragement of these institutions this research would not have been possible. INTRODUCTION Lake Victoria is located in East Africa, on the equator, and is shared by Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. There are a number of current environmental problems associated with Lake Victoria and its basin. There has been a critical loss of biodiversity in the lake resulting from the introduction of exotic species. Pollution is a serious problem near the larger towns. Use of firewood in the processing of fish has made a significant contribution to the already sobering rates of deforestation in the lake basin and surrounding areas. The lake is suffering from a recent invasion of water hyacinth; an attractive, rapidly spreading, pernicious weed which blocks easy access to the lake while depleting oxygen needed by other species. While all of these problems are in need of sociological analysis this paper concentrates only on the problem of the over-fishing of the stocks of commercial fish species. The Lake Victoria fisheries are among the world's most important inland fisheries. Between 1975 and 1989 the lake fisheries produced a total value on the order of 280 million U.S. -

BANS, TESTS and ALCHEMY: FOOD SAFETY STANDARDS and the UGANDAN FISH EXPORT INDUSTRY Stefano Ponte DIIS Working Paper No 2005/19

DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES STRANDGADE 56 • 1401 COPENHAGEN K • DENMARK TEL +45 32 69 87 87 • [email protected] • www.diis.dk BANS, TESTS AND ALCHEMY: FOOD SAFETY STANDARDS AND THE UGANDAN FISH EXPORT INDUSTRY Stefano Ponte DIIS Working Paper no 2005/19 © Copenhagen 2005 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mails: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi as ISBN: 87-7605-104-8 Price: DKK 25,00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Stefano Ponte, Ph.D., is Senior Researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen. He can be reached at [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 2. The international regulatory framework governing exports of fish from Lake Victoria .............................................................................................................................................5 2.1 Main agreements and tariff barriers ...............................................................................................5 2.2 Non-tariff barriers ............................................................................................................................6 3. Uganda fisheries on Lake Victoria: a profile ...........................................................................9 -

Managment Implications Nakiyende H., Mbabazi D., Balirwa J.S., Bassa S., Muhumuza E., Mpomwenda V., Mangeni S.R., Mulowoza A., Mudondo P., Nansereko F., and Taabu A.M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons FISHING EFFORT AND FISH YIELD OVER A 15 YEAR PERIOD ON LAKE VICTORIA, UGANDA: Managment Implications Nakiyende H., Mbabazi D., Balirwa J.S., Bassa S., Muhumuza E., Mpomwenda V., Mangeni S.R., Mulowoza A., Mudondo P., Nansereko F., and Taabu A.M. 2016 ISSUE 1, VOL. I NKATA one of the Mukene landing sites on Lake Victoria he National Fisheries Resources Introduction and methodological problems TResearch Institute (NaFIRRI), the involved in obtaining reliable Directorate of Fisheries Resources (DiFR), catch and effort data to input in The fisheries of Lake Victoria the Local Government fisheries staff and the needed management advice. have for several decades those from the Beach Management Units contributed to the livelihoods (BMUs) of the riparian districts to Lake However, from 2000, FSs and and economic development in Victoria regularly and jointly conduct CASs methodologies were the riparian states of Kenya, Frame and Catch Assessment Surveys. introduced and harmonized on Tanzania and Uganda. The lake The information obtained is used to guide Lake Victoria under the Lake supports livelihoods of about fisheries management and development. Victoria Fisheries Organization four million people who depend (LVFO); the two methodologies on it directly for water, food, We reveal the trends in the commercial have become popular fish and employment and six million fish catch landings and fishing effort on stock assessment tools in the people indirectly. The lake the Uganda side of Lake Victoria, over a three riparian countries Kenya, fisheries contribute between 15 year period (2000-2015) and provide Tanzania and Uganda and are 3–6% of the national GDPs of the underlying factors to the observed regularly used to monitor and the three states (World Bank, changes. -

Rastrineobola Argentea) Fishery

Evolution and management of the mukene (Rastrineobola argentea) fishery Item Type monograph Authors Wandera, S.B. Publisher National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI) Download date 26/09/2021 11:23:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/34552 lJ~.···· )A0 4 4.6. Evolution' and management of themukene(Rastrineobola argentea) fishery Wandera S. B. Fisheries Resources Research Institute P.O. Box 343 Jinja, Uganda E-mail [email protected] Introduction Rastrineobola argentea locally known as mukene in Uganda, omena in Kenya and dagaa in Tanzania occurs in Lake Nabugabo, Lake Victoria, the Upper Victoria Nile and Lake Kyoga (Greenwood, 1966). While its fishery is well established on Lakes Victoria and Kyoga, the species is not yet being exploited on Lake Nabugabo. Generally such smaller sized fish species as R. argentea become important commercial species in lakes where they occur when catches of preferred larger-sized table fish start showing signs of decline mostly as a result of overexploitation. With the current trends of· . declining fish catches on Lake Nabugabo, human exploitation of mukene on this lake is therefore just a matter of time. The species is exploited both for direct· human consumption and as the protein ingredient in the manufacture of animal feeds. The introduction and subsequent establishment of the Nile perch Lates niloticus, and the Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, resulted into the disappearance of many native species from Lakes Victoria and Kyoga, through predation and competition for space (Ogutu Ohwayo, 1994, Witte et ai, 1992). R. argentea is presently the only indigenous fish species under commercial exploitation in these lakes. -

Regional Approach to Management of the Shared Fisheries Resources of Lake Victoria by the East Africa – Kenya, Uganda and Tanz

Management of Shared Inland Fisheries: Lessons from Lake Victoria (East Africa) Ogutu-Ohwayo, R. & C.T. Kirema Mukasa. Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization, P.O. Box 1625, Jinja, Uganda Email: [email protected] A paper prepared for Sharing of The Fish Conference 06, Espelanade Hotel, Fremantle, Perth, Western Australia. 23rd February – 2 March 2006 Abstract Africa has many large lakes most of which are shared between more than one country. One of them, Lake Victoria (68,000 km2) is shared between three East African Community (EAC) Partner States with 6% of the lake in Kenya, 43% in Uganda and 51% in Tanzania. The lake has a very lucrative fishery yielding 750,000m.t of fish valued at US$ 400 million annually. Fish exports from the lake earn Partner States US$ 250 million annually, and about 3 million out of 30 million people in the lake basin depend on the lake fisheries directly or indirectly for their livelihood. Management of the fisheries of Lake Victoria poses a challenge partly because management of the fisheries is by national governments under national jurisdictions. How then have the Partner States managed to harmoniously exploit the fisheries of the lake under multiple jurisdictions? The Partner States established a regional institution, the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization (LVFO) to harmonize national measures, and to develop and adopt conservation and management measures for sustainable utilization of the fisheries. National measures are harmonized into regional measures and agreed upon through the structures from the national village level to a Ministerial regional level. The LVFO then developed programs and formed Working Groups (WGs) at national and regional levels through which different activities are implemented. -

Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization and Fao Regional Stakeholders’ Workshop on Fishing Effort and Capacity on Lake Victoria

FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report No. 818 FIEP/R818 (En) ISSN 2070-6987 Report of the LAKE VICTORIA FISHERIES ORGANIZATION AND FAO REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS’ WORKSHOP ON FISHING EFFORT AND CAPACITY ON LAKE VICTORIA Mukono, Republic of Uganda, 8 November 2006 Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: Sales and Marketing Group Communication Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +39 06 57053360 Web site: http://www.fao.org FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report No. 818 FIEP/R818 (En) Report of the LAKE VICTORIA FISHERIES ORGANIZATION AND FAO REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS’ WORKSHOP ON FISHING EFFORT AND CAPACITY ON LAKE VICTORIA Mukono, Republic of Uganda, 8 November 2006 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2008 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISSN 978-92-5-106084-1 All rights reserved. -

Synthesis Report on Fisheries Research and Management Tanzania

LAKE VICTORIA ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT PROJECT (LVEMP) SYNTHESIS REPORT ON FISHERIES RESEARCH AND MANAGEMENT TANZANIA Prepared by Prof Y.D. Mgaya National Consultant November , 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. ii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS...................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... xi CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................... 1 1.2 History ................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project ................................ 3 1.2.2 Fisheries Research and Management and Components of LVEMP ..... 4 1.3 Objectives of LVEMP and Justification of the Present Consultancy ............ 5 CHAPTER TWO ............................................................................................................... 8 HISTORICAL TRENDS IN FISHERIES RESEARCH