QS World University Rankings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 351 190 SE 053 110 AUTHOR Forgasz, Helen, Ed. TITLE Research in Science Education. Volume 21. Selected Refereed Papers from the Annual Conference of the Australasian Science Education Research Association (22nd, Surfers Paradise, Queensland, Australia, July 11-14, 1991). INSTITUTION Australasian Science Education Research Association, Victoria (Australia). REPORT NO ISSN-0157-244X PUB DATE 91 NOTE 370p. AVAILABLE FROMFaculty of Education, School of Graduate Studies, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168, Australia. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Research in Science Education; v21 1991 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Concept Formation; Constructivism (Learning); *Educational Research; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Learning Strategies; *Science and Society; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; Science Instruction; *Sex Differences; *Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Australia; *Science Education Research ABSTRACT This annual publication contains 43 research papers on a variety of issues related to science education. Topics include the following: mature-age students; teacher professional development; spreadsheets and science instruction; the Learning in Science Project and putting it into practice; science discipline knowledge in primary teacher education; science, technology, and society; gender differences in choosing school subjects; history of science education; quality of -

A Comparative Study Between Brazil and Portugal

DOI: 10.36315/2019v2end027 Education and New Developments 2019 OVERVIEW OF DESIGN TEACHING ON ENGINEERING COURSES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN BRAZIL AND PORTUGAL Claudia Alquezar Facca1, Jorge Lino Alves2, & Ana Mae Barbosa3 1Engineering School, Mauá Institute of Technology (Brazil); PPG Design, Anhembi Morumbi University (Brazil); Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto (Portugal) 2INEGI, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto (Portugal) 3PPG Design, Anhembi Morumbi University (Brazil) Abstract This paper presents an overview of design teaching in the undergraduate engineering courses at the main institutions of higher education in Brazil and Portugal. In order to carry out the comparative study, the curricula of the main engineering courses in Brazil and Portugal were used. The aim of the research is to first analyze how the design, as a disciplinary content, is being introduced in the engineering courses in both countries. In a second moment, a comparative analysis will be made between the information collected in Brazil and in Portugal in order to register how this conjugation is occurring and whether there is some similarity or not in the way of design approach in the engineering courses in each country. As a result, it is discussed how the design can collaborate with the interdisciplinarity between these areas and contribute with the formation of the new competences of the engineer. Keywords: Education, design, engineering, Brazil, Portugal. 1. Introduction Education is the object of study, concern, focus, strategy and discussion in all the nations of the globe and reflects the intense changes the world has witnessed in the last decades of the 20th century, beginning with the two great wars, then the expansion of capitalism and the cultural and economic globalization in the 21th century. -

1 ATEM Council Agenda 22 May 2004

1 ATEM Council Agenda 22 May 2004 Association for Tertiary Education Management Inc. ABN 72 682 233 729 DRAFT COUNCIL AGENDA There will be a meeting of the ATEM Council on Saturday 22 May from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm at the Wentworth Street Travelodge, Darlinghurst, Sydney. The Venue is the Wentworth Room on the lower ground floor. The meeting will be followed by a Thai dinner in China Town. The meeting will be preceded by a meeting of the ATEM Executive Committee, John Mullarvey and Susan Scott of the AVCC and Linda McLain, Chair, Professional Education and Training Group, including lunch, on Friday 21 May 2004. For the information of your office, the phone and fax numbers of the Travelodge are: Tel: 61 2 8267 1700, Fax: 61 2 8267 1800. Please tell Giles Pickford if you wish to change your accommodation booking. 1 Welcome and Apologies The President will welcome Lucy Schulz, President of the South Australian Branch, to her first meeting. *2 Starring of Items The President will invite members to star any additional items for discussion. All unstarred items will then be immediately and simultaneously received, endorsed, approved or noted as appropriate. 3 Minutes The following Minutes have been distributed and are on the web. For confirmation 3.1 The Minutes of the Council Meeting held on Sunday 28 September 2003 in the Hilton Hotel, Adelaide. The following minutes are attached for noting: 3.2 The Flying Minute on Council Standing Orders was adopted by Council Flying Minute 03/38 in November 2003. 3.3 The Flying Minutes on Membership Matters was adopted by Council Flying Minute 03/39 in October 2003. -

2020 Yearbook

2020 YEARBOOK 1 QS World University Rankings 2020 Yearbook Published by QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 1 Tranley Mews, Fleet Road, London NW3 2DG United Kingdom qs.com 1st edition, May 2020 Book ISBN: 978-981-14-5329-8 eBook ISBN: 978-981-14-5330-4 Copyright © QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited 2020 All rights reserved. The entire content of this publication is protected by international copyright. No part of it may be copied or reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any permitted reproduction of QS Rankings data must be sourced: QS World University Rankings® 2020. Any other permitted reproduction must be sourced: QS World University Rankings 2020 Yearbook, QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited 2020. For permission, please write to Monica Hornung Cattan [email protected] Acknowledgements QS would like to thank the advertisers in this edition, the main editorial contributors (see page 9), and the many other QS and external colleagues who have contributed, particularly including the QS Intelligence Unit team behind the QS World University Rankings®: Ben Sowter, Jason Newman, Leigh Kamolins, Monica Hornung Cattan, Anton John Crace, Samuel Ang, Ana Marie Banica, Effie Chen, E Way Chong, Juan Carlos Mejia Cuartas, Alloysius Ching, Alex Chisholm, Ashwin Fernandes, Tony Fregoli, Selina Griffin, Ludovic Highman, Elena Ilie, Daniel Kahn, Yea Yin Kek, Taewan Kim, Andrew MacFarlane, Gabriel Maschião da Costa, David Myers, Larisa Osipova, Ajita Rane, Shiloh Rose, Nicholas Sequeira, Rashmi Sharma, Padmashree Sorate, Violeta Surugiu, Ken Trinh, Jia Ying Wong, Samuel Wong, Yuh Ming Yap, Dennis Yu, Zoya Zaitseva. -

Second Circular Conference Colombia in the IYL 2015

SECOND ANNOUNCEMENT International Conference \Colombia in the International Year of Light" June 16 - 19, 2015 Bogot´a& Medell´ın,Colombia 1 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Dear Colleagues, The International Conference Colombia in the International Year of Light (IYL- ColConf2015) will be held in Bogot´a,Colombia on 16-17 June 2015, and Medell´ın, Colombia on 18-19 June 2015. IYLColConf2015 is expected to bring together 500- 600 scientists, other professionals, and students engaged to research, development and applications of science and technology of light. You are invited to attend this conference and take part in the discussions about the \state of the art" in this field, in company of world-renowned scientists. Organizers and promoters of this conference include: The Universidad de los Andes (University of the Andes), Bogot´a;the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (National University of Colombia), Bogot´aand Medell´ın; the Universidad de Antioquia (University of Antioquia), Medell´ın; the Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales (Colombian Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences); Colombian research groups working on topics related to optical sciences, and academic programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We are honored to host IYLColConf2015 in Bogot´aand Medell´ın,two of the main cities of Colombia, in June 2015. We look forward to seeing you there. Sincerelly yours, On behalf of the Executive Committee, Prof. Jorge Mahecha. Institute of Physics, Universidad de Antioquia. page 2 of 27 http://indico.cern.ch/e/iyl2015colombiaconf• International Conference Colombia in the IYL Contents • IYLColConf2015 Committees 3 • General Information and Deadlines 5 • Registration and Support Policy 7 • Further Information 8 • Scientific Program 9 • Conference proceedings 25 • Travel and Transportation 25 • Hotels and Accommodations 25 • Miscellaneous 25 • Sponsors 27 IYLColConf2015 Committees International Advisory Committee Prof. -

Austria University of Vienna All Belgium Catholic University Of

Monash University - Exchange Partners Faculties Minimum GPA/WAM Austria University of Vienna All WAM 65 Belgium Catholic University of Leuven BusEco WAM 70 Brazil Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) of Rio de Janeiro All WAM 70 Brazil Universidade de Brasilia All WAM 70 Brazil State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) Brazil All WAM 70 Brazil University of Sao Paulo Arts WAM 70 Canada Bishop's University All WAM 70 Canada Carleton University All WAM 70 Canada HEC Montreal BusEco GPA 3.0 Canada Queen's University Arts, Science, Engineering, BusEco GPA 2.7 Canada Simon Fraser University All WAM 70 Canada University of British Columbia All except BusEco & Law WAM 85 Canada University of Ottawa BusEco WAM 70 Canada University of Waterloo All WAM 70 Canada York University All except BusEco & Law WAM 70 Canada Osgoode Hall Law School (York University) Law WAM 70 - previous 2 yrs Chile La Pontificia Universidad Catholic de Chile All WAM 70 Chile Universidad Diego Portales All WAM 70 Chile Universidad de Chile All WAM 70 China Peking University All WAM 60 China Shanghai Jiao Tong University All WAM 60 China Sichuan University All WAM 60 China Tsinghua University All WAM 60 China Nanjing University All WAM 60 China Fudan University All WAM 60 China Harbin Institute of Technology All WAM 60 China Sun Yat-Sen University All WAM 60 China Univeristy of Science and Technology of China All WAM 60 China Xi'an Jiaotong University All WAM 60 China Zhejinag University All WAM 60 Colombia University of Antioquia All WAM 70 Denmark Copenhagen Business School -

QS World University Rankings® “Trusted by Students Since 2004”

QS World University Rankings® “Trusted by students since 2004” 2012 Report ) Welcome to the 2012/13 QS World University Rankings® Report he ninth annual QS World University As in previous years this information is TRankings arrive at a time of seismic counterbalanced by citations data sourced change in global higher education. from Scopus, the world’s most comprehensive database of research citations. The rankings also The boom in international study continues incorporate figures on student/faculty ratios to reconfigure the landscape, with well over and international students and faculty, collected 3.5 million students currently taking degrees and verified by a multilingual team of analysts abroad. The central importance of human working within QS Intelligence Unit. capital to 21st century economies is underlined by a global drive to expand the proportion of As the need for greater and more nuanced university graduates, while the competition information increases, QS has continued to to innovate through R&D intensifies every adapt. Rather than cramming a greater num- year. And as government budgets are squeezed ber of indicators into a single ranking table in the aftermath of the recession, in many – which in our view simply creates a mess – countries students and parents are being made since 2009 QS has introduced a series of more to contribute ever more to the cost of funding targeted exercises: QS University Rankings: this expansion. Asia; QS University Rankings: Latin America; QS World University Rankings by Subject; QS All of these changes and many more besides Best Student Cities; QS 50 Under 50; and QS mean that a reliable, trusted and rigorous Stars, a new, comprehensive university rating way of comparing universities worldwide has system. -

Welcoming a New Century • Focus on Hope • Seminarian Ministries

The Crossroads The Alumni Magazine for Theological College • Fall 2018 Welcoming a New Century • Focus on Hope • Seminarian Ministries Theological College | The National Seminary of The Catholic University of America A Letter from the Rector The Crossroads is published three times a year by the Office of Institutional Advance- ment of Theological College. It is distributed via non-profit mail to alumni, bishops, voca- S. SVL II PI tion directors, and friends of TC. R T A II N I W Rector M A E S Rev. Gerald D. McBrearity, P.S.S. (’73) S H I N M G Media & Promotions V L T L O I N Managing Editor G I S Suzanne Tanzi ✣ A Horizon of Hope Contributing Writers Jonathan Barahona • James Buttner Roger Schutz in his In order to prepare future priests who will be able to restore hope Liam Gallagher • Dr. Kathleen Galleher book, Living Today for and confidence amongst the people of God, Theological College is Rev. Matthew Gworek • Cornelia Hart Contents responsible for discerning the readiness of a priesthood candidate Alexandre Jiménez-Alcântara God, wrote, “During to enter the seminary and benefit from the formation program; Michael Kielor • Rev. Mark Morozowich the darkest periods of psychological tests and interviews, background checks, training Dr. John McCarthy • Justin Motes A Letter from the Rector ................................................................... 1 history, quite often a programs related to protecting the most vulnerable are all essential Mary Nauman • Jonathan Pham to the process of acceptance into Theological College. Once accept- Community News small number of men Michael Russo • Charles Silvas and women, scattered ed, every seminarian is accompanied by a spiritual director and a Cassidy Stinson Ordinations 2018 ........................................................................ -

Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration

Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final report Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway's Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final report © The Research Council of Norway 2014 The Research Council of Norway P.O.Box 2700 St. Hanshaugen N–0131 OSLO Telephone: +47 22 03 70 00 Telefax: +47 22 03 70 01 [email protected] www.rcn.no/english The report can be ordered at: www.forskningsradet.no/publikasjoner or green number telefax: +47 800 83 001 Design cover: Design et cetera AS Printing: 07 Gruppen/The Research Council of Norway Number of copies: 150 Oslo, March 2014 ISBN 978-82-12-03310-8 (print) ISBN 978-82-12-03311-5 (pdf) Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway’s Strategy for International Research Collaboration Final Report March 14, 2014 Authors Alexandre Beaudet David Campbell Grégoire Côté Stefanie Haustein Christian Lefebvre Guillaume Roberge Other contributors Philippe Deschamps Leroy Fife Isabelle Labrosse Rémi Lavoie Aurore Nicol Bastien St-Louis Lalonde Matthieu Voorons Contact information Grégoire Côté, Vice-President, Bibliometrics [email protected] Brussels | Montreal | Washington Bibliometric Study in Support of Norway’s Strategy for Final Report International Research Collaboration Contents Contents .................................................................................................................. i Tables ................................................................................................................... iii -

2017-18 Annual Report

Zoos Victoria Victoria Zoos Annual Report Annual Report 2017—18 Annual Report 2017—18 Big Wins and Brave Things Contents A year in review 5 Our charter and purpose 6 Governance and legislation 7 Action areas in focus 8 Conservation 9 Animals 10 Visitors and community 12 People 14 Financial sustainability 16 Environmental sustainability 17 Carbon emissions 17 Organisational chart 18 Our workplace profile 18 Key performance indicators 19 Financial summary 21 Board attendance 22 Board profiles 23 Board committees 26 Corporate governance and other disclosures 27 Our partners and supporters 34 Financial management compliance statement 38 Financial report 39 ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 3 In accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994, I am pleased to present Zoos Victoria’s Annual Report for the year ending 30 June 2018. Kate Vinot Dr. Jenny Gray Chair CEO Zoos Victoria Zoos Victoria 27th September 2018 ZOOS VICTORIA ZOOS 4 BIG WINS AND BRAVE THINGS A year in review Thousands of people enter the Zoos Victoria has changed its The opening of new exhibits remains gates of our three amazing zoos approach to conservation over the to be a highlight of Zoos Victoria’s every day, to see the animals they last five years. Through our research work. The effort invested into love and enjoy quality time with their and programs, we’ve realised the designing new animal facilities is family. Once inside, children squeal incredible power zoos have to considerable and demands a whole- with excitement and anticipation of significantly influence the success of-team approach. The new Kangaroo the marvels ahead as the rainbow and continuation of a species. -

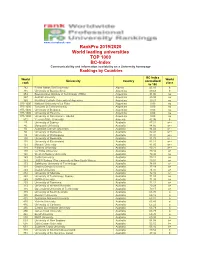

Rankpro 2019/2020 World Leading Universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and Information Availability on a University Homepage Rankings by Countries

www.cicerobook.com RankPro 2019/2020 World leading universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and information availability on a University homepage Rankings by Countries BC-Index World World University Country normalized rank class to 100 782 Ferhat Abbas Sétif University Algeria 45.16 b 715 University of Buenos Aires Argentina 49.68 b 953 Buenos Aires Institute of Technology (ITBA) Argentina 31.00 no 957 Austral University Argentina 29.38 no 969 Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina Argentina 20.21 no 975-1000 National University of La Plata Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 Torcuato Di Tella University Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Belgrano Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Palermo Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of San Andrés - UdeSA Argentina 0.00 no 812 Yerevan State University Armenia 42.96 b 27 University of Sydney Australia 87.31 a++ 46 Macquarie University Australia 84.66 a++ 56 Australian Catholic University Australia 84.02 a++ 80 University of Melbourne Australia 82.41 a++ 93 University of Wollongong Australia 81.97 a++ 100 University of Newcastle Australia 81.78 a++ 118 University of Queensland Australia 81.11 a++ 121 Monash University Australia 81.05 a++ 128 Flinders University Australia 80.21 a++ 140 La Trobe University Australia 79.42 a+ 140 Western Sydney University Australia 79.42 a+ 149 Curtin University Australia 79.11 a+ 149 UNSW Sydney (The University of New South Wales) Australia 79.01 a+ 173 Swinburne University of Technology Australia 78.03 a+ 191 Charles Darwin University Australia 77.19 -

Wake Forest College Faculty 1

Wake Forest College Faculty 1 Professor of Theatre WAKE FOREST COLLEGE BA, UNC-Chapel Hill; MFA, UNC-Greensboro. FACULTY Elizabeth Mazza Anthony (1998) Associate Teaching Professor of French Studies Date following name indicates year of appointment. Listings represent those BA, Duke University; MA, PhD, UNC-Chapel Hill. faculty teaching either full or part-time during the fall 2020 and/or spring Diana R. Arnett (2014) 2021. Associate Teaching Professor of Biology Irma V. Alarcón (2005) BS, MA, Youngstown State University; PhD, Kent State University. Associate Professor of Spanish and Italian Lisa Ashe (2016) BA, Universidad de Concepción (Chile); MA, PhD , Indiana University. Part-time Assistant Professor of Art Jane W. Albrecht (1987) BS, University of Tennessee; MA, PhD, University of Virginia. Professor of Spanish and Italian Miriam A. Ashley-Ross (1997) BA, Wright State University; MA, PhD , Indiana University. Professor of Biology Guillermo Alesandroni (2020) BS, Northern Arizona University; PhD, University of California (Irvine). Visiting Assistant Professor Robert J. Atchison (2010) BS, National University of Rosario; MS, University of Illinois at Chicago; Associate Professor of Communication and Director of Debate PhD, Oklahoma State University. BA, MA, Wake Forest University; PhD, University of Georgia. Rebecca W. Alexander (2000) Alison Atkins (2013) F.M. Kirby Family Faculty Fellow and Professor of Chemistry Assistant Teaching Professor of Spanish and Italian BS, Delaware; PhD, University of Pennsylvania. BA, Wake Forest University; MA, PhD , University of Virginia. Lucy Alfrd (2020) Emily A. Austin (2009) Assistant Professor of English Assistant Professor of Philosophy BA, University of Virginia; Phd, Stanford University; PhD, University of BA, Hendrix College; PhD, Washington University (St.