SPS Working Paper Template 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

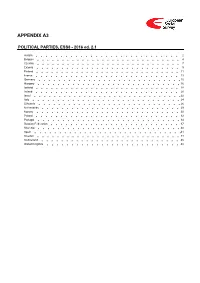

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Political Conflict, Social Inequality and Electoral Cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-2018

World Inequality Lab – Working Paper N° 2020/25 Political conflict, social inequality and electoral cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-2018 Attila Lindner Filip Novokmet Thomas Piketty Tomasz Zawisza November 2020 Political conflict, social inequality and electoral cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-20181 Attila Lindner, Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, Tomasz Zawisza Abstract This paper analyses the electoral cleavages in three Central European countries countries—the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland—since the fall of communism until today. In all three countries, the left has seen a prolonged decline in support. On the other hand, the “populist” parties increased their support and recently attained power in each country. We relate this to specific trajectories of post-communist transition. Former communist parties in Hungary and Poland transformed themselves into social- democratic parties. These parties' pro-market policies prevented them from establishing themselves predominantly among a lower-income electorate. Meanwhile, the liberal right in the Czech Republic and Poland became representative of both high-income and high-educated voters. This has opened up space for populist parties and influenced their character, assuming more ‘nativist’ outlook in Poland and Hungary and more ‘centrist’ in the Czech Republic. 1 We are grateful to Anna Becker for the outstanding research assistance, to Gábor Tóka for his help with obtaining survey data on Hungary and to Lukáš Linek for helping with obtaining the data of the 2017 Czech elections. We would also like to thank Ferenc Szűcs who provided invaluable insights. 1 1. Introduction The legacy of the communist regime and the rapid transition from a central planning economy to a market-based economy had a profound impact on the access to economic opportunities, challenged social identities and shaped party politics in all Central European countries. -

Politics in Central Europe

Politics in Central Europe The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association Volume 7 Number 2 December 2011 Regional Politics in Central Eastern Europe Next Issue: Cultural Transformation in Central Europe The articles published in this scientific review are placed also in SSOAR (Social Science Open Access Repository), http://www.ssoar.info CONTENTS ESSAYS Ladislav Cabada The Role of Central European Political Parties in the Establishment and Operation of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group . 5–18 Michaela Ježová Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Balkans . 19–37 Petr Jurek Possibilities for and Limitations of Regional Party Development in the Czech Republic and Slovakia . 38–56 Michal Kubát Reforming Local Governments in a New Democracy: Poland as a Case Study . 57–67 Přemysl Rosůlek Consolidation of the Centre-Right Political Camp in Hungary (1989–2002), Nationalism and Populism . 68–97 DISCUSSION Ladislav Jakl Regional European Integration of the Legal Protection of Industrial Property . 98–116. Tadeusz Siwek A Political-Geographic Map of Poland before the 2011 Election . 117–125. BOOK REVIEWS . 126–129 GUIDELINES FOR AUTHORS . 130–135 Politics in Central Europe 7 (December 2011) 2 ESSayS The Role of Central European Political Parties in the Establishment and Operation of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group1 Ladislav Cabada abstract: Central Eastern European political parties influenced and changed the ideological debate in the European parliament after the Eastern enlargement in 2004/2007 significantly. As the most influential ideological stream with a Central Eastern European “origin” or background we could observe the so-called Eurore- alist (or Eurogovernmentalist) political parties such as the Polish Right and Justice (PiS) or Czech Civic Democratic Party (ODS). -

Can We Do Better?

CAN WE DO BETTER? Grassroot parties’ success in maintaining their movement origins Comparative analysis of Podemos and Jobbik By Borbála Greskovics Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Zsolt Enyedi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Abstract This thesis aims to examine parties that criticize the traditional political system and traditional parties as well – whether or not they are able to do differently; or better from their perspective. I respond to this question by analyzing movement parties that typically aim to do something reformist compared to the parties that already exist. I analyze two parties in two different parts of Europe, with different historical backgrounds, both of which emerged from social movements, although with opposing ideologies. The leftist Podemos (‘We can’) in Spain and the radical right, Jobbik (‘Jobbik’) in Hungary, are both rooted in a movement and both claim that they can do better than the other parties that they believe have failed after the regime changes within their respective countries. This aim necessitates the exploration of empirical data that can be used to understand this complex phenomenon. Therefore, in this thesis, besides looking for an answer to the questions I also attempt to find those empirical materials that can be used to gain a deeper understanding of parties’ movement-like characteristics. The outcome of the thesis reveals certain characteristics of each party that might be connected to its movement origins. Podemos’ movement characteristics appear already in its operational structure, while Jobbik’s movement-like characteristics appear mainly in its informal relationship to its supporters. -

GUILTY NATION Or UNWILLING ALLY?

GUILTY NATION or UNWILLING ALLY? A short history of Hungary and the Danubian basin 1918-1939 By Joseph Varga Originally published in German as: Schuldige Nation oder VasalI wider Willen? Beitrage zur Zeitgeschichte Ungarns und des Donauraumes Teil 1918-1939 Published in Hungarian: Budapest, 1991 ISBN: 963 400 482 2 Veszprémi Nyomda Kft., Veszprém Translated into English and edited by: PETER CSERMELY © JOSEPH VARGA Prologue History is, first and foremost, a retelling of the past. It recounts events of former times, relates information about those events so that we may recognize the relationships between them. According to Aristoteles (Poetica, ch. IX), the historian differs from the poet only in that the former writes about events that have happened, while the latter of events that may yet happen. Modern history is mostly concerned with events of a political nature or those between countries, and on occasion with economic, social and cultural development. History must present the events in such a manner as to permit the still-living subjects to recognize them through their own memories, and permit the man of today to form an adequate picture of the events being recounted and their connections. Those persons who were mere objects in the events, or infrequently active participants, are barely able to depict objectively the events in which they participated. But is not the depiction of recent history subjective? Everyone recounts the events from their own perspective. A personal point of view does not, theoretically, exclude objectivity – only makes it relative. The measure of validity is the reliability of the narrator. The situation is entirely different with historical narratives that are written with a conscious intent to prove a point, or espouse certain interests. -

Codebook CPDS III 1990-2012

Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET III 1990-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for a group of 36 OECD and/or EU- member countries for the period 1990-20121. The data are primarily from the data set created at the University of Berne, Institute of Political Science and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation: The Comparative Political Data Set I (CPDS I). However, the present data set differs in several aspects from the CPDS I dataset. Compared to CPDS I Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus (Greek part), Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have been added. The present data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions is provided by Jelle Visser (2013). When using the data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. This data set is to be cited as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. 2014. Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2014-09-30 1 Data for former communist countries begin in 1990 for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Lativa and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. -

Government Composition, 1960-2018 Codebook

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2018 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2018 Klaus Armingeon, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel and David Weisstanner The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, David Weisstanner and Laura Knöpfel. 2020. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2018. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2020-08-20 1 Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2018 -

The State of Populism in Europe (2016)

2016 THE STATE OF POPULISM IN EUROPE Tamás BOROS Maria FREITAS Tibor KADLT Ernst STETTER The State of Populism in the European Union 2016 Published by: FEPS – Foundaton for European Progressive Studies Rue Montoyer, 40 – 1000 Brussels, Belgium www.feps-europe.eu Policy Solutons Square Ambiorix, 10 – 1000 Brussels, Belgium Revay utca, 10 – 1065 Budapest, Hungary www.policysolutons.eu Responsible editors: Ernst Steter, Tamás Boros Edited by: Maria Freitas Cover design: Ferling Ltd. – Hungary Page layout and printng: Ferling Ltd. – Hungary, Innovariant Ltd. Copyrights: FEPS, Policy Solutons ISSN: ISSN 2498-5147 This book is produced with the fnancial support of the European Parliament. Table of Contents Foreword 6 About Populism Tracker 8 Methodology 9 Overview: The most important trends in the support for populism in 2016 10 Countries with high support for populists 10 Most successful populist partes 14 Populists in government 18 Populist partes in EU Member States 21 Western Europe 21 Central and eastern Europe 24 Southern Europe 28 Northern Europe 31 Conclusion 34 Appendix I. Chronology: European populism in 2016 37 Appendix II. List of populist partes in the European Union 43 Foreword 2016 has been one of the most eventul years in European politcs since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Observers accustomed to predictable European afairs were shocked again and again by unexpected events: the refugee crisis – stll lingering from the previous year – and the social tensions surrounding it; the Britsh referendum on leaving the European Union (EU) and its striking outcome that shook the European project to its core with the unprecedented case of a Member State partng from the EU; the surprising results of German regional electons and the worrying trend of increasing popularity of right wing populists; the Hungarian plebiscite on the EU’s migrant quota, which added to refugee crisis tensions at the European level; and the Italian referendum on consttutonal reforms that turned into a protest vote against the country’s prime minister. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

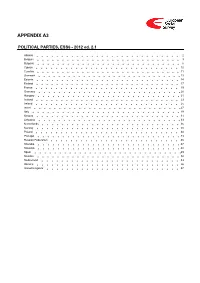

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2015a from May 22, 2015 Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset Version 2015a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the party’s or alliance’s name in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list by themselves. If the composition of an alliance changed between different elections, this change is covered as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party was a split from another party or a merger of a number of other parties and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 1.1 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. -

Populist Politics and Liberal Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

POPULIST POLITICS AND LIBERAL DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE Grigorij Mesežnikov, Oľga Gyárfášová, and Daniel Smilov Editors INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS 2 The authors and editors wish to thank Rumyana Kolarova, Lena Kolarska−Bobińska, Andras Sajo and Peter Učeň for reviewing the country studies and Kevin Deegan−Krause for proofreading. This publication appears thanks to the generous support of the Trust for Civil Society in Central & Eastern Europe 3 Edition WORKING PAPERS Populist Politics and Liberal Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe Grigorij Mesežnikov Oľga Gyárfášová Daniel Smilov Editors INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS Bratislava, 2008 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .....................................................................................................................................................................5 The Rise of Populism in Eastern Europe: Policy Paper .....................................................................................7 Daniel Smilov and Ivan Krastev CASE STUDIES: Bulgaria ................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Daniel Smilov Hungary ................................................................................................................................................................ 37 Renata Uitz Poland .................................................................................................................................................................. -

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government.