Coal Mining and Rural Livelihoods: Case of the Ib Valley Coalfield, Orissa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Land Use / Vegetation Cover Mapping of Ib Valley Coalfield Based on Satellite Data for the Year 2014

Report on Land Use / Vegetation Cover Mapping of Ib Valley Coalfield based on Satellite Data for the Year 2014 IB VALLEY COALFIELD Submitted to Mahanadi Coalfields Limited CMPDI Report on Land Use/ Vegetation Cover Mapping of Ib Valley Coalfield based on Satellite data for the year 2014 Submitted to Mahanadi Coalfields Limited Sambalpur March - 2015 Remote Sensing Cell Geomatics Division CMPDI (HQ), Ranchi Job No 561410027 Page i CMPDI Document Control Sheet (1) Job No. RSC-561410027 (2) Publication Date March 2015 (3) Number of Pages 28 (4) Number of Figures 07 (5) Number of Tables 06 (6) Number of Plates 02 (7) Number of Drawings 01 Land use/ Vegetation Cover mapping of Ib Valley (8) Title of the Report Coalfield using satellite data of the year 2014. Preparation of land use/vegetation cover map of Ib Valley (9) Aim of the Report Coalfield on 1:50,000 scale based on Landsat 8 (OLI) satellite data for creating the geo-environmental database. Remote Sensing Cell (10) Executing Unit Geomatics Division Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Ltd. Gondwana Place, Kanke Road, Ranchi (11) User Agency Mahanadi Coalfields Limited, Sambalpur Ms. A. Biswas, DyM(Geology) (12) Author Mr. N. P. Singh, GM(Geomatics) (13) Security Restriction Restricted Circulation (14) No. of Copies 6 (15) Distribution Statement Official Job No 561410027 Page ii CMPDI List of Figures 1. Map of India showing the location of Ib Valley Coalfield. 2. Remote Sensing Radiation System. 3. Electromagnetic Spectrum 4. Expanded Diagram of the visible and infrared regions. 5. Methodology of Land use/ Vegetation cover mapping. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 STATE POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD, ODISHA A/118, Nilakantha Nagar, Unit-Viii Bhubaneswar SPCB, Odisha (350 Copies) Published By: State Pollution Control Board, Odisha Bhubaneswar – 751012 Printed By: Semaphore Technologies Private Limited 3, Gokul Baral Street, 1st Floor Kolkata-700012, Ph. No.- +91 9836873211 Highlights of Activities Chapter-I 01 Introduction Chapter-II 05 Constitution of the State Board Chapter-III 07 Constitution of Committees Chapter-IV 12 Board Meeting Chapter-V 13 Activities Chapter-VI 136 Legal Matters Chapter-VII 137 Finance and Accounts Chapter-VIII 139 Other Important Activities Annexures - 170 (I) Organisational Chart (II) Rate Chart for Sampling & Analysis of 171 Env. Samples 181 (III) Staff Strength CONTENTS Annual Report 2018-19 Highlights of Activities of the State Pollution Control Board, Odisha he State Pollution Control Board (SPCB), Odisha was constituted in July, 1983 and was entrusted with the responsibility of implementing the Environmental Acts, particularly the TWater (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Cess Act, 1977, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 and the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. Several Rules addressing specific environmental problems like Hazardous Waste Management, Bio-Medical Waste Management, Solid Waste Management, E-Waste Management, Plastic Waste Management, Construction & Demolition Waste Management, Environmental Impact Assessment etc. have been brought out under the Environment (Protection) Act. The SPCB also executes and ensures proper implementation of the environmental policies of the Union and the State Government. The activities of the SPCB broadly cover the following: Planning comprehensive programs towards prevention, control or abatement of pollution and enforcing the environmental laws. -

Inner Front.Pmd

BUREAU’S HIGHER SECONDARY (+2) GEOLOGY (PART-II) (Approved by The Council of Higher Secondary Education, Odisha, Bhubaneswar) BOARD OF WRITERS (SECOND EDITION) Dr. Ghanashyam Lenka Dr. Shreerup Goswami Prof. of Geology (Retd.) Professor of Geology Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar, Burla Dr. Hrushikesh Sahoo Dr. Sudhir Kumar Dash Emeritus Professor of Geology Reader in Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Sundargarh Autonomous College, Sundargarh Dr. Rabindra Nath Hota Dr. Nabakishore Sahoo Professor of Geology Reader in Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur Dr. Manoj Kumar Pattanaik Lecturer in Geology Khallikote Autonomous College, Berhampur BOARD OF WRITERS (FIRST EDITION) Dr. Satyananda Acharya Mr. Premananda Ray Prof. of Geology (Retd.) Reader in Geology (Retd.) Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Mr. Anil Kumar Paul Dr. Hrushikesh Sahoo Reader in Geology (Retd.) Professor of Geology Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Dr. Rabindra Nath Hota Reader in Geology, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar REVIEWER Dr. Satyananda Acharya Professor of Geology (Retd) Former Vice Chancellor of Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Published by THE ODISHA STATE BUREAU OF TEXTBOOK PREPARATION AND PRODUCTION Pustak Bhawan, Bhubaneswar Published by: The Odisha State Bureau of Textbook Preparation and Production, Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India First Edition - 2011 / 1000 Copies Second Edition - 2017 / 2000 Copies Publication No. - 194 ISBN - 978-81-8005-382-5 @ All rights reserved by the Odisha State Bureau of Textbook Preparation and Production, Pustak Bhavan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission from the Publisher. -

How Coal Mining Is Trashing Tigerland

Author Contact Ashish Fernandes Ashish Fernandes [email protected] Research coordination & North Karanpura case study Nandikesh Sivalingam Kanchi Kohli [email protected] Research Photo Editor Aishwarya Madineni, Vikal Samdariya, Arundhati Sudhanshu Malhotra Muthu and Preethi Herman Design GIS Analysis Aditi Bahri Ecoinformatics Lab, ATREE (Kiran M.C., Madhura Cover image Niphadkar, Aneesh A., Pranita Sambhus) © Harshad Barve / Greenpeace Acknowledgments Image Sudiep Shrivastava for detailed inputs on the Forests of Sanjay Dubri Tiger Hasdeo-Arand and Mandraigarh sections, Kishor Reserve near Singrauli coalfield Rithe for inputs on the Wardha and Kamptee © Dhritiman Mukherjee / Greenpeace sections, Bulu Imam and Justin Imam for their expertise on the North Karanpura section, Biswajit Printed on 100% recycled paper. Mohanty for feedback on the Talcher and Ib Valley sections and Belinda Wright for feedback on the Sohagpur and Singrauli sections. CONTENTS Executive Summary 01 9. Hasdeo-Arand (Chhattisgarh) 51 10. West Bokaro (Jharkhand) 55 Introduction 09 Central India,Tigers, Corridors and Coal 11. North Karanpura (Jharkhand) 60 How Coal is Trashing Tigerland 17 Case Study I 63 The North Karanpura Valley - On the edge Methodology 21 12. Wardha (Maharashtra) 00 Coalfield Analysis 25 13. Kamptee (Maharashtra) 00 1. Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 27 Case Study II 87 2. Sohagpur (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 33 Chandrapur’s tigers - Encircled by coal 3. Sonhat (Chhattisgarh) 35 4. Tatapani (Chhattisgarh) 37 Alternatives: Efficiency and Renewables 101 5. Auranga (Jharkhand) 39 References 109 6. Talcher (Odisha) 41 Glossary 7. Ib Valley (Odisha) 47 110 8. Mandraigarh (Chhattisgarh) 49 Endnotes 111 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As India’s national animal, the Royal Bengal Tiger Panthera tigris has ostensibly been a conservation priority for current and past governments. -

(INDIAN SCHOOL of MINES), DHANBAD Phd Degrees Awarded by the Institute Since 1969 (After Declaration of the Status of Deemed University in 1967) Sl

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (INDIAN SCHOOL OF MINES), DHANBAD PhD Degrees Awarded by the Institute since 1969 (after declaration of the status of Deemed University in 1967) Sl. Date of Department/ Name of the candidate Guide(s) Title of the thesis No Award Discipline TECTONIC ANALYSIS OF A PART OF FOLDED BAIJNATH NAPPE AND 1 Shrish 24-03-1969 Applied Geology Prof S. N. Sarkar KROL BELT IN BAIJNATH-KAUSHANI-SOMESHWAR AREA, U.P. STRUCTURAL, METAMORPHIC AND GRANITIZATION HISTORY OF A 2 Shantimoy Dutta 17-06-1969 Applied Geology Prof. S. N. Sarkar PART OF FOLDED GARHWALI NAPPE AROUND LANSDOWNE, U.P. 3 Kaulir Kishore Chatterjee 29-12-1969 Applied Geology Prof D Chandra PETROLOGY OF BALL COALS OF INDIA PALAEOMAGNETISM OF THE KAMTHI AND PARSORE RED 4 M S Bhalla 21-09-1971 Applied Geophysics Prof J Singh SANDSTONES FROM INDIA SOME STUDIES IN EXPLORATION OF GROUND WATER WITH SPECIAL 5 Amiya Kumar Sen 13-07-1972 Applied Geophysics Prof J Singh REFERENCE TO GEOELECTRICAL SOUNDINGS & ELECTRICAL PROPERTIES OF ROCKS Prof. J Singh & H K Gupta, STUDY OF RESERVOIR-ASSOCIATED SEISMIC ACTIVITIES AND 6 B K Rastogi 18-09-1972 Applied Geophysics NGRI MULTIPLE EARTH QUAKES A REGIONAL PETROLOGIC STUDY OF LOWER GONDWANA FORMATIONS IN PENCH-KANHAN VALLEY COALFIELD OF MADHYA 7 Kishan Lal Rai 21-04-1973 Applied Geology Dr R T Shukla PRADESH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO BARAKAR MEASURES (INCLUDING COAL) Prof. J Singh & J G Negi, 8 S C Garde 22-06-1973 Applied Geophysics STUDIES ON REDUCTION AND INTERPRETATION OF GRAVITY DATA NGRI STRUCTURE & METAMORPHISM OF SINGHBHUM GROUP OF ROCKS 9 Anirudha Basu 25-03-1974 Applied Geology Prof S. -

Form-I/Mcl/2017-18/Feb-18/58/01

CMPDI/FORM-I/MCL/2017-18/FEB-18/58/01 Form-I Application for Prior Environmental Clearance for Coal Mining Project of SIARMAL OPEN CAST PROJECT Mining Lease Area (in Ha) Capacity (MTY) 2290.45 50.0 BASUNDHARA AREA IB VALLEY COALFIELD MAHANADI COALFIELDS LIMITED February 2018 Prepared by REGIONAL INSTITUTE – VII CENTRAL MINE PLANNING & DESIGN INSTITUTE LIMITED (A Subsidiary of Coal India Limited) BHUBANESWAR-751013, ODISHA. Accreditation Number: NABET/EIA/01/12/002 Dt. Jan 31, 2012. CMPDI Application for Prior Environmental Clearance (EC) (Increase in Production Capacity) FORM 1 [As per MoEF, Notification dtd.14th September 2006 With subsequent amendment vide notification dt.01.12.2009] (I) Basic Information Sl. Item Details No. 1 Name of the Project/s Siarmal Opencast Project 2 S. No. in the schedule 1 (a) 3 Proposed capacity/ area/ length/ Proposed Capacity 50.0 Mty tonnage to be handled/ command Mining lease area : 2290.45 Ha area/ lease area/ number of wells Total area requirement : 2580.45 Ha to be drilled 4 New/ Expansion/ Modernization New 5 Existing Capacity/ Area etc. NA 6 Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ A 7 Does it attract the general No condition? If yes, please specify. 8 Does it attract the specific NA condition? If yes, please specify. 9 Location IB valley Coalfields, Odisha Village(s) Siarmal, Jhupurunga, Tumlia, Ratansara, Gopalpur and Kulda. Tehsil Himgir District Sundergarh State Odisha 10 Nearest railway station/ airport Himgir station : 35 km along with distance in Kms. Jharsuguda Airport : 75 km 11 Nearest Town, city, District Himgir – 35 km Job No.706124 Form-I, Page - 1 CMPDI Sl. -

Mine Water Utilization Status Report – Format Circulated to Coal Companies by Moc

Ministry of Coal Sustainable Development Cell Status Report on Mine Water Utilization June, 2021 PREFACE Coal plays a crucial role in India’s energy consumption matrix and is expected to remain the bedrock of the energy supply for the country till 2030 and beyond. Coal India Limited (CIL), NLC India Limited (NLCIL) and Singareni Collieries Company Limited (SCCL) are key contributors towards coal production in India and have set ambitious targets to push up coal production in the coming years. Apart from coal production, emphasis is also placed on facilitating improvement in social and environmental scenario of coal mining areas through various forums / mechanisms; utilization of mine water is a stepping stone towards fulfilling this agenda. Mine water generation occurs where aquifers surrounding the coal seams get exposed during the mining operation – the result is an accumulation of groundwater in a sump within the mine. In order to continue safe mining operations, the accumulated mine water is dewatered to a separate sump within the mine lease area. Generally, these mine water sumps / pit lakes are retained even post closure of the mines and provide an excellent opportunity for storage of freshwater. Such accumulated mine water lakes are usually free from pollutants and can be utilized as a source of water with an aim towards enhancing environmental responsibility by coal producing companies. Mine water can be utilized for the following broad purposes: for industrial and domestic purposes within the mining project, for community uses -

Coal Mines and Related Activities Versus Environment in Orissa

August - October ‘05 Vol-2 No-1 The countrys industrial heritage was built upon indigenous coal. India ranks 3rd among the coal producing countries in the world which fulfills 63%. of the countrys energy need. It is expected that coal production in India will soon double. Orissa shares 24.60%. of the countrys reserves covering an area of 18482.857 ha in 26 mines located in Talcher & Ib valley area. Although coal supplies the bulk of energy needs, its mining and usage cause environmental damage, such as air pollution, noise pollution, land degradation and water pollution. Coal Mines and Related activities Versus Environment in Orissa Coal is the most important and abundant fossil fuel Table - I in India. It accounts for 63% of the country’s energy Coal Reserves in Million Tonnes need. India now ranks 3rd among the coal producing Proved Probable Inferred Total countries. Most of the coal production in India comes India 84414 98546 38023 220983 from open pit mines contributing over 80% of the Orissa 11308 23729 23729 51571 total production. 247.85 billion tonnes of coal reserves As per 2001 estimate. are estimated by the GSI (as on 1.1.2005), out of Table - II which Orissa accounts for 60.98billion tonnes (24.60%). This is next to Jharkhand, which accounts Distribution of Coal mines for 72.20 billion tonnes (29.13%) of total coal reserve. Open Under Mixed Total cast ground The major coal mines are located in Talcher and Ib India 147 366 48 561 valley in orissa. Although coal plays an important Orissa 12 14 0 26 role in catering to energy needs, it also causes [ Talcher & environmental damage during mining, IbValley] transportation and processing. -

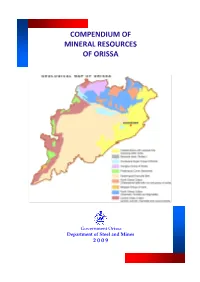

Compendium of Mineral Resources of Orissa

COMPENDIUM OF MINERAL RESOURCES OF ORISSA Government Orissa Department of Steel and Mines 2 0 0 9 Compendium of Mineral Resources of Orissa Orissa, situated on the eastern seaboard of India is one of the gifted parts of the World, where a gamut of mineral resources exist in bounty. The state is endowed with large reserves of bauxite, chinaclay, chromite, coal, dolomite, fireclay, graphite, gemstones, iron ore, limestone, manganese ore, mineral sand, nickel ore, pyrophylite and quartz. Recent discovery of diamond in the Dharambandha area of Nuapada district by the State Directorate of Geology has added a coloured feather in the cap of the state. Other minerals of the state include copper ore, lead ore, titanium bearing vanadiferous magnetite, talc/ soap stone and high magnesia igneous rocks. Recent boom of the mineral industry has turned the state in to a hotspot, with entrepreneurs from all over the World crowding the state for their share of fortune. The rich mineral wealth of the state is attributed to its favourable Geological setup. Situated on the eastern fringe of the peninsular India, Orissa has about 72.5%of the area occupied by Precambrian metamorphic rocks (of Archaean and Proterozoic age) which hosts the majority of the minerals. The Gondwanas hosting the coal resources occur over about 8% of the landmass. The tertiary and quaternary formations, occupying rest of the area, provide avenues for aluminous/ nickeliferous laterite and heavy minerals (in beach sand). The Archaean rocks in northern Orissa include the Supracrustal belts of metasedimentary rocks including Iron Ore Super Group having deposits of iron, manganese, gold and basemetals. -

Geotechnical Investigation of Coal Mine Refuse for Backfilling in Mines

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ethesis@nitr GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF COAL MINE REFUSE FOR BACKFILLING IN MINES A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY IN MINING ENGINEERING BY VISHAL KUMAR AGARWAL DEPARTMENT OF MINING ENGINEERING NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROURKELA – 769 008 2009 GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION OF COAL MINE REFUSE FOR BACKFILLING IN MINES A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY IN MINING ENGINEERING BY VISHAL KUMAR AGARWAL Under the Guidance of Dr. H. B. Sahu DEPARTMENT OF MINING ENGINEERING NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROURKELA – 769 008 2009 National Institute of Technology Rourkela C E R T I F I C A T E This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Geotechnical Investigation of Coal Mine Refuse for Backfilling in Mines” submitted by Sri Vishal Kumar Agarwal in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Bachelor of Technology degree in Mining Engineering at the National Institute of Technology, Rourkela is an authentic work carried out by him under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge, the matter embodied in the thesis has not been submitted to any other University/Institute for the award of any Degree or Diploma. Date: Dr H. B. Sahu Dept. of Mining Engineering National Institute of Technology Rourkela,769008 (i) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I record my sincere gratitude to Dr. H. B. Sahu, Assistant Professor, Department of Mining Engineering for assigning me the project “Geotechnical Investigation of Coal Mining Waste”. -

Meeting of E Standing Committee on Safety in Coal

AGENDA FOR 42ND MEETING OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SAFETY IN COAL MINES On 26 TH FEBRUARY, 2018 AT NEW DELHI GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COAL 1 | P a g e 42ND MEETING OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SAFETY IN COAL MINES INDEX Agenda Page Agenda Items Sl. No. Nos. I In Memoriam. 3-5 Confirmation of the minutes of the 41 st meeting of II 6-11 Standing Committee on Safety in Coal Mines. Action Taken Report on the recommendations of the III 41 st meeting of Standing Committee on Safety in Coal 12-31 Mines held on 21.12.2016. IV Accident Statistics for last three years 32-57 Accident comparison between 41 th & 42 st Standing V 58-59 Committee Meeting. Analysis of Major Accidents that occurred during last VI 60-65 one year. VII Risk Assissment and Management 66-71 VIII Rationalization of Statutory Manpower 72-75 IX Safety Budget and its utilization 76-77 IX Occupational Health Hazards and Health Risk 78-82 X Any other matter with permission of the Chair. 83 2 | P a g e AGENDA ITEM NO. I In Memoriam In memory of all those who laid down their lives in furtherance of coal mining in the country since last meeting of the Standing Committee . ***** STANDING COMMITTEE ON SAFETY IN COAL MINES DEEPLY MOURNS THE SAD DEMISE OF THE FOLLOWING EMPLOYEES AND PAY HOMAGE TO ALL THOSE WHO SACRIFICED THEIR PRECIOUS LIVES FOR THE CAUSE OF THE NATION DURING THE PERIOD BETWEEN 41 ST & 42 ND MEETING OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON SAFETY IN COAL MINES. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 16473-IN STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized INDIA COAL SECTOR REHABILITATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized July 31, 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized Energy Sector Unit South Asia Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of June 30, 1997) Currency units = Rupees (Rs) One Rupee = US$ 0.03 (approx.) One US Dollar (US$) = Rs35.8 One US Dollar (US$) = SDR 0.72 MEASURES AND EQUIVALENTS 1 metric ton of (Indian) coal 0.46 metric tons of oil 1.9 metric tons of lignite 570 cubic meters of natural gas 1.0 metric ton of firewood 2.0 metric tons of animal dung ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BCCL - Bharat Coking Coal Limited CCL - Central Coalfields Limited CIL - Coal India Limited CMPDI - Central Mine Planning and Design Institute CPRA - Coal Price Regulation Account CSRP - Coal Sector Rehabilitation Project ECL - Eastern Coalfields Limited ESMP - Environmental and Social Mitigation Project GOI - Government of India MCL - Mahanadi Coalfields Limited Mt. - Million tons MW - Megawatt NCL - Northern Coalfields Limited PAPs - Project-affected people SAIL - Steel Authority of India Limited SEB - State Electricity Board SECL - South Eastern Coalfields Limited tce - tons of coal equivalent (6,000 kcal/kg) toe - tons of oil equivalent WCL - Western Coalfields Limited FISCAL YEAR April 1 through March 31 Vice President: Mieko Nishimizu Country Director: Edwin Lim Sector Unit Manager: Alastair McKechnie Task Manager: Hiroaki Suzuki INDIA COAL SECTOR REHABILITATION PROJECT LOAN /CREDIT ANDPROJECT SUMMARY Borrower: India, acting by its President (IDA Credit) and Coal India Ltd. (IBRD Loan) Implementing Agencies: Government of India (The Ministry of Coal), Coal India Ltd., Central Coalfields Ltd., Mahanadi Coalfields Ltd., Northern Coalfields Ltd., South Eastern Coalfields Ltd., and Western Coalfields Ltd.