Route 36 Ohio to Colorado—America's Heartland Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003

For Lease Retail/Office Space 590 National Road, Wheeling, WV 26003 Property Information � 15,000 SF of retail/office space available | Can be subdivided to 7,000 SF � Former corporate headquarters with custom finished board room and multiple executive offices � Potential build-to-suit - 8,000 SF of office/retail space � Local loan/incentive packages available for relocations � Well maintained commercial space � Elevator served � Signage opportunity on National Road � Over 50 on-site parking spaces � Located in the heart of the Marcellus and Utica Gas Shale region � Close Proximity to US Route 40, Interstate 70, Interstate 470,West Virginia Route 2 & West Virginia Route 88 For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Century Centre � 1233 Main Street, Suite 1500 � Wheeling, WV 26003 960 Penn Avenue, Suite 1001 � Pittsburgh, PA 15222 304.232.5411 � www.century-realty.com SITE I-70 On Ramp 8,000 Vehicles/Day I-70 47,000 Vehicles/Day Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. All property information should be confirmed before any completed transaction. For More Information, Please Contact: Adam Weidner John Aderholt, Broker [email protected] [email protected] 304.232.5411 304.232.5411 Expansion Space or Drive Thru Potential Drive Thru 8,000 SF Wheeling The 30 Miles to Highlands Washington, PA Pittsburgh Approximately Wheeling 38 Miles Columbus Approximately 136 Miles Ownership has provided the property information to the best of its knowledge, but Century Realty does not guarantee that all information is accurate. -

F-4-100 Braddock Monument

F-4-100 Braddock Monument Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 01-31-2013 MARYLAND HISTORICAL TRUST NR Eligible: yes DETERMINATION OF ELIGIBILITY FORM no kopertyName: Braddock Monument Inventory Number: F-4-100 Address: South side ofU.S. 40 Alternate Historic district: yes X no City: Braddock Heights, MD Zip Code: County: Frederick USGS Quadrangle(s): Frederick Property Owner: Daughters of the American Revolution, Frederick Chapter Tax Account ID Number: Tax Map Parcel Number(s): Tax Map Number: Project: Monument relocation Agency: MD SHA Agency Prepared By: MD SHA Preparer's Name: Anne E. Bruder, Architectural Historian Date Prepared: 04/07/2009 Documentation is presented in: Project Review and Compliance files. -

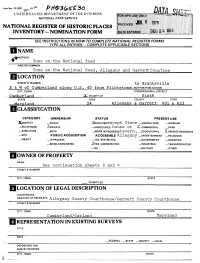

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

:orm No. 10-300 ^0'' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME •^HISTORIC Inns on the National Road AND/OR COMMON Inns on the National Road, Allegany and GarrettCounties LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER to Grantsville & W of Cumberland, a^ong U.S. 40 from Flintstone-NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT .Cumberland Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 24 Alleaanv & Garrett 001 & 023 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE XDISTRICT —PUBLIC —XoccupiEDexcept Stone _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _=j8UILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED house or X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _woRKiNpROGRESstavern, —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE Allegany —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME See continuation sheets 3 and STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Allegany County Courthouse/Garrett County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Maryland 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGrNAL SITE GOOD XRUINS only Stone ALTERED MOVED r»ATF *A.R _ UNEXPOSED house or tavern, Allegany DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Eleyen of the inns that served the National Road and the Baltimore Pike in Allegany and Sarrett Counties, Maryland, during the 19th century re main today. ALLEGANY COUNTY The Flints tone Hot e 1 stands on the north side of old Route 10 to the east of Hurleys Branch Road in Flintstone. -

Western Pennsylvania History Spring 2016

Up Front This advertisement informs travelers about passage on the National Road Stage Company’s line of coaches. The Reporter, July 22, 1843. sheep, and pigs from western farms to the Meadowcroft markets of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Wagoners could transport salt, sugar, tea, By Mark Kelly coffee, and iron to western settlements, then Meadowcroft Interpreter/Tour Guide return with whiskey, wool, flour, and bacon much more efficiently in their Conestoga wagons.3 Even though this improved route Carried in Comfortable Coaches made the journey easier for many, the pace Hagerstown, Maryland. An ad in Washington, of travel was still only a few miles an hour. Pa.’s The Reporter on April 30, 1821, states,“The In 1806, Thomas Jefferson signed “An Act to For those who could afford it, stage coaches arrangement of this line, will secure a Regulate the Laying Out and Making a Road offered speedy travel between cities in the East passenger a safe conveyance from Wheeling to from Cumberland in the State of Maryland, to and the Midwest. Philadelphia (a distance of 346 miles) in a little the State of Ohio.”1 This road would ease the The earliest stage lines spanned the more than four days.”6 The pair continued to journey of settlers moving west by improving 131-mile-trip from Cumberland to Wheeling expand their operations west, establishing the part of the existing road cut by British in four different sections, but ran only three National Road Stage Company in Uniontown General Edward Braddock in 1755, and link times each week.4 These original lines, bought around 1824. -

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926

National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926 Library of Congress The National Road, in many places now known as Route 40, was built between 1811 and 1834 to reach 1910 photo of the National Road, the western settlements. It was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. George Washington and 1.5 miles west Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary for unifying the young country. of Brownsville, In 1806, Congress authorized construction of the road, and President Jefferson signed the act establish- Pennsylvania. ing the National Road. In 1811, the first contract was awarded, and the first 10 miles of road were built. As work on the road progressed, a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages are still found along the National Road. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike, and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning it the nickname “The Main Street of America.” In the 1800s, it was a key transport path to the West for thousands of settlers. In 1912, the road became part of the National Old Trails Road, and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926, the road became part of U.S. 40 as a coast-to-coast highway running from Atlantic City to San Francisco. Contributions & Crossroads Our National Road System’s Impact on the U.S. Economy and Way of Life National Road/Route 40 1811-1834, 1926 Public domain photo by Lyle Kruger A section of Route 40 (above) with its original paving bricks stretches out to the horizon. -

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri the Statue Is a Tribute to the Many Hundreds of Thousands of Women Who Took Part In

Madonna of the Trail Lexington, Missouri The statue is a tribute to the many hundreds of thousands of women who took part in the Western United States Migration. Madonna of the Trail is a series of 12 identical monuments dedicated to the sprit of pioneer women in the United States. In the late 1920’s, the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) commissioned the design, casting and placement of twelve memorials commemorating the spirit of pioneer women. These monuments were installed in each of 12 states along the National Old Trails Road, which extended from Cumberland, Maryland, to Upland, California. The Madonna of the Trail is depicted as a courageous pioneer woman, clasping her baby with her left arm while clutching her rifle in her right, wearing a long dress and bonnet. Her young son clings to her skirts. On Monday, September 17, 1928, The Missouri Madonna of the Trail in Lexington, Missouri, was unveiled and dedicated. Harry S. Truman, a Missouri Justice of the Peace and the President of the National Old Trails Association, was the keynote speaker at the ceremony. The ceremony was in many ways a “home-coming” for Lexington, and the streets were crowded with visitors while homes were filled with guests. Most of the visitors were former residents, relatives, and people with connections with Lexington. Many people dressed in period costume, including some eighty-plus year old “real pioneer women” who were dressed in costumes that were over 100 years old. On August 25, 1928, prior to the dedication, a copper box time capsule, filled with pictures, books, pamphlets and other miscellaneous items, was deposited in the base of the pioneer mother statue. -

The National Road

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Necessity National Battlefield The National Road piznnsgivania ^ Illinois 0) Mount ashlngton Tavern Indiana ^ A \ W Va. (\?irginia KizntueRu till National Road, built by federal funds,600 mnes Baltimore Pike, buit by private funds Virginia Missouri Proposed but not constructed The National Road, designated U.S. Route 40 in 1925, was the first highway built entirely with federal funds. The road was authorized by Congress in 1806 during the Jefferson Administration. Construction began in Cumberland, Maryland in 1811. The route closely paralleled the military road opened by George Washington and General Braddock in 1754-55. S By 1818,the road had been completed to the Ohio River at Wheeling, which was then in Virginia. Eventually the road was pushed through central Ohio and Indiana, reaching Vandalia,Illinois in the 1830s where construction ceased due to a lack offunds. The National Road opened the Ohio River Valley and the Midwest for settlement and commerce. Traveling The opening of the road saw thousands of travelers Taverns were probably the heading west over the Allegheny Mountains to most important and numerous businesses found on settle the rich land of the Ohio River Valley. Small the National Road. It is estimated there was about towns along the National Road's path began to one tavern every mile on the National Road. There grow and prosper with the increase in population. were two different classes of taverns on the road. Towns such as Cumberland, Uniontown, The stagecoach tavern was one type. It was the Brownsville, Washington,and Wheeling evolved more expensive accommodation, designed for the into commercial centers of business and industry. -

THE NATIONAL ROAD the Road to Allegany and Garrett County History

42 m o u n t a i n d i s c o v e r i e s THE NATIONAL ROAD The Road to Allegany and Garrett County History Written by: Dan Whetzel Photography by: Lance C. Bell Western Maryland received a major economic As military operations of the French and Indian and boost in 1806, and secured a place in American history, Revolutionary Wars subsided, the young nation directed when Cumberland was selected as the starting point for its attention to economic enterprises. Calls for improved the National Road, America’s first federally funded highway roads were issued by commercial interests and land speculators that eventually stretched from Cumberland, Maryland who realized the monetary rewards of accessing natural to Vandalia, Illinois. The road was also called The National resources in western territories. Manufactured goods moving Turnpike and Cumberland Road. Several general reasons westward benefited the settlers who also sought access to favored construction of the road in Maryland, including eastern markets for their crops and raw materials. Before geography, land speculation, and economic pressures from roads, all commerce between the interior and the east coast western settlers. Cumberland was also a logical choice for had to be by a water route down the Ohio and Mississippi the new highway as it was already connected to the port Rivers, through the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, and city of Baltimore by an existing road, commonly called the then up the coast. Mutually beneficial interests caused Cumberland Road, and because British General Edward a consensus to be formed regarding the need for better Braddock used it as a base of operation in his highly pub- roads, but the funds to finance them remained elusive. -

The Indiana Byway Program

The Indiana Byway Program The Indiana Byway Program has been provides professional support to the in existence since about 1997 and is local byway leaders. designed to preserve, protect, enhance and recognize transportation corridors of The Ohio River Scenic Byway unique character. These corridors are notable examples of our nation's beauty, history, culture and recreational experience. Featured highways were designated nationally by the U.S. Secretary of Transportation in 1996, 1998, 2000 and 2002 from nominations presented by the states. INDOT is responsible for submitting Indiana route nominations for national designation and for submitting projects for discretionary grant funding. More than just scenic highways byways possess the outstanding qualities that exemplify the diverse regional character of our nation. Because Indiana wants byway designation to mean more than identification by a sign, the Indiana The Ohio River Scenic Byway (ORSB) Program emphasizes the same intrinsic is a 302-mile route that roughly parallels qualities used under the federal the famous river so important to the program. Indiana has been recognized early settlement of the continental as a leader among multi-state byways. United States. Most of the route follows state roads, but some sections fall under Indiana has two nationally-designated local jurisdiction. The ORSB extends byways and one state byway. All began across 13 southern Indiana counties. In as multi-county initiatives in towns 1998 the Ohio and Illinois portions of the representing a range of resources, byway joined the Indiana section to form socioeconomic and geographic a 967-mile National Scenic Byway. diversity. Each was initially designated a state byway. -

Wheeling and Pittsburgh in the Nineteenth Century

Urban Rivalry in the Upper Ohio Valley: Wheeling and Pittsburgh in the Nineteenth Century HE HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF URBAN COMPETITION for trade and commerce has frequently focused on such important eastern Tcities as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York. These urban giants established their preeminence in America's colonial era, but continued to bicker as new forms of transportation, first the canal, then the railroad, offered economic advantages to the city that secured new improvements. Yet at the turn of the nineteenth century new cities in the West were just beginning their struggle for urban hegemony, and their rivalries took on a different cast as the cities grew up with the market revolution and the transportation technologies that became vivid signals for a growing nation. Western urban growth was tied to trade and the initial agent of that commercial development was the Ohio River. Flowing west from its origins at Pittsburgh, the Ohio River fueled the growth of that city and sparked a secondary round of urban competition with downstream rivals at Cincinnati and Louisville. In his classic study of urban development, historian Richard Wade noted that "before a city could hope to enter the urban sweepstake for the largest prize, it had to eliminate whatever rivals arose in its own area." In some local regions the battle was uneven and the weaker town was quickly eliminated. Louisville annexed nearby Shippingsport and Portland to eliminate their competition. Pittsburgh had similar motives in moving to annex Allegheny. Farther west, the rapid growth of St. Louis quickly dashed the THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. -

West Mojave Route Management Plan, Historic Properties Treatment Plan, Attachment 5: Historic Trails Context Study FINAL VERSION May 2019

West Mojave Route Management Plan, Historic Properties Treatment Plan, Attachment 5: Historic Trails Context Study FINAL VERSION May 2019 Prepared for: United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de Los Lagos Moreno Valley, California 92553 Prepared by: Diane L. Winslow, M.A., RPA, Shannon Davis, M.A., RPH, Sherri Andrews, M.A., RPA, Marilyn Novell, M.S., and Lindsey E. Daub, M.A., RPA 2480 N. Decatur Blvd., Suite 125 Las Vegas, NV 89108 (702) 534-0375 ASM Project Number 29070 West Mojave Route Management Plan, Historic Properties Treatment Plan, Attachment 5: Historic Trails Context Study Prepared for: United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de Los Lagos Moreno Valley, California 92553 Prepared by: Diane L. Winslow, M.A., RPA, Shannon Davis, M.A., RPH, Sherri Andrews, M.A., RPA, Marilyn Novell, M.S., and Lindsey E. Daub, M.A., RPA ASM Affiliates, Inc. 2480 North Decatur Boulevard, Suite 125 Las Vegas, Nevada 89108 May 2019 PN 29070 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page MANAGEMENT SUMMARY ................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 2. LITERATURE REGARDING TRAILS, ROADS, AND HIGHWAYS ............... 7 3. DEFINING TRAILS, ROADS, AND HIGHWAYS ........................................... 9 4. PREHISTORIC, PROTO-HISTORIC, AND