Hartford's Low-Income Latino Immigrants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sparta Channel Lineup

Optimum Premier Includes Optimum Select Optimum College Sports Pack Premium Channels Effective April 2021 79 UP HD 579 121 Fox College Sports Atlantic 344 Showtime Showcase 119 TVG Network 122 Fox College Sports Central 345 Showtime Women 320 HBO HD 570 123 Fox College Sports Pacific 346 Showtime Next 321 HBO Family 347 Showtime Family Zone Optimum Sports Pack 322 HBO Latino HD 662 348 Showtime West HD 671 Sparta 323 HBO2 HD 661 102 Fight Network HD 602 349 Showtime 2 West HD 672 324 HBO Signature 103 Game+ HD 614 350 Showtime Showcase West 325 HBO Comedy 105 World Fishing Network HD 617 351 The Movie Channel HD 573 Channel 326 HBO Zone 106 Sportsman Channel HD 618 352 The Movie Channel Xtra 327 HBO West HD 663 107 MavTV Motorsport Network HD 619 353 The Movie Channel West HD 675 Lineup 328 HBO2 West HD 664 108 Gol TV (English) 354 The Movie Channel Xtra West 329 HBO Family West 114 Willow 360 Starz Encore 330 HBO Signature West 116 NHL Network HD 616 361 Starz Encore Action + Broadcast Basic 340 Showtime HD 572 119 TVG Network 363 Starz Encore Black 341 Showtime Extreme 130 NFL Red Zone HD 601 365 Starz Encore Classic + Optimum Core 342 Showtime 2 HD 670 Premium Channels 367 Starz Encore Suspense + Optimum Select 343 SHOxBET 369 Starz Encore Westerns 344 Showtime Showcase 270 – 283 MLB Extra Innings (HD Only) 371 Starz Encore West + Optimum Premier 345 Showtime Women 270 – 283 NHL Center Ice (HD Only) 372 Starz Encore Family + Optimum Sports Pack 346 Showtime Next 320 HBO HD 570 373 Starz Encore Espanol + 347 Showtime Family Zone 321 -

Guide to U.S. Government Export Programs and Resources for Trade and Investment

GUIDE TO U.S. GOVERNMENT EXPORT PROGRAMS AND RESOURCES FOR TRADE AND INVESTMENT International markets are an essential part of many companies’ growth strategies. Having expert knowledge and meaningful support available at all stages of the international buying and selling process, from initial efforts to identify potential markets all the way to factoring receipts, can mean the difference between a thriving business and one that never quite gets off the ground. The United States Government (USG) offers a variety of resources to African and United States companies that want to trade with and invest in one another’s markets. This document is a “one-stop shop” that outlines the major USG programs and resources available to these companies. It also provides links, brief descriptions, and comments to help companies decide if a resource might be useful. This guide also provides brief capsule descriptions of the principal USG departments and agencies involved in international trade and development. These descriptions can help businesspeople understand the different roles that these entities play in international trade. MAY 2011 This brief was produced by SEGURA Partners, LLC for review by the U.S. Agency of International Development, U.S. trade agencies, and USAID-sponsored African trade hubs. It was prepared by Knowledge Sharing & Analysis project Senior Technical Advisor Paxton Helms. GUIDE TO U.S. GOVERNMENT EXPORT PROGRAMS AND RESOURCES FOR TRADE AND INVESTMENT 1 QUICK HITS FOR AFRICAN EXPORTERS AND U.S. IMPORTERS USAID-funded Trade Hubs can provide African companies with technical assistance, information, and contacts to help them begin or expand their export business. -

May 24, 2020 Seventh Sunday of Easter

Making Disciples through Prayer, Faith Formation and Service Pastoral Staff Rev. James Wood - Pastor x111 [email protected] Rev. Paul Butler - Pastoral Vicar x118 [email protected] Deacons - Ed Hayes x0 Retired: William Kogler, Biagio Muratore, Parish Center Office – Receptionist x0 Julie Burtoff, Admin Assistant x133 [email protected] Faith Formation Office Jackie Mirenda, Coordinator x131 [email protected] Business Manager Lisa Boyd x113 [email protected] Music Ministry Dr. Daniel Crews, Director x117 [email protected] Parish Outreach Seventh Sunday of Easter [email protected] Julie Burtoff, x119 Holy Angels Regional Catholic School May 24, 2020 Patchogue, NY 631-475-0422 Michael Connell, Principal Phone: (631) 732-3131 Celebration of the Eucharist During this time, the Parish Office is closed. Until further notice, Any meeting will be by appointment Only. there will be no public masses celebrated Fax (631) 732 - 8827 Confessions www.saintmargaret.com By appointment Only 81 COLLEGE ROAD SELDEN NY 11784-2813 Masses for the Week While no public masses are celebrated at this time, we will be saying masses for all the intentions arranged before the new Sue Callari Marjorie Boyd directives. Antone Straussner IV Charles Kunkel Monday - May 25th Katherine Petitto Marilyn Molloy Deceased Military from St Margaret’s Gerard Hodum Jonathan Hark Tuesday - May 26th Glenn Campbell Joe Vollmer No Intention Grace Iannotta Alfred Saracino Wednesday - May 27th Jean Sottile Charles Murray No Intention Eileen Helmken Louise Quinn Thursday, - May 28th No Intention Friday - May 29th No Intention Saturday - May 30th Antonia, Pasquale & Rosa Palumbo Sunday – May 31st All the Souls in Purgatory Helen Volpe Carol Ann Devivo-Ortiz All Parishioners With funeral homes being overly busy and not scheduling Funeral Masses, we are often not informed of the deaths of parishioners. -

Roman Catholic Church of St. Mark

105RRandallomanRoad • Shoreham,CatholNY 11786ic• 744-2Church800 • Fax 821-1628of• STMARKSRCC@AOSt. MarkL.COM stmarksrcc-shoreham.org THE PASTORAL STAFF REV. LENNARD SABIO, Parish Administrator REV. THOMAS TUITE, Associate Pastor Permanent Deacons 744-2800 Rev. Mr. Patrick Gerace Rev. Mr. Gino Aceto, [email protected] Office Manager: 744-2800 Mrs. Susan Schena Parish Outreach: 744-2800 Mrs. Jane Fagan, Coordinator, FaithFormation: 821-0550 Mrs. Lynn Fein, Director, [email protected] Music Director: 821-8497 Mrs. Carrie Logan, [email protected] Youth Ministry for 7th-12th graders: 744-2800 Mrs. Lynn Fein, [email protected] Mr. John McNamara, [email protected] ACTS 744-2800 Mrs. Jane Fagan March 22, 2020 - Fourth Sunday of Lent MASSES: BAPTISMS: The parish community celebrates this SATURDAY EVENING: 5:00 P.M. sacrament at 1:00 P.M. on the third Saturday of each month. SUNDAYS: 8:00, 9:30, 11:30 A.M. Please contact the rectory before your child is born to make WEEKDAYS: Monday-Friday 9:00 A.M. arrangements for the Pre-Baptism program. HOLY DAYS: Vigil 7:30 P.M. (Day) 9:00, 10:30 A.M. ANOINTING OF THE SICK: Periodically we have a RECTORY OFFICE HOURS: parish celebration. However if you or someone in your Monday thru Friday: 9:30A.M. - 5:00 P.M. family is seriously ill or going to the hospital for a serious Closed for lunch from 12:00 Noon till 1:00 P.M. operation, then call the rectory. Anyone going to a hospital Saturday: by appointment only or who may be sick at home should inform the rectory so Sunday: closed the parish can pray for you. -

CHRISTIANITY of CHRISTIANS: an Exegetical Interpretation of Matt

CHRISTIANITY OF CHRISTIANS: An Exegetical Interpretation of Matt. 5:13-16 And its Challenges to Christians in Nigerian Context. ANTHONY I. EZEOGAMBA Copyright © Anthony I. Ezeogamba Published September 2019 All Rights Reserved: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN: 978 – 978 – 978 – 115 – 7 Printed and Published by FIDES MEDIA LTD. 27 Archbishop A.K. Obiefuna Retreat/Pastoral Centre Road, Nodu Okpuno, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State, Nigeria (+234) 817 020 4414, (+234) 803 879 4472, (+234) 909 320 9690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fidesnigeria.com, www.fidesnigeria.org ii DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to my dearest mother, MADAM JUSTINA NKENYERE EZEOGAMBA in commemoration of what she did in my life and that of my siblings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the handiwork of God in my life who is the author of my being. I am grateful to Most Rev. Dr. S.A. Okafor, late Bishop of Awka diocese who gave me the opportunity to study in Catholic Institute of West Africa (CIWA) where I was armed to write this type of book. I appreciate the fatherly role of Bishop Paulinus C. Ezeokafor, the incumbent Bishop of Awka diocese together with his Auxiliary, Most Rev. Dr. Jonas Benson Okoye. My heartfelt gratitude goes also to Bishop Peter Ebele Okpalaeke for his positive influence in my spiritual life. I am greatly indebted to my chief mentor when I was a student priest in CIWA and even now, Most Rev. -

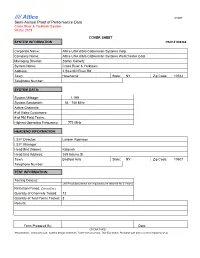

Proof of Performance Data Cross River & Yorktown System Winter 2019

//// Altice CV001 CV001 Semi-Annual Proof of Performance Data Cross River & Yorktown System Winter 2019 COVER SHEET SYSTEM INFORMATION PSID # 008368 Corporate Name: Altice USA d/b/a Cablevision Systems Corp. Company Name: Altice USA d/b/a Cablevision Systems Westchester Corp Managing Director: Stefan Gallwitz System Name: Cross River & Yorktown Address: 2 Saw Mill River Rd Town: Hawthorne State: NY Zip Code: 10532 Telephone Number: SYSTEM DATA: System Mileage: 1,199 System Bandwidth: 54 - 750 MHz Active Channels: # of Video Customers: # of PM Field Techs: Highest Operating Frequency: 771 MHz HEADEND INFORMATION: I.S.P. Director: Larawn Robinson I.S.P. Manager: Head End (Name): Katonah Head End Address: 389 Adams St Town: Bedford Hills State: NY Zip Code: 10507 Telephone Number: TEST INFORMATION: Testing Date(s): (All Proof documents are required to be retained for 5 Years) Retention Period: (Discard Date) Quantity of Channels Tested: 12 Quantity of Test Points Tested: 8 Results: Form Prepared By: Date: (SIGNATURE) Attachments: Community List, System design distortion, Test Point Locations, Test Equipment, Personnel List and a current channel Line up. //// Altice CV002 Semi-Annual Proof of Performance Data Cross River & Yorktown System Winter 2019 FCC Rules & Regulations, Subpart A - General, 76.5 (dd) Definitions, Community Unit . A cable television system, or portions of a cable television system that operates or will operate within a separate and distinct community or municipal entity. COMMUNITIES SERVED BY THIS HEADEND: (Franchise issuing Municipalities) PSID # 008368 C.U.I.D. # C.U.I.D. # (FCC Community I.D. #) Community Name (FCC Community I.D. #) Community Name NY0426 Bedford NY0427 Mount Kisco NY0942 Yorktown NY1056 North Castle NY1066 Somers NY1083 Putnam Valley NY1381 North Salem NY1382 Lewisboro NY1489 Pound Ridge //// Altice CV003 Semi-Annual Proof of Performance Data Cross River & Yorktown System Winter 2019 FCC Rules & Regulations, Subpart K - Technical Standards, 76.601(c) (1) Performance tests . -

Faculty & Administration News (FAN)

Faculty & Administration News (FAN) Volume XI, Issue 3 May 2020 First issued in November 2009, Faculty & Administration News (FAN) is a quarterly publication of Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology (ICSST). This newsletter highlights the most recent professional accomplishments and service activities of ICSST’s faculty and administrators. Click the hyperlinks to explore the work of our faculty and administrators. Award ❖ Jeffrey L. Morrow, Ph.D., Professor of Undergraduate Theology, was honored as a distinguished Seton Hall University faculty member, having been named Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology’s Researcher of the Year, in the Spring 2020 semester. Speaking Engagements ❖ Reverend Pablo T. Gadenz, S.S.L., S.T.D., Associate Professor of Biblical Studies, with Auxiliary Bishop Richard Henning of the Diocese of Rockville Centre, NY, served as co- host of the new “Living Word” television talk show series, on the Catholic Faith Network (operated by the Diocese of Rockville Centre, NY, and reaching television audiences in the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut area). This series focuses on the biblical foundations and themes of the liturgical year. Father Gadenz taped three episodes of this series at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, NYC, on March 2, 2020. The three episodes are as follows: o “The Lenten Season: Part I” (covers the beginning of Lent). o “The Lenten Season: Part II” (covers Holy Week). o “The Easter Season” (covers the Easter season, and began airing after Easter). All three shows are available for viewing online at the following website: https://www.catholicfaithnetwork.org/living-word. Future shows are currently planned to cover the Advent and Christmas seasons. -

Economic Impacts of Ghana's Political Settlement

DIIS working paper DIIS workingDIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:28 paper Growth without Economic Transformation: Economic Impacts of Ghana’s Political Settlement Lindsay Whitfield DIIS Working Paper 2011:28 WORKING PAPER 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:28 LINDSAY WHITFIELD is Associate Professor in Global Studies at Roskilde University, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank Adam Moe Fejerskov for research assistance, as well as the African Center for Economic Transformation for assistance in accessing data from the Bank of Ghana used in Figure 3 DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:28 © The author and DIIS, Copenhagen 2011 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Ellen-Marie Bentsen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-477-9 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2011:28 DIIS WORKING PAPER SUB-SERIES ON ELITES, PRODUCTION AND POVERTY This working paper sub-series includes papers generated in relation to the research programme ‘Elites, Production and Poverty’. This collaborative research programme, launched in 2008, brings together research institutions and universities in Bangladesh, Denmark, Ghana, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda and is funded by the Danish Consultative Research Committee for Development Research. -

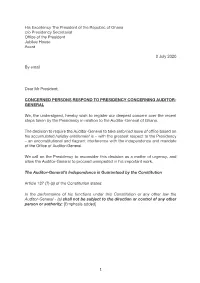

Auditor General.Pdf

His Excellency The President of the Republic of Ghana c/o Presidency Secretariat Office of the President Jubilee House Accra 8 July 2020 By email Dear Mr President, CONCERNED PERSONS RESPOND TO PRESIDENCY CONCERNING AUDITOR- GENERAL We, the undersigned, hereby wish to register our deepest concern over the recent steps taken by the Presidency in relation to the Auditor-General of Ghana. The decision to require the Auditor-General to take enforced leave of office based on his accumulated holiday entitlement is – with the greatest respect to the Presidency – an unconstitutional and flagrant interference with the independence and mandate of the Office of Auditor-General. We call on the Presidency to reconsider this decision as a matter of urgency, and allow the Auditor-General to proceed unimpeded in his important work. The Auditor-General’s Independence is Guaranteed by the Constitution Article 187 (7) (a) of the Constitution states: In the performance of his functions under this Constitution or any other law the Auditor-General - (a) shall not be subject to the direction or control of any other person or authority; [Emphasis added] 1 This provision is clear and unambiguous. The framers of our Constitution limited the President’s powers over the Auditor General to the power to “acting in accordance with the advice of the Council of State, request(ing) the Auditor-General in the public interest, to audit, at any particular time, the accounts of any (public) body or organisation as is referred to in clause (2) of this article (187).[1]” [Emphasis added]. Furthermore, the Constitution prescribes that the “The salary and allowances payable to the Auditor-General, his rights in respect of leave of absence, retiring award or retiring age shall not be varied to his disadvantage during his tenure of office”[2]. -

Residential Channel Lineup

Digital Tier Premium Channels STARZ ENCORE 360 Starz Encore East 107 MAV TV HD 619 MLB EXTRA INNINGS / NHL CENTER ICE 361 Starz Encore Action E 121 Fox Sports Atlantic 270 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 1 HD 122 Fox Sports Central 362 Starz Encore Action W 271 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 2 HD 123 Fox Sports Pacific 363 Starz Encore Black E 272 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 3 HD NFL Redzone HD 601 364 Starz Encore Black West 130 273 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 4 HD Residential 138 FUSE HD 610 365 Starz Encore Classic E 274 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 5 HD 139 MTV Hits 366 Starz Encore Classic W 275 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 6 HD 141 MTV2 367 Starz Encore Suspense East Channel 276 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 7 HD MTV Live HD 620 368 Starz Encore Suspense West 277 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 8 HD 142 VH1 Soul 369 Starz Encore Western E 278 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 9 HD Lineup 143 MTV TR3S 370 Starz Encore Western W 279 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 10 HD 144 CMT Music 371 Starz Encore West 280 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 11 HD 145 BET Jams 372 Starz Encore Family 281 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 12 HD 146 MTV Classic + Broadcast Basic 282 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 13 HD STARZ 147 BET Her 283 MLB Extra Innings /NHL Center Ice Game 14 HD 381 Starz East HD 568 + Expanded Basic 156 IFC HD 609 HBO 382 Starz West + 159 Hallmark Drama HD 659 Digital Tier 321 HBO HD 570 383 Starz Kids & Family 186 Fusion + Preferred Tier 322 HBO Family 384 Starz Cinema East 202 Cooking Channel HD 596 323 HBO Latino 385 Starz Cinema West + Premium Channels 217 Nick Jr. -

Primary Care Commissioning Committee Meeting Held in Public 18 May 2017, 9:30 Am – 12.30Pm Room 1, Jubilee House, Bloxwich Lane, Walsall, WS2 7JL

Primary Care Commissioning Committee Meeting held in public 18 May 2017, 9:30 am – 12.30pm Room 1, Jubilee House, Bloxwich Lane, Walsall, WS2 7JL Agenda Items Item No Assurance Decision Approval Information only 9.30 1.0 Introductions and apologies for absence* Carol Marston, Robert Freeman 9.35 2.0 Notification of any items of other business* 2.1 Declarations of interest* 9.40 3.0 Consent Agenda 9.40 3.1 To approve the Minutes of the Primary Care Item 3.1 Approval Commissioning Committee held on 20 April 2017. 9.45 3.2 IT Steering Group update Item 3.2 Information 9.45 3.3 Walsall Plan Item 3.3 Information 9.45 3.4 Public Health Transformation Fund Review Item 3.4 Information 9.45 3.5 Big Conversation Update ( full report available on Item 3.5 Information CCG internet ) 9.55 4.0 Report on Matters Arising – Action log Item 4.0 Discussion 10.00 4.1 Finance Report – TG Item 4.1 Information 10.05 4.2 QIPP Report Item 4.2 Information 4.3 - GB Medicines Management presentation Item 4.3 Information 4.4 - Medicines Management Business Case Item 4.4 Approval 10.10 5.0 PCOG Update Item 5.0 Information - Quality assurance update 10.20 6.0 Saturday Opening Evaluation Item 6.0 Information 10.25 7.0 Latent TB Screening Item 7.0 Information 10.35 8.0 Audit Response - DM Item 8.0 Information 10.40 9.0 Transformation funding bids - DM Item 9.0 Information 10.50 10.0 Risk Register Item 10.0 Information Any other business 10:55 11.0 11:00 12.0 Date of next meeting: 15 June 2017, 9.30am – Room 1, Jubilee House 11.00 13.0 Close *Monthly standing items on the agenda. -

St. James R.C. Church March 24, 2019 Third Sunday in Lent

St. James R.C. Church March 24, 2019 Third Sunday in Lent Weekday Masses Monday — Saturday: 8:00 am Sunday Masses Saturday: 5:00 pm (Youth) Sunday: 8:00 am, 9:30 am (Family), 11:30 am (Choir) Holy Days Vigil: 7:30 pm Day: 8:00am, 12 Noon Special Needs Mass: Second Saturday of the month at 1:00pm Nocturnal Adoration: First Friday of the Month, 7:30 -8:30pm Reconciliation Saturdays 4:00 — 4:45 pm or by appointment Rev. James -Patrick Mannion, Pastor [email protected] (ext. 322) Rev. Gerald Cestare, Associate Pastor [email protected] (ext. 321) Rev. John Fitzgerald , in residence Business Manager: Todd Bradshaw(ext.312) 429 Route 25A, Setauket, New York 11733 -3829 Parish Office: (631) 941.4141 Dir. of Outreach: Kathryn Vaeth (ext. 313) Fax: (631) 751.6607 Dir. of Faith Formation: Louise DiCarlo Faith Formation Office: (631) 751.7287 (ext. 329) Admin. Asst. Joanmarie Zipman (ext. 328) Email: [email protected] Music Co -Director: Website: www.stjamessetauket.org Office hours: M -F 9am -4pm (closed for lunch 12 -12:30) Richard Foley (631) 806.1794 Sat. 9am -2pm Music Co -Director: Miriam Salerno (516) 263.5173 “Be doers of the word and not hearers only ” James 1:22 Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA): Cris O ’Keefe (631) 751.2819 Parish Receptionists: 2019 Mission Statement: Megan Peters (M -F); Joan Murray (Sat) Formed as the Body of Christ through the waters of Baptism, we are Nancy Gallagher (weekdays and Sat) Beloved daughters and sons of the Father. We, the Catholic community Parish Facilities Supervisor: Jeff Fallon of the Three Village area, are a pilgrim community on Camino - Our Lady of Wisdom Regional School: journeying toward the fullness of the Kingdom of God, guided by the Holy Spirit.