A Social Analysis of Contested Fishing Practices in Lake Victoria, Tanzania”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin

A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY LAKE VICTORIA BASIN COMMISSION A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin © Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) Lake Victoria Basin Commission P.O. Box 1510 Kisumu, Kenya African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS) P.O. Box 459178-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Printed and bound in Kenya by: Eyedentity Ltd. P.O. Box 20760-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A Study on Aquatic Biodiversity in the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya: ACTS Press, African Centre for Technology Studies, Lake Victoria Basin Commission, 2011 ISBN 9966-41153-4 This report cannot be reproduced in any form for commercial purposes. However, it can be reproduced and/or translated for educational use provided that the Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) is acknowledged as the original publisher and provided that a copy of the new version is received by Lake Victoria Basin Commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Copyright i ACRONYMS iii FOREWORD v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi 1. BACKGROUND 1 1.1. The Lake Victoria Basin and Its Aquatic Resources 1 1.2. The Lake Victoria Basin Commission 1 1.3. Justification for the Study 2 1.4. Previous efforts to develop Database on Lake Victoria 3 1.5. Global perspective of biodiversity 4 1.6. The Purpose, Objectives and Expected Outputs of the study 5 2. METHODOLOGY FOR ASSESSMENT OF BIODIVERSITY 5 2.1. Introduction 5 2.2. Data collection formats 7 2.3. Data Formats for Socio-Economic Values 10 2.5. Data Formats on Institutions and Experts 11 2.6. -

By Martin Sturmer First Published by Ndanda Mission Press 1998 ISBN 9976 63 592 3 Revised Edition 2008 Document Provided by Afrika.Info

THE MEDIA HISTORY OF TANZANIA by Martin Sturmer first published by Ndanda Mission Press 1998 ISBN 9976 63 592 3 revised edition 2008 document provided by afrika.info I Preface The media industry in Tanzania has gone through four major phases. There were the German colonial media established to serve communication interests (and needs) of the German administration. By the same time, missionaries tried to fulfil their tasks by editing a number of papers. There were the media of the British administration established as propaganda tool to support the colonial regime, and later the nationalists’ media established to agitate for self-governance and respect for human rights. There was the post colonial phase where the then socialist regime of independent Tanzania sought to „Tanzanianize“ the media - the aim being to curb opposition and foster development of socialistic principles. There was the transition phase where both economic and political changes world-wide had necessitated change in the operation of the media industry. This is the phase when a private and independent press was established in Tanzania. Martin Sturmer goes through all these phases and comprehensively brings together what we have not had in Tanzania before: A researched work of the whole media history in Tanzania. Understanding media history in any society is - in itself - understanding a society’s political, economic and social history. It is due to this fact then, that we in Tanzania - particularly in the media industry - find it plausible to have such a work at this material time. This publication will be very helpful especially to students of journalism, media organs, university scholars, various researchers and even the general public. -

Fish, Various Invertebrates

Zambezi Basin Wetlands Volume II : Chapters 7 - 11 - Contents i Back to links page CONTENTS VOLUME II Technical Reviews Page CHAPTER 7 : FRESHWATER FISHES .............................. 393 7.1 Introduction .................................................................... 393 7.2 The origin and zoogeography of Zambezian fishes ....... 393 7.3 Ichthyological regions of the Zambezi .......................... 404 7.4 Threats to biodiversity ................................................... 416 7.5 Wetlands of special interest .......................................... 432 7.6 Conservation and future directions ............................... 440 7.7 References ..................................................................... 443 TABLE 7.2: The fishes of the Zambezi River system .............. 449 APPENDIX 7.1 : Zambezi Delta Survey .................................. 461 CHAPTER 8 : FRESHWATER MOLLUSCS ................... 487 8.1 Introduction ................................................................. 487 8.2 Literature review ......................................................... 488 8.3 The Zambezi River basin ............................................ 489 8.4 The Molluscan fauna .................................................. 491 8.5 Biogeography ............................................................... 508 8.6 Biomphalaria, Bulinis and Schistosomiasis ................ 515 8.7 Conservation ................................................................ 516 8.8 Further investigations ................................................. -

Threats to the Nyando Wetland CHAPTER 5

Threats to the Nyando Wetland. Item Type Book Section Authors Masese, F.O.; Raburu, P.O.; Kwena, F. Publisher Kenya Disaster Concern & VIRED International & UNDP Download date 26/09/2021 22:39:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/7415 CHAPTER 5 Threats to the Nyando Wetland Masese F.O., Raburu P.O and Kwena F. Summary All over the world, wetlands are hot spots of biodiversity and as a result they supply a plethora of goods and services to people living within them and in their adjoining areas. As a consequence, increased human pressure pose the greatest challenge to the well-being of wetlands, with Climate Change and nutrient pollution becoming increasingly important. Globally, the processes that impact on wetlands fall into five main categories that include the loss of wetland area, changes to the water regime, changes in water quality, overexploitation of wetland resources and introductions of alien species. Overall, the underlying threat to wetlands is lack of recognition of the importance of wetlands and the roles they play in national economies and indigenous peoples’ livelihoods. Wetlands form a significant component of the land area; covering around 6% of the land area. However, many of the wetlands have been degraded because of a combination of socioeconomic factors and lack of awareness compounded by lack of frameworks and guidelines for wetland conservation and management. In the Nyando Wetland, major threats include encroachment by people and animals for agriculture, settlement and grazing, overharvesting of papyrus, droughts, fire (burning), soil erosion in the uplands that cause siltation in the wetlands, invasion by alien species such as Mimosa pudica and water hyacinth Eichornia crassipes, and resource use conflicts. -

Transactional Fish-For-Sex Relationships Amid Declining Fish Access in Kenya

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Transactional Fish-for-Sex Relationships Amid Declining Fish Access in Kenya Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2h4147m1 Journal World Development, 74(C) ISSN 0305-750X Authors Fiorella, KJ Camlin, CS Salmen, CR et al. Publication Date 2015-10-01 DOI 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California World Development Vol. 74, pp. 323–332, 2015 0305-750X/Ó 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.015 Transactional Fish-for-Sex Relationships Amid Declining Fish Access in Kenya KATHRYN J. FIORELLA a,b, CAROL S. CAMLIN c, CHARLES R. SALMEN b,d, RUTH OMONDI b, MATTHEW D. HICKEY b,c, DAN O. OMOLLO b, ERIN M. MILNER a, ELIZABETH A. BUKUSI e, LIA C.H. FERNALD a and JUSTIN S. BRASHARES a,* a University of California, Berkeley, USA b Organic Health Response, Mbita, Kenya c University of California, San Francisco, USA d University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA e Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Nairobi, Kenya Summary. — Women’s access to natural resources for food and livelihoods is shaped by resource availability, income, and the gender dynamics that mediate access. In fisheries, where men often fish but women comprise 90% of traders, transactional sex is among the strategies women use to access resources. Using the case of Lake Victoria, we employed mixed methods (in-depth interviews, n = 30; cross-sectional survey, n = 303) to analyze the influence of fish declines on fish-for-sex relationships. -

Fisheries Around Lake Victoria and Attendance of Girls in Secondary Schools of Nyangoma Division in Siaya County, Kenya

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318658139 Fisheries around Lake Victoria and Attendance of Girls in Secondary Schools of Nyangoma Division in Siaya County, Kenya Article · June 2017 DOI: 10.15580/GJER.2017.4.061817076 CITATIONS READS 0 4 3 authors: Humphrey Musera Lugonzo Fatuma Chege Kenyatta University Kenyatta University 3 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS 33 PUBLICATIONS 113 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Violet Wawire Kenyatta University 7 PUBLICATIONS 3 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Teachers' preparedness for digital learning. View project Research Consortium on the Outcomes of Education and Poverty (RECOUP) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Fatuma Chege on 30 September 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ISSN: 2276-7789 ICV: 6.05 Submitted: 18/06/2017 Accepted: 22/06/2017 Published: 28/06/2017 Subject Area of Article: Education DOI: http://doi.org/10.15580/GJER.2017.4.061817076 Fisheries around Lake Victoria and Attendance of Girls in Secondary Schools of Nyangoma Division in Siaya County, Kenya By Humphrey Musera Lugonzo Fatuma Chege Violet Wawire Greener Journal of Educational Research ISSN: 2276-7789 ICV: 6.05 Vol. 7 (4), pp. 037-048, June 2017. Research Article (DOI: http://doi.org/10.15580/GJER.2017.4.061817076 ) Fisheries around Lake Victoria and Attendance of Girls in Secondary Schools of Nyangoma Division in Siaya County, Kenya *1 Humphrey Musera Lugonzo, 2Fatuma Chege, & 3Violet Wawire Department of Educational Foundations, School of Education, Kenyatta University, P.O. -

Illegal Fishing on Lake Victoria How Joint Operations Are Making an Impact December 2016

STOP ILLEGAL FISHING CASE STUDY SERIES 12 Illegal fishing on Lake Victoria How joint operations are making an impact December 2016 Background Many initiatives have been undertaken – especially in the Lake Victoria is an important source area of monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) – to of freshwater fish, contributing address the challenges of illegal fishing on Lake Victoria. significantly to the economies of For example, community-based Beach Management Units Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda and the 3 livelihoods and nutrition of three million (BMUs) have been established to legally represent each people. fishing community and undertake MCS activities; an MCS Nile perch, introduced in the 1950s, Regional Working Group (RWG-MCS) has been established became the most important species in to coordinate MCS activities; and the industrial fish the lake decimating the endemic fish processors exercise self-regulation in order to sustain their and, creating a lucrative commercial exports. However the problem continues, to an extent due fishery. Over-fishing and the use of destructive fishing gear has reduced to a lack of equipment and financing as well as technical the stock of larger, legal sized Nile capacity to implement MCS operations. perch1, resulting in the illegal trade of undersized fish. The Chinese market Faced with a continuing decline in the Nile perch stocks, for dried swim bladders has removed the LVFO Council of Ministers asked the SmartFish spawners from the stock, further Programme to work with all three member states to affecting its ability to recover. strengthen MCS of the lake fisheries. This took the form of The Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization capacity building in the first year, to develop professional (LVFO) was formed in 1994, but illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) MCS teams, followed by practical operations for the fishing continues to have a severe remaining three years. -

Hartford's Low-Income Latino Immigrants

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2013 Accessing Human Rights Through Faith-based Social Justice and Cultural Citizenship: Hartford's Low-income Latino Immigrants. Sarah C. Kacevich Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Social Welfare Commons Recommended Citation Kacevich, Sarah C., "Accessing Human Rights Through Faith-based Social Justice and Cultural Citizenship: Hartford's Low-income Latino Immigrants.". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/322 Kacevich 1 "Accessing Human Rights Through Faith-based Social Justice and Cultural Citizenship: Hartford's Low-income Latino Immigrants" A Senior Thesis presented by: Sarah Kacevich to: The Human Rights Studies Program, Trinity College (Hartford, Connecticut) April 2013 Readers: Professor Janet Bauer and Professor Dario Euraque In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the major in Human Rights Studies Kacevich 2 Abstract: Many low-income Latino immigrants in Hartford lack access to the human rights to education, economic security, and mental health. The U.S. government’s attitude is that immigrants should be responsible for their own resettlement. Catholic Social Teaching establishes needs related to resettlement as basic human rights. How do Jubilee House and Our Lady of Sorrows, both Catholic faith-based organizations in Hartford, Connecticut, fill in the gaps between state-provided services and the norms of human rights? What are the implications of immigrant accommodation via faith-based social justice for the human rights discourse on citizenship and cultural relevance? A formal, exploratory case study of each of these FBOs, over a 3-month period, provide us with some answers to these questions. -

University of Birmingham the Political Economy of Fisheries Co-Management

University of Birmingham The political economy of fisheries co-management Nunan, Fiona DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102101 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Nunan, F 2020, 'The political economy of fisheries co-management: challenging the potential for success on Lake Victoria', Global Environmental Change, vol. 63, 102101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102101 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

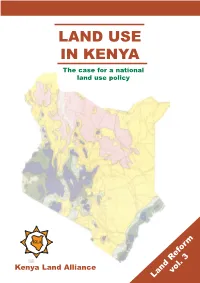

LAND USE in KENYA the Case for a National Land Use Policy

landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page i LAND USE IN KENYA The case for a national land use policy Kenya Land Alliance ol. 3 v Land Reform landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page ii II Credits Published by: Kenya Land Alliance Printing House Road PO Box 7150, Nakuru Tel: +254 37 41203 Email: [email protected] Text by: Consultants for Natural Resources Management PO Box 62702, Nairobi Tel: +254 2 723958; 0733-747677 Fax: +254 2 729607 Email: [email protected] Edited By: Ms. Dali Mwagore PO Box 30677, Nairobi Design and Layout: Creative Multimedia Communications Limited PO Box 56196, Nairobi Tel: +254 2 230048 ISBN 9966-896-92-2 Printed by: Printfast Kenya Limited PO Box Nairobi Tel: 557051 Land Use in Kenya • The case for a national land-use policy landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page iii Cover iii Alpine moorland (water catchments) Humid (intensive agriculture/forestry) Humid (intensive mixed farming) Semi-humid (mixed dryland farming) Semi-arid (pastoralism/wildlife) Arid (nomadic pastoralism) Land Use in Kenya • The case for a national land-use policy landUse4.1 2/22/02 10:29 AM Page iv iv Contents Contents Acknowledgement vi Preface vii Summary viii Acronyms ix Introduction: Land use in Kenya 2 Chapter One: Land resources in Kenya 1.1 Agricultural land potential 5 1.2 Forest resources 10 1.3 Savannahs and grasslands 15 1.4 Water resources 20 1.5 Fisheries 25 1.6 Wetlands 27 1.7 Wildlife resources 29 1.8 Mineral resources 31 1.9 Energy 33 Chapter Two: Land abuse in Kenya 2.1 Soil erosion 37 2.2 Pollution 42 2.3 The polluting agents 44 2.4 Urban -

The Fishesof Uganda-I

1'0 of the Pare (tagu vaIley.': __ THE FISHES OF UGANDA-I uku-BujukUf , high peaks' By P. H. GREENWOOD Fons Nilus'" East African Fisheries Research Organization ~xplorersof' . ;ton, Fresh_ CHAPTER I I\.bruzzi,Dr: knowledge : INTRODUCTION ~ss to it, the ,THE fishes of Uganda have been subject to considerable study. Apart from .h to take it many purely descriptive studies of the fishes themselves, three reports have . been published which deal with the ecology of the lakes in relation to fish and , fisheries (Worthington (1929a, 1932b): Graham (1929)).Much of the literature is scattered in various scientific journals, dating back to the early part of the ; century and is difficult to obtain iIi Uganda. The more recent reports also are out of print and virtually unobtainable. The purpose .of this present survey is to bring together the results of these many researches and to present, in the light of recent unpublished information, an account of the taxonomy and biology of the many fish species which are to be found in the lakes and rivers of Uganda. Particular attention has been paid to the provision of keys, so that most of the fishesmay be easily identified. It is hardly necessary to emphasize that our knowledge of the East African freshwater fishes is still in an early and exploratory stage of development. Much that has been written is known to be over-generalized, as conclusions were inevitably drawn from few and scattered observations or specimens. From the outset it must be stressed that the sections of this paper dealing with the classification and description of the fishes are in no sense a full tax- onomicrevision although many of the descriptions are based on larger samples than were previously available. -

INTERPOL Study on Fisheries Crime in the West African Coastal Region

STUDY ON FISHERIES CRIME IN THE WEST AFRICAN COASTAL REGION September 2014 Acknowledgements The INTERPOL Environmental Security Sub-Directorate (ENS) gratefully received contributions for the contents of this study from authorities in the following member countries: . Benin . Cameroon . Cape Verde . Côte d’Ivoire . The Gambia . Ghana . Guinea . Guinea Bissau . Liberia . Mauritania . Nigeria . Senegal . Sierra Leone . Togo And experts from the following organizations: . Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) . European Commission . Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea (FCWC) . Hen Mpoano . International Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) Network . International Maritime Organization (IMO) . Maritime Trade Information Sharing Centre for the Gulf of Guinea (MTISC-GoG) . Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) . Norwegian National Advisory Group Against Organized IUU-Fishing . The Pew Charitable Trusts . Stop Illegal Fishing . Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC) . United States Agency for International Development / Collaborative Management for a Sustainable Fisheries Future (USAID / COMFISH) . United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . World Customs Organization (WCO) . World Bank This study was made possible with the financial support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photograph: Copyright INTERPOL. Acknowledgements Chapter: Chapter: 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................